New Delhi: A bunch of floral and fruity. A little bit of sweet. And woody. And nutty. And minty.

This description from a graph, of a scent of rose – which would be considered intangible by most – now has legal recognition associated with a tyre manufacturer.

The Trade Marks Registry last week accepted India’s first-ever olfactory trademark applied by Japanese firm Sumitomo Rubber Industries, and recognised “floral fragrance/smell reminiscent of roses as applied to tyres”.

Filed in March 2023, the trademark application by Sumitomo challenged long-standing assumptions about what can be protected under India’s trademark law.

The company, whose application was termed “rare” by the Union Ministry of Commerce and Industries, sought to register the scent of roses for tyres under Class 12 (vehicles) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

Sumitomo had already secured trademark for the scent in the UK in 1990s, but its attempt in India needed to confront two statutory barriers – distinctiveness, under Section 9(1)(a); and mandatory graphical representation, under Section 2(1)(zb) of the Act.

Proving distinctiveness – and a Shakespearean argument

Sumitomo successfully argued before the Registry that the scent of roses on its tyres was inherently distinct because the fragrance bears no logical or functional link to tyres – a product ordinarily associated with the smell of rubber.

The Registry’s order records the crucial submission: “There is no smell which parallels the smell of roses and therefore, the moment we say ‘the smell of a rose’, it is clear to the perceiving public what the smell is.”

To reinforce this point, the company also invoked Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, quoting: “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

The Registry accepted that the fragrance would create a strong commercial impression.

“When a vehicle fitted with tyres containing the present smell passes by, a customer perceiving the smell in question will have no difficulty in forming an association between the goods (tyres) and the source of the goods (the Applicant),” it said.

The order added, “This experience would leave a very strong impression upon such a customer as it would be in stark contrast with the smell of rubber… Also, the scent of roses bears no direct relationship with the nature, characteristics, or use of tyres and is, therefore, arbitrary in its application to such goods.”

International precedents, including registrations in the UK, European Union, Australia, the US and Costa Rica – were cited by Sumitomo in its application too.

Also Read: New labour codes are a simplification that’s been long overdue. Its a strategic shift

A 7-dimensional solution

Distinction, it appears, was the easier of the two parameters to meet.

The main hurdle to getting the trademark was the Act’s requirement for graphical representation.

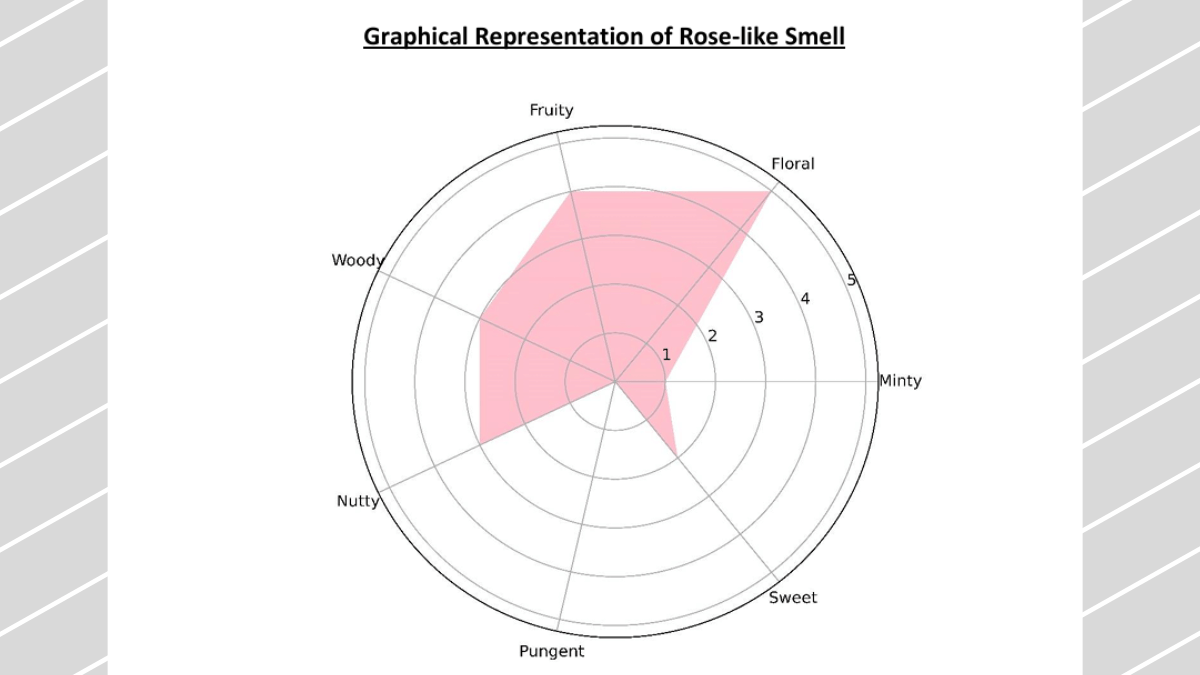

Amicus Pravin Anand worked on this obstruction by collaborating with scientists from the Indian Institute of Information Technology (IIIT), Allahabad. IIIT’s Professor Pritish Varadwaj, Prof. Neetesh Purohit and Dr Suneet Yadav helped represent the scent of rose as a vector in a 7-dimensional space.

On paper, the scent was expressed as a quantified vector depicting the composition, scale, and weightage of each component.

“A complex mixture of volatile organic compounds released by the petals interact with our olfactory receptors, creating a rose-like smell. Using the technology developed at IIIT Allahabad, this rose-like smell is graphically presented above as a vector in the 7-dimensional space wherein each dimension is defined as one of the 7 fundamental smells, namely floral, fruity, woody, nutty, pungent, sweet and minty,” the Amicus’ submission to the Registry noted.

In its order, the Registry noted that the representation met criteria laid down by the Trade Marks Act – it was “clear, precise, self-contained, intelligible and objective”. The scientific model, the order read, clearly defined the “metes and bounds” of the fragrance, fulfilling the mandatory graphical representation test.

India’s Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks, Professor (Dr) Unnat P. Pandit – who is a member of the Registry – also said in the order that the application satisfies all statutory conditions of the Act.

What is a trademark?

A trademark can be a unique sign, symbol, logo, word, and now, a scent, that identifies a company’s goods or services, distinguishing it from others. Once recognised, it can only be used by the company in whose name it is registered.

In its application, Sumitomo emphasised that the scent of roses was non-functional and did not serve any utility in its product – tyres. It was simply an identifier, which – the company said – met four key functions of a trademark – identifying products and their origin, guaranteeing consistent quality, aiding in advertising, and creating a product image.

“Considering these aspects, it is a possible moot that a ‘smell’ can be afforded the protection of trademarks too”, the Registry noted, adding that it can be advertised as an “olfactory trademark” in the Trade Marks Journal.

‘New era’ for intellectual property law

While traditional trademarks such as logos and symbols have been registered for long, India first recognised sound as a unique identifier in 2008, when Yahoo’s characteristic yodel was given a nod. A amendment in 2017 simplified the procedure to registering sound marks, provided they were represented graphically, typically through musical notations.

Another example of a sound mark is Netflix’s “ta-dum”.

Pravin Anand, who was amicus in the Sumitomo application, said in a statement on his website that India’s first ‘acceptance of a smell mark” has now opened the “door to a new era of non-traditional trademarks and signals a progressive shift in Indian IP jurisprudence”.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: Generic term, ‘lapses’ by registry—Delhi firm’s challenge to Dhoni ‘Captain Cool’ trademark bid