Tehri Garhwal: Dhaba cook Kuldeep Kathait knocked desperately on the medical superintendent’s door. He wanted help for his 22-year-old wife Raveena, who lay writhing in pain on a wobbly steel bed a day after giving birth at the primary health centre in Pilkhi village of Ghansali sub-district. The superintendent shooed him away without even opening the door, Kathait alleged.

“He said the doctor will come in the morning and see her. He said he couldn’t do anything, so I shouldn’t waste time and should give her confidence to bear the pain,” Kuldeep recalled, his eyes brimming with tears. That night, 24 October, Raveena died. It was their third wedding anniversary.

This time, instead of mourning and resignation, there was anger. Raveena’s death came barely a month after another young woman from the same village died under similar circumstances. The two preventable deaths so close together became a breaking point. It’s hills vs plains again, centred now on healthcare. The rage over unequal access in the hill districts has boiled over into an agitation stretching from Almora to Tehri Garhwal. In Almora, they’re calling it Operation Swasthya and in Chamba it’s Jan Sangharsh, but the demands remain the same: more doctors, functional hospitals.

Even as the agitation picked up pace, at least two more people in Tehri Garhwal died due to the alleged lack of health facilities — 48-year-old Pooran Singh in October and 23-year-old Neetu Panwar on 18 November.

“Hum hamara haq maangte, nahi kisi se beekh maangte” (We demand our rights, we don’t beg from anyone), reverberates through Tehri Garhwal, where several villages have been holding indefinite agitations. On 24 October, protesters started a 300 km march from Chaukhutia in Almora to the Uttarakhand Assembly in Dehradun until police stopped them. In Ghansali, Kathait goes daily to the PHC where hundreds have been protesting against what he calls the “broken medical infrastructure” that took his wife’s life.

From mashal marches to letters written in blood to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, residents say the state must solve the collapse of healthcare in the hills.

A week after Uttarakhand celebrated its 25th anniversary as a state on 9 November, with PM Modi praising its “development journey” and unveiling Rs 8,000 crore in projects, the protests only grew louder. Villagers from Nainital’s Garampani to Thauldhar in Tehri Garhwal sat on days-long dharnas. On Monday, talks collapsed between protesters in Almora’s Bhikiyasain and the health administration. In Chaukhutia, residents kept shouting “Swasthya sewayen bahal karo, doctor do, aspatal bachao” — improve health services, give us doctors, save hospitals — even as the state celebrated its silver jubilee.

Why was Uttarakhand formed? We felt neglected. We believed a separate state would bring better development to this hilly region. But what we are witnessing today is that our situation has only worsened

-Sunita Rawat, district chairperson of the Uttarakhand Kranti Dal’s women’s wing.

The scale of the crisis is evident in a 2024 CAG report on the public health infrastructure in Uttarakhand. Covering the period from 2016 till 2022, it noted that while there’s a policy in place for recruiting general duty medical officers, there’s none for specialist doctors, leading to shortage of 94 per cent in community health centres, 45 per cent in sub-district hospitals, and 30 per cent in district hospitals. The hills-plains divide is stark. Specialist posts in hill districts have a 70 per cent vacancy, compared to 50 per cent in the plains. It’s a similar story with nurses and medical technicians.

Uttarakhand was created in 2000 on the promise that Garhwal and Kumaon would finally get the development and political representation they lacked. Today, those very regions are agitating again for something far more basic: the right to healthcare.

The Uttarakhand Kranti Dal, which once spearheaded the statehood movement, has come out in support of the protests. Even the State Legal Services Authority (SLSA) has sounded an alarm. During a public interest litigation hearing at the Uttarakhand High Court last week, it highlighted the “acute shortage of basic facilities in the state’s hilly base and district hospitals,” saying that most were operating only as referral centres. It pointed out that not only were people there vulnerable to disasters like landslides and cloudbursts, they could not even get basic care.

“Today, the government is celebrating 25 years of Uttarakhand. But this is exactly when we should revisit a basic question. Why was Uttarakhand formed? We felt neglected. We believed a separate state would bring better development to this hilly region. But what we are witnessing today is that our situation has only worsened,” said Sunita Rawat, district chairperson of the Uttarakhand Kranti Dal’s women’s wing.

Also Read: Dementia wave is hitting Indian homes. Families are exhausted, healthcare unprepared

The death that started it all

The flashpoint that brought the hill districts of Uttarakhand together in grief, anger, and protest was the death of 21-year-old Pilkhi resident Anisha Rawat.

The low-ceiling room that she shared with her husband Jaspal Singh is plastered with photos of her — smiling, dancing, holding his hands. Even the clock on the wall carries her face as its background. They were meant to celebrate their first anniversary in a month.

Memories of her last days haunt him.

“She was in immense pain. She kept saying her legs hurt,” he said.

In Pilkhi, located over 200 kilometres from Rishikesh, a pregnancy is met with dread, not celebration. The lone primary health centre is 20 kilometres away in the Ghansali market, with barely any doctors. There are no proper roads, and reaching it takes at least two hours by foot over uneven, rocky terrain that snakes through the vale.

During her pregnancy, Anisha would trek to the market whenever she needed a break from household work — just as her mother-in-law Uttam Devi had three decades ago. Little has changed here. Natural childbirth is seen as the only option. Even if there’s an emergency, the PHC has no doctors to perform a cesarean.

A week before her scheduled delivery in September, Anisha went to stay with her sister-in-law, who lived near the hospital on a pucca, motorable road. After hours of labour in the PHC’s rudimentary ICU, with peeling walls and a creaking bed, she gave birth to a baby boy. And then she started haemorrhaging, allegedly from a perineal cut made carelessly to facilitate the delivery.

There are no specialists. There is no equipment. That’s a call our higher-ups have to take. Residents are protesting, and we’ve raised these concerns in meetings, but we can’t go beyond that

-government doctor in Pilkhi

“Instead of keeping her under observation, they asked us to take her home within 12 hours. I kept saying she was bleeding, but the medical staff refused to listen and said it was routine,” said Sarveshi Devi, her sister-in-law.

That evening at Devi’s home, Anisha began complaining of breathlessness. Jaspal rushed her to the PHC, from where she was referred to Rishikesh.

“I had no trust in the government doctors, so I took her to a private hospital in Rishikesh,” he said.

But she didn’t make it. Doctors said she had lost too much blood. Anisha could not even hold her newborn son once.

Uttarakhand’s maternal mortality rate stands at 103 deaths per 100,000 births, higher than the national average of 97, and its infant mortality rate is 39.1 deaths per 1,000 births compared to 35.2 nationwide, according to the 2024 CAG report.

A doctor at the PHC in Pilkhi said they often refer patients elsewhere because they “can’t take risks”. The staff isn’t well trained and a few can’t even do the basics.

“There are no specialists. There is no equipment. That’s a call our higher-ups have to take. Residents are protesting, and we’ve raised these concerns in meetings, but we can’t go beyond that,” he added.

‘What is this development for?’

The anger had been simmering even before Anisha Rawat’s death. In July, Shubhanshu Joshi, a one-year-old child from Chamoli’s Gwaldam died after he was shunted between four hospitals following his initial visit to the PHC for severe dehydration. There was no paediatrician at the PHC and no paediatric ICU unit at the district hospital.

“It appears that negligence has been shown by officials and employees in the discharge of their duties. Immediate investigation orders have been given to the Kumaon Commissioner,” Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami had posted on X.

The Joshi family’s ordeal struck a chord and protests began soon after. But they gathered real force after Anisha’s death in mid-September. A day after her death, shopkeepers, social workers, and villagers shut down the Ghansali market and marched to the Pilkhi primary health centre, raising slogans against the Health Department, the district administration, and local MLA Shakti Lal Shah. District panchayat members joined them and called for an inquiry.

WhatsApp groups were flooded with calls for justice for the hill districts of Uttarakhand. MLAs and panchayats came out in support of the protestors.

As the Ghansali Swasthya Jan Sangharsh Morcha took shape in Tehri Garhwal, Operation Swasthya was launched in Almora’s Chaukhutia in October. As the protest march from Chaukhutia reached, Dehradun, the matter even reached the state assembly.

“A protest has been going on in Chaukhutia for 35 days over poor health facilities, but the government has not taken cognisance,” said Leader of opposition Yashpal Arya. “This is a people’s movement. The norms of the CHC are not being fulfilled.” BJP state minister Subodh Uniyal responded measures had been taken.

On 16 October, the Uttarakhand government launched mobile medical unit vans to bridge gaps in healthcare access. Chief Minister Dhami also announced plans to add an X-ray machine and another 20 beds to the 30-bed Chaukhutia PHC.

“The government’s effort is that the people in the hills should not have to rely on big cities for better medical facilities,” he said.

Meanwhile, in October, Raveena died in Pilkhi and 48-year-old Pooran Singh lost his life after allegedly being refused treatment at CHC Balesur following an accident. On 18 November, another pregnant woman, 23-year-old Neetu Panwar from Shrikote in Chamoli, died on the way to hospital after being referred from CHC Balesur — the same centre that turned away Pooran Singh. Her death triggered fresh outrage over the constant referrals caused by the shortage of specialists.

There’s a wave of social media posts demanding accountability for her death, shared alongside a photo of her lying in the back of a car.

“It’s been 25 years since Uttarakhand was formed… and there are still no proper facilities for pregnant sisters! Then what is this ‘development’ for?” read one Facebook post. Another said: “Khaak vikas hua pahadon ka [Development is zilch in the hills]. People are still dying today due to lack of treatment.”

Whatever is happening in Uttarakhand is wrong. My people are suffering. I am apprising the government on their behalf

-former Tehri MLA Dhan Singh Negi

Amid calls for his resignation, Tehri Chief Medical Officer Dr Shyam Vijay released a video saying Neetu Panwar had “jhatke” (seizures) at home and that her blood pressure was found to be extremely high at the health centre and so she was referred out. He attributed her death to pre-eclampsia, a serious pregnancy complication. “We will immediately form a team to investigate this case,” he said.

In Ghansali, where a sit-in has been underway for 25 days, protestors have now announced a march for 19 November. “This is a justice journey of sisters of Ghansali. If the DM of Tehri is not able to come, then the people of Ghansali should wake her up,” posted local activist Sandeep Arya. On 8 November, he and others sent a letter written in blood to the Prime Minister through the ADM.

Former Tehri MLA Dhan Singh Negi has also come out in support. At the protest in Chamba, Negi, who is from the BJP, told ThePrint he has been holding meetings with Health Minister Dhan Singh Rawat to brief him on the ground situation.

“Whatever is happening in Uttarakhand is wrong. My people are suffering. I am apprising the government on their behalf,” Negi added.

A dream destroyed

Pooran Singh was buying vegetables when an iron rod from an under-construction building struck his head. The vegetables slipped from his hands as he collapsed on the road, blood streaming down his face. Neighbours rushed him to the community health centre, but the medical staff refused to treat him, saying they weren’t trained. He was referred instead to a hospital in Rishikesh. Singh never made it that far.

“The medical staff at the community centre didn’t even bandage my father or take any preliminary steps to stop the bleeding,” said 27-year-old Manish Singh, Pooran’s son.

The costs of these preventable deaths are also financial. Manish, who had been saving money by cooking at dhabas and hoped to become a chef, now has to care for his mother and younger brother. Instead of honing his skills, he takes up whatever short-term work he can, just as his father did, to keep the family going. It still isn’t enough.

“I wanted to earn and build a house in Rishikesh. All my life, I have seen my parents struggling for basics. And the government has only given us assurances,” he said, wiping his tears. “I want the government to compensate our families for the loss of our loved ones. Who will run our house now?”

Also Read: A cough syrup’s trail of death, Kanchipuram to Chhindwara. ‘Son’s life cost Rs 30’

Returning for love and war

A makeshift tent at the entrance of the PHC in Ghansali now holds photos of Anisha Rawat, Raveena Kathait, and Pooran Singh, placed on a wobbly table and adorned with garlands. Every morning, 40-year-old Sunita Rawat bows to them before sitting on the dharna.

“They are our martyrs. I derive my strength from them,” she said, adjusting the collar of her black Nehru jacket.

Sunita was a teacher in Delhi-NCR before she returned to her hometown. She wanted to make a difference after seeing how people here were left to fend for themselves during COVID.

“I saw that the people of Uttarakhand are suffering, especially the hilly regions. I felt we are still in 1947 and development is far away. My people are struggling for basic facilities of sadak, bijli, paani,” she said.

How long will women suffer because of the negligence of the politicians and the authorities? It always falls on us

-Matoo Devi, Anisha’s mother-in-law

The dormant rebel in her awoke. She joined the Kranti Dal, the organisation that once led the statehood movement. Now, she and other members travel across Uttarakhand to make people aware of their rights.

“Right to medical care. One should never have to struggle so much for it,” she said.

Sunita’s audience is mainly a handful of elderly men and women; many of the younger men work outside the village.

“Before elections, political parties make big promises. Once you vote for them, they disappear. We must hold them accountable. Ask them about their absence the next time they come to you,” Rawat said, her voice seething with anger. “Join Kranti Dal and together we will change the face of Uttarakhand just like we did in the late 1990s.”

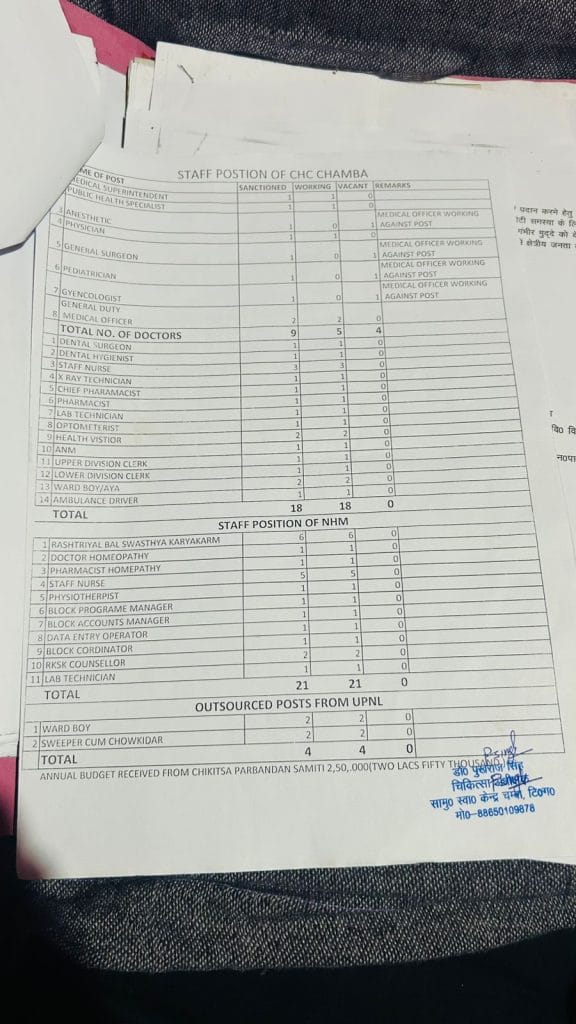

Over 100 kilometres away in Chamba, activist Ankit Sajwan counts the same failures at another protest gathering. Scarcity of doctors. No ultrasound machines. No specialists.

“Every time a doctor comes, within a week they leave. The authorities say no one wants to work here, but why? Because they aren’t given the facilities they need,” Sajwan said.

But sitting near the doorway of her room in Pilkhi, Anisha’s mother-in-law Matoo Devi weeps.

“How long will women suffer because of the negligence of the politicians and the authorities? It always falls on us,” she muttered.

Nearby, Jaspal gently sways his newborn son in his arms. Anisha’s mangalsutra lies on the bed beside them. He scrolls through Instagram videos of Anisha dancing to Uttarakhandi songs.

“This is your mother. She gave birth to you,” he said to his son.

Jaspal said he decided to stay in the village and take up farming to make Anisha happy. Before they married, he worked as a cook in Bengaluru and they were in a long-distance relationship for some time. He wanted Anisha to move there with him. He would show her the tall buildings, the wide roads, the nightlife on video calls.

“It fascinated her. But she never wanted to leave pahad,” he said. “I wish she had listened to me.”

She wanted a simple life, he added. She had simple dreams too.

“She always wanted to drive a scooty. For her it meant freedom, to drive on roads on her own,” Jaspal said. “I always told her she would, whenever there would be a road.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)