Coimbatore/Tiruppur: In stretches of Tiruppur district packed with textile industries, factory owners are murmuring about American buyers asking them to hold orders since President Donald Trump first imposed a tariff hike of 25 per cent. The once-predictable hum of knitting machines now comes in uneven bursts.

R Sathish Kumar, who runs a medium-scale garment unit in Velampalayam and exports T-shirts to American retailers, said that his plan for September has been put on hold.

“Since the American buyers are also unsure when this crisis will resolve, they said that they are looking at Vietnam and other places for textile garments. They want us to reduce the price, but it is impossible for us to reduce the price by 25 per cent when our margins are already very less,” Kumar told ThePrint.

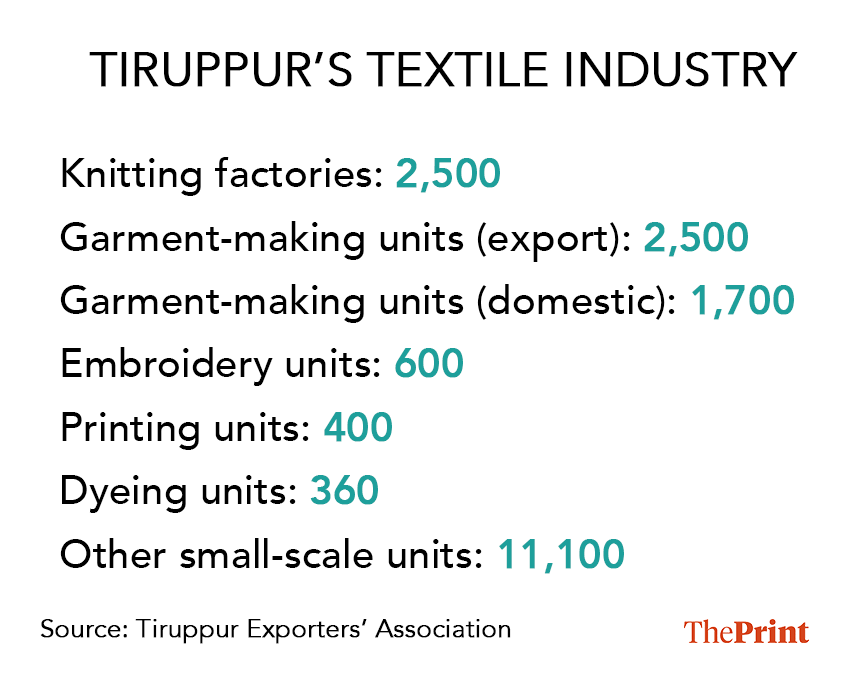

Once a bustling textile hub, where a garment moved smoothly from knitting to dyeing to stitching and packing, Tiruppur is now facing one of the biggest challenges in its history. Even as production continues for now, there is an unease in the air.

“We had two consignments worth Rs 7 crore for Los Angeles. The buyers told us to stop until further notice. With a 50 per cent duty, we can’t match Vietnam or Bangladesh. It’s like someone turned off the tap overnight,” said M Rajkumar, owner of a textile unit near Velampalayam in Tiruppur district.

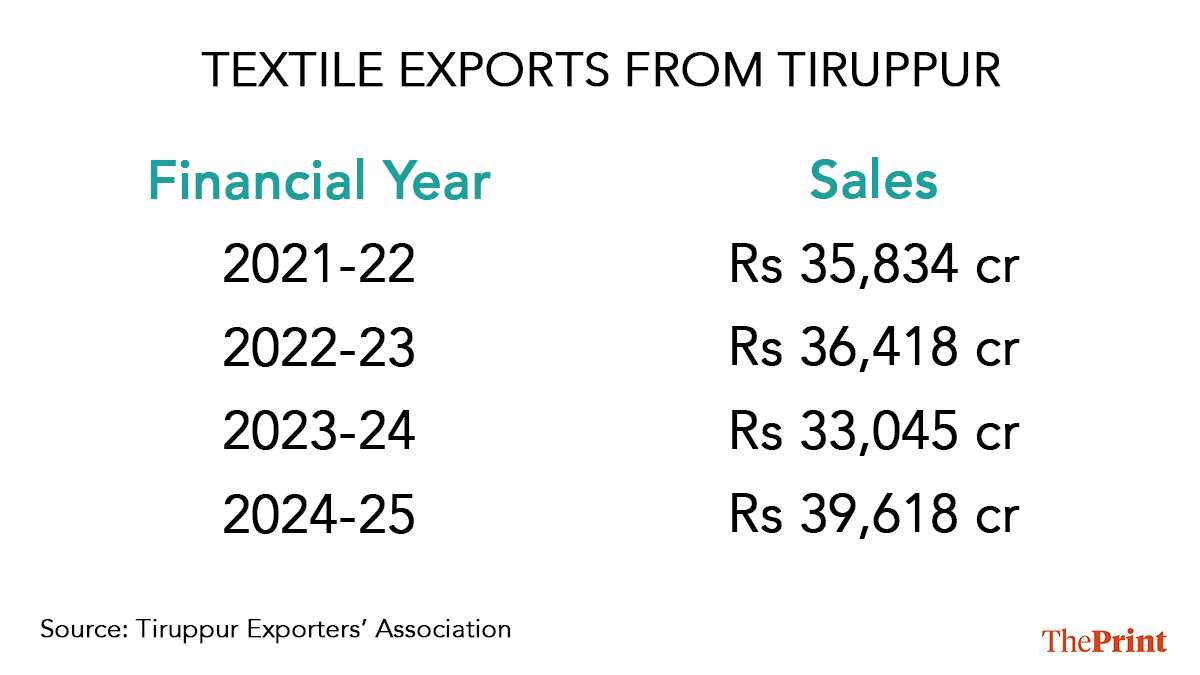

The United States is Tiruppur’s single biggest customer. The city produces 90 per cent of India’s cotton knitwear exports and about 55 per cent of total knitwear exports, according to the Tiruppur Exporters’ Association (TEA) website. In 2024-25, the city’s knitwear exports reached Rs 39,618 crore, up from Rs 30,690 crore the previous year. Among the total exports, about 30-35 per cent go to the US, making the city especially vulnerable to the new tariffs.

“Right now, those catering to the US market have not stopped production because orders were placed earlier. It is a cycle. You can’t just stop manufacturing midway. It starts from cotton candy and bales. If something has to be stopped, it has to start there, and the whole chain gets affected,” said TEA president KM Subramanian.

Buyers from ginning units used to call me before I even harvested the cotton. Now there is silence.

R Muthukrishnan, farmer

Tiruppur exporters are not in a position to accept the 50 per cent tariffs, since it would increase the price of the product drastically.

“Our margin itself is just 5-7 per cent. We cannot bear 50 per cent. If at all we have to, it will reflect on overall prices, and the end-users in the US will be affected,” Subramanian added.

Tiruppur’s textile export journey began in 1978, when an Italian buyer from Verona placed an order for plain white T‑shirts through Mumbai-based exporters. By 1981, European retailers had started visiting directly, and the town began to ship on its own.

In 1985, the total value of exports from Tiruppur was just Rs 15 crore. The climb since has been steep, with knitwear exports touching Rs 21,000 crore in 2014-15 and crossing Rs 34,350 crore in 2022-23. In the last fiscal year, it reached nearly Rs 40,000 crore, alongside Rs 27,000 crore in domestic sales. This puts the total trade volume at around Rs 67,000 crore.

Crisis in textile belt

For many exporters in Tiruppur, the fear is not losing the orders immediately, but losing long-term business. R Karthikraja, who has been in the textile business for over two decades, said that it was not just about one season and one order, but regular customers.

“We have regular buyers from the US who do not go to any other exporters even if there is a slight variation in the price of the textiles. But this 25 per cent hike in tariff threatens it. If those buyers move to a different exporter from a different country, it will be difficult to get them back, even if the issue is resolved sometime. It will take several decades,” Karthikraja said.

Exporters are being spammed with emails asking to hold their orders and seeking a revision of procurement prices. S Ramakrishnan, who owns a children’s wear shop in Tiruppur and supplies to an American buyer, said that he has been flooded with mails from seeking clarifications on previous orders, before putting them on hold.

“Mails from the buyers are not new, but now the questions have changed. It was us who were supposed to ask for the price revision, but they are asking for it. Apart from these 25 per cent tariffs, they are asking for a 10 per cent price reduction, which is way higher than our margins,” Ramakrishnan added. He is being asked to sell a product for less than its production cost.

Also read: Profit in NY, loss in UP—what Jane Street ‘market manipulation’ did to Tier 2 & 3 India

Exploring UK, EU markets

Exporters from Tiruppur are now exploring other options to compensate for the market value lost in the US.

KM Subramanian finds it a solace that the United Kingdom market has been opened for Tiruppur exporters after the UK–India Free Trade Agreement (FTA). The agreement grants India duty-free access for a wide range of textile and clothing products.

He views the possibility of exporting to the European Union with a mix of hope and concern.

“Compliance with EU guidelines will be a big barrier with the European market, like organic traceability, labour audits, and carbon footprint reporting. But we hope this also materialises and we manage to compensate for losses in the US market,” Subramanian said.

Small-scale industrialists who export to the US echo the view that it won’t be easy to divert exports to the EU.

“We meet US eco specs already, but the EU demands are longer and costlier. It’s not just one certificate; the chain is from farm to final box. Hence, it would be difficult for small and medium-scale exporters like us,” said S Gunasekari, a medium-scale industrialist.

Seeking overtime and a salary for it would look like a luxury, since the future does not look good. Our fingers are crossed. Hopefully, the industrialists would do something for the good of the workers.

S Vasudevan, spinning worker

The TEA is pushing for trade negotiations with the US. The association’s founder and honorary chairman, A Sakthivel, views quick relief as essential.

“If policy support takes years, many of our small members will not be able to bear the impact, and they will have to give up on the export and concentrate on the domestic market. However, domestic orders also will not be easy all of a sudden,” Sakthivel said.

Also read: Musk’s golden touch is on the line. Tesla needs him to do what he does best — sell a pen

Ripple effect in Coimbatore cotton mills

The impact of the tariff hike is not just confined to Tiruppur’s garment factories. It echoes far upstream in Coimbatore’s sprawling cotton mills and ginning units. The mills, which once operated at full potential day and night to meet the unrelenting demands of the knitwear units, are now grappling with an uncertain future.

A mill manager in Somanur at the border of Tiruppur and Coimbatore, S Harikrishnan, said that the industry has never come to a standstill except during the Covid-19 lockdown.

“We were piled up with orders earlier, and we used to work around the clock to meet the demand. Now, we are scared that we might return to the Covid days, as there will be very little orders from the knitwear companies,” said R Jagan, a mill manager in Somanur.

Cotton farmers in and around Coimbatore are also feeling the heat. R Mayilsamy, a farmer from Karur district in West Tamil Nadu, said that the cotton prices have already dropped by Rs 300 per quintal (100 kg) in the last month.

“If the price keeps reducing, there is no point in farming cotton. I would better move to maize next season. But it will hurt the mills if more farmers do so,” Mayilsamy told ThePrint.

In Tamil Nadu, the average price of cotton per quintal is roughly Rs 7,750, depending on the quality.

R Muthukrishnan, a farmer from Anthiyur in Erode district, said that the demand from ginning units has been slowing since Trump announced the 25 per cent tariff on 30 July.

“Buyers from ginning units used to call me before I even harvested the cotton. Now there is silence,” Muthukrishnan added.

Mill owners reflect the concerns of the farmers. K Selvaraj, general secretary of the Southern India Mills Association highlighted that it would be difficult for the entire industry if raw material is not available.

“Even if the orders bounce back later, farmers cannot bring up the cotton to match the demand, pushing us to purchase cotton from outside. Similarly, mills also cannot ramp up overnight, if the orders reduce now and increase later. It is a tricky situation,” he said.

Prabhu Dhamodharan, convenor at Indian Texpreneurs Federation, demands that the Union government negotiate with the US to remove additional duties.

“If the tariffs persist, a robust relief package, fearing moratoriums and a one-time working capital boost, will be vital to protect our operations,” Dhamodharan added.

Also read: New Gurugram to have New York-style Central Park, Disneyland. First fix roads, drains

Uncertain future for mill workers

The slowdown in Tiruppur’s garment units is already leaving a mark on workers’ lives.

Garment workers face an uncertain future, with ongoing talks of reducing their shifts. Many of them relied on overtime to pay their children’s school fees.

For R Dhanasekaran, a tailor at a garments unit, reduced work means reduced pay. “All the while, I was super busy and I know I have work for the next couple of weeks. But after that, even my company does not know if they will get the orders. And if the orders get reduced, my pay will also be reduced. My pay is based on the number of pieces I stitch on a daily basis,” he said.

The picture is more grim for migrant workers. Amit Kumar, a migrant worker from Bihar who stays with six of his friends in a small shed in Avinashi, has no other option but to return home.

“If the scenario is the same for all the units, it won’t be easy for us [migrant workers] to find a job in another unit immediately,” Amit Kumar said. He would prefer going back home rather than living on rent debt.

Workers at spinning mills in Coimbatore are also feeling the pinch. They just want to save their standard eight hours of work.

“Seeking overtime and a salary for it would look like a luxury, since the future does not look good. Our fingers are crossed. Hopefully, the industrialists would do something for the good of the workers,” said spinning worker S Vasudevan.

Senior knitwear workers recall the past slumps, including the 2008 financial crisis, demonetisation in 2016, GST rollout, and Covid-19.

“Each time, the industry adapted, shifted to domestic sales, found alternate buyers, and tightened the costs until the scenario returned to normal,” said R Kanagaraj, a 50-year-old knitwear worker.

From the first Italian export in 1978 to exporting knitwear worth Rs 40,000 crore in 2023-24, Tiruppur’s rise was built on the adaptability and relentless work by workers and industrialists. The question now is if the same adaptability can outpace a shifting global trade map before the looms go silent.

Sri Devi, a floor supervisor at a garments unit, doesn’t know what her future holds after the current orders are completed.

“With the Diwali festival coming in a couple of months, I am completely clueless about how we are going to make ends meet.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)