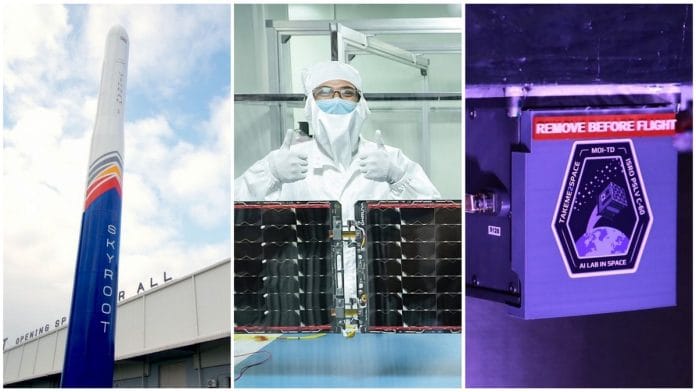

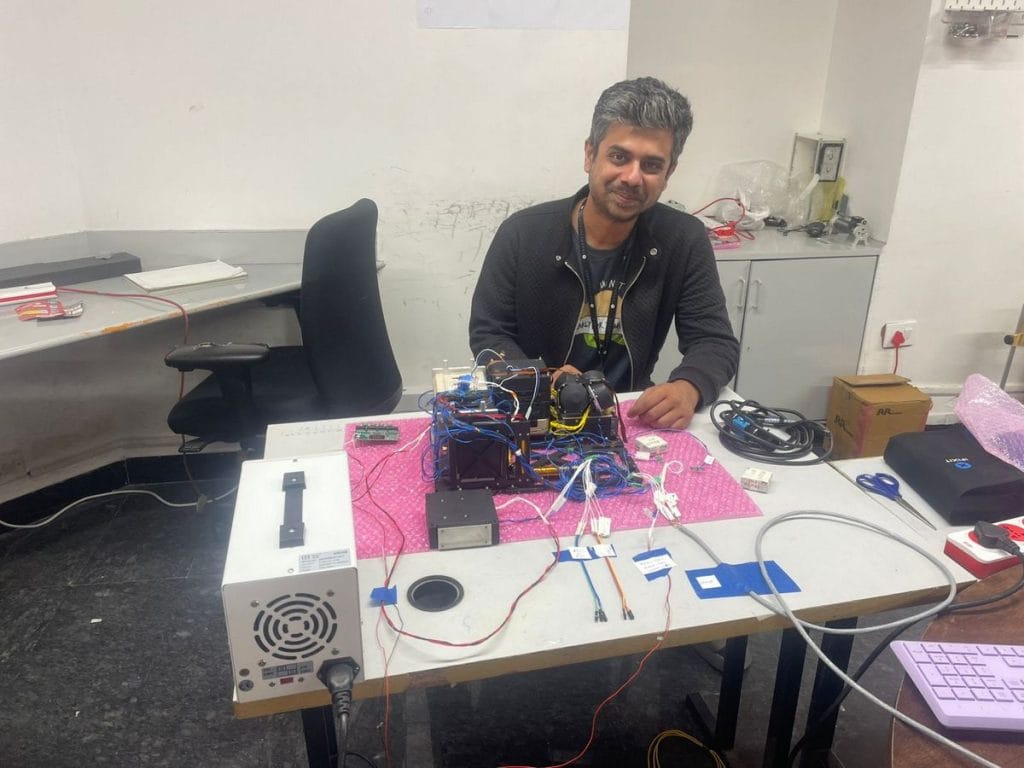

Hyderabad: In the middle of a makeshift laboratory littered with circuit boards, entangled wires, and rolls of duct tape sits an unfinished piece of machinery, waiting to be worked upon. Blue labels mark its onboard computer, electronic power system, and battery pack.

The contraption is destined for invisible horizons. It’s a satellite headed soon for Low Earth Orbit (LEO), where a new crop of Indian innovators is competing in a global race. LEO is now the most coveted piece of real estate in space. The Hyderabad satellite belongs to TakeMe2Space, which wants to democratise access to it.

“Growing up, we had access to computers. But today if someone wants to access a satellite, they’re asked to write a scientific paper,” said Ronak Kumar Samantray, the founder of TakeMe2Space. “We are creating a platform where any idea can be deployed in orbit.”

An entire wall in Samantray’s workspace at IIIT Hyderabad is painted black, with the company’s logo — three sides of a cube — next to the words ‘space is for everyone’. His plan is to build data centres in the sky, where computing will take place in orbit rather than on the ground.

Half a dozen graduates from IIT, BITS Pilani, and other engineering colleges are propelling India into the next frontier of modern spaceflight — satellites in LEO. Hyderabad is emerging as a hub, with Skyroot building the launch vehicles (rockets) and Dhruva Space offering full-stack solutions, from the satellite platform to the ground stations. In Bengaluru, meanwhile, Pixxel is building a constellation of satellites for Earth observation.

Sitting roughly 400 to 1,000 km above the planet, LEO is the easiest orbit to reach and is naturally shielded from intense radiation, making it a sweet spot for modern satellite applications. Consumers can access satellite internet with almost no lag, institutes can collect climate data, and scientists can get high-resolution images of agricultural land.

SpaceX is more like a train while we are like a cab. And the cab market hardly has any players

-Pawan Kumar Chandana, co-founder & CEO of Skyroot Aerospace

For decades, sending anything into space was an expensive endeavour, reserved for governments with deep pockets. That changed when Elon Musk’s SpaceX began flying its Falcon series of rockets, driving down launch costs by orders of magnitude. And the success of Starlink, SpaceX’s global satellite internet constellation, established LEO as the most lucrative segment.

“Just like our smartphones are getting smaller and more efficient, so are satellites. Launches have also become more frequent and cheaper,” said Pawan Kumar Chandana, the co-founder and CEO of Skyroot Aerospace, in between meetings gearing up for the launch of Vikram 1, their first rocket aiming to reach LEO.

“And three billion people don’t have access to high-speed internet. To connect them all, space is the best — it’s global.”

Also Read: India’s $44 billion space dream rests on getting SATCOM right

India’s satellite assembly line

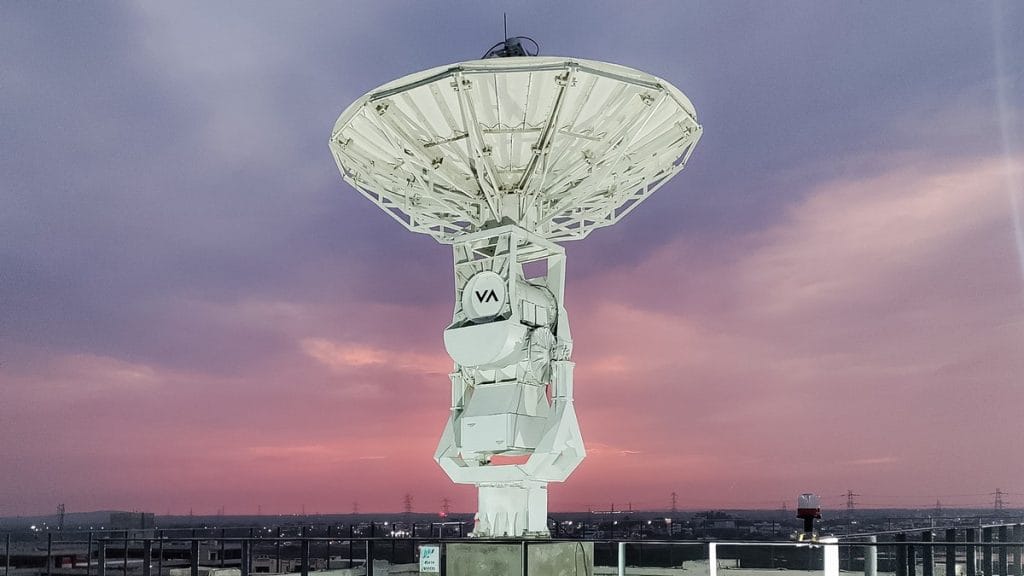

In a room perched above the rest of their office in Begumpet, Hyderabad, Dhruva Space tracks aggregate data from 300-odd satellites. Large monitors display multi-coloured maps of the earth, where archived imagery can be accessed in different resolutions.

Displayed proudly on a table is a black cube with four antennas that can fit in the palm of a hand. It’s the P-DoT, Dhruva’s smallest satellite platform. The company is trying to capture all three pillars of any satellite mission: space, launch, and ground.

“We realised that the world is moving away from building one, three, ten satellites to hundreds and thousands of them,” said Sanjay Nekkanti, the founder and CEO of Dhruva, as he reminisced about his 13-year journey. “If India were to build 1,000 satellites, there needs to be infrastructure in place to achieve this.”

On the space segment, Dhruva is already building platforms across different mass categories and “working toward a 500-kg class platform”. Each is suited to a different function.

Dhruva doesn’t try to do everything in each pillar, but its strengths lie in building the connective tissue of a full stack space engineering solution.

“We built the building blocks, but we don’t build the payloads on our satellites,” said Nekkanti. Cameras, for one, aren’t part of their expertise, but he points to his phone to show how hardware is more than the sum of its parts. “Think of the iPhone. The camera isn’t made by Apple. But for the whole system to work — the software, the electronics, the packaging — somebody has to put everything together.”

Go back in time and picture a 22-year-old saying, ‘I’ll build a satellite.’ It was tough. But the government understood the need for the market to open. The rest of the world was already doubling down

-Sanjay Nekkanti, founder & CEO of Dhruva Space

On the launch front, Dhruva doesn’t build rockets, but it has developed a ‘uniform separation system’ — a one-size-fits-all approach — that allows its platforms to fly on different rocket designs, whether from US-based SpaceX or India-based Skyroot and AgniKul.

Finally, the ‘ground’ pillar means having a global network of stations to access satellite data. Dhruva now runs some ground stations itself and also plugs into existing ones worldwide.

“Satellites go around the Earth in 96 minutes — so they’re collecting a lot of data. And the maximum contact time you can establish with it is a 14-minute time window,” said Nekkanti, turning his swivel chair as he explained the point with a flair that seemed born of delivering the pitch at many investor meetings.

On their journey to capture the satellite value chain, the company also started making high-quality, space-grade solar panels. Up to 30 per cent of a satellite’s cost is the power system, which includes the solar arrays and batteries.

“If you’ve built the engine of car already, it becomes a question of opportunity on whether you want to capitalise on it,” said Nekkanti.

It wasn’t part of the original plan but fit into a broader strategy.

In India, he wants Dhruva to be an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) but in global markets, he wants to supply other OEMs.

“Our objectives have always been aligned with that of India. The government wants to increase India’s share in the global space tech market,” he said.

This is where India’s private space tech companies have struck gold — selling indigenously made subsystems to global players.

At TakeMe2Space, Ronak Kumar Samantray calls it his “cash cow”. His website resembles an e-commerce page for satellite equipment, complete with prices and add-to-cart buttons. A battery pack sells for Rs 1,04,900, and an onboard computer is priced at Rs 8,20,190. A 16U CubeSat Bus goes for over Rs 2.8 crore.

Samantray jumps out of his seat to grab a motor from across the cluttered room.

“This is the wheel, which orients the satellite. Like this, there are 24 satellite hardware products on our website,” he said.

Other Indian space start-ups, including GalaxEye Space and N Space Tech, purchase his products.

Holding up the wheel, Samantray said that the cheapest available substitute from France is priced at Rs 15 lakh.

“I sell it for Rs 5 lakh, but I won’t tell you my cost price,” he said, laughing.

What’s the payoff?

The headquarters of TakeMe2Space looks more like a high school science lab than a deep tech start-up. Tables overflow with glue guns, plastic bins filled with satellite parts, and sheets of bubble wrap. In this single cramped space, the entire satellite is assembled.

“A satellite of our size would easily cost Rs 6 to 7 crore, which we have brought down to less than Rs 1 crore,” said founder Samantray, proudly gazing at his creation. “We designed and manufactured all the satellite subsystems ourselves, which helped us reduce cost.”

When it comes to cost, computing the data is only a few cents. The costliest part is downloading that data from a satellite. By having a lab in orbit, we process the data up there. Customers only download the inferences

-Ronak Kumar Samantray, founder of TakeMe2Space

He powers up his laptop to show his main product — OrbitLab. A digital map of Earth pops up, tabs and data points across it. Customers use the platform for everything from agricultural monitoring to construction tracking.

At Rs 250 per minute, OrbitLab is attempting to disrupt the segment by beating the lowest prices in the market. And the secret sauce lies in not just building the satellite in-house but also computing the data up in the sky.

“When it comes to cost, computing the data is only a few cents. The costliest part is downloading that data from a satellite. By having a lab in orbit, we process the data up there. Customers only download the inferences,” Samantray said.

His satellites don’t have high resolution capabilities, which are usually used for surveillance by governments. But private companies don’t want to capture the leaves on a tree. They just want to check whether mineral signatures exist or if agricultural land is receiving enough rainfall.

LEO’s conditions also help drive down costs. The orbit sits inside a magnetic shield that protects satellites from the worst of solar radiation, and the temperature is conducive to automotive- and industrial-grade components — TakeMe2Space doesn’t use any space-grade parts.

“We have done two 45-day space missions already, and two more satellites are going up this year,” said Samantray, adding that apart from his own money, the company has raised Rs 5 crore from external investors. “Next year, we are putting six satellites in orbit.”

Across town, Skyroot Aerospace is scaling rapidly too. In 2023, it inaugurated a 60,000 square-foot headquarters at the GMR Hyderabad Aviation SEZ. The sleek facade flaunts an astronaut sculpture mounted high next to the logo; the wall is painted black and dotted with white for a star-speckled look.

“Instead of having one big satellite in geostationary orbit, you can now have a network of thousands of satellites in LEO. It’s kind of similar in economics, and you can cover the entire globe,” said Pawan Kumar Chandana, after a quick meal at the fully serviced cafeteria on the top floor.

After raising nearly $100 million from local and foreign investors, Skyroot is aiming to become the first private Indian space company to send a rocket to LEO. It’s their biggest leap after the successful launch of Vikram-S to sub orbit in 2022.

Chandana said the energy needed to reach Low Earth Orbit is several orders of magnitude higher than what it takes to fly a sub-orbital mission. “When you reach sub orbit, around 80 km from Earth, the velocity of the rocket is zero. That’s why it falls back,” he said. “And you have to insert a satellite at almost 8 kilometres per second.”

He compared Vikram-S to a two-storey building and Vikram-1 to a seven-storey one that’s nearly 100 times heavier. The LEO-bound rocket also has three core stages and a kick stage, compared to the single stage of Vikram-S.

“Complexity and cost wise, it’s a lot higher than our maiden launch,” he added.

It costs about $2 million for Skyroot to put a rocket into space, but Chandana said a single launch can generate up to $10 million in revenue, depending on the customer and their required orbit. And it offers something different in a market dominated by SpaceX.

While SpaceX sends large payloads to fixed orbits, Skyroot offers more flexibility, allowing customers to choose the optimal orbit for specific regional coverage.

“SpaceX is more like a train while we are like a cab,” said Chandana. “And the cab market hardly has any players, except for [California-based] Rocket Lab, which is a pioneer in this field.”

Also Read: Startups to govt policies—India wants to lead the lab-grown meat revolution

Who are the founders?

Chandana is no stranger to rocket science. A former ISRO engineer and IIT-Kharagpur alumnus, he had worked on launch vehicles before co-founding Skyroot in 2018 with fellow ex-ISRO engineer Naga Bharath Daka, an IIT Madras graduate.

Talking about the hurdles ahead of the Vikram-1 launch, Chandana stays remarkably composed. The soft-spoken, bespectacled engineer breaks down each roadblock with the ease of someone who has learned to mentally sort and file every setback that comes with building a space company.

“Even if one system doesn’t work, you can get stuck for years,” he said nonchalantly in between bites of biscuits at the Skyroot office. “For example, the thrust vector control system which steers the rocket. It took much longer time than we expected.”

As someone who began his career in the government space agency, Chandana still speaks with deep respect for the public institutions that shaped him. He credits much of the private sector’s progress to ISRO, whose facilities Skyroot continues to use for propulsion tests, engine tests, assembly, and launches.

In 2020, the Government of India set up IN-SPACe (Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre) to spur private participation in the sector. Its headquarters in Ahmedabad was inaugurated just five months ahead of the launch of Vikram-S in November 2022.

I was always clear on doing full stack solutions, so when we started looking for capital in 2017 it was tough to convince investors. We got lucky on the 163rd investor

-Sanjay Nekkanti, CEO of Dhruva Space

“The first private rocket launch in India was ours. Normally, authorisation takes years. But IN-SPACe ensured all the paperwork and procedures were done,” Chandana said.

Thirty kilometres from Skyroot’s office, the Dhruva Space headquarters offer a visual reminder of how far India’s private space industry has come. Past mission emblems decorate one wall, opposite a ping pong table.

Founded in 2012, Dhruva was one of the earliest entrants in India’s private space sector. But those early years were anything but easy, according to founder Sanjay Nekkanti, an electronics and telecommunications graduate from Tamil Nadu’s SRM University.

“Go back in time and picture a 22-year-old saying, ‘I’ll build a satellite.’ It was tough,” he said. “But the government understood the need for the market to open. The rest of the world was already doubling down.”

Between 2017 and 2019, Nekkanti was joined by long-time friends Chaitanya Dora Surapureddy, Abhay Egoor, and Krishna Teja Penamakuru — all BITS Pilani graduates who are now Dhruva’s co-founders. All four and their families even hang out outside work.

“I was always clear on doing full stack solutions, so when we started looking for capital in 2017 it was tough to convince investors,” Nekkanti said, smiling as he looked back at the confidence — or sheer audacity — of his 27-year-old self. “We got lucky on the 163rd investor.”

Ronak Kumar Samantray knows a thing or two about investor rejections too. TakeMe2Space isn’t his first start-up. He previously co-founded NowFloats, a local discovery platform for small and medium businesses, after a degree in computer science from Bhubaneswar’s College of Engineering and Technology, and a short stint at Microsoft.

After Reliance Industries acquired NowFloats in 2019, Samantray began looking for a sector that would matter ten years ahead.

“I never decide on one sector, always an array of sectors,” he said, words tumbling out as he explained his decision-making matrix. Space, quantum computing, humanoids, and CRISPR (gene-editing technology) are what he narrowed down to. “Everybody’s brother and mother was working on SaaS (software as a service).”

Space stuck but he needed to narrow it down. As he watched other new players such as Skyroot and AgniKul, satellites seemed like a good bet. But the actual business idea came from a sense of irritation. Even as an engineer who could code and had the money, he couldn’t get his hands on a satellite.

“And they said humans will become a space-faring species,” he said, frustration seeping into his voice. But Samantray, who exudes the confidence of a part-rebel, part-tinkerer, couldn’t take no for an answer.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)