Hisar: “No Mughal ever ate Mughaliya food, because Mughaliya food is defined by the hotness of chilies,” says the speaker on stage. Why? Because chillies were not to be found on the Indian subcontinent before the 16th century. The age-old debate between Bengal and Odisha on the question of who created Rosogolla is moot when you consider that the main ingredient of the modern rosogolla, the cottage cheese, was nowhere to be found in India till the Portuguese arrived.

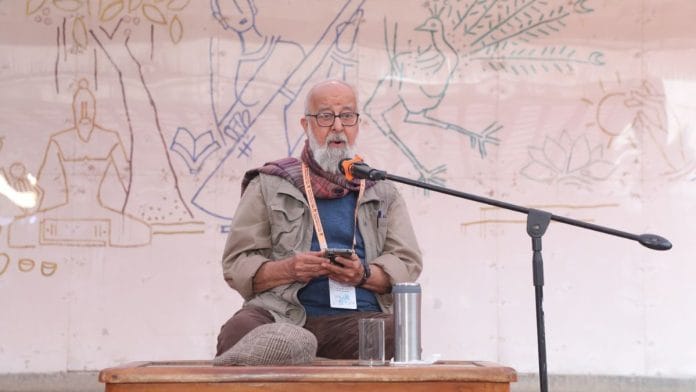

Speaking on the first day of the Jindal Literature Festival, oral historian Sohail Hashmi, with all the flair of the seasoned storyteller that he is, traced the evolution of the cultures of India back to a millennia ago, connecting the dots between actual history and fictional accounts, debunking narratives that have become entrenched in our visions of the past.

“The entire idea of my presentation is to talk about how things are connected, and how narrow minded is the idea that this is ours and this is somebody else’s,” Hashmi said.

Expanding on the idea, he talked of five plants that are, today, rooted in Indian cuisines and culture—chillies, tomatoes, tobacco, brinjals and datura. The first three are not native to the subcontinent. They came from South America. India gave to the world brinjals. The poisonous datura has been offered to Lord Shiva since at least the tenth century. But despite different points of origin, all the five plants come from the same family—Solanaceae, the nightshade.

Hashmi then turned the conversation to clothes. “In Bengal, the Brahmo Samaj in the 19th century began propagating the wearing of the blouse,” he said. The Brahmins attacked them for destroying the traditions of Indian culture, he said.

On the other hand, from the other end of the country, Hashmi recalled another story, that of a social reformer in Kerala gifting his wife a blouse. In jail for nationalistic activity in the colonial era, he received a letter from her which said, “This garment for the upper part of the body that you have gifted me, your mother will not let me wear it.”

Wearing the blouse, at the time, was seen as a sign of immorality because unstitched garments were the tradition. Why? Because scissors were not Indian.

The subcontinent had no scissors until the Greeks brought them. “And that is why no stitched cloth is of Indian origin,” explained the scholar.

“The apple, the pomegranate, the plum and the apricot, the watermelon and the musk melon—all these fruits were introduced to India by someone that we love to hate because somebody demolished a temple and built a mosque in his name—Babur,” said Hashmi.

These fruits did not exist on the subcontinent before the 16th century. “Think of how sparse our tables would be if all these fruits go away,” he mused.

Across history, ingredients and tools have traversed the world and become integral to the regional cultures which adopted them. “That is how national identities are made,” he added.

Diverse influences from all over the world have combined together to make the world what it is today. “We must remember that before 15th August 1947, there was no Pakistan, there was no east Pakistan. Hundred years before that, there were no national borders,” Hashmi concluded. “The idea of a nation is a 19th century construct. There were no nations before that. People travelled where they wanted and nobody asked them where they came from or where they were going. People settled all over, and they carried their food with them, they carried their spices with them.”

ThePrint is the official media partner for the Jindal Literature Festival.

(Edited by Viny Mishra)

Also read: The deer, the man and the trap: A Kathak recital turns allegory into atmosphere at Jindal Lit Fest