Nagpur/Mumbai: Every day from 7 am, Shashank Gattewar gets a steady stream of pleas from Nagpur residents. “A dog fell from the roof of my house. He’s in pain, how can I help?” asked an 18-year-old girl over the phone. “Anything can be done for iron sewer lines in Mahesh Nagar underpass?” said another resident on WhatsApp. Gattewar dispenses information on everything from tenant verifications and Ganpati Visarjan to-dos to a flyover slicing into someone’s balcony.

The 27-year-old calls himself “Nagpur’s sole corporator” but he has no formal position. He’s a civic issues Instagram influencer. Now for many in the city, he has become what the city no longer has: an accessible, responsive local representative.

“Whenever someone raises a complaint, I forward it to the concerned official in the NMC and follow up with them. Most people are not aware how to reach concerned officials. I have sort of become the liaison between the citizens and NMC,” said Gattewar.

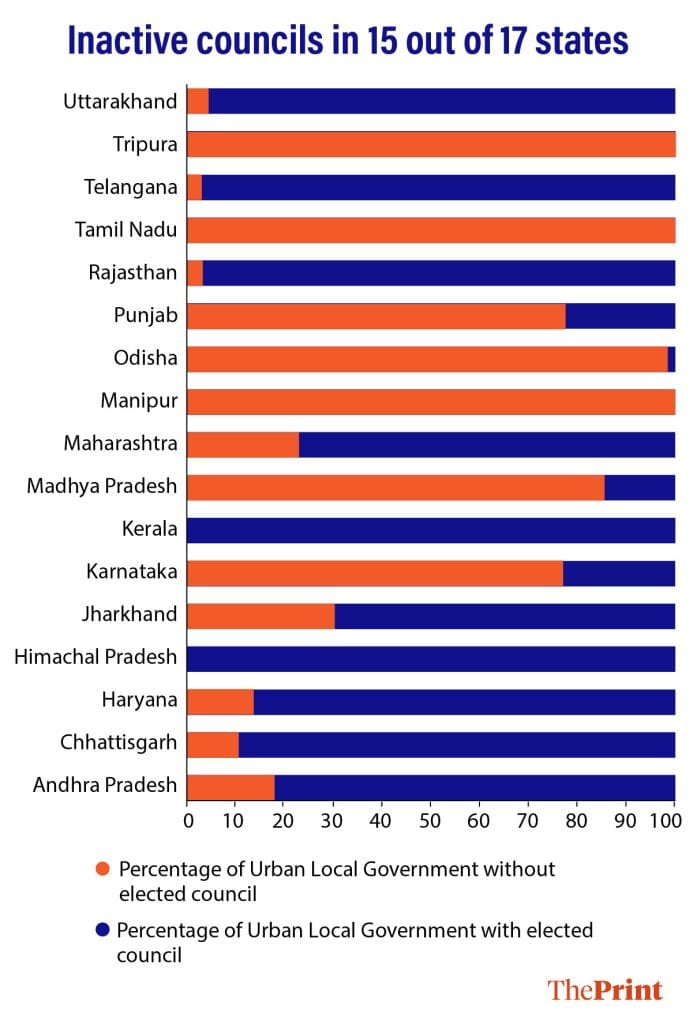

Nagpur hasn’t had elected corporators for three years. Bengaluru has gone without them for five, while Mumbai and Pune have waited more than three. Chennai and Guwahati, too, were run without elected councils for nine years until 2022. Across the country, 1,600 out of 2,625 Urban Local Self-Governments in 18 states do not have elected councils, according to a 2024 report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. That’s about 61 per cent. The average delay in polls is nearly two years.

In Maharashtra alone, elections to 29 municipal corporations, including the country’s richest civic body, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), have been on hold since 2022. The Supreme Court has issued repeated stern warnings, and earlier this month set a final deadline of 31 January 2026 for all local body elections to be conducted in the state.

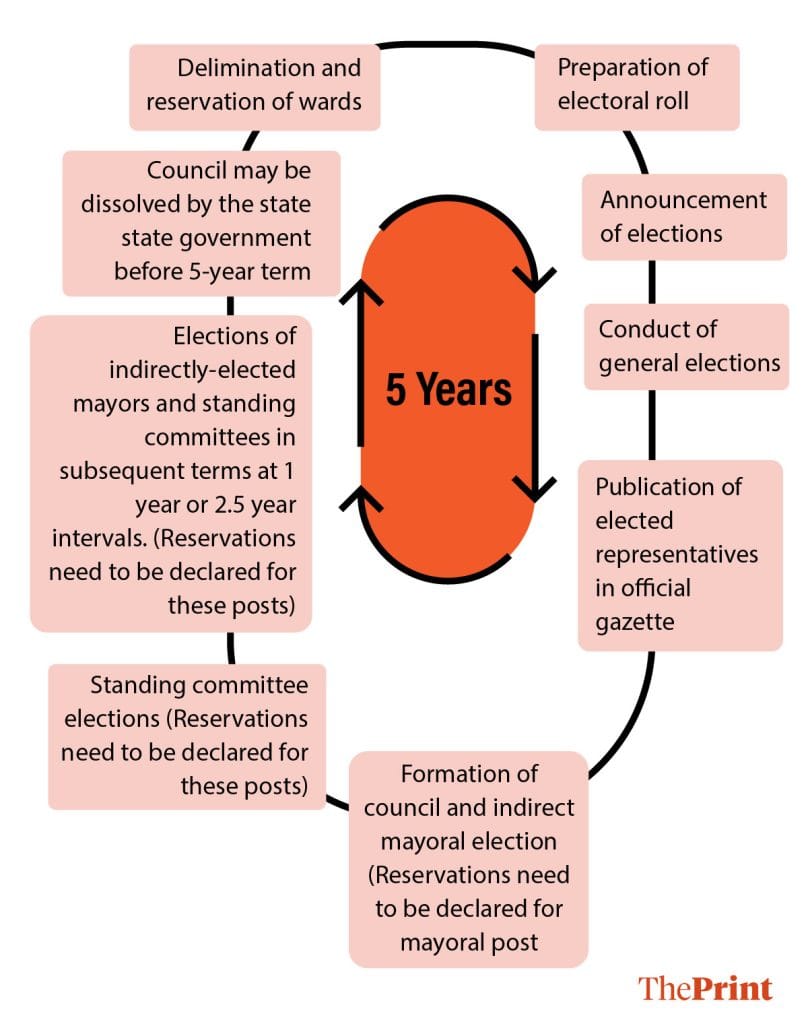

Urban local bodies are grassroots democracies and have a constitutional mandate to be elected before the term of the earlier council expires.

“No country in the world has achieved planned and sustainable urbanisation without robust urban local governance. The key to this robust self-governance is timely elections,” said Srikanth Viswanathan, chief executive officer of Janaagraha, a non-profit that focuses on urban governance. “We discuss the metro, Har Ghar Jal, electric cars… but none of those are as fundamental as timely elections.”

In the last 10 years, he added, India has been going one step forward in urban infrastructure investments but two steps backward in governance reform.

The result is a giant mess in many of India’s metros and flagship Smart Cities. From water supply to waste management to cleaning sewers, municipal governments are meant to handle the frontline of civic infrastructure. Yet more than half are hollowed out.

In some cities, the vacuum is being filled by solo crusaders — the earnest, the ambitious, and the opportunistic. Aspiring youth leaders, former corporators desperate to keep their vote banks warm, and social media influencers have all jumped into the fray to help address grievances and keep the public informed. But there’s only so much they can do.

At a slum in north Nagpur, women are forced to defecate in the open at the nearby railway track. In post-Swachh Bharat India, their toilets are overflowing, the drains and sewers completely choked. But they have no corporator or councillor to raise a complaint to.

“It’s not that the nagarsevak (corporator) was very helpful. But at least we had someone to go to and get our work done,” said resident Chanda Devi.

With NMC elections expected after Diwali, former corporators from all parties are reportedly lobbying for funds and clearances for roads, retaining walls and nullah repairs. Ex-corporator Gopi Kumre is reportedly pushing projects worth Rs 3 crore. But such last-minute activism is being met with a healthy dose of scepticism,

“Nagpur has been orphaned without corporators. A corporator is a ‘mini-MLA’ working on health, sanitation, and civic issues. They were accessible even in the middle of the night. Without them, people, especially the poor, have nowhere to go,” said Yash Gourkhede, founder of Nagpur’s Jan Badlaav, a political platform that plans to field candidates in the civic elections.

Also Read: Brand Bengaluru is stuck on bad roads. MNCs, startups are saying ‘Hello Hyderabad’ now

‘Quasi corporators’

A parallel system of municipal governance has grown in Nagpur, from Instagram fixers and meet-up groups to “quasi corporators” with political backing.

On the face of it, the city— the headquarters of the RSS, the hometown of Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis— looks spic and span with wide roads, green neighbourhoods, and big infrastructure projects. But when there’s a problem like waterlogging or a clogged sewer line, there’s confusion about who to turn to.

The reason Nagpur — and much of Maharashtra — has no elected corporators lies in a legal tussle. In 2021, The Supreme Court struck down a Maharashtra ordinance that had introduced 27 per cent OBC reservation in local bodies, saying such a quota could be given only after fresh empirical data proved the numbers.

Meanwhile, scheduled elections were suspended. For years, petitions and counter-petitions kept the issue tied up in court. Deadlines were given and then crossed. It was only in August 2025 that the Supreme Court dismissed the challenges and upheld 27 per cent OBC reservation, paving the way for elections in 29 municipal corporations, 290 municipal councils, 32 district councils, and 335 panchayat samitis. The State Election Commission has been ordered to complete delimitation by 31 October and conduct polls in January.

Until then, municipal governance in many places has become a matter of jugaad.

Every Sunday at 8 am, Shashank Gattewar would organise park meet-ups to hear civic grievances, though he now relies mainly on online platforms. He has also made multiple WhatsApp groups for residents to raise complaints, including one dedicated to “dog parents”.

We were inundated by requests from people for corporator-level tasks. So much so that we made a ‘parallel body’ to help people. We have appointed 24 workers in all the wards of West Nagpur, who are working as quasi corporators

-Ketan Thakre, general secretary of Maharashtra Pradesh Congress Committee

On Instagram, he describes himself as “NOT a Journalist, Politician/Activist. Just an Active Youth Citizen”. His current following of 23,000 was built in less than two weeks, as Meta deleted his earlier page. Gattewar, who claims no explanation was given, is contesting the deletion. The new page is a mix of activism, self-promotion, and occasional ads for local businesses.

Residents credit him with quick solutions to their problems. “We rescued a dog successfully. Happiness! @ShashankGattewar thank you for your help,” said one Instagram commenter. “I once asked him for help when water logging was there in our society… and within 3 hours, the road was cleared,” said another on a Reddit post. He often tweets about local issues, tagging central agencies like the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI).

NHAI on Ashok Chowk lafda

•During construction, NHAI identified encroachment & requested NMC for removal action. (but no action)

•House built without any sanctioned building plan.

•Property owner extended balcony beyond plot boundary

Now, the portion will be demolished. pic.twitter.com/HaqZUyLXST

— Shashank Gattewar | Nagpur (@SGattewar_NGP) September 14, 2025

Gattewar learnt the ropes and red tape of the Nagpur Municipal Corporation by handling its social media accounts four years ago. He rose to prominence during the Covid-19 lockdowns.

“In 2020 and 2021, I was helping people procure oxygen cylinders and secure hospital beds in Nagpur, that is when I became popular in the city. After Covid people still contacted me for any assistance that they needed,” he said. Ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, he was among a small group of influencers contacted by BJP’s Devendra Fadnavis to help with campaigning.

Driving around the city, he keeps tabs on civic problems from potholes at busy intersections to new waste-dumping sites, with complaint letters at the ready.

While he harbours political ambitions and wants to be a ward corporator, he is waiting it out.

“The problem is, there isn’t one single ward that I am operating out of. The entire city knows me, but I don’t have a strong voter base,” he said.

But he is not the only self-appointed ‘corporator’ on the ground. Political parties also have stopgap civic leaders.

Nagpur West MLA and Congress city president Vikas Thakre has hired a team in 24 wards of his constituency to help people with their day-to-day civic issues.

“We were inundated by requests from people for corporator-level tasks. So much so that we made a ‘parallel body’ to help people. We have appointed 24 workers in all the wards of Nagpur West, who are working as quasi corporators,” said the MLA’s son Ketan Thakre, general secretary of Maharashtra Pradesh Congress Committee.

These ‘quasi corporators’ now step in for everything from securing birth or death certificates at the corporation office to following up on complaints about stray dogs. One, perched on his Splendor bike, was on his way to the NMC to help a neighbour get admitted to hospital.

In Mumbai, meanwhile, a citizens’ forum and ex-corporators are acting as checks and balances on the BMC.

Mumbai’s citizen watchdogs

For the last 11 years, advocate Trivankumar Karnani has been acting as the conscience of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation. In 2014, he founded the Mumbai North Central District Forum (MNCDF), which now has 150 members spread across the Mumbai Metropolitan region.

“We work on civic accountability, citizen welfare, and matters concerning the larger public interest. Through this forum, I use knowledge of law to give back to society for its upliftment,” said Karnani.

On social media, Karnani and other MNCDF members post visuals of meetings with BMC officials, police, or IAS officers. MLAs tag them when they want to flag issues to the municipal corporation. The captions accompanying their photos and videos of civic problems are drafted almost like complaint letters to the BMC — about uncollected garbage, ‘illegal midnight digging,’ or traffic jams at Dahisar toll plaza due to bad roads and slow-paced metro work.

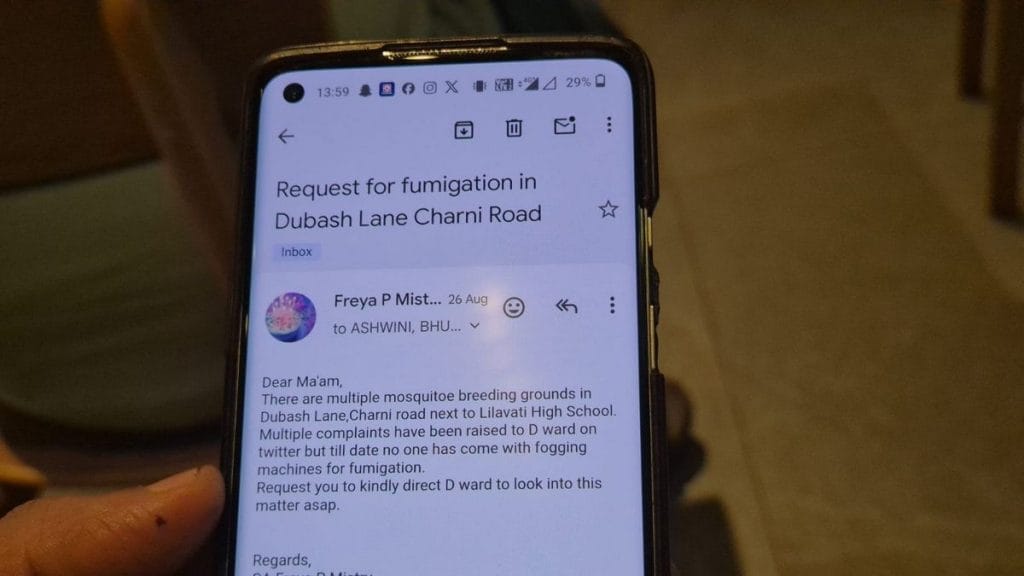

Karnani’s inbox is overflowing with civic complaints. ‘Request for fumigation in Dubash lane, Charni road,’ read one subject line. Others warned of ‘ILLEGAL ENCROACHMENT AND UNAUTHORISED BANNER’ and ‘School children at risk—rising number of stray dogs at Delta Tower one’.

If work is not done on time, we remind officials that they need to finish, or they will be penalised for dereliction of duty. We use knowledge of law to have these issues resolved with the competent authorities

-Trivankumar Karnani, founder of MNCDF

“We have seen a 100 per cent increase in the number of complaints filed to us in the absence of corporators,” Karnani told ThePrint at a cafe near the trial court. “Without corporators, there is a lack of communication channels between the BMC and citizens. This is where our role becomes even more proactive. We are the only bridge between citizens and the authorities.”

The MNCDF has a “flying squad” of 150 people — journalists, doctors, lawyers, homemakers — spread across wards, according to him. Ward leaders stay closely connected to resident welfare groups and raise issues directly with the corporation.

“If work is not done on time, we remind the officials that they need to finish, or they will be penalised for dereliction of duty. We use knowledge of law to have these issues resolved with the competent authorities,” he added.

In his view, the absence of corporators has stripped away a vital democratic check. Governance has become more difficult with the administration free to execute decisions without public representatives to keep it in check.

Over the years, MNCDF has tried to perform that role by pushing officials to take up issues within a stipulated period and by scrutinising projects that would normally have gone before the standing committee, the powerful BMC body that oversees the day-to-day business of governance as well as financial accounts.

Karnani pointed to the BMC’s controversial Rs 800 crore ‘beautification’ drive and its Rs 12,000 crore road concretisation project, saying the planning was unsystematic. ThePrint had earlier reported how the concretisation turned Mumbai into a ‘maze of rubble’.

One of the citizen group’s biggest battles with BMC was over the proposed Rs 2,400 crore bridge to connect Khar West and East, which was already linked by a railway underpass. Residents argued it was wasteful and would worsen traffic and congestion.

“It was an absurd plan and tender,” scoffed Karnani. MNCDF and local residents’ associations lobbied senior BMC officials and Bandra West MLA Ashish Shelar to scrap the project, with the matter even reaching the CM. They threatened to move Bombay High Court and also pointed out that BMC itself had rejected it in 2018. The plan was shelved last year.

Ideally, such objections should have been aired in the standing committee, Karnani said. In its absence, citizens are forced to be more vigilant and take up cudgels in lieu of corporators.

Ex-corporators, grassroot leaders in the fray

At ward 102 in Bandra West, former corporator Rahebar ‘Raja’ Khan sits in a decrepit, damp-walled office thick with cigarette smoke, files threatening to topple from overstuffed shelves. Outside, residents wait their turn on plastic chairs to get five minutes with their ‘nagarsevak’,

Khan is one of several ex-corporators who still hold sway in their wards. Some have even hired their own teams to clean drains and collect waste. His phone buzzes constantly with requests for fumigation, birth certificates, hospital admissions. He manages it all with a motley crew of five workers who, on a stormy September afternoon, were clearing rubble from a demolished structure in the ward.

“If we go to the corporation, they don’t entertain us. Without Raja bhai we won’t be able to get any work done,” one resident waiting outside said.

For Khan, whose wife Mumtaz has also been a corporator here—both as independents—there’s no option but to work for the people here. If he withdraws, he risks losing clout and goodwill, and the ward itself would suffer.

“In the set-up of representatives, MLA or MP, the most important is a corporator, because they are most connected to the ground, see the area, and meet the people,” Khan said. “Once I was elected, people had certain expectations of me, they had faith that I would deliver.”

But there’s a distinct class divide in how the absence of corporators is experienced by residents. In gated communities, it barely makes a difference. But for the less privileged, who once depended on their nagarsevak for every clearance and complaint, it stings like a bee.

These are not secondary elections, but are to be accorded the same heft [as Assembly or Lok Sabha polls]

-JS Saharia, former Maharashtra election commissioner

In Nagpur’s Cotton Market, the weekly Shanichar bazaar — described by a local shopkeeper as “DMart for the poor” — has been ripped apart. Riots in the nearby Taj Bagh area earlier this year led to a clampdown on street vendors. Now their wooden carts lie outside the municipal office with wheels chopped off. Entreaties from vendors, Hindu or Muslim, have fallen on deaf ears. Many are convinced that this wouldn’t be the case if they had a corporator to advocate for them.

“Earlier, when police came and seized our stuff, we could go to the nagarsevak and get our stuff back. Nagarsevaks would actually give good representation. Now there’s nobody to listen to us,” said Imran, a shoe vendor.

One prominent voice taking up their cause is Yash Gourkhede of the Jan Badlaav movement, who contested the assembly election last year under the Vanchit Bahujan Aaghadi banner. On 20 September, he led a massive rally in support of vendors. He also alleged a “thela scam” — NMC officials seizing handcarts and selling them as scrap.

“Even the vendors with licenses are not allowed to be here. The municipal corporation is killing all sources of livelihood for poor vendors. NMC cannot provide employment, but it shouldn’t take it away either,” Gourkhede said.

Under his Instagram handle ‘Nagpur ka beta’, which has 17,000 followers, he often takes on the NMC, whether it’s describing a waterlogged road as “Nagpur smart city swimming pool” or the so-called “thela scam”. Gourkhede plans to contest the upcoming civic elections, with Jan Badlaav fielding candidates in all wards.

‘Disinclination to share power’

Nowhere is the breakdown of municipal governance more visible than in Bengaluru, where pothole-riddled roads have become an embarrassment. Soon after the CEO of BlackBuck warned his company might move out of their office over the state of Outer Ring Road, the chief minister set a one-month deadline to fix potholes.

Even the chief secretary was later photographed on the streets, directing engineers himself. Many blame the situation on the city’s lack of municipal elections, now overdue for five years.

“As the highest state officials are now reduced to supervising Bengaluru’s potholes, it tells us everything about the collapse of urban governance,” BJP MP Tejasvi Surya wrote on X. “Unless we make municipal institutions as important as Parliament and the Assembly, empower them with authority and accountability, and ensure regular elections, our cities will never grow into the engines of development they are meant to be.”

There cannot be a bigger advertisement for the state of our urban (mis) governance – than this photograph.

The Chief Secretary of Karnataka, the top bureaucrat of the state, is personally inspecting roads and instructing local officials to fill potholes.

The Deputy Chief… https://t.co/UCW3OmQqMA

— Tejasvi Surya (@Tejasvi_Surya) September 23, 2025

Such delays in civic elections are often rooted in politics, according to a 2025 report by Bengaluru-based advocacy group Janaagraha.

“It is widely felt that elections to local governments and council formation face delays due to political considerations,” the report reads.

It notes that state governments frequently stall polls by announcing municipal reorganisations, initiating ward delimitation, or withholding and revising reservations — as seen in Maharashtra. Such moves, the report says, are often timed just before elections and used as pretexts to indefinitely defer council formation and standing committee elections.

“Disinclination among legislators, ministers, and bureaucracy to share power with councillors/mayors results in using ward delimitation and reservation as a pretext to delay elections,” the report added.

Srikanth Viswanathan of Janaagraha said there’ve been serious lapses in conducting civic body elections.

“We have reached a stage in India where it is unthinkable for state elections to be delayed. In the 80s, ad hoc dismissal of states used to happen… we have moved on from that situation. And now up to 1,700 local governments don’t have elected councils. The average delay is about 22 months,” he said.

The report has recommended a standardised framework for local elections, modelled on the Representation of the People Acts, 1950 and 1951. Civil society and citizens, it urged, must come together to demand timely urban local body elections and make this a “politically salient” agenda.

Municipalities in India have constitutional status under the 74th Amendment of 1993, also called the Nagarpalika Act, which obliged states to adopt them as democratic units of self-government. The amendment warned that in many states, local bodies have become “weak and ineffective”, on account of “failure to hold regular elections, prolonged supersession and inadequate devolution of powers and functions.” As a result, they are unable to perform effectively as the “vibrant democratic units of self-government” that they are supposed to be.

Former election commissioner of Maharashtra JS Saharia, has reinvented himself as a civic poll crusader. As chairman of the governance-focused non-profit ISHAD, he has been filing RTIs, moving courts, and running workshops to spotlight the crisis

“We found out that elections are simply not taking place in multiple states, so we started collecting data through RTIs filed across the country. We learnt that nearly 50 per cent of civic bodies have not had elections in India, which is a very serious matter,” he said. “We approached the Supreme Court for pan-India, pleading that six months before elections are due, no new law should be effected.”

Saharia added that there is a ‘glitch’ in the Constitution that allows state legislatures to frame any law, which the state election commission is bound to follow. To generate awareness, ISHAD has been conducting workshops in schools about the importance of municipal, state, and parliamentary elections, especially targeting Class 11 and 12 students who will soon be first-time voters.

Based in Navi Mumbai, the organisation doesn’t even have a permanent office, working instead out of libraries and the premises of other grassroots organisations.

“Even the bureaucracy and political leadership or civil society are not aware of the 74th and 73rd [Panchayati Raj] amendments,” Saharia said as rain battered outside. He added that ISHAD is engaging with universities to make local body elections part of daily campus conversation, with councillors or officials brought in to explain why they matter. “We need it to happen on a daily basis.”

ISHAD has held sessions with police, government officials, and political parties as well, stressing that civic elections are as important as state polls.

“These are not secondary elections, but are to be accorded the same heft. I had to take at least 10 meetings [across Maharashtra cities] to ensure that the collector takes equal interest in local body elections, and so does the media,” Saharia added.

Also Read: Built to fix cities, billionaire-funded, 16-yr vanvas—story of Bengaluru’s IIHS University

Disconnected governance

In Maharashtra, the civic body election logjam has turned highly political. State control of city budgets has further centralised urban governance. Former corporators complain of being locked out of offices in the BMC. Opposition corporators allege funds are unevenly released.

In November last year, for instance, the BMC released Rs 500 crore for civic work to corporators, which reportedly went only to BJP-Sena (Shinde faction) corporators. Earlier this year, former Kalyan-Dombivli Municipal Corporation (KDMC) corporator Vikas Mhatre and his wife, Kavita, resigned from the BJP, alleging less development funds compared to MNS and Shiv Sena counterparts.

On the ground, there’s a glaring disconnect between what residents and the municipal corporation prioritise. Mega-projects like the proposed Khar bridge or road concretisation take precedence over daily disasters such as flooded roads and uncollected garbage.

“Work happens through the state. There’s a huge divide between what is designed and what’s happening on the ground,” said Sunny Chheda, a Bandra West resident.

Looking at Mumbai’s dug-up roads, expensive beautification projects, and lack of representation, many residents echo the same sentiment: they long for the pre-2022 BMC, when someone was at least accountable.

“Who do we ask these questions to? As a citizen, I feel completely disempowered,” said Chheda.

This article is part of Urban Pressure, a series on how bad planning is choking Indian cities.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)