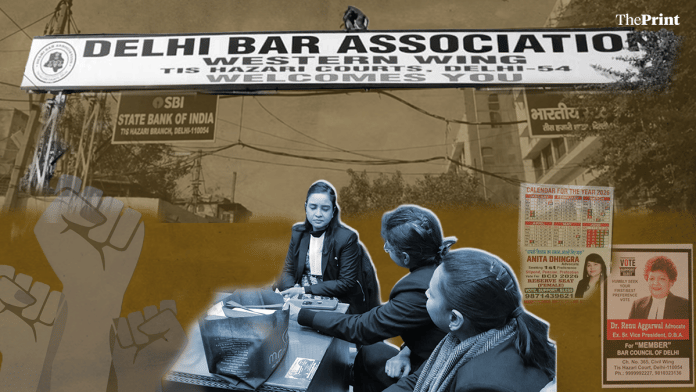

New Delhi: The western wing of Tis Hazari hums with its familiar lunchtime buzz in the January chill. Files fly, lawyers rush, and the canteen is chock-a-block. But amid this everyday rhythm of the court complex, the chatter is less about cases and more about women contesting the Bar Council of Delhi elections.

The Bar Council of Delhi—the country’s largest—is a statutory body that regulates legal practice in the Capital, including the enrolment of advocates, disciplinary proceedings, and welfare measures. However, women lawyers have historically remained largely absent from the leadership of the council.

A Supreme Court direction from 8 December last year has sought to alter this landscape by mandating the reservation of five of the 25 elected seats on the Delhi Bar Council for women.

As the February 2026 elections draw near, history is in the making—a shift that now dominates conversations across court premises.

>Advocate Anju Dixit steps out of her grey Thar early afternoon, back from Rohini court after a campaigning session there. Walking across the Tis Hazari court’s civil wing, colleagues who recognise her stop her frequently, wanting to know more about the upcoming elections.

Dixit has been in practice for nearly three decades. Yet, this is the first time she is contesting the Bar Council elections.

“This reservation is a first, so we built up some courage… God has given us a lot of calibre. Women should step forward now,” she says, her face beaming with a first-timer’s delight.

What the Bar does & why it matters

Governing one of the country’s largest and most diverse legal communities, and historically almost entirely male in its leadership, the Bar Council of Delhi has been a paradox.

Elections to the council are held once every five years, with enrolled advocates voting to elect 25 members. They go on to shape policy and administration within the profession.

Up until now, the Bar Council of Delhi had elected only two women. Now, in 2026, that record is finally being put to the test.

Five of its 25 elected seats are reserved for women this time, with two more to be filled by co-option—a structural opening created by judicial intervention, but intended to be carried forward by women willing to contest.

With over 1.65 lakh registered advocates as of January 2026, the Delhi Bar Council is the largest in the country.

The Supreme Court intervened after women approached the court, highlighting the structural exclusion of women from leadership positions in the Bar across the country. The court noted that despite a growing number of women entering the legal profession, institutional power within bar councils remained overwhelmingly male-dominated.

Unlike loud political contests, Bar Council elections are fought in small, personal exchanges—a word outside a courtroom, a handshake near the canteen, a message on WhatsApp.

Many women candidates say balancing court work with campaigning has meant longer days and fewer breaks, but also a heightened sense of visibility.

Court-to-court, chamber-to-chamber

For Advocate Vani Singhal, who practises civil and commercial law, the change is overdue.

“Earlier, the Bar Council was almost entirely male,” she says, handing out her election postcard with folded hands. “There was no female lens to address female problems.”

Issues like the lack of washrooms, the absence of complaint mechanisms, and everyday indignities were rarely treated as institutional concerns, she says. “With women there, priorities will change.”

Advocate Anushkaa Arora juggles client meetings with short campaign stops between court hours. Enrolled in 2018, she says the reservation has made leadership feel within reach for younger advocates.

“This has given women the confidence to come forward,” Arora says as she calls up a fellow lawyer for a chamber campaign. “If I get elected, it’s not just about women; it’s also about young advocates finally being heard,” she adds.

Advocate Mobina Khan’s campaign is leaner, shaped by one-on-one conversations in corridors and chambers. Having shifted from railway empanelment to litigation, Khan says advocates repeatedly raise the same concerns with her.

“There are no basic facilities for general advocates. People want someone who will actually listen and be available,” she says, adding that one of her agenda points includes a 24/7 helpline for general category lawyers.

Across courts, their concerns are rooted in lived experiences—unsafe workspaces, lack of dignity in daily practice, and the absence of clear forums for grievance redressal. Others speak of welfare—support for young lawyers, pensions for seniors, and transparency in the council’s functions.

Balancing practice with campaigning remains a challenge. Many women candidates admit their court work has been affected, with juniors and colleagues stepping in to manage cases. Still, several describe the process as energising rather than draining—an opportunity to be visible, heard, and taken seriously.

What unites them is the sense that simply being in the race marks a shift.

What is already clear is that the presence of women candidates—confident, insistent, and visible—has changed the contest. In corridors that once assumed leadership was male-dominated, women are no longer asking for space—they are claiming it.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)