Gwalior: Four colourful buildings stand out on swathes of empty fields in Baraua village, 15 kilometres from Madhya Pradesh’s Gwalior city. Inside the unplanned campus, a worker bathes in the open with water from a hose pipe and buffaloes graze in the compound. The falling flex banners on two of the locked buildings suggest that these are hospitals.

The one building that is unlocked is called a nursing college, but it only has computer labs inside. The building is leased to a third party, which is using it as an examination centre for various competitive exams.

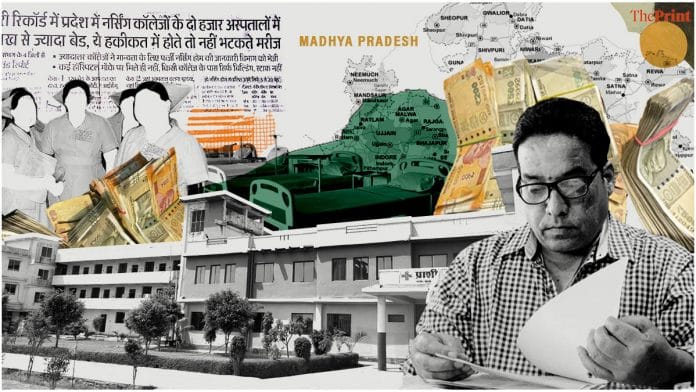

These abandoned buildings have made Gwalior’s primary school teacher Prashant Parmar a millionaire.

His private nursing and education colleges, which seem permanently shut, have allegedly sold bogus degrees to hundreds of students each year without holding any classes or giving them practical training in hospitals.

Parmar was raided last month by the Economic Offences Wing (EOW) for disproportionate assets. The investigators found jewellery worth Rs 65 lakh, a flat and two offices in the city’s posh locality Alkapuri, besides a private school and two marriage halls. Parmar drives SUVs, vacations in the US and Dubai, while his son and daughter study in expensive private universities.

Parmar, however, is just one among many owners of nursing colleges in Gwalior who have amassed unaccounted wealth, an investigation by ThePrint has found.

With 121 nursing colleges in 2021, Gwalior has become the hub for handing out nursing degrees to students mostly from Bihar, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. The neighbouring district of Morena has 30 nursing colleges, while Bhind has 18.

Even though these cheap private colleges are affiliated to state universities and have recognition from the apex body for nursing education, the Indian Nursing Council, students do not have to trouble themselves with entrance exams and the pressure of attending classes.

Many of these colleges, just like Parmar’s properties, only have locked buildings. They neither have permanent teachers nor doctors to work at the attached, functional hospitals, a mandatory requirement to open a nursing college.

Yet, they continue to issue nursing degrees each year. Armed with these legitimate degrees, the students, who hardly ever receive classroom or hospital training, get the licence to attend to real patients in government and private hospitals.

Also read: ‘Will college degrees carry same weight abroad as university’s?’ UGC reform norms find few takers

Covid an eye-opener

The inadequacies of Gwalior’s nursing colleges came to light when the district magistrate’s office asked them to set aside oxygen beds in their attached hospitals for Covid patients in preparation for the third wave of the pandemic.

According to Madhya Pradesh Nursing Shikshan Sansthan Manyata Niyam, 2018, all nursing colleges, irrespective of whether they are teaching bachelor’s or diploma courses, need to have a 100-bed hospital attached. Nursing is a regular course and a part of students’ training is conducted in hospitals by observing and assisting doctors.

When most such nursing colleges refused to set aside beds, the collector, Kaushlendra Vikram Singh, sent out four teams to inspect the facilities. They found empty buildings with no infrastructure or staff.

“The hospitals had beds but no one to look after patients. Doctors were on the rolls but were absent from the colleges. There was no equipment. The colleges had no students,” Singh tells ThePrint.

“One building we visited had four entrances and had put up boards of at least three hospitals besides other colleges,” said a member of the inspection team. “Many of the hospital buildings did not even have the space to keep 100 beds.”

On the ground, ThePrint can verify the findings of the official teams.

The highway to Baraua village is a stretch of barren farms on both sides. This vague address, “village and post Baraua”, is given for 13 colleges in the Indian Nursing Council’s list of private recognised nursing colleges for the year 2020-21 (the latest available).

The college buildings are constructed on open fields, with some not even surrounded by boundary walls. Parmar’s properties are also on the same highway, from where he allegedly runs two nursing colleges and two hospitals, besides two B.Ed. colleges. He allegedly has a stake in five other B.Ed. colleges which are run by his associates in Jharkhand.

A few metres away, GR Group of Education has its campus with a similar set up, multiple buildings, three colleges and one hospital on the same campus, with a guard keeping it all under lock and key. The hospital, the guard explains, was never functional.

Between these 13 nursing colleges which cover two villages, Baraua and Rairu, there should be 1,300 hospital beds. But there are none.

“These buildings have beds where you can just go and lay down to sleep. This is no hospital in this area. Those who were sick during Covid-19 had to go to Gwalior hospitals,” says Kanchan Singh, a resident of Baraua village.

Shivpuri Link Road, 10 kilometres from Gwalior, has another cluster of 11 nursing colleges. The turn towards these colleges is hard to miss with walls covered with these colleges’ advertisements.

On the huge campus of Ansh Group of Colleges, the hospital building is brand new. “The management spent over Rs 2 lakh to stock it with beds and oxygen cylinders after a strict order to upgrade by the collector’s office, but there is no trace of a patient yet,” says college administrator, Manoj Sharma.

“If the government orders nursing colleges to create such big hospitals, they should also arrange to send patients,” he adds.

This is, however, not the first time that these ghost nursing colleges have captured the attention of the district administration. In 2015, then-district magistrate P. Narahari acted on complaints which reached him through nursing students and managed to get some such colleges shut.

“The hospitals did not have minimum infrastructure; classes were not being conducted and teachers were absent. Some colleges did not even have rooms,” Narahari, now with the MP government’s MSME Department in Bhopal, tells ThePrint.

Seven years later, hordes of students still enrol in these locked buildings called nursing colleges.

Also read: Indian Nursing Council files police complaint over textbook justifying dowry, alleges defamation

How do these abandoned buildings make money?

Dejected with how his degree could only get him a job for a meagre salary of Rs 12,000 a month, a 24-year-old computer engineer from Bihar left his post at a multinational company in Chennai and enrolled in a GNM (General Nursing and Midwifery) course in a private nursing college in Gwalior.

“The job of a nurse will fetch me Rs 35,000 a month in Bihar,” says the man, who came from Patna to Gwalior to write his first-year exams.

Like most other students studying nursing here, the computer engineer found this private college through an agent in Patna. Not attending classes in Gwalior was part of the Rs 2 lakh package to get the nursing degree at the end of two years.

“The demand for nursing is high in Bihar, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh as these states keep opening vacancies in government hospitals. But the colleges in these states charge more than Rs 6 lakh for the GNM course, which can be done in Rs 2 lakh from Gwalior,” says Ashish Chaturvedi, a Gwalior-based health activist.

An informal network of agents then brings together the bogus colleges in Gwalior and the students in need of cheap, short-term degree and diploma courses, which will get them entry into government jobs. They buy seats in the private colleges and sell them to students for a commission.

“During exam time, the agents bring the students in groups, and hotels in Gwalior are full. Food is cooked on a mass scale on the hotel lawns, because so many students come to give exams here,” says Chaturvedi.

Back in their home towns, to experience working in a hospital, the students take up work in private hospitals assisting doctors.

A nineteen-year-old man enrolled at one of these colleges, who also wishes to remain anonymous, is confident that once he has a nursing degree, he will be given a red-carpet invitation by hospitals back home in Bihar which are starved of staff. Plus, a government job will provide him the security which private jobs won’t.

To ace his skills, he adds, he has already started work with a cardiologist in a private hospital in Patna. “I give injections to patients in the ICU,” he says proudly. “What would one learn sitting in classrooms here anyway? The colleges don’t have teachers.”

The fact that so many students are enrolled in one district itself should have raised red flags.

According to Indian Nursing Council norms, a college with 40 diploma-level GNM seats should have 10 teachers and four other staff. The norms are higher for B.Sc. Nursing courses. The hospital attached should have at least 75 per cent bed occupancy. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that for 121 nursing colleges, Gwalior should have more than 1,200 nursing teachers.

The district administration is well aware of this huge gap in healthcare human resource. The data from the chief medical health officer (CMHO) shows that only seven nursing colleges in Gwalior have a functional 100-bed hospital.

Despite the glaring gaps, not even a single nursing college or its attached hospital faced any interrogation from inspection teams at the time of awarding approvals.

“For registration, the hospitals show that they have everything. They have beds, infrastructure and they even get patients. For things that they can’t show, they give us receipts that those things are in process,” says Manish Sharma, the CMHO.

But the CMHO could not explain how facilities could deteriorate soon after registration.

“When the basic norms were missing, then it was obvious that the initial inspections to get approvals for running the colleges and hospitals were manipulated,” says a member of the collector’s team, who inspected hospitals attached with Gwalior nursing colleges.

“The inspection teams are easily managed and corruption is so stark that even the good colleges do not speak against it. If they do, the teams may give them a negative report,” adds one college administrator who wishes to remain anonymous, claiming he shut the nursing course in his college because of this corruption.

The CMHO admits that the inspection teams have been manipulated before, but there were no police complaints registered against them. The members were simply moved from one team to another. The routine surprise inspections of the hospitals and colleges are also missing.

In 2021, a PIL was filed with the Gwalior Bench of the Madhya Pradesh High Court by advocate Umesh Bohra, asking the court to set up independent teams to inspect all nursing colleges in the Gwalior-Chambal region, which covers nine districts.

Private Nursing Institute Association All India intervened in the case and managed to get a stay from the Supreme Court on the high court order of inspection by a team of lawyers. The case is now back to the high court and the council inspection teams are back to inspecting colleges, which they gave approvals to earlier.

“It is wrong to say that the inspection teams are managed by the nursing colleges. The association has received no such complaint. One or two colleges may be corrupt, but this affects the credibility of all colleges,” says R.M. Singh, president of the association.

The need for beds for Covid-19 cases and the pressure by the collector’s office, however, did manage to get the licences of about 55 hospitals, which were attached to nursing colleges, cancelled in the last six months.

Collector Singh is confident that he will clean the system in the next two years. “We are getting institutions up to the mark,” he says.

The Madhya Pradesh Nurses Registration Council, the body that gives final approvals to nursing colleges, did not respond to queries by ThePrint.

Selling seats, risking lives

The moving of files from the collector’s office to the council and the CMHO, and the raids by the EOW have, however, not dented the solid ecosystem of Gwalior’s nursing colleges.

Waiting outside an examination centre for his wife, a nursing student in Gwalior Nursing College, Sandeep Kumar offers to help ThePrint’s reporter find a seat in a college. He spoke to his agent, a teacher at one of the colleges, and offered a seat in the batch of 2021-22.

“The seats of Gwalior Nursing College are full for 2021, but two-three other colleges have vacant seats. You will get the degree in 2024. But you will have to tell me soon. Otherwise, you can get admission in Gwalior Nursing College’s 2022 batch,” he says.

Gwalior Nursing College is among the 14 colleges whose registration was cancelled after the action by the collector.

And so, it is obvious that before the case concludes in the high court and the INC inspects colleges, many untrained students like the ones mentioned above could enter the healthcare workforce, leaving patients exposed to medical negligence and a lack of accountability.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also read: Development, good governance meaningless without mobilising basic facilities: Madhya Pradesh CM