Khliehriat: Chandra Rai, 45, hasn’t left the site of the coal mine in Meghalaya’s East Jaintia Hills for the last two days. He was just 30 minutes away, at another mining site, when the blast took place. He saw many rescue teams arrive and several bodies being taken away, but he couldn’t find his brother-in-law. His wife has called multiple times asking for updates.

“He came here three-four months ago for work. He was earning Rs 1,000 every day and sending the money back home. I am just waiting to get his body. He was inside the mine and the forces are trying to find him,” Rai told ThePrint, sitting on a rock in front of a well dug for coal mining.

The explosion at the “rat-hole” coal mine in the East Jaintia Hills Thursday morning has claimed 27 lives so far, including two more bodies recovered Saturday.

Rat-hole mining involves digging of narrow underground shafts, termed “rat holes”, through which labourers crouch or crawl to extract coal. Most of the extraction is done manually but controlled blasts are often used to break open the tunnels. The National Green Tribunal had banned rat-hole coal mining in Meghalaya 12 years ago.

On Thursday, some labourers working in nearby mines heard the blast but initially didn’t react, as such sounds were not unusual for them. However, when they heard people shouting and learned about the deaths, they were shocked.

“People gathered, families came, but everyone got so scared. Those who were outside were found quickly, but those who were inside the small mines are still missing,” said a labourer working in the mines, requesting anonymity.

“We have found two bodies today deep inside these rat-hole mines. Three large wells had been dug up, and inside them there are multiple small tunnels, and more tunnels within those—it is like a web. Some parts are waterlogged as well, so it is difficult, but our rescue operation is ongoing,” H.P.S. Kandari, the NDRF (National Disaster Response Force) commanding officer present at the site, told ThePrint.

Most of the labourers there are from different parts of India, including Assam and West Bengal, as well as from Nepal. More than 100 temporary houses in the mining area are now empty, as most labourers have fled. Only the family members of those trapped inside remain, waiting for the bodies.

Some labourers said they had travelled this far because the high-quality coal found at the site paid well.

“We have come this far because the coal quality is good and we get paid well for it. Sometimes we earn Rs 3,000 after working day and night,” said Tara Munget, a labourer who started working at the mines two months ago.

Munget had come for mining work for the first time but has now decided to return to Nepal to look for other work.

The coal mines are located deep inside dense forests. The pathways are filled with coal dust and steep, bumpy tracks. One needs four-wheel-drive vehicles to reach the site; regular cars cannot travel deep inside the jungle terrain.

“We came here two months ago. Food and other essentials were provided. Some people lived here with their families and everyone used to eat together. Now everything is empty. Those who couldn’t get vehicles ran barefoot carrying their belongings,” said Munget.

Also Read: Search for Meghalaya miners’ bodies has become an expensive & hopeless wait for a miracle

A look at rat hole mining

The entire hill is dotted with rat-hole mining sites—an illegal method of coal extraction. A crane is used to dig a large vertical well. Labourers then descend through the shaft, sometimes as deep as 100 feet. From there, they dig narrow horizontal tunnels, just 2-3 feet wide, continuing as long as coal seams are found.

“The labourers crawl inside these narrow tunnels and dig coal. From one tunnel, they create more tunnels, forming a web-like network underground. Some of these extend 300-400 feet,” said an official present at the site.

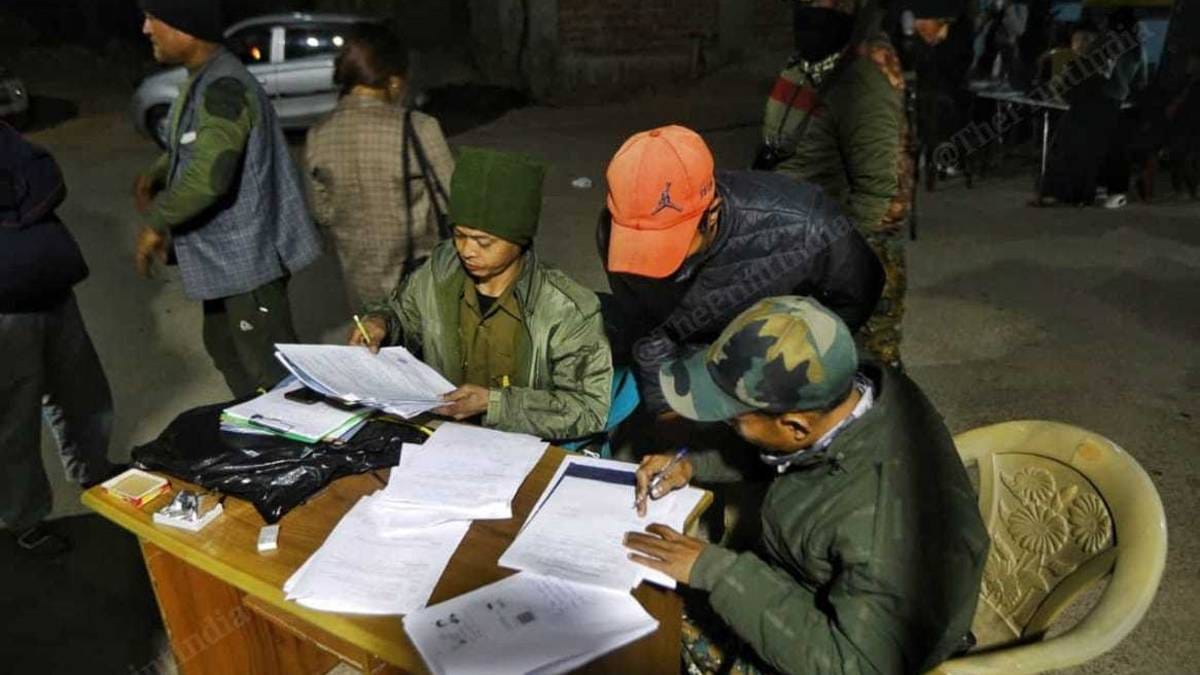

Three NDRF teams are currently deployed at the spot searching for bodies. The State Disaster Response Force, Border Security Force, and local police are also present, along with medical teams to provide assistance if required.

The area is deep jungle—only dust-covered hills and trees are visible. While travelling to the site, one can spot hundreds of huts made of blue tarpaulin and bamboo. Most are now deserted. Inside one hut, around six temporary beds made of bamboo sticks and hard boards were set up.

“All of us used to sleep together after work. Now many are dead and their belongings remain. Medicines and clothes are lying inside, but no one is here to collect them. Who will come? Their families live far away,” said Munget, pointing towards the huts.

Rai and Munget watched multiple bodies being transported from the mines to hospitals. Each time, they held their breath, fearing it might be a relative. Each time it wasn’t, they felt both relief and renewed trauma.

“It would have been easier if I had found the body. Now with each body, I have to relive the trauma again. I have seen so many bodies—they will haunt me for a long time,” said Rai, staring at the mining site where the NDRF rescue operation continues.

Many political leaders have reacted to the tragedy and Prime Minister Narendra Modi has announced financial relief for the deceased. Their families will get Rs 2 lakh each while the injured will be given Rs 50,000. However, families of the victims claim that no official has met them so far.

“Money is a different thing. No one has come to even meet us. We are poor people, our lives don’t matter,” said Rai.

Soon after Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma promised strict action against those operating the illegal mine, the police arrested two individuals identified as Forme Chyrmang and Shamehi War. Both were produced before a court and remanded to three days’ police custody.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Another year, another mining tragedy — why Meghalaya’s ‘rat holes’ won’t stop killing