Bhubaneswar: A 16-year-old tribal student from Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences remembers the day horror unfolded in a dark, dingy room of his hostel two years ago. Along with three other boys, he was pulled into a storeroom by four teachers and beaten black and blue with water pipes, sticks, and even kicked around. This was his ‘punishment’ for trying to break up a fight, he claimed.

“You Adivasi people from jungli areas. We have given you everything: food, shelter, education. Instead of being grateful, this is how you behave!” The student, now in Class XII, recalled his teachers yelling at him as they cast blow after blow. This student from Koraput, a tribal district in south Odisha, has been a student of Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences in Bhubaneswar since Class I.

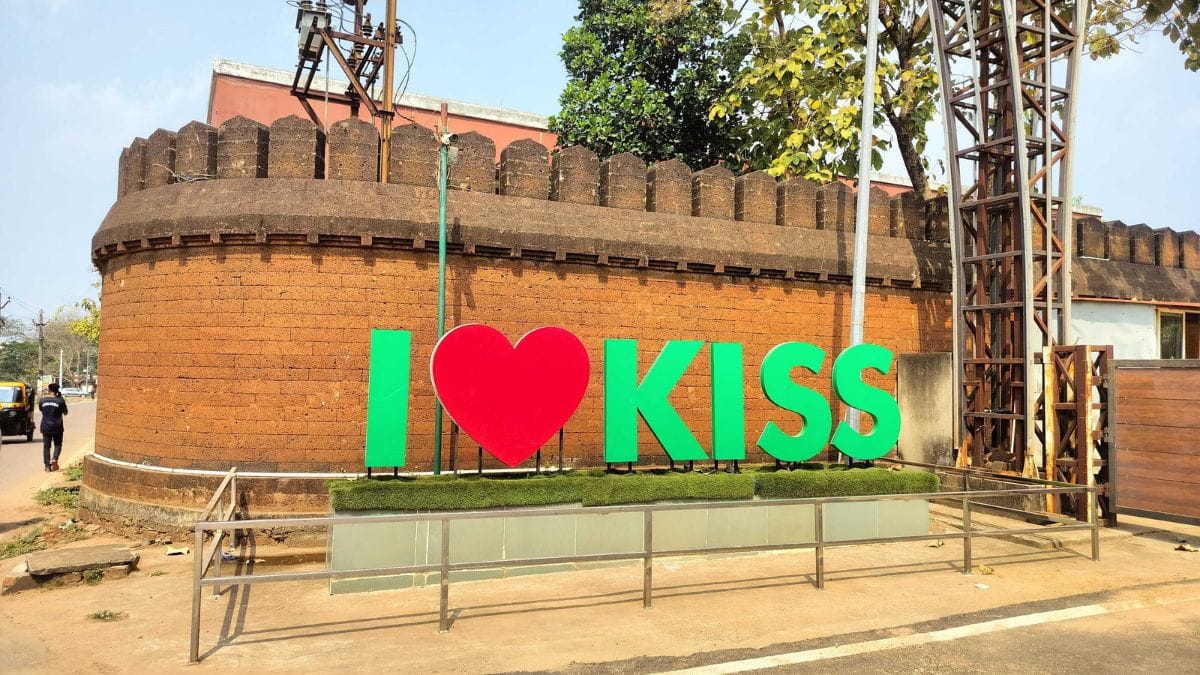

The Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS) is situated right next to the Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology (KIIT), where an alleged suicide of a student from Nepal and the mishandling of the resulting protest led to a diplomatic row. On 1 May, another Nepali student died by suicide. This was the second suicide on campus in three months. A leaked KIIT faculty video boasting how the institution feeds 40,000 students for free only added fuel to the raging controversy in February. Of these 40,000 students, 30,000 are part of KISS—a residential education hub for underprivileged tribal children, many of whom come from Odisha’s Naxal-affected areas. The Child Welfare Committee (CWC) in 2017, and most recently the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in February this year, have noted the poor living conditions of tribal children in the school. Both these reports were stayed in separate interim orders by the Orissa High Court.

The school was visited by a team of NHRC investigating allegations made in a complaint filed on 28 February, citing an earlier CWC report on allegations of poor living conditions at KISS. A team of SSP Bhubaneswar, registrar law division, and an inspector-ranked officer carried out a spot search on the campus and concluded that conditions of overcrowding, lack of ventilation, and toilets continue to persist on the campus.

The NHRC in 2025 also directed the formation of a joint committee in Kordha’s district magistrate’s office to investigate allegations further. However, KISS approached the Odisha High Court and got the order stayed.

KIIT and KISS argued that the principles of natural justice had been violated, as they did not receive a copy of the report from the investigating team prior to the issuance of orders for further investigation by the NHRC.

“Although the officials of the National Human Rights Commission undertook an inquiry and subsequently prepared a report, neither the said report nor its findings were made available to the authorities of the Petitioners’ Institution before the issuance of the impugned order dated 27.03.2025. Such omission, it is contended, constitutes a clear breach of the principles of natural justice and stands in violation of the statutory safeguards embodied under Section 16 of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993,” the petitioners, KIIT and KISS, argued.

Granting relief, the court passed an interim order staying further proceedings by NHRC in the matter, as well as NHRC’s orders directing further actions or investigations by government authorities.

Tribal children from other states also study here. KISS, founded by former MP Achyuta Samanta, began in 1992 with the lofty goal of uplifting tribal children from the pits of poverty and introducing them to a better life. It began in a rented house with 125 children, but by 2005, the institute’s strength had increased to 3,000.

And while it has impacted many lives over the past three decades, there have also been numerous allegations against the institute—from missing children and corporal punishments to crammed dormitories with fewer fans where students face breathing difficulties in summer.

“The kids have been indoctrinated, and often lose their sense of self-confidence and respect at KISS,” said a former teacher.

KISS offers thousands of tribal students a shot at mainstream education, competitive exams, and professional jobs. Former students have gone on to become lawyers, engineers, and doctors. ThePrint spoke to former teachers, alumni, current students, and parents to understand the truth behind the allegations made against the “largest indigenous school in the country” proudly calling itself the “world’s ‘largest anthropology laboratory”.

ThePrint reached the director, CEO of KISS, repeatedly via emails, and the communication director and Achutya Samanta via WhatsApp messages and calls. We’re yet to receive a response.

World’s largest indigenous school

“Since I can’t afford to send them to faraway schools, I am hopeful they will get a good education here,” father of a tribal student.

On a Monday morning in February, tens of Adivasi families walked in and out of the 16-acre KISS campus. Others hovered anxiously in front of the communications office, waiting for their children to come out or for news about their admission application.

“I am here to get my child admission in the school as there are no schools near my village,” said a father from Koraput district, who was accompanied by his two daughters, 10 and 12 years old. “Food and lodging are free. Since I can’t afford to send them to faraway schools, I am hopeful they will get a good education here.”

As they waited in anticipation, they watched students moving from one class to another in a single file, guided by their teachers who wore cream coloured sambalpuri sarees. ThePrint was not allowed inside the campus beyond this point.

The campus currently has five hostels—three for girls and four for boys. There’s a sports complex, an archery ground, a swimming pool, as well as an athlete stadium.

“Our students have participated and won laurels in the Olympics, ASIAD, South Asian Federation Games, Commonwealth Games, and other international and national events of prominence.”

On its website, the organisation says it puts a special focus on sports for tribal children. In 2007, the KISS boys’ rugby team became Under-13 world champions. The institute lists 28 sports in which training is provided, including boxing, yoga, archery, kho-kho, and hockey. And it claims to employ more than 250 sports staff.

“Right from the inception of Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology (KIIT) and Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS), I tried to emphasise on sports even though we were primarily building academic universities. With our dedicated efforts at Empowerment through Sports from 2005, I have made the Sports Department and Wing a high-rise mountain (When I say mountain, I really mean it),” a message from the university’s founder, Achutya Samanta, read. It goes on to say that no other university has been able to produce sportspersons of the calibre that KIIT and KISS have.

“Our students have participated and won laurels in the Olympics, ASIAD, South Asian Federation Games, Commonwealth Games, and other international and national events of prominence.”

The university regularly engages in international meets and conferences. When ThePrint visited the institute in late February, it was welcoming delegates from Japan’s Doshisha University for a conference. In 2023, greeted by dancing students and a gigantic assemblage of KISS students, former Odisha Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik visited the university to inaugurate a new campus for higher studies.

In 2018, students had ‘celebrated’ the birthday of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, where they sang Happy Birthday, watched a movie dedicated to the Prime Minister, and even made paintings for him.

For parents like the father from the Koraput district, these are a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But at the same time, KISS has also been denounced as a ‘factory school’ by its critics.

“For us tribal students, KISS is not just a school or an institution. It is our home, our family, our only hope. It has given us everything–education, food, clothing, dignity, and most importantly, the right to dream. Many of us come from the remotest villages, where survival itself was a struggle. KISS gave us the chance to live like every other child of this country, with self-respect and opportunities,” the KISS Students Association, alumni association, and parents association said in a joint statement.

In 2020, activists and academics in India, such as Verginius Xaxa and Nicholas Barla, and Nandini Sunder, had written an open letter, calling on the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences (IUAES), Indian Anthropological Association and World Council of Anthropologists (IAA), against hosting the conference at KISS. The backlash was swift, and KISS was dropped as a venue for the 2023 World Anthropology Congress.

Unfazed, the management organised a conference of its own that very year, under the banner of the United India Anthropology Forum. The five-day event was attended by 1,100 anthropologists from 51 nations, KISS claimed.

Behind the international recognition, global conferences, and sports awards, students and alumni allege that the living conditions are abysmal, marked by a lack of dignity, corporal punishment, isolation, and abuse. Over the years, many students have allegedly tried to run away. It even came under scrutiny by the District Child Welfare Committee, but their report did little to improve the condition of tribal children.

Also read: Fire in the Aravallis. Waste burning in Haryana is causing lung infection, rashes, nausea

Cut off from parents in a ‘jail’

The Class XII student remembers getting into a tempo traveller along with his parents and five other families from his village before he started on a 12-hour arduous journey to KISS 11 years ago. He described his experience as a “jail”, a “chicken coup”. But he kept coming back after every summer break for one thing: the prospect of a better future.

The teenager from Koraput has spent the better part of his academic life sharing a dormitory with almost 150 other students. The three-tier bunk beds are lined right up to the ceiling, with no breathing space between the beds.

“It gets difficult to breathe there, especially in summer.”

“There are fans pinned to the wall, but only a handful, which are not enough for such big dormitories. Those in the second or the lowest bunk do not get air, it gets suffocating, especially in peak summers,” the student recalled.

As many as four students corroborated these living conditions.

“The bed is as tall as the ceiling, so on the top bunk one cannot sit straight,” said another student from Nabrangpur district. “It gets difficult to breathe there, especially in summer.” The temperature in Bhubaneswar crosses 40 degrees Celsius in the summers.

The spot inspection by NHRC confirms the poor living conditions, which were first highlighted by a 2017 Child Welfare Committee investigation. “A 2017 CWC report revealed poor living conditions at Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences, including overcrowding, unclean facilities, and lack of basic amenities,” the NHRC report reads. “It is noticed that the conditions are still the same as those which were observed by CWC in 2017,” the report said.

The CWC order was stayed by the Orissa High Court in an interim order dated 11 September 2019, till the next week, which was supposed to happen four weeks after the date of the order. There is no information on the Orissa High Court website on further proceedings.

“A tribal student once came up to me with a sunken face and said ‘we are all monkeys, we’ll learn what you teach’,” said a former teacher.

NHRC also highlighted that the CWC had directed the Kordha District Magistrate to make a joint inquiry committee to investigate the issues for proper action in the best interest of children, but such an investigation was never carried out, and KISS never complied with CWC recommendations.

In the cramped spaces of KISS, a student from Nabarangpur said, “he felt like he was in a jail.” Multiple reports by government bodies refer to KISS students as ‘inmates’. But many parents, despite being disgruntled by the state of affairs at the institute, continue to send their child back to school.

The students, alumni, and parents’ association take strong offense to KISS being termed a ‘jail’ and call it a ‘fake narrative’. “Prof. Achyuta Samanta has devoted his entire life to changing the destiny of over 8 lakh tribal families through education and love, without taking a single rupee in return,” they said.

The class XII student hopes to be a lawyer one day. Even though he spoke to his father expressing a desire to drop out of school in 10th grade, financial compulsions meant he had to return to KISS.

“I tolerate the living conditions of my kids because that is the tradeoff for me. That is the only way I can educate them. If he becomes successful, earns good money when he grows up, then this is great. Otherwise, all these struggles were a waste,” his father said.

There’s some relief when students move to junior college. Once the 16-year-old from Koraput moved to class 11, he shifted to a new hostel that is better equipped, with 2-tier bunk beds and only 50 boys to a room. There are also ceiling fans in this hostel.

“There are fewer students in Class XI & XII, but the condition of hostels till Class X is really bad,” he said. The hostel campus for classes XI and XII is different, with fewer students joining in.

KISS students live in a different universe once inside the main gate. They can’t carry mobiles or outside food. And a strict code guides the daily workings. Students are frisked at the gates, and any mobile phones confiscated are broken in front of their eyes, a former staff member, Raja Sundesaran, said.

ThePrint couldn’t access any recent photos of the school hostel, and entry inside was not allowed. Students speak to parents ‘secretly’ with phones smuggled in, and usually don’t get to talk to them more than once or twice a month, if at all it is possible.

The environment is isolating. Students are not even allowed to interact with their siblings, even if they’re on the campus but studying in a different class. With little or no transition or adjustment period, Adivasi children are pushed into a whole new environment with rigid rules and timetables that govern society.

“A tribal student once came up to me with a sunken face and said ‘we are all monkeys, we’ll learn what you teach’,” Madhumita, a former teacher at KIIT’s Institute of Rural Management, where she taught 10 tribal children as well, said.

“The kids have been indoctrinated, and often lose their sense of self-confidence and respect at KISS. It is a humiliating experience to both teach and study there,” she added. She was let go from the institute in 2019, when she was debating on the Kashmir issue on news channels in Odisha.

“My brother studies in the same grade that I do, but he lives in a different hostel. And I am not allowed to speak to him. I don’t know why they don’t let me speak to my brother, it’s just the rule there,” the first student quoted in the story said.

Parents are also not allowed to enter the hostel, and visit their children. A parent, speaking to ThePrint over the phone from Koraput, said that whenever he would visit Bhubaneswar to meet his children, he would be asked to wait for at least 7-8 hours under the sun outside the information office, before he was allowed to see his child briefly.

“When my son was hospitalised at the Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences (KIMS) because of an infection in 2018, I was not allowed to go and visit him. I had travelled 600 km to see him, but I was dismissed from the gate itself,” the parent said.

KISS website mentions that it is an organisation registered under Societies Act 1860. The founder, Achyuta Samanta, in previous interviews, has said that the District Collectors and police personnel ‘recruit’ students from tribal areas for KISS.

But KISS remains the port of call for tribal parents. Since 2014, Odisha has been shutting down schools in areas with low enrolment. More than 7,400 schools have been merged into nearby schools. This makes access to formal education extremely difficult for tribal children. Unable to travel long distances, they enrol in residential schools like KISS.

Podra, a student from Kandhamal who studied at KISS till Class 10, said that he was subjected to corporal punishments on multiple occasions.

“When I was in the 7th grade, I was playing in one of the hostel verandahs, during study hours. A supervisor saw me and grabbed me, and took me to their room. Afterwards, four teachers hit me simultaneously. As I cowered in a corner, they continued to hit me and even kicked me on the back. I fell down, but they didn’t stop,” the boy told ThePrint over the phone. “I have also witnessed a student getting kicked in the gut,” he added.

Another student who is now an official with the Odisha state government recalled the difficulty in using toilets at KISS. He studied at the institute till 2022.

“The washrooms didn’t have doors. 24/7, there was a line in front of them, and they were never cleaned. Urine infections were common even among boys. It might sound funny to you, but if you ever felt strong pressure to use the loo… You just couldn’t, there was always a line,” said the former student who pursued his graduation from KISS.

After studying at KISS, tribal children do get opportunities to grow. A former student is now doing her double master’s in science from a leading IIT.

“I was the gold medallist at KISS. I think I learned a lot from there. Yes, problems were there but I also got access to education,” the student told ThePrint. She said the hostels were cleaned by the students themselves, and the students were also given soap, sanitary napkins, and detergent powder, she said.

Students also complained of tuberculosis and scabies outbreaks on the campus, which they said are commonplace. However, they alleged that tuberculosis-positive children are not segregated.

One of the student interviewees said they had been diagnosed with tuberculosis when they were in the fifth grade, but did not receive adequate medical assistance from the institute.

Female students on campus are also not allowed to venture out, the students said, while the boys above 10th grade get permission to go out of campus on Sundays.

The CWC had noted that, according to KISS staffers, 20 students were suffering from TB, when the committee had visited in 2017.

“Though the management explained that the children’s health check-up is done prior to the admission, and there is a separate hospital for children (KIMS). But in practice, there is no sick room adjoining the hostels to accommodate the sick children,” the CWC report said.

Now, the Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences has a dedicated 100-bed facility on campus for the students.

‘Missing’ children

Behind the barbed wires that protect the walls of KISS, students dream of running away. Some even succeed.

The three students (two of whom are current students of the school) that ThePrint interviewed said that it was common for students to try and escape the school, and many have gone missing.

In 2017, the CWC received a petition from lawyer Subas Mohapatra based in Bhubaneswar, making grave allegations about children missing from the institute.

In his petition before the CWC—a quasi-judicial court—Mohapatra alleged that there was trafficking of children and sexual abuse in the institute. A five-member committee of the CWC then conducted an investigation but did not comment or probe the allegations of trafficking or sexual abuse levelled by the petitioner.

The CWC found that the children do not have enough supervisors or grievance redressal mechanisms. And children often run away from school. A current senior CWC member, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said that since 2023, the committee has received at least five students of KISS who had escaped and were found by the railway police.

“We have found at least 5 cases of children going missing from the campus, and we had called the school authorities too but they never came to pick up the child, that was their callous behaviour. We handed them over to the parents after they arrived,” the member said.

“Every year, my son used to return home during summer vacation. However, since 2015, when he was in Class 9, he has disappeared,” a mother’s police complaint.

The CWC has noticed that no FIR is lodged by the authority in case of missing students.

The case of a missing KISS student, Ram Chandra, who was 16 years old in 2018, even made it to the newspapers.

In April that year, Budai Mandra, the mother of Ram Chandra, lodged a police complaint about her missing child. In the complaint, she alleged that her child had been studying at KISS with help from the Bonda Development Agency. She expressed agony at the fact that neither KISS nor BDA was taking responsibility for her child now that he had gone missing.

“Every year, my son used to return home during summer vacation. However, since 2015, when he was in Class 9, he has disappeared. Other children from the village in the school informed me that he is not in school. After learning this, I collected funds in my village and sent my elder son to look for him. When he inquired there (at KISS), he was told that your brother left for home after appearing for Class 9 exam and has since not returned,” read the police complaint.

However, KISS maintains that the student left the campus with a local guardian after appearing for exams, details of which have been accessed by ThePrint from High Court filings in a habeas corpus petition. The plea was disposed of by the Cuttack High Court.

“There are so many students that even KISS loses count of them, hence many are reported missing. When I was in CWC, we summoned the institute many times to appear before us whenever we found a student of theirs, but shockingly, they never did,” the CWC member said.

Who watches KISS

The Odisha State Commission for Child Rights and the CWC at various points have directed the institute to be registered under the Juvenile Justice Act. But so far, KISS has not complied with this. The former CWC member said that it remains a largely opaque institution where government authorities are unable to conduct regular surveys or investigate the living conditions of children.

The CWC noted that KISS is not registered under the Juvenile Justice Act (2015), even though it houses orphaned children. The institution also does not have recognition from the department of tribal welfare, the CWC had noted in its 2017-18 report, which was stayed in 2019, until the next court hearing.

The NHRC in its report also notes that KISS is in violation of the Juvenile Justice Act (2017).

“It is necessary for the institute to get recognition from the department of tribal welfare, so that the government people can inspect the institution and give proper advice to improve the standard of care. They will be responsible for any deficiency in the standard of care,” the committee had recommended.

Activists often criticise residential schools for tribal children because of the lack of healthcare and poor conditions reported in these schools. According to an RTI filed in 2016, India’s residential schools for Adivasis had reported 882 deaths within a span of five years. Maharashtra had reported 684 deaths, while Odisha had reported 155 deaths in such schools.

ThePrint wrote to the Principal Secretary, Sanjeeb Mishra, inquiring if KISS has been registered with the state’s tribal department. This article will be updated once we receive a response.

Under Section 41 of the Juvenile Justice Act, an organisation, whether private or government, has to register if it provides care to children in need of protection. A Child Care Institute is an organisation that provides care and protection to children in need of such services.

On multiple occasions, KISS has refused to register under the Act. In 2014, the Odisha State Commission for Protection of Child Rights (OSCPCR) had directed KISS to immediately register under the JJ Act (2000), since it is a residential school. In 2017, the court of CWC had again directed KISS to be registered under the JJ Act 2015. In 2019, the CWC again directed the institute to register, but they refused.

The 2014 OSCPCR report noted that tribal girls were concerned that strangers often enter their hostels and take their photos.

“No complaint has been received either by the government or by KISS from any parent/ guardian about the quality of life of any child and CWC has no jurisdiction to inspect KISS with or without notice to KISS. Rather KISS has been praised everywhere for its noble work towards the social cause,” read the institute’s reply in 2019, alleging there is a conspiracy against the institute and blaming the CWC for showing undue favour to activists who are “trying to defame KISS in every possible way”.

The institute claimed that “there is not a single child of KISS hostel in need of Care and Protection” as defined under section 2 (14) of the JJ Act.

However, in various interviews, founder Achutya Samanta has mentioned that education at KISS has helped reduce ‘recruitment’ into the Naxalite movement.

A report by the revenue divisional commissioner, which passed the institute with flying colours in its maintenance of cleanliness, also contradicts some findings of the CWC, like the alleged frequent outbreak of tuberculosis on the campus.

All students interviewed by ThePrint mentioned that teachers and other staff repeatedly reminded them to be ‘grateful’ for KISS and whatever it does for their lives.

The story has been updated to include the voice of KISS students association, KISS Alumni Association and KISS Adivasi Parents Association, who reached out to ThePrint under one umbrella, after the publication of the report.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

What a biased and idiotic article!

If you are so concerned about your child’s safety and consider KISS a threat to his/her well being, please don’t send them to this institution. It’s as simple as that.

KISS officials don’t kidnap children from the tribal communities in Odisha. Tribal families themselves come forward and wish to get their child enrolled.

This is biased reporting. KISS has done a lot for tribal people of Odisha. The unfortunate incidents of KIIT should not be used to blame KISS.

Peddle your agenda….Go on…. what else you guys can do….. shameless