New Delhi: India is spending billions to modernise its courts. New halls are rising. Documents are being turned into PDF files, and video links connect courtrooms to jails across the country.

The transformation is real. But, in practice, 5.4 crore cases remain stuck in the system.

Data placed before Parliament during the 2026 Budget session by Union Law and Justice Minister Arjun Ram Meghwal reveals a structural fault line at the heart of India’s judicial reform effort—the state is building the scaffolding for faster justice without filling the benches that would deliver it.

Also Read: 198 in UP, 160 in Bengal: HCs begin reporting data for pending acid attack cases sought by SC

The infrastructure push

The numbers on physical and digital expansion are substantial.

The eCourts Mission Mode Project, launched to digitise the system at district courts across the country, is now in Phase III (2023–2027). This stage of the project has an outlay of Rs 7,210 crore, more than four times the Rs 1,670 crore utilised in Phase II (2015–2023).

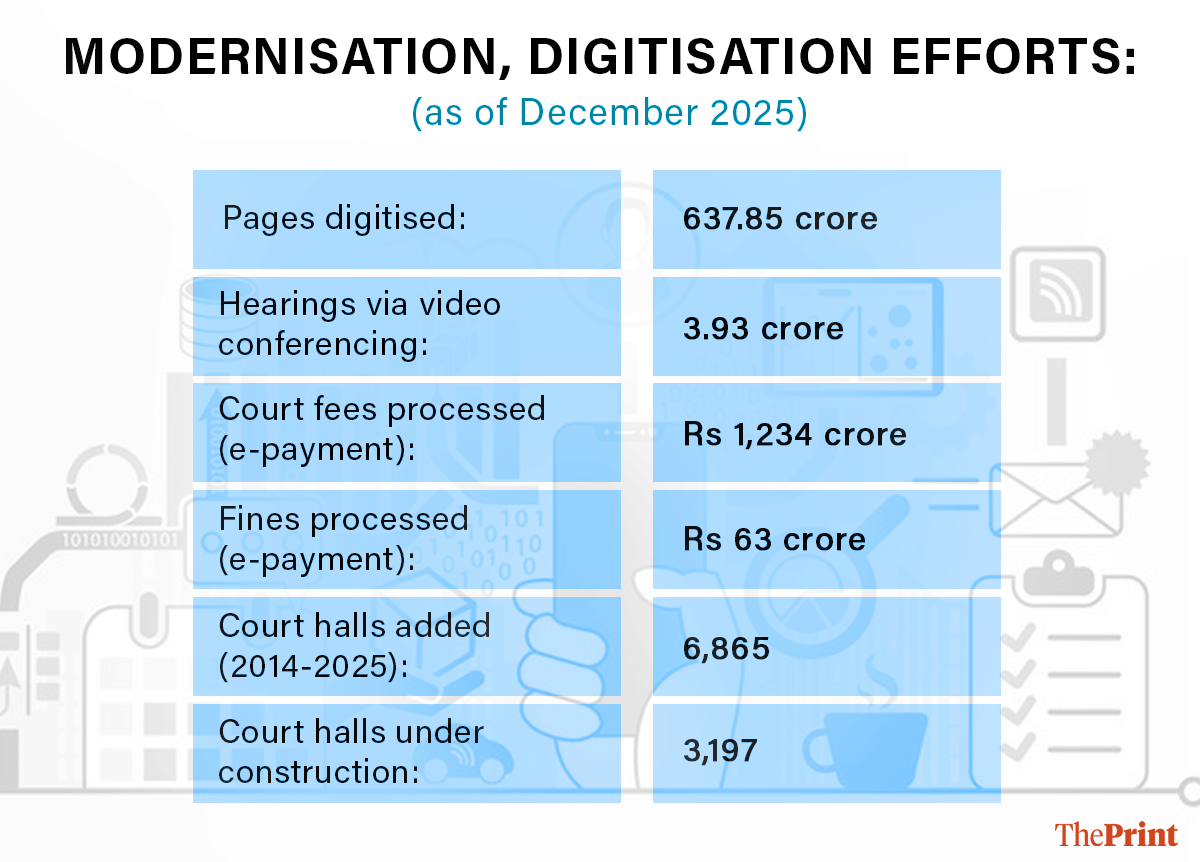

Government data showed that, as of December last year, 637.85 crore pages were digitised, 3.93 crore hearings conducted via video-conferencing, and Rs 1,234 crore in court fees and Rs 63 crore in fines processed through e-payments.

Under the centrally sponsored scheme, Rs 12,461.28 crore was released to states and Union territories over the years. Another Rs 228.48 crore has been earmarked for video-conferencing upgrades.

The number of court halls, too, rose from 15,818 in 2014 to 22,683 as of December 2025, with 3,197 more under construction.

The government said it has also established 774 Fast Track Special Courts (FTSCs) — including 398 exclusive POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) courts — funded in part by Rs 1,207.24 crore from the Nirbhaya Fund.

The vacancy & pendency gaps

Against this backdrop of expansion, the vacancy figures remain stark.

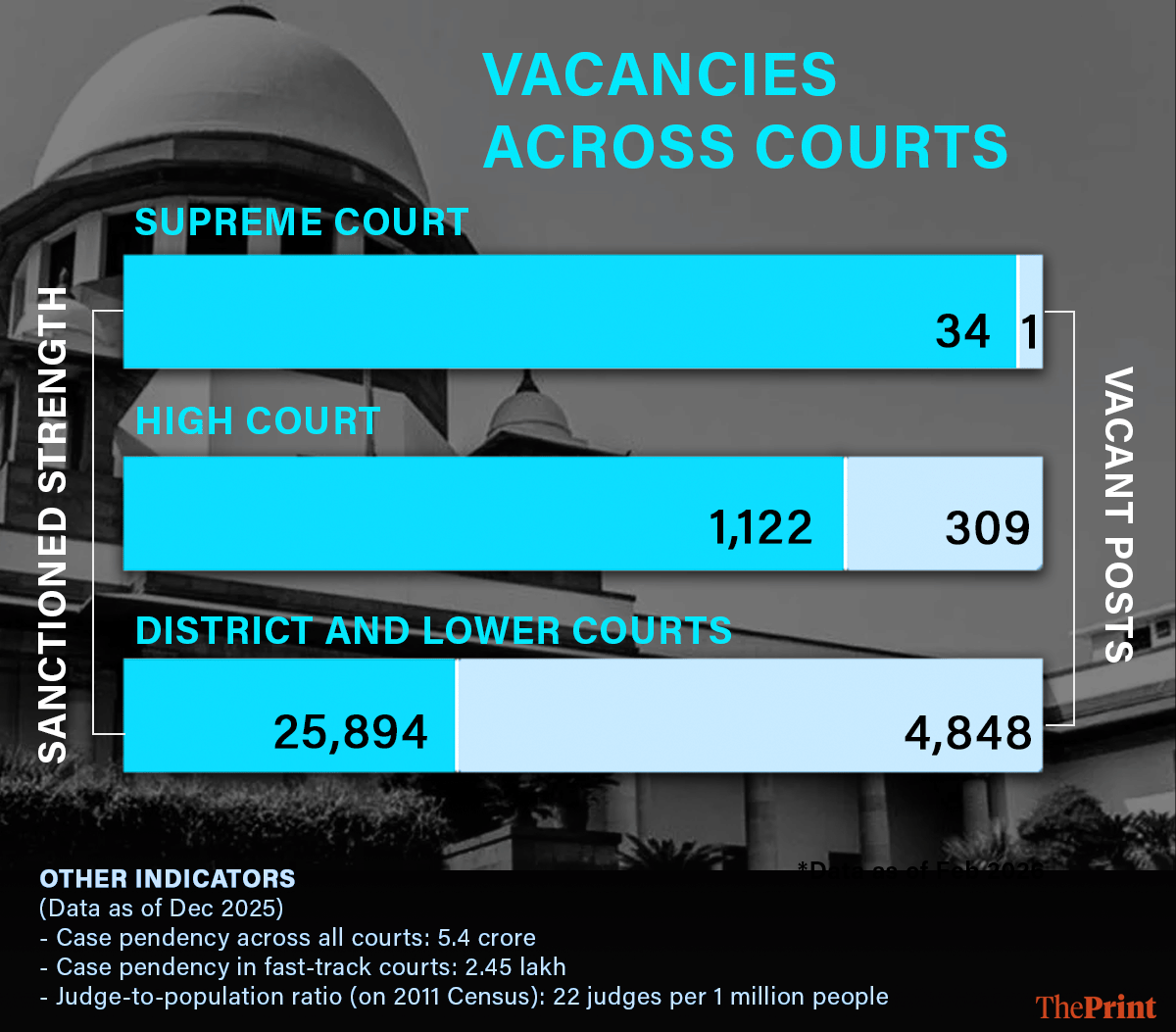

Currently, the Supreme Court has one vacancy against a sanctioned strength of 34. Across 25 high courts in India, 309 of 1,122 sanctioned posts lie vacant — approximately 27.5 percent of the total. In district courts, 4,848 posts are unfilled against a sanctioned strength of 25,894, about 18.7 percent.

Pendency of cases is another worry.

Government data showed the Supreme Court’s backlog of cases rose from 82,674 in 2023 to 92,101, as of December 31, 2025, an increase of 11.4 percent. Overall pendency across all courts rose from 5,11,88,805 to 5,41,15,452 in the same timeframe.

The fast-track special courts (FTSCs)—established in 2019 specifically to accelerate justice—had 2.45 lakh cases pending as of December 2025. That 91 percent of these cases are related to POCSO offences was more worrying.

According to the law ministry, the average duration of a trial at fast-track courts stretched to 1,639 days in Delhi, 1,484 days in Tripura, and 1,350 days in Manipur. (Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu fared far better in this parameter)

The ministry acknowledged the problem, noting in its parliamentary submission that “pendency of cases in courts arise due to several factors, which inter alia, include complexity of the facts involved, nature of evidence, co-operation of stakeholders, viz., bar, investigation agencies, witness and litigants, the availability of physical infrastructure, supporting court staff, etc. besides the shortage of judges”.

It added that “the disposal of cases is within the exclusive domain of the judiciary” while affirming that the central government was committed to speedy disposal under Article 21 of the Constitution.

‘Utility of infra depends on multiple factors’

Former Chief Justice of the Orissa High Court, Justice S. Muralidhar (retired), who is now a practising advocate, cautioned against reducing the debate to a simplistic ‘money versus vacancies’ narrative.

“Having a certain number of judges by itself is not the only issue,” he said.

Digitisation, even in courts where vacancies are high, doesn’t mean that the investments will automatically go to waste.

“If judges are in place, of course, the infrastructure will be used to its full potential—that is the main point,” he explained. But utilisation of infrastructure, he added, does not hinge entirely on every sanctioned post being filled.

Muralidhar, who has also been a judge of the Delhi High Court and Punjab & Hayana High Court, flagged two deeper concerns. The first was auditing and sustainability: without proper accounting of previously allocated funds, fresh allocations risk underutilisation. And the second was compatibility and technical capacity. Supplying hardware without adequate technical manpower, maintenance systems or relevant software limits impact.

He pointed to the practical difficulty of courts relying on open-source systems when most lawyers draft documents in Microsoft Word and file annexures in PDF formats. If court software cannot seamlessly receive, open and process these formats, digitisation becomes friction rather than facilitation, he said.

Judges and staff, he added, also require training.

On representation, Muralidhar cautions against focusing solely on diversity at the bench. “We speak of diversity in the judiciary, but rarely examine diversity at the Bar,” he observes.

For him, the issue ultimately leads back to the educational pipeline. “You have to go back to the education system. How many students from marginalised communities enter quality law institutions? How many receive the exposure necessary to build successful practices?”

Without strengthening that pipeline, he suggests, debates about judicial diversity risk addressing only the surface of a deeper structural issue.

Also Read: 8.82 lakh execution petitions pending: The long wait for justice, even after victory in court

‘Who gets to sit on the bench’

For former Chief Justice of the Himachal Pradesh High Court, Justice Rajiv Shakdher (retired) the crisis is not simply numerical. The larger question, he said, was to see “who gets to sit on the bench”.

Shakdher, who served in the Madras and Delhi high courts, challenged the conventional reliance on ‘merit’ as a neutral benchmark.

Merit, he argued, cannot be assessed in isolation from social and economic context. Candidates from privileged backgrounds benefit from better schools, elite colleges and professional networks, making comparisons with those from marginalised communities inherently unequal—“like comparing chalk and cheese”, he said.

Data by the ministry bears this out.

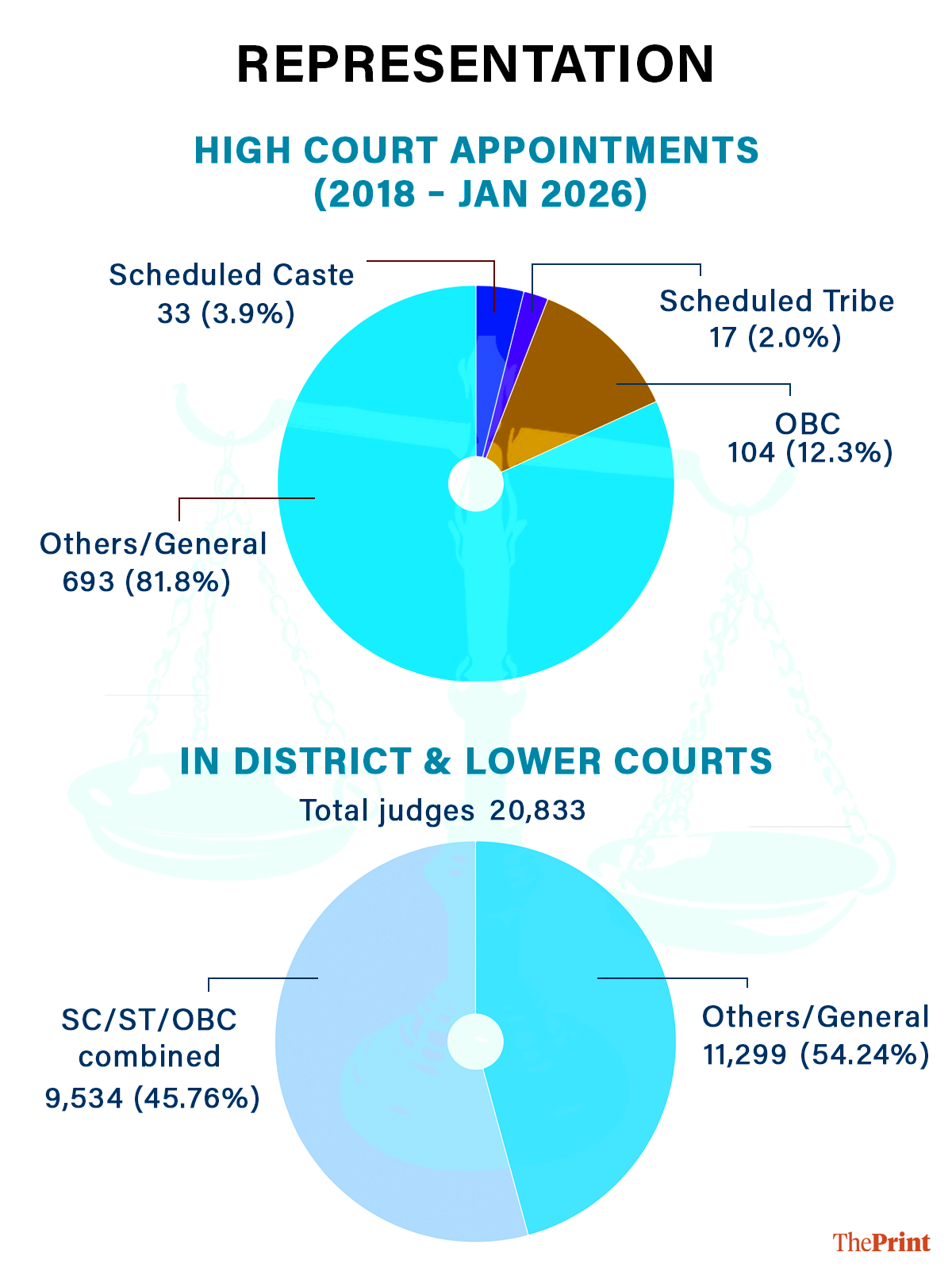

Of 813 working high court judges currently, only 116—14.27 percent—are women. The ministry does not provide similar data for judges in district and lower courts.

Among the 847 high court judges appointed between 2018 and January 2026, 33 (3.9 percent) belong to the Scheduled Caste category, 17 (2 percent) to the Scheduled Tribe category, and 104 (12.3 percent) to the OBC category.

An analysis of total workforce strength in district and lower courts, 45.76 percent of judges—9,534 out of 20,833—across India belong to SC, ST or OBC categories.

Shakdher acknowledged there was a concerted effort to improve judicial facilities and infrastructure in the country, but maintained that representation remains key to delivering justice.

Court orders, he said, are inevitably shaped by a judge’s background.

If the bench does not adequately reflect women and the marginalised communities—including SCs, STs and OBCs—that absence can affect both judicial reasoning and public confidence, he said. Litigants may leave courtrooms feeling their realities were not fully understood, “even if they cannot openly articulate it”, he said.

On representation of diverse communities in the judicial system, Muralidhar pointed out that the lens needed to go beyond the bench. “We speak of diversity in the judiciary, but we rarely examine diversity at the Bar. It’s very easy to say it lacks diversity. But how many Scheduled-Caste lawyers appear before the Supreme Court,” he said.

Shakdher also raised the question of sanctioned strength.

In courts like Delhi, he noted, the number of sanctioned posts were fixed years ago and have not kept pace with population growth or rising litigation. The same question, he said, applies to larger courts such as Allahabad.

India’s current judge-to-population ratio stands at approximately 22 judges per million people, calculated using 2011 Census figures. This ratio in 2026, he said, is likely to be more skewed, if updated population figures are accounted for.

Ultimately, the root of the problem can be traced to the legal education pipeline.

Beyond the National Law Universities and a handful of established institutions, many law colleges lack the infrastructure, faculty strength and academic rigour needed to produce competent lawyers who can later enter the judiciary, Shakdher said.

“Unless the system rethinks where and how it cultivates its lawyers,” he warned, structural deficits in representation and capacity will persist.

Without holistic improvement across the board, India’s judiciary may not always be able to deliver what it was built for: justice.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: Saket court staffer suicide: Delhi HC orders audit of vacancies & staff workload, no FIR