New Delhi: Amid objections from opposition benches over dilution of some key provisions related to liability of operators of nuclear power plants and suppliers of equipment, in case of an accident, the Narendra Modi-led NDA government passed the overarching Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill, 2025, Thursday. It is expected to change the trajectory of India’s nuclear energy production.

Once the SHANTI Bill becomes a law after assent by the President, it will remove the roadblocks that had so far held back private companies from participating in the nuclear power sector.

The Opposition across Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha had demanded that the Bill be referred to a parliamentary panel for scrutiny. But the government did not yield, impressing upon the Opposition that the law is necessary if India has to leapfrog from its existing nuclear capacity of 8.8 GW to 100 GW by 2047.

The SHANTI Bill repeals the two existing laws dealing with the nuclear sector—the Atomic Energy Act,1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage (CLND) Act, 2010.

While many of the existing provisions in the two laws have been retained in the SHANTI Bill, there are several new inclusions. ThePrint explains the key provisions of the Bill, how it is a step ahead of the two previous laws and how it will help India meet its target of producing 100 GW nuclear power by 2047.

Entry of private players

One of the most important provisions of the SHANTI Bill pertains to allowing private companies, registered or incorporated in India, to participate in nuclear power business in India. The Atomic Energy Act, 1962, has so far barred private sector participation in the nuclear sector.

Section 3 of the Bill states that private companies will be eligible to apply to the central government for a licence to build, own, operate or decommission a nuclear power plant or reactor. Private companies can also apply for a licence for fabrication of nuclear fuel, including conversion, refining and enrichment of uranium-235, up to such threshold value, or production, use, processing or disposal of other prescribed substances, as may be notified by the Centre.

Besides, private companies will be allowed transportation or storage of nuclear fuel or spent fuel, import or export, acquisition or possession of nuclear fuel or prescribed equipment, any technology or software that may be used for the development, production or use of nuclear energy.

Private companies will need to apply for licence and safety authorisation to do business. However, research, development and innovation activities will be exempted from the licence regime.

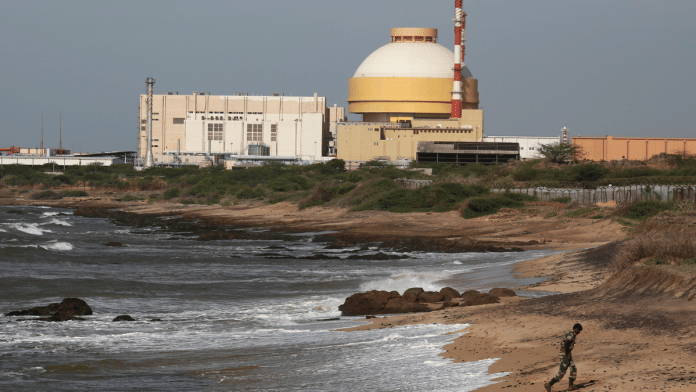

The entry of private players is expected to augment India’s meagre civil nuclear power, which is currently 8.8 GW or 1.6 percent of the total energy mix from more than 25 nuclear reactors in seven power plants across the country.

To put it in context, China currently has 57 operating reactors with an installed capacity of 55.3 GW and 28 more reactors (29.6 GW) are under construction as per International Atomic Energy Agency’s Power Reactor Information System.

Govt control

While opening the door for private players, the government will keep control of some crucial areas of the nuclear energy business. This will include fuel, safety and compliance infrastructure and mining and processing of certain source material containing uranium and thorium. The decommissioning of such mines shall also be carried out only by the government.

The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) has now been given statutory powers. It will have complete oversight to ensure safety compliance and technology compliance across all nuclear power plants owned by the government or any private company.

The source material and fissile material in any form, produced within India or imported, will remain under surveillance and control of the central government. Also, the spent fuel shall be safely stored for a cooling period of a duration determined by the AERB or for such further duration as the Centre may direct, before being delivered to the government for its subsequent management or repatriation to the country of origin.

The heavy water used in a nuclear facility shall also remain under government supervision.

Operators’ liability

The SHANTI Bill, while clearly spelling out the operators’ liability in case of nuclear damage or accident, has also introduced a graded structure of liability depending on the categories of nuclear installation.

The CLND Act, 2010, did not have this provision. For instance, in installation with reactors having thermal power up to 150 MW, the limit of operator liability has been fixed at Rs 100 crore. The maximum liability for operators has been put at Rs 3,000 crore for reactors of thermal power over 3,600 MW.

In the CLND Act, 2010, the maximum liability of an operator for each nuclear incident was Rs 1,500 crore for nuclear reactors having thermal power equal to or above 10 MW. This implied that the liability would be the same for a reactor having thermal power of 10 MW or 3,000 MW.

Clause 71 of the Bill also provides for jail of up to five years or fine, or both, for any person responsible for grave offences and a lesser punishment for less serious offences.

Stringent penalties have also been proposed for any person involved in breach or violation of the law. The penalty varies from Rs 5 lakh for minor breaches, to a maximum of Rs 1 crore for severe violations.

When does the Centre step in

While fixing the maximum liability of an operator at Rs 3,000 crore, the SHANTI Bill also specifies that the Centre shall step in where the liability exceeds such an amount, or when the nuclear accident has taken place because of a “grave natural disaster”. The Centre will meet its liability expenses from the Nuclear Liability Fund that it has been empowered to establish under the Bill.

The Bill also states that the maximum liability in respect of each nuclear incident shall be the rupee equivalent of 300 million Special Drawing Rights (SDR) or such higher amount as the Centre may, by notification, specify. The Centre may take additional measures, including seeking funds under the Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage signed at Vienna, if the compensation to be awarded under this Act exceeds 300 million SDR. India is a signatory to the convention.

SDR is an international reserve asset created by International Monetary Fund, the value of which is determined and allocated by it to member countries. In Indian currency, currently the value of 1 SDR is about Rs 130.

The Centre will also be liable if an accident occurs in a nuclear installation owned by it.

Besides, Section 14(1) of the Bill states that the Centre may assume full liability for a nuclear installation not operated by it, if it is of the opinion that it is necessary in the public interest to do so.

The nuclear liability provision of 300 million SDR has come under bitter criticism from the Opposition for being “grossly inadequate”.

Speaking on the Bill in Lok Sabha, Congress MP Shashi Tharoor said, “The core of liability reform caps total nuclear incident liability at 300 million SDR, which is approximately 460 million USD or Rs 3,900 crore…. This cap has not changed in 15 years despite inflation, despite Fukushima, despite everything we have learnt.”

Tharoor said the Fukushima disaster cleanup cost has already exceeded USD 182 billion. “That is several hundred times the cap proposed in this Bill today. Chernobyl’s total economic impact exceeded USD 700 billion,” he added.

Suppliers’ liability

Another key provision of the Bill which has invited Opposition criticism deals with the operators’ right to recourse against the supplier after paying compensation.

Section 17 of the earlier CLND, 2010, which deals with suppliers’ liability, has been tweaked in the SHANTI Bill.

Where earlier the CLND, 2010, provided for the operators’ right to recourse where a, it is expressly provided for in a contract in writing; b, where the nuclear incident has resulted as a consequence of an act of the supplier or his employee, which includes supply of equipment or material with patent or latent defects or sub-standard services; and c, the nuclear incident has resulted from the act of commission or omission of an individual done with the intent to cause nuclear damage. The SHANTI Bill has removed the suppliers’ liability as mentioned in clause b.

It instead states that the operators’ right to recourse will now be based on what is specified in the contract signed between the two parties. The earlier provision in CLND, 2010 had created apprehension among suppliers and was seen as one of the main reasons that private players stayed away from investing in the nuclear energy sector in India.

Compensation

The Bill lays out an elaborate structure for compensation to victims of nuclear accidents. It empowers the Centre to establish a Nuclear Damage Claims Commission to consider the extent and severity of nuclear damage and expedite claims for compensation. The right to claim compensation for nuclear damage shall extinguish, if such claim is not made within a period of 10 years, in the case of damage to property; or 20 years, in the case of personal injury to any individual, from the date of notification of nuclear incident

The Bill also specifies that any compensation for nuclear damage suffered can also be claimed, if it has occurred in the territory of a foreign state resulting from a nuclear incident in India, if at the time of such nuclear incident, the foreign state has no nuclear installation in its territory or its maritime zones established in accordance with international law; or is a party to one of the international conventions on civil nuclear liability.

(Edited by Viny Mishra)