Guwahati: Halting his performance midway during a live concert in Upper Assam’s Sivasagar, singer Zubeen Garg once turned to the crowd with a playful question.

“You have been saying ‘Zubeen, Zubeen’ for over three decades. But do you even know what Zubeen means? Don’t Google it,” he said. The audience responded almost instinctively. “It means love!” they shouted back in unison. Zubeen smiled, visibly moved.

Then, in his characteristic style, he leaned into the mic and explained, “I understand that. But it’s actually a Persian word. It means a talwar, a spear.” That evening, the crowd may not have known what ‘Zubeen’ meant. But they had no doubt what Zubeen meant to them. And three weeks after his passing, the world knows too.

A cultural colossus, Zubeen’s death at the age of 52 in Singapore, under circumstances now the subject of a high-profile investigation, has wrapped Assam in a grief it is still struggling to shake off.

Local TV and radio stations continue to play Garg’s songs on loop. The lyrical prose of Mayabini Raatir Bukut (in the magical night’s embrace), which Garg once said he wanted people to sing after his death, continues to rise into the night sky like a hymn from neighbourhood memorials.

Crowds still gather at his houses in Guwahati’s Kharguli and Kahilipara localities.

But nowhere is this grief more palpable than at Kamarkuchi, a patch of land off National Highway 27 on the outskirts of Guwahati, where Garg was cremated on 23 September in the presence of thousands. The site has turned into a shrine, drawing people from near and far, around the clock. Even as construction has begun to turn it into a permanent memorial, the lack of infrastructure has not deterred the steady stream of mourners.

Every hour, hundreds arrive, young and old, college couples and retirees, Hindus and Muslims. Some pray silently in front of his portrait, lighting lamps and candles in his memory; others chant “Joy Zubeen Da!” Many quietly weep.

If Yagneswari Kakoti, a septuagenarian who listened to Garg’s rendition of borgeets— Assamese devotional songs composed by the 16th-century saint Srimanta Sankardeva—is present at the site, so is Mohammed Rohit Ali, who grew up listening to Garg’s chartbusters.

“Garg is God, and this is his temple,” said Kakoti, struggling to hold back emotions as Naamkirtan, taking place under a tent next to the spot where Garg’s pyre was lit, filled the air.

“You come here at three in the night and you will find the same number of people, if not more,” said Tarun Konwar, a member of the Assam Police posted at the site for crowd management.

Also Read: Assamese social media on a hunt for culprits. ‘Exploited Zubeen da for years and killed him’

‘I am free, I am Kanchenjunga’

What explains this magnetic pull towards an artist whose life and work defied easy definition?

Born in Meghalaya’s Tura to Mohini Borthakur and Ily Borthakur, Zubeen grew up in various parts of Assam owing to his father’s transferable job as a magistrate in the Assam Civil Services. His father also wrote poetry under the pen name Kapil Thakur, while his mother was a singer.

‘Garg’ was the family’s gotra name, one that Zubeen chose to use in place of his Brahmin caste surname. Later, he would famously proclaim: “Mor kono jaati nai, mor kono dharma nai, mor kono bhagawan nai. Moi mukto, moi Kanchenjunga” (I don’t have any caste, I don’t have any religion, I don’t have any God. I am free, I am Kanchenjunga).

Palmee Borthakur, Zubeen’s younger sister and a professor at a private university in Guwahati, told ThePrint that he was never formally trained as a singer but became one by listening. Another sister, Jonki, who was also a singer, died in a road accident in 2002.

“Our mother was into music, dance and drama. She was an artist, and she wanted all of us to be engaged in the arts,” Palmee said.

“Initially, he learnt the tabla and my sister was learning Kathak. My father had great taste in both Indian and Western music. He used to bring home all the latest records. He introduced us to different genres. Zubeen learnt some folk music from a teacher in high school, but everything else he picked up by listening, learning and interacting,” she added.

With time, the boy who had never been formally trained in singing went on to amass a vast repertoire as a singer, lyricist and composer across more than 40 languages. His rise began with the runaway success of his first Assamese album, Anamika, released in 1992.

Borgeet to Bollywood

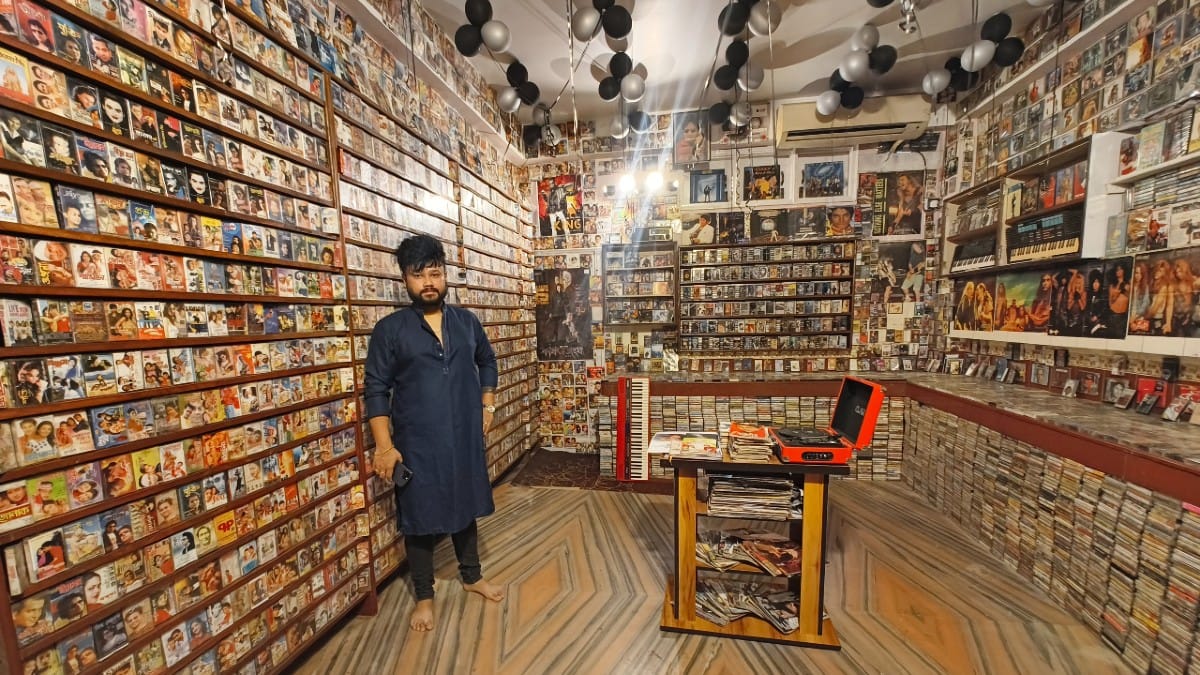

Three days before his death, Garg inaugurated a private music library in Guwahati curated by Vishal Kalita, 30, a longtime fan. It now stores much of his musical legacy.

Located in Kalita’s home in the city’s Hatigaon neighbourhood, the library houses a rare and exhaustive collection of audio cassettes and CDs, formats long phased out in the digital age, all featuring Garg’s work. The archive has been painstakingly compiled over two decades from across India.

“I started collecting when I was in school, back in 1999. The idea of an archive came to me in 2016. When I told him about it, he encouraged me and eventually inaugurated it on 16 September, just three days before he died. That day, when he saw the collection, he turned nostalgic,” said Kalita.

Kalita spared no effort in building the archive, including, at one point, paying Rs 25,000 for a cassette of a long-forgotten album that featured one of Garg’s songs.

While it wasn’t his first Hindi song, it was the 2006 hit Ya Ali that marked Garg’s true breakthrough in Bollywood. Another track from the same year, Jaane Kya, also gained popularity, helping him establish a foothold in Mumbai while simultaneously seeing a surge in his popularity in the Bengali film industry. He even bought a house in Mumbai, its doors always open to artists from Assam struggling to find their footing in the film capital.

But his heart remained firmly in Assam and the Northeast, prompting him to make Guwahati his permanent base, even as he continued to lend his voice to Hindi songs from time to time.

“He was that much in love with his people. He was madly in love with the Northeast. That’s why maybe he left Mumbai and came back,” Garima Saikia Garg, the singer’s wife, told ThePrint.

Garg often remarked in his interviews that he believed that a “king should never leave his kingdom”.

Also Read: ‘I am Assam,’ Zubeen Garg had said. He was the soundtrack to our lives

Music born out of upheaval

When Garg burst onto the Assamese musical firmament, the state was in the throes of intense upheaval. The Indian state was locked in a bloody conflict with the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), a militant outfit demanding secession from India. For much of Assam’s youth, the future looked uncertain and dim.

Enter Zubeen Garg, modern Assam’s rebel minstrel. With a bewitching blend of lyrical poetry and mellifluous vocals, he swept an entire generation off its feet. And all of a sudden, the future did not seem entirely hopeless after all.

“He came and sang in a style that challenged the conventional way of Assamese music. His early lyrics had shades of Chester Bennington of Linkin Park, laced with an innate sense of sadness and melancholia. He spoke about hope and love, too, but in his sense of love, there was always loss and longing. People found shelter in the absurdity of his music and lyrics,” said Rahul Gautam Sharma, a protégé of Garg.

Sharma first met Garg after the latter was impressed by a critique he had written of Garg’s songs as a student who had just cleared Class 10. Over time, Garg groomed him into a singer, composer and film writer. Sharma is the writer of ‘Roi Roi Binale’, Garg’s last Assamese movie as an actor and singer, which is scheduled to be released on 31 October.

Filmmaker Maanash Barua, son of the late director Munin Barua, recalled how Garg introduced Assamese audiences to a kind of full-throated, high-pitched singing they had not heard before—a sharp departure from the tone and style of earlier stalwarts who had shaped the previous generation’s musical sensibilities.

“People who were into Axl Rose of Guns N’ Roses, Steven Tyler of Aerosmith or Kurt Cobain instantly connected with Zubeen’s songs,” said Barua, who shared a deep bond with Garg over music, movies and whisky for more than two decades.

It was during one such late-night reverie, with drinks flowing and conversation meandering, that Mayabini Ratir Bukut was born. “Zubeen always said he could only focus at night; that was his silence,” recalled Barua. “He believed the moon gave him his energy.”

One night in 2001, in a sudden creative spark while they were drinking, Garg scribbled the lyrics of Mayabini onto the foil of a cigarette pack and handed it to Barua for safekeeping. But by the next day, the trousers Barua had tucked the foil into had gone through the laundry. The lyrics were gone.

Between them, only fragments survived. Zubeen remembered the opening line, and Barua one more: Dhumuhaar xote mur bohu jugore nason (“my waltz with these storms has played out for ages”).

When they met again and Barua broke the news, Garg fixed himself a drink, picked up a blank sheet of paper and began writing a new version of the song, which he went on to record later that night.

Zubeen Garg rattled political class

Garg called himself apolitical. However, over the years, he made one move after another that rattled the state’s political class and angered conservative sections of society. Yet, with every such act, his popularity soared.

He publicly renounced the sacred thread; opposed animal sacrifice at the Kamakhya temple; defied ULFA’s diktat against singing Hindi songs at Bihu functions; said Krishna should not be regarded as God but as a man; advised athlete Hima Das to eat beef; and remarked that the Centre had not done Assamese any favour by giving it the status of a classical language.

He often mocked powerful politicians at his concerts, opposed developmental works at the cost of ecological destruction, and led a stormy movement against the Citizenship Amendment Act. In interviews, he often described himself as “half-Bengali”, a strikingly bold assertion in a state long riven by identity politics. In private, Garg expressed dismay over the politics of polarisation and the dictatorial traits displayed by those in power.

“We had conversations about how Prime Minister Narendra Modi or Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma behave. He did not like the idea of control, of a big brother,” said Sharma. Garg called himself a socialist and was influenced by progressive artists such as Assamese communist poet Hiren Bhattacharya.

At the height of the protests against the CAA in Assam, Garg penned and sang Politics Nokoribo Bondhu, warning the political class against playing with people’s sentiments attached to Jaati and Maati. He later alleged the BJP government posthumously conferred the Bharat Ratna on Bhupen Hazarika in 2019 to quell anger against CAA in the state.

“He was the voice of the common people, who often have strong views on societal and cultural norms but are afraid to speak out. He was so strongly connected to the people of Assam that he had become their voice. He was also misunderstood so many times by the same people who are now shattered,” said Barua.

Garg also acted, directed and produced movies that made record business in Assam, helping revive the local film industry.

Also Read: ‘Processing the loss’—At Delhi pub, ‘Joi Zubeen da’ chants, 1 am singing

Rooted in Assamese consciousness

Artistic genius aside, it was Garg’s unassuming, non-performative rootedness that truly set him apart, earning him a place not just in the hearts but in the everyday consciousness of the average Assamese. It also helps explain the vast, near-Himalayan wave of mourning that swept the state after his passing.

Why else would Indra Bardoloi, who runs a small eatery selling poori-sabzi near Garg’s Kahilipara residence, tonsure his head for the singer’s cremation?

“He unexpectedly visited my shop one day, though his preferred shack was another one located nearby,” said Bardoloi, who distributed water to mourners for days on end as people flocked to the area to pay their last respects to the singer.

It was not unusual to see Garg quietly slipping a few thousand rupees to someone in need. He was often spotted at modest roadside eateries, perched on rickety benches, sharing a simple meal and hearty laughs with rickshaw pullers and daily wage labourers.

He famously rescued a girl who was facing sexual abuse while working as a domestic help, and assisted her legally till the accused was convicted in a lower court.

Even when someone had not been directly touched by Garg’s generosity, they would invariably know someone in their immediate circle who had.

For instance, Miftaharul Zaman, who stood quietly in front of Garg’s garlanded portrait at Kamarkuchi one recent evening, recounted how Garg went out of his way to help a person in his village who needed urgent kidney surgery.

Investigation into Zubeen Garg’s death

The clamour for a thorough investigation into his death, meanwhile, is reaching a crescendo. On Saturday, an emotional Garima Saikia Garg visited his memorial and prayed as hundreds gathered around her. She appealed to people to flood social media with the hashtag “JusticeForZubeen”, and the crowd roared in approval.

On Monday, she posted on social media, “We need justice for Zubeen Garg within 10 days.”

Public anger has also begun spawning new controversies. One man arrived at the memorial and snapped his sacred thread in front of television cameras and recording mobile phones, declaring that from now on his only identity would be that of a human being, as he called on others to rise above caste and religious divisions.

Assam minister Pijush Hazarika, a close aide of CM Sarma, reacted to the incident by saying that while Garg would receive justice, the act of breaking the sacred thread was against Sanatan Dharma. His statement drew a backlash from a section of Assamese people, with many urging him not to frame an emotional outburst in religious terms.

Akhil Ranjan Dutta, professor of political science at Gauhati University, offered a sociological explanation for the mourning and anger triggered by Garg’s death.

“Top artists like Bhupen Hazarika, Khagen Mahanta, Jayanta Hazarika and Birendranath Datta had a collective safety net in the Indian People’s Theatre Association and in the political environment of that era. Zubeen, on the other hand, single-handedly filled a void in a dark time marked by immense economic backwardness. He did not have such a safety net, which seems to have led to his exploitation by certain sections of people,” he said.

“While Zubeen sang to deliver hope and joy to the masses, people somehow failed to feel his anxieties and agony. After his death and the mysterious circumstances surrounding it, they have realised it. And that is what is triggering public anger today,” he added.

Garima Saikia Garg’s reflections, in conversation with ThePrint, echoed this analysis.

She said decades of relentless work and a punishing schedule had finally taken their toll on the singer over the last two to three years. He frequently spoke of feeling exhausted and of an underlying sense of emptiness.

As Garg told writer Rita Chowdhury in his last-ever podcast interview, recorded just before he left for Singapore: “I am not a machine, come on … people made me a machine, I was not like that. I want to see how many of them would still be there when I grow old. When a fighter dies in a war, only three or four people stay; the rest run away.”

In mourning him, Assam may also be seeking forgiveness from its king, the one who has left his kingdom forever.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Zubeen Garg saga is resembling Sushant Singh Rajput. Did we not learn our lesson?