Chhainsa (Palwal, Haryana): Around 10 am, as the February sunlight begins to hit hard, a group of men in Chhainsa, a village in the Palwal district of Haryana, sit in a tight circle around a hookah, discussing a mystery that has gripped the village—a string of sudden deaths that no one here can explain.

In the middle is Haqimuddin, whose 24-year-old son Dilshad walked to the hospital with fever and died of liver failure just two days later on 11 February.

Haqimuddin had first taken Dilshad to a local doctor. When the fever did not subside, the family rushed him to a private hospital in nearby Hathin town, where doctors advised further tests. The reports suggested jaundice.

From Hathin, they took him to a government hospital in neighbouring Nuh district. “My son walked to the hospital on his own,” Haqimuddin recalls. Within 48 hours, Dilshad was declared dead.

“He was not that serious. Kaise 48 ghante mein sab khatam ho gaya? (How can it all end in just 48 hours?)” he asked.

Dilshad’s is not an isolated tragedy.

In this village of over 10,000 people, deaths have come in a cluster over the past month—sudden, and unexplained. Children as young as 13 and 18 have died of acute liver failure within just 24 to 48 hours of getting a fever. Authorities confirm seven deaths in the village, four of them children below 15 years of age. Villagers, however, claim as many as 20-22 deaths in the past 20 days.

All the families ThePrint spoke to describe a similar pattern: Fever and stomach ache, a quick referral, rapid deterioration and death.

A few lanes from Haqimuddin’s house, Mohammad Shakir points to the charpai where his 14-year-old son used to sleep. The boy fell ill on 26 January.

“My son was absolutely fit,” Shakir said. After he complained of fever and stomach ache, an ultrasound was done to confirm swelling in the liver and fluid in the abdomen. “Ladka apne pairon par gaadi mein baitha (the boy sat in the car on his own),” Shakir said. Within 20 hours of hospitalisation, he was gone.

“How can the liver of a 14-year-old child fail in just 24 hours?” he asked, voice breaking. “Itna chhota bachha (such a small child).”

Shakir blames contaminated water for his son’s death. “Our village doesn’t have safe drinking water. Our fields are filled with stagnant water because there is no exit,” he said.

As the village does not have its own clean drinking water source, residents depend on either paid tanker supplies or piped water. Health officials suspect that the villagers often store water for extended periods, which can heighten contamination risks.

In the fields around the village, blackish, stagnant water collects in puddles. Villagers say that the water pipelines that pass through these fields have leakages and hence, the piped water gets contaminated. This water is also used for drinking and bathing purposes.

“When the Delhi–Mumbai expressway was constructed, the problem of water stagnation began. This has persisted over the past four to five years. Since then, we have taken several corrective measures, including laying pipelines to facilitate drainage. Earlier, nearly 4,000 acres were waterlogged, that has now reduced to around 1,200 acres,” Harish Kumar Vashisth, Deputy Commissioner of Palwal told ThePrint.

Contaminated water

A total of 31 water samples have been collected from different sources in the village so far. Officials said the main drinking water sources, like water from the tankers, showed no major issues. However, six samples showed bacterial contamination due to poor storage and hygiene.

Villagers at Chhainsa told ThePrint the issue of contaminated water is not a recent phenomenon. They said they have complained to the district administration several times in the past to address the problem but their pleas have fallen on deaf ears.

While villagers say the deaths occurred over a month, according to District Medical Officer Dr Satinder Vashishth, the deaths occurred between 31 January and 11 February.

“Not all (deaths) were Hepatitis B. Only four were Hepatitis B positive. We do not yet know the exact cause of death. We are collaborating with our medical college team and tracking records and patient histories to determine the cause,” Dr Vashishth told ThePrint.

“Hepatitis B or C does not usually cause sudden deaths, so there may be some other superimposed reason. We are investigating that,” she added.

“Water tankers are being chlorinated, and chlorine tablets are being distributed. We are conducting health education activities, advising people to drink clean water and maintain hygiene. The situation is under control and there is no need to panic,” Dr Vashishth said.

She also said that the administration was informed about some quacks practising in the village, and authorities suspect they may have used infected medical equipment, which would explain the Hepatitis B and C. “When our team visited, their establishments were closed. We have informed the police to trace them. Villagers have been advised not to seek treatment from unqualified practitioners,” she said.

Dr Vashishth admitted that Chhainsa village has a problem of stagnant water in the fields, which is largely due to poor drainage and the presence of fishery ponds. While residents do not drink this water, she indicated that stagnation can indirectly raise health risks by increasing the chances of contamination in surrounding areas.

Government gropes in the dark

A rapid response team reached the village on 1 February and health camps started on 2 February.

Unable to definitively establish the cause of the recent deaths, local authorities are investigating several possibilities, including contaminated drinking water, stagnant water sources, contaminated piped water, and the negligence of unlicenced medical practitioners.

While these factors are under suspicion, a direct link to the fatalities and the confirmed cases of Hepatitis A, B, or C has not yet been established. Nevertheless, medical teams are testing villagers for Hepatitis B, C and HIV.

HIV tests are being carried out as HIV is transmitted the same way Hepatitis B and C are—infected blood, sexual contact, sharing needles, or from mother to child during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding.

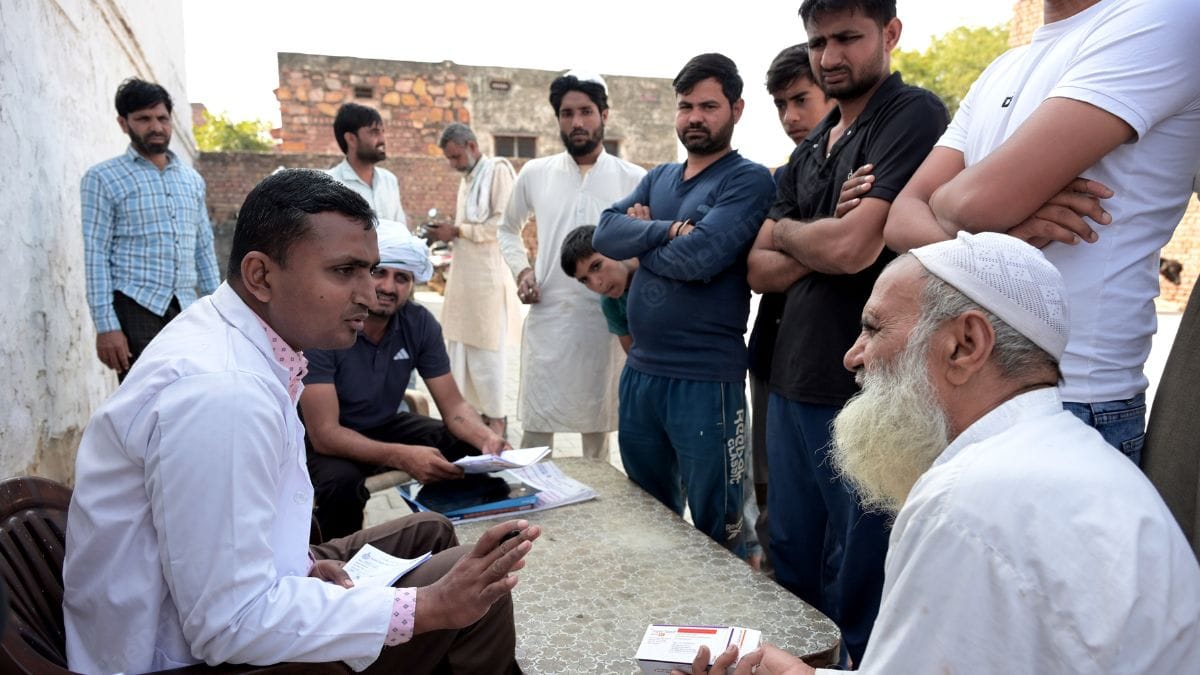

“We are testing people for Hepatitis B, C and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). So far, around 150 people have been screened today in this camp. Most reports are normal, with one or two (Hepatitis B and C) positive cases,” said Sunil Kumar, a CHO overseeing one of the health camps.

The district administration has set up three temporary medical camps in the village. Folding tables stand in a row outside the village Sarpanch’s house. Masked healthcare workers including doctors, community health officers (CHO), lab technicians, auxiliary nurse midwives (ANM) and accredited social health activists (ASHA) are on duty from 9 am to 5 pm.

On 16 February, the Centre also dispatched teams from the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) to Palwal.

Dr Ranjan Das, Director at NCDC told ThePrint, “We are investigating. Our team had been there the day before yesterday (16 February). Yesterday also, a team of microbiologists was sent. They will be submitting an interim report to the (health) ministry today,” he told ThePrint Wednesday.

‘Examining all angles’

The NCDC director said they are examining multiple angles. “Hepatitis B has several routes of transmission, and there could be other causes as well. It is like a police investigation—detailed and intensive. Multiple teams from different disciplines are involved. Each team will submit its individual report, which will then be compiled and forwarded to the Ministry of Health,” he added.

At the village camp, nurses in white coats sit behind stacks of blister packs, cough syrup bottles and brown cartons of medicines. Women with dupattas pulled over their heads wait with children. A government health van is parked on the edge of this arrangement, its doors open, supplies inside visible.

At one table, a staff member counts out tablets carefully, repeating dosage instructions twice. At another, blood samples are being collected.

At one of the camp tables, Priya has just been told that she has “Kaala Peeliya”—a term in northern India used for serious, chronic liver infections, specifically Hepatitis B and C.

“I had fever. I often get typhoid,” she said softly. “I got tested today. They told me it is jaundice. They said I will have to go to Palwal.”

One by one, villagers step forward with documents. Names are noted and details are recorded. The paperwork includes identification, test reports and vaccination history.

So far, over 2,000 people have been tested at these three camps in Chhainsa, and a total of 32 have tested positive for Hepatitis B and C. Of the 32 cases, three have Hepatitis B, and the remaining have Hepatitis C.

‘Our pleas have gone unheard’

Rameshwar Singh, a retired Army personnel and a resident of the village, flips through a thick file of petitions he says he has submitted to the local MLA, the chief minister, the deputy commissioner and others over the years.

“There is leakage in the water supply lines. Dirty drain water gets mixed with the drinking water. That is the same water we consume,” he said.

Mohammad Islam, the village sarpanch, said the death toll is higher than what the administration acknowledges. “In the last one month, around 20 to 22 people have died,” he claimed, pointing to what he says is a long-standing problem of water stagnation in the village.

“Our land has remained waterlogged for 15 years. We cannot grow crops. There is no proper facility for drinking water. We depend on tankers. I have written to the administration about all this,” he said.

No clarity on number of deaths

As the administration works to determine the cause of the deaths, questions remain over the actual toll. Some residents above the age of 75 have also died in recent weeks. However, since no direct link has been established between those deaths and the suspected infections, officials have excluded them from the count, terming them natural.

But stories like Naahid’s continue to disturb and raise questions.

Her 18-year-old daughter first complained of stomach pain. The next day, she developed a fever. By the time she was taken to the government hospital, they were told jaundice had severely damaged her liver.

“Even the doctors were saying—a liver that does not fail in 40 or 50 years, how did it get destroyed in such a young girl?” Naahid asked. “The doctors told us they did not know what disease it was.”

(Edited by Viny Mishra)

Also read: In Jammu’s Budhal, fear grips villagers in wake of 17 ‘mysterious deaths’ in 45 days