This is the concluding part of a four-part series. You can read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

New Delhi: In the academic corridors of Delhi University’s Aryabhatta College, a unique project is underway. A group of academicians from the university are working to revive and reinterpret the contributions of some of the most well-known ancient Indian scholars in the fields of Mathematics and Astronomy.

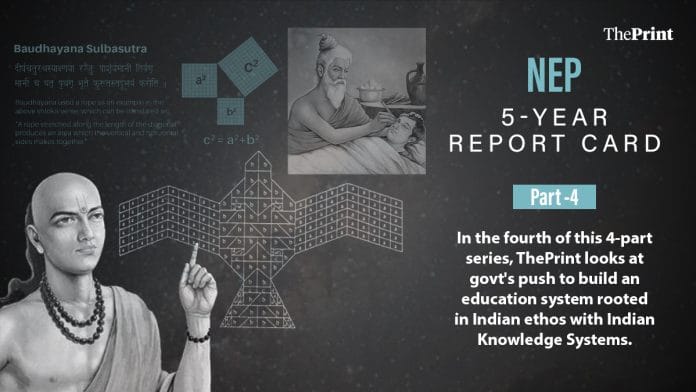

In a modest yet vibrant setting, academicians at this South Campus college are exploring key texts of ancient Indian Mathematics to trace the origins of mathematical concepts—the Brahmasphuṭasiddhānta by Brahmagupta (c. 628 CE), the Śulbasūtras (8th–2nd century BCE) on geometric altar construction, Āryabhaṭīya by Āryabhaṭa, and Gaṇitayuktibhāṣā by Jyeṣṭhadeva (c. 1530 CE), a foundational text of the Kerala school of astronomy.

The ongoing exercise in Aryabhatta College, besides several other higher education institutions across India, is part of the Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) programme under the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 that pushes for an education system rooted in Indian ethos.

The policy recommended incorporating elements of India’s traditional knowledge in the curriculum in an “accurate and scientific manner” in areas like Mathematics, Astronomy, Philosophy, Yoga, Architecture, Medicine, Agriculture, Engineering, Linguistics, Literature, Sports and Games.

So far, over 50 government-funded IKS centres have been established as part of the Centre’s effort to integrate traditional Indian knowledge into education.

After ancient Mathematics, the IKS centre at Aryabhatta College is soon set to begin its next major project on Indian Astronomy. A similar endeavour is underway across 49 other government institutions and research centres, including at multiple Indian Institutes of Technology.

For instance, the IKS centre at IIT Mandi is working on traditional Indian medicinal research, while IIT Tirupati’s centre is exploring Kalamkari art, natural farming, and ancient food preservation. At IIT Madras, the centre is dedicated to researching India’s scientific heritage, among other areas.

Project coordinator at Aryabhatta College, Priti Jagwani told ThePrint that the IKS centre there chose to focus on Indian Mathematics and Astronomy because the institution is named after the renowned mathematician and astronomer. “We wanted to honour Aryabhatta’s legacy, while contributing to a serious academic revival in these fields.”

The centre was set up in 2023 with a three-fold objective—to develop academic courses on IKS, to record and disseminate these courses as online lectures, and to organise Faculty Development Programmes (FDPs) for training educators in this domain.

Professor Jagwani said that the content developed by the team of experts highlights India’s significant contributions to Mathematics, and emphasised the importance of reclaiming and recognising this rich intellectual heritage.

“There is a vast treasure of scientific and mathematical knowledge in our ancient texts, much of which has either been overlooked or misattributed to the West. For example, what the world calls the ‘Pythagorean Theorem’ was documented over a thousand years earlier in the Baudhayana Śulba Sūtra, a foundational text of Vedic geometry. Unfortunately, this is just one of many examples where Indian contributions have been unrecognised or miscredited,” she said.

Highlighting the centre’s broader mission, Jagwani said, “Many advanced ideas found in the Vedas, Upavedas, and other ancient Indian literature are still relevant today. Through this Centre, we aim to study them rigorously and present them with academic and scientific backing so that India’s contributions to global knowledge are rightfully acknowledged.”

The Narendra Modi-led government has taken significant steps towards mainstreaming the IKS over the last five years, for which a dedicated division was established in 2020. Guidelines were issued for higher education institutions to develop IKS-focused courses. Elements of ancient Indian knowledge have now been incorporated in new school textbooks, and IKS research centres have been set up across various institutions.

In a significant boost, the IKS budget saw a dramatic 400 percent increase this year—from Rs 10 crore in 2024–25 to Rs 50 crore in 2025–26. The government also announced the setting up of a national repository for IKS for knowledge sharing in this year’s budget.

Additionally, the Union Ministry of Education last year announced a budget of Rs 405 crore for the IKS division to be spent over five years.

According to IKS National Coordinator Ganti S. Murthy, the biggest achievement of the programme over the past five years has been the growing academic seriousness around it. “First, there is now broad awareness about IKS across the country. Second, the nature of the conversation has shifted—from casual or fringe-level debates to serious, scholarly discussions. That is a very encouraging sign,” he told ThePrint.

Murthy added that people are no longer making exaggerated claims about flying saucers, nor are they dismissing everything as foreign imports. “Both of which are incorrect. Initially, IKS was disregarded by fringe elements. Now, it is gaining recognition within the academic community. However, it will take time to overcome the 150-year-long slumber.”

However, the initiative has continuously faced criticism from a section of academic circles. Last year, the All India Peoples Science Network (AIPSN), a collective of scientists, issued a statement alleging misuse of the IKS mandate in higher education, and warned against the inclusion of “pseudoscientific claims” in these courses.

Also Read: UK’s University of Bristol, 3 Australian universities get UGC nod to start India campuses

Separate division to promote indigenous knowledge

Three months after NEP 2020 was launched, the education ministry established the IKS division to revive India’s ancient intellectual traditions in a modern context. Housed within the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) in New Delhi, the division was meant to promote interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research grounded in indigenous knowledge.

The division has steadily expanded its scope since—from supporting research programmes and setting up dedicated centres, to launching internships and developing specialised academic courses.

Over the past five years, the division has funded around 100 projects, each with grants of up to Rs 20 lakh. In addition, it supports 27 research centres, 17 centres for teacher training and course development, and seven language centres. Each centre received between Rs 18 lakh and Rs 40 lakh. The division also offers paid internship opportunities to young scholars, with over 6,800 students having participated so far.

The topics of the over 100 government-funded research projects span a wide range of areas, including the impact of sāttvik food on gut health, prāṇa-based Vedic approaches to reducing suicidal tendencies, influence of Indian classical ragas on human cognitive function, and a study on the effectiveness of Krimighna Gana from the Charaka Samhita in treating bovine mastitis, among others.

Murthy said that over time, the quality of research proposals submitted to IKS under its Bharatiya Gyan Samvardhan Yojana—a competitive grant scheme—has steadily improved, with increasing interest from scholars across disciplines.

The division, through the various centres funded by it, is currently offering around 40 online and hybrid courses on topics, like Ayurvedic drug design, food science, natural resource conservation, the Bhagavad Gita, and Yogasutra—open to both students and faculty.

Murthy added that a growing number of institutions are independently offering IKS courses, and hosting seminars and lectures, without relying on support from the division. “It clearly shows there is a larger interest, which is very heartening,” he said.

To support the integration of IKS in education, the University Grants Commission (UGC) had issued guidelines in 2023, as part of the NEP 2020 roll-out, urging universities to incorporate IKS into their curricula. Following this directive, several institutions, including Delhi University, began offering related courses.

Last year, IIT Mandi faced criticism for introducing a mandatory IKS course titled ‘Introduction to Consciousness and Wellbeing’ for first-year engineering students, which included themes like “reincarnation”.

The division is also preparing to launch 17 minor courses. “It doesn’t make sense to offer a full-fledged undergraduate degree in IKS,” Murthy said. “So we are developing minor courses that students can pursue alongside their primary discipline. For instance, an Economics student will be able to study a minor in ‘Bharatiya Economics’, while also learning all the modern concepts included in the regular syllabus.”

Centres digging into India’s ancient knowledge base

Among the 27 research centres dedicated to IKS, the one at IIT BHU in Varanasi is playing a key role in revitalising traditional knowledge through interdisciplinary research, having received Rs 40 lakh in funding from the Government of India to support its initiatives.

According to Professor V. Ramanathan, principal investigator at the IKS Centre of Excellence at BHU, one of the flagship projects under the theme of Holistic Wellness involves the preparation of a herbal monograph using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LCMS). This scientific approach aims to make Ayurvedic practices comprehensible through modern analytical techniques.

In the domain of Chemistry and Archaeology, the centre has published two books on Indian rock art, integrating advanced tools, like Raman Spectroscopy and X-ray Fluorescence (XRF), with ethnographic research to uncover and preserve India’s ancient artistic and cultural legacy.

In the Maths and Astronomy domain, the centre has published a critical edition of the manuscript called Makarandopapatti, a medieval text outlining the astronomy practised in and around Varanasi. In the Darshana domain, it has published peer reviewed research papers showing the Indian parallels of the Ship of Theseus problem, a famous Greek philosophical thought experiment about identity and change over time.

“The central motto of our centre is rigorous research. It is easy to make tall claims without evidence. Our aim is to bring forth the scientific achievements of India’s past thorough research and verifiable data,” Ramanathan told ThePrint.

At IIT Kanpur, the IKS centre is developing school-level curriculum materials rooted in Indian ethos. Arnab Bhattacharya, project coordinator of the centre, told ThePrint, “We are targeting school education because the newly introduced textbooks already include a significant amount of IKS content. But there is still a lot to be done. We’ve collected a large volume of material, and are now developing school-level resources—such as slides, examples, and practice questions—to enrich and support classroom teaching.”

He emphasised that the broader objective is to ensure IKS content can be taught effectively at multiple levels of education. “Whether it’s school, college, or graduate level, the idea is to create a robust base of materials—books, lecture slides, and other teaching aids—so that anyone who wants to teach IKS has everything they need. This is a crucial long-term effort. We need to move beyond the colonial framework of education, and IKS offers the ideal foundation for that,” he said.

Meanwhile, the centre at IIT Madras, established in 2022, focuses on four key areas: research into Indian scientific heritage, design of IKS-related courses, public outreach via social media, and training future scholars. The centre currently offers nine courses, covering topics such as Mathematics in India, Astronomy in India, Indian cultural studies, and Indian classical perspectives on clothing.

More Indian content in school textbooks

The National Curriculum Framework (NCF)—a key policy document that guides curriculum, textbooks, and teaching practices in Indian schools, released in 2023 under NEP 2020—recommended integrating IKS elements across subjects to foster student pride, and enhance learning by highlighting India’s rich intellectual and cultural heritage.

The National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) also formed a 19-member panel that year to ensure the incorporation in the new school textbooks being developed.

Between last year and this year, the new textbooks released by NCERT include more references to ancient Indian achievements and figures than ever before, besides references to Sanskrit terms. For example, the English textbooks for Classes 6 and 7 feature more poems and prose by Indian writers, along with increased references to Indian culture and heritage.

Michel Danino, a visiting professor at IIT Gandhinagar and chairperson of NCERT’s committee for drafting the new Social Science textbooks, noted that India’s traditional knowledge had long been underrepresented in school curricula, despite recommendations in the 1986 NEP and the 2005 National Curriculum Framework.

“This has led to an aberrant situation where generations of young Indians have the foggiest notions about Indian accomplishments in past or even recent times—and with the growth of the internet and social media, the vacuum gets filled up with the most fanciful or confused notions: more and more look for quick pride or sensation, with no solid foundations of genuine knowledge,” he told ThePrint.

Asked how this shift might benefit India’s education system in the long run, Danino said it may not be enough by itself to reform the education system, which suffers from deep pedagogical and structural flaws. “But it will hopefully awaken students’ interest, enrich their knowledge, and, without any sort of preaching, help sensitise them to the best values Indian ethos has stood for.”

The new textbooks have also begun referring to India as “Bharat”. For example, the Class 6 Social Science textbook released last year explains how “India, that is Bharat’’ had many names in the course of its history, and the names given by its ancient inhabitants include ‘Jambudvīpa’ and ‘Bhārata’. It says that foreign visitors to, or invaders of, India mostly adopted names derived from the Sindhu or Indus River, which resulted in names like ‘Hindu’, ‘Indoi’, and eventually ‘India’.

It also includes sections on Vedic schools of thought and stories from the Upanishads, among other elements of India’s intellectual heritage.

The Class 7 Science textbook released this year includes references to the ancient Ayurvedic text Charaka Samhita, explains how early Indian scholars predicted the monsoon by observing specific star patterns, and highlights the contributions of Indian scientists.

School principals, however, feel that adding Sanskrit terms to Science and Mathematics textbooks often creates confusion. “Students and teachers know these won’t be part of exams, so they don’t take them seriously. But highlighting Indian scientists and their contributions is a good idea,” said the principal of a Central Board of Secondary Education-affiliated school in Delhi, requesting anonymity.

Concerns over intent

A section of academics has voiced concerns over the growing emphasis on IKS in education, calling it “ideologically driven” rather than academically grounded.

Abha Dev Habib, associate professor at Delhi University’s Miranda House, said that the university has introduced courses, such as Vedic Mathematics, The Gita for Holistic Life, Leadership Excellence through the Gita, The Gita for a Sustainable Universe, in the name of value-added courses.

“IKS is nothing but an RSS-driven agenda. The courses being offered under it promote a single ideology, and a particular set of religious beliefs. Our curriculum used to be progressive, but things have changed significantly over the past few years,” she said.

Satyajit Rath, president of the All India Peoples Science Network, said that teaching about India’s ancient contributions is not inherently problematic, but the issue lies in how it is framed.

“It’s not wrong to teach about India’s historical achievements. What’s problematic is the ideological glorification that often accompanies it,” he told ThePrint, adding that the real concern is the intention.

“This idea that ‘our ancestors knew everything’ is flawed. No civilization’s ancestors knew more than what we know today. It’s not as if we were never taught about India’s contributions…We have always known that zero was an Indian invention, and that Aryabhata, Brahmagupta, or the Indus Valley Civilization made significant advances. What we weren’t taught—and shouldn’t be—is that our ancestors were somehow superior to everyone else. That should not be the purpose of this initiative,” he said.

“Therefore, all of this should be approached with rigorous and critical thinking. The contributions being highlighted are largely Vedic and Puranic, which represent only the Brahmanical tradition. Does that mean no one else contributed?”

Meanwhile, IKS national coordinator Murthy said that the division is actively engaging with various stakeholders to clarify misconceptions about the initiative.

“There is no place for animosity. The vast majority of people are not engaged with IKS from an ideological position,” he told ThePrint. “Many people now understand that we’re not asking anyone to go back and live as we did 2,000 years ago. All we are saying is—don’t discard the valuable knowledge from 2,000 years ago. People are gradually beginning to understand that.”

This is an updated version of the report.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Long before Op Sindoor, Marathas first carried out ‘surgical strike’. NCERT Class 8 book is proof