Leh: A football match is in full swing on an open ground, the intensity rising with each pass. Students cheer their teams, while a staff member keeps score. In winter, the ground transforms into an ice hockey rink. It is part of a sprawling experimental school campus, set against the backdrop of towering Himalayan peaks, that extends beyond the colourful walls of its classrooms to weave in culture, sustainability, life skills and self-reliance.

This is the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) in Phey village, conceptualised by a group of Ladakhis, most prominently climate and education activist Sonam Wangchuk. SECMOL was built on the principle of ‘learning by doing’.

Padmang Moey, an 18-year-old from Changthang who enrolled at SECMOL’s foundation course after her Class 12 exams, says the school helped her discover her interests. “It has helped me gain self-confidence and gradually I am understanding my areas of interest. It is shaping me into becoming more self-confident. I am learning public speaking skills.”

The school’s philosophy is visible across campus, from the walls of its buildings to the daily routine of students, where the focus shifts from 3R to 3H—Reading, Writing, Arithmetic to Heads, Hands, Hearts or critical thinking, practical skills and empathy.

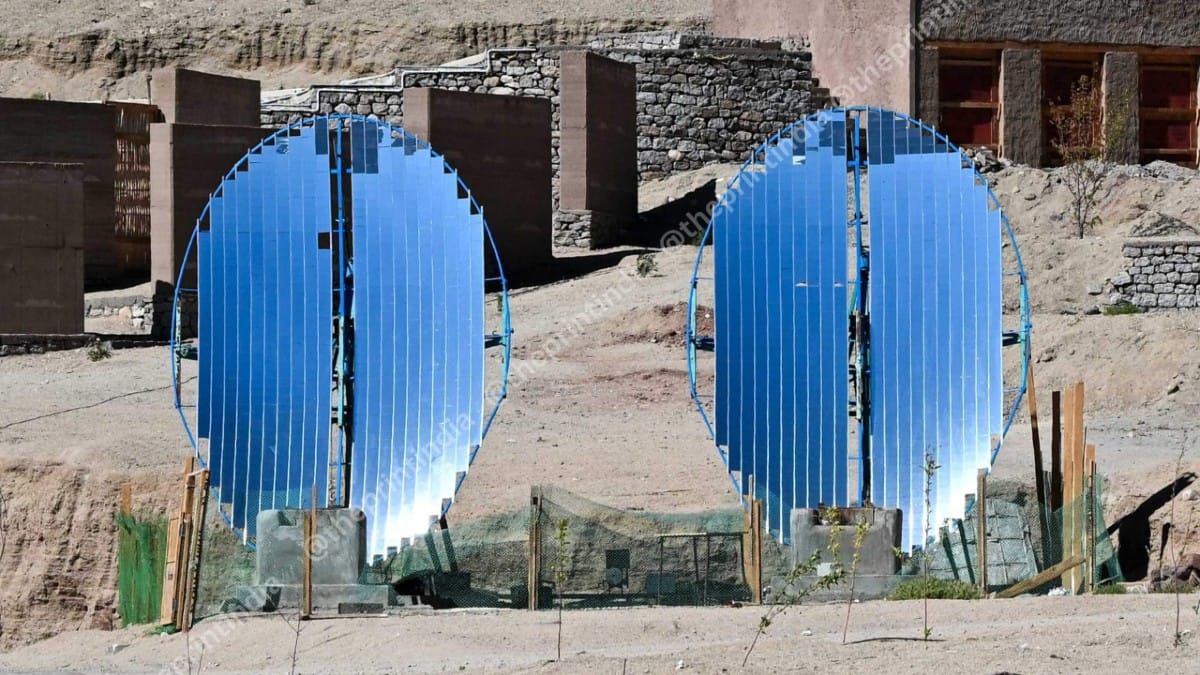

Every corner tells a story, every space holds a lesson, turning the campus into a place of continuous engagement and growth. The walls are decked with murals made by students, the dorms lined with carefully crafted bunk beds; solar cookers gleam under the sun, and the grounds are home to greenhouses that supply fresh vegetables. The off-grid campus even has its own natural underground freezer to store vegetables and other essentials.

The community also relies on compost sanitation systems.

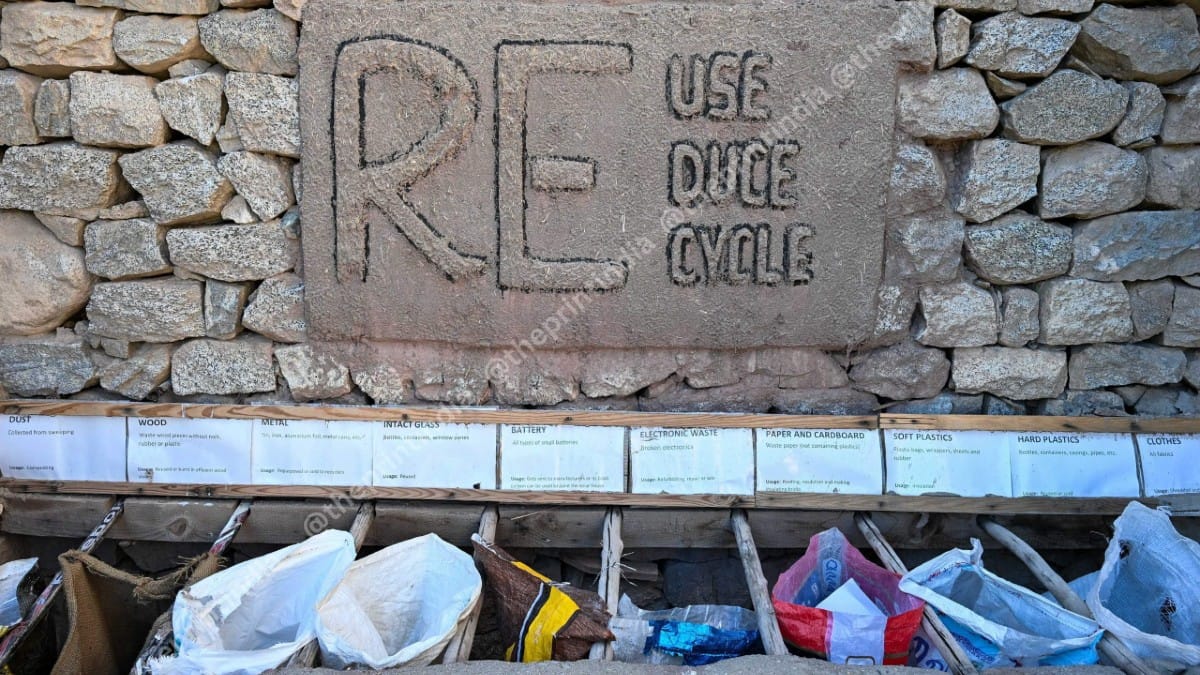

Further, workshops provide spaces for practical learning and hands-on projects, carpeted classrooms host pre-dinner cultural talks and music sessions, and every corner has bags for each type of waste with ‘Reuse, Reduce, and Recycle’ inscribed on the rocks above it.

The efforts have paid off. Since its founding in 1988, SECMOL has nurtured a host of students who have gone on to become video journalists, national-level ice hockey players, founders of all-women travel companies and even leaders running the very school they once attended. Yet today, the NGO behind SECMOL, which once drew national and international attention not just because of its adaptation in the movie 3 idiots but also for its alternative approach to education, is under scrutiny. The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has cancelled its FCRA license, citing alleged violations, such as receipt of funds from a Swedish platform to conduct a study on “sovereignty of the nation”.

Another of Wangchuk’s initiatives, the Himalayan Institute of Alternatives, Ladakh (HIAL), just a few kilometres away in Phyang village, is also facing similar charges. Even the 150 acres of land on which HIAL stands is at risk of being taken over by the government.

But HIAL co-founder and Wangchuk’s wife, Dr Gitanjali J. Angmo, rejects the charges. The government, she says, interpreted “food sovereignty” as national sovereignty in SECMOL’s case. “Students come to SECMOL and stay here for a year, and the whole school replicates their home, unlike other schools. Students here run the school, they grow their own food. Unlike other NGOs, we don’t take funds for daily operational costs,” she told ThePrint.

For students of SECMOL and HIAL, these institutions situated in the cold desert are more than schools—they are spaces of freedom and creativity, where their ideas, talents, and voices can flourish.

While SECMOL has transformed over the years into a hub of experiential learning, HIAL, established in 2018, continues to evolve into an institution focused on an inclusive and sustainable education model where fellows work on their own projects as well as innovative campus projects such as building passive solar-heated building architecture prototypes.

Also Read: On Sonam Wangchuk’s arrest, wife Gitanjali Angmo stands firm—‘he’s a Gandhian, not a threat’

‘Didn’t know what to do with my life’

Students ThePrint spoke to say SECMOL’s courses offer them a second chance. Many of them were clueless about what they wanted to study after their Class 10 exams, but the school gave them direction, and many of them now work at SECMOL.

A 33-year-old former student, now one of SECMO’s four core members, says the institution showed him the way. “I failed Class 10 and didn’t know what to do with my life. My English was poor, confidence at its lowest,” he recalls, showing the first-ever room built in SECMOL.

Then, in 2015, he arrived at SECMOL, his second chance at life. Here, he wasn’t merely taught various subjects, but also life skills. He returned to take his Class 10 exams, went on to secure a postgraduate degree in Geography, all the while volunteering at the school.

Today, he teaches Geography at SECMOL, one of many alums who returned to give back to the school. Padma Othsal, now campus director, began in the foundation course, and renowned filmmaker Stanzin Dorjai, another alum, serves as president of the Board.

Descau Namgyal, a 17-year-old from Khardong village, around 70 km from Leh, came to study here some four months ago. Like many others, he too didn’t know what he wanted to study after his Class 10 exams. “I couldn’t decide what I would want to do, and so I decided to come here … to experience new things, learn things practically and grow.”

SECMOL selects students for its foundation courses offered in gap years from among students who attend the summer camp. Those who can afford it pay Rs 3,000 a month—including food, education and lodging—while others receive full scholarships.

Besides foundation courses for those who clear classes 10 or 12, SECMOL also has courses for those who failed Class 10, an idea that stems from Wangchuk’s early initiative to tutor such students. This was when he returned to Ladakh with a BTech degree.

A typical day at SECMOL starts at 5 am. Those on kitchen duty prepare the meals for the day, and between 6:30 and 7 am, everyone exercises with picturesque mountains in the backdrop. This is followed by a talk session, library visits and a community breakfast.

After breakfast, students are engaged in a host of activities from gardening and cleaning to farming. Apart from this, the academic curriculum offers classes in Solar Science, English, Geography, Sociology and Sports Theory.

The institute also has programmes like women’s leadership and public speaking courses.

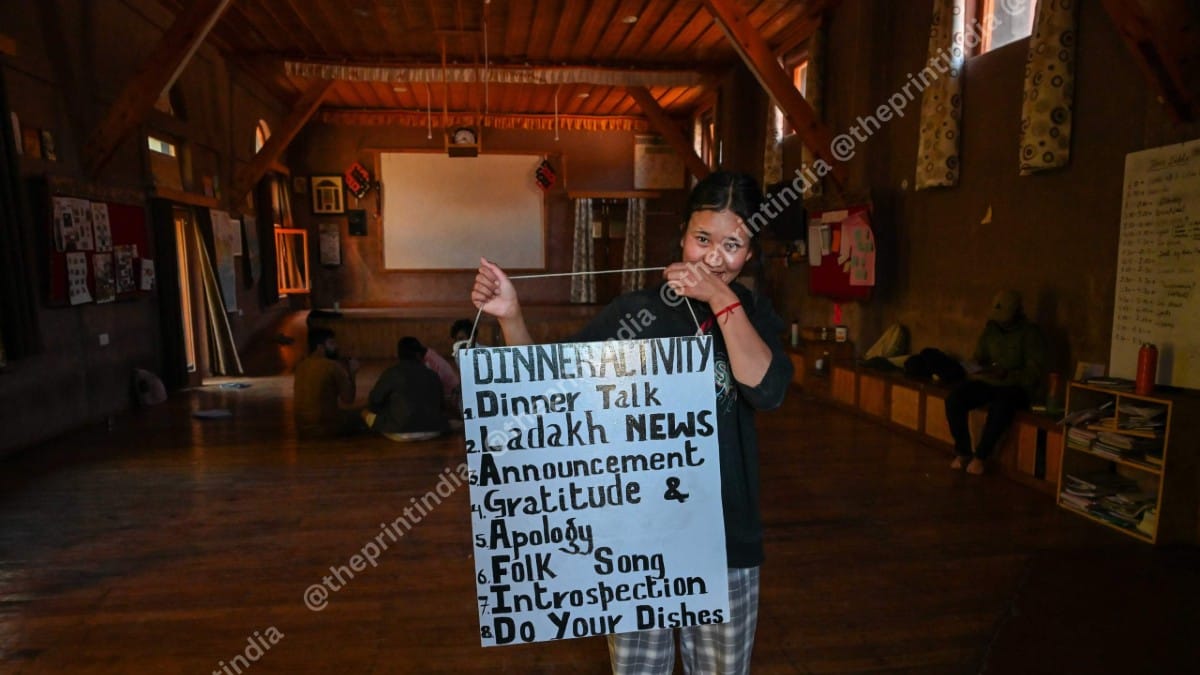

During dinner time, students dive into intellectually stimulating conversations about their lives, peer learning and news about Ladakh. They also offer gratitude and apologies to each other, sing folk songs, introspect, and finally, after dinner, do their own dishes.

SECMOL’s influence extends far beyond academics. Many here say half of India’s women’s ice hockey team is SECMOL-trained, including Tsewang Chuskit, the current captain who led the team to a historic bronze at the 2025 IIHF Asia Cup in the UAE, and appeared on Kaun Banega Crorepati (KBC) this August.

Spalzes Angmo, a 36-year-old former student from Wangchuk’s tiny native village of Uleytokpo, was a part of the SECMOL ice hockey women’s team. “At a time when education was difficult for the people of Ladakh, I not only studied here as a young girl but also played ice hockey,” says the mother-to-be who now runs a grocery store.

At the heart of the SECMOL campus stands firm a car house built by students—a white jeep that symbolises the movement Wangchuk began in the 1980s to reform education in Ladakh. Students have decorated it with traditional Ladakhi clothes and some other antique items from the time it was established.

According to Wangchuk’s family and the campus director, while the activist continues to contribute to SECMOL, he isn’t a member of the Board. “He wanted to move on to bigger projects and give Ladakh bigger institutions,” says his brother Sonam Dorjay, who worked alongside Wangchuk to establish SECMOL.

Data scientists, MBA grads at HIAL

While SECMOL is a school rooted in the idea of a self-sustaining community, HIAL is more of a university-level experiment, though based on similar principles. Currently home to 40 fellows, HIAL has students from all over the country, among them engineering, arts and commerce graduates.

At HIAL, a centre for experiential learning, graduates are offered both 11-month fellowships as well as short-term courses of three to six months on subjects such as Ecology, Entrepreneurship, Tourism and Architecture. The fellowships are free of cost as HIAL is based on a model where students work on projects to pay for their education.

Aditya, a 25-year-old from Bangalore, joined HIAL in July as part of a fellowship.

“I am studying eco-responsive building and a minor in education. I was a data scientist before this. A friend of mine told me how Sonam Wangchuk built this institute here to bring sustainable solutions, especially for the mountain community. I trek a lot and spend a considerable amount of time in the mountains, which is why this felt like something I would like to invest in,” he says.

HIAL has DIY labs where students work on their projects as well as HIAL’s projects, such as the Ice Stupas, an artificial glacier devised by Wangchuk in 2013 to store winter meltwater for use in the growing season.

Like SECMOL, students here also prepare their meals using solar energy. At the community centre, everyone eats together, washes their dishes and carefully segregates the waste post-meals.

The campus has five passive solar-heated building prototypes with rammed earth and straw-clay walls. HIAL also has its own in-built system to keep track of the impact on its solar passive-heated buildings.

Another fellow, 23-year-old Hritesh from West Bengal, has a BTech degree in Computer Science from KIIT in Bhubaneswar. He came to study and work on HIAL’s Ice Stupa project that Wangchuk initiated in 2013.

According to Dr Angmo, 400 students have so far graduated from HIAL, now accused of offering students degrees without UGC clearance. The co-founder, however, rejects the accusations, saying that UGC clearance isn’t mandated for private institutions.

Gitanjali Mane, a 24-year-old from Pune with an MBA in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, is an HIAL fellow who participates in peer learning at SECMOL and also teaches management there. “I have been following Sonam sir’s work since Class 12. I wanted to be part of an experiential learning environment and see firsthand how hands-on learning works on the ground,” says Mane, who worked as a senior marketing manager at Bajaj Allianz for a year and a half. She adds, “I am currently working on edu-tourism, exploring what aspects of Ladakh, such as its geology, geography, and culture which I can share with the world.”

With both SECMOL and HIAL facing an uncertain future, the atmosphere is tense on both campuses. Still, staff, students and volunteers go about their daily lives while Wangchuk languishes behind bars at Jodhpur jail, more than 1,500 km away.

This is an updated version of the report.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Leh Apex Body says no talks until peace restored, govt’s delays turned Ladakh into pressure cooker

I wish Indian corporates would start investing in serious indian innovations and creations through their CSR budgets. Sonam Wangchuks efforts are internationally recognised but are ignored/ bypassed by nationals. Sad state of affairs as they keep complaining of lack of innovative ideas among Indians .

Very sad that “the powers to be”…. mostly in Lutyens Delhi fail to see the promise & benefits of such schools, that promote, develop and instill values of self-sufficiency are “punished” on one ground or excuse or another….

HOW DARE THEY… appears to be the basic values and thinkng behind these Lutyens Officials… in “far away” …. Dilli… Shame on Them..

????

There are a lot of mistakes in the news outlet and wrong information. Please correct the information; you also need to correct the location details and certain words.