Varanasi: In a house wedged in the lanes of Sarnath, a group of people is racing to give just dues to very special red kidney beans—Jammu and Kashmir’s Gurez Rajmash. The documentation has to be done perfectly for it to get the coveted Geographical Indication tag. Watching it all with hawk eyes is a man with long grey locks, a moustache to match, and faded vibhuti on his forehead. He is Rajni Kant, the GI man of India.

The 65-year-old isn’t happy with the photos being uploaded by his assistant. “Remove these blurred images,” he said, before stepping up to the computer himself to choose better ones showing the mountain slopes where the beans are grown.

Rajni Kant is spearheading the GI tag wave in India from Varanasi. He is the go-to man for all GI tag applications in India today. He knows the rules, the process, and paperwork for getting the much-sought-after label. And he has combined his passion for Indian heritage with the need for creating globally recognisable, marketable identities for traditional products. His journey started with Vajpayee and continues with Modi, and he proudly points to photos of both in the cluttered notice board in his office.

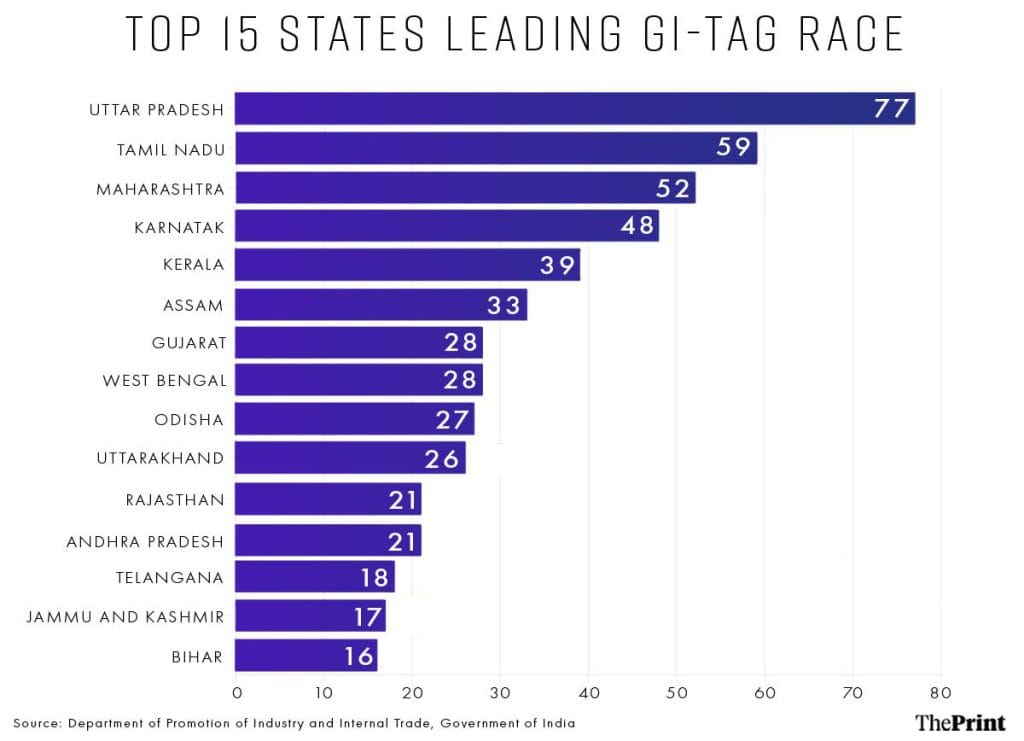

In the last two decades, more than 600 products have got the GI tag in India, and Uttar Pradesh leads the list with 77. Since 2014, Varanasi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s constituency, has become the biggest GI facilitation centre. Back in 2013, only Banaras brocade and Bhadohi carpets had the GI tag in the region. Today, there are 32, from Varanasi Gulabi Meenakari craft and Banaras glass beads to wooden lacquerware, Zardozi, Lal Peda, Banarasi Thandai, and Tirangi Burfi.

“In Varanasi we have created a model for securing GI tag. Now this model has been replicated across India, from Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh to Uttarakhand. Our efforts bring change on the ground,” said Kant.

He’s a leading light in the Modi government’s mission to secure 10,000 GI tags by 2030. Even before Modi’s slogan of “Vikas bhi, Virasat bhi”, making development and heritage walk hand in hand has been the principle guiding his work. He is known locally as ‘Kashi Gaurav’—the pride of Kashi. A postgraduate in agriculture, he moved into social welfare after watching skilled craftspersons barely keep their heads above water, especially once foreign brands flooded post-reforms India. He started the Human Welfare Association (HWA) in the 1990s and soon helped make Varanasi the country’s GI capital.

With Modiji’s inspiration I have started working in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jammu Kashmir, Assam, Bihar, Andaman and Nicobar

-Rajni Kant

Kant’s model has spread nationwide, empowering lakhs of artisans and reviving heritage industries. States such as Arunachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Gujarat have sought his help. With support from state governments and the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), he’s helped make their GI-tag dreams come true. He has worked in 30 states, filing 496 GI applications, of which 159 have been granted by the Geographical Indications Registry in Chennai.

“I’m helping all the states of the Northeast. The GI tag for 34 products in Arunachal is in process,” he said.

A Geographical Indication (GI) tag is a legal certification that establishes that a product originates from a particular place, such as Champagne in France or Parmigiano Reggiano in Italy. The idea is to deter counterfeits and ensure that makers in that region get due credit and better prices.

“I’m preserving India’s cultural heritage. Lakhs of people are dependent on these. When we say India was once sone ki chidiya, it’s not because of gold but the regional heritage and art. Over the centuries we’ve lost that. The GI tag is giving a new lease of life to products that had lost their charm,” said Kant, showing a photograph of himself with PM Modi at an event in Varanasi.

While questions remain about whether a GI-tag alone can ensure sustainable markets, Kant said the push has boosted Varanasi’s MSME sector, especially “in craft, cuisine and culture.”

Modi has made GI-tagged products a showpiece of his Vikas bhi aur Virasat bhi framework, often gifting them to foreign leaders. During a visit to Mauritius this year, he presented President Dharambeer Gokhool with an ornate metal pot made of GI-tagged Banaras metal casting craft. In April, the PM gave GI certificates to 21 products in Varanasi, including Shehnai and Lal Peda.

“When a GI tag is granted, it opens the path to greater market heights,” said Modi at the certificate distribution event. “Today, Varanasi products have received a new passport.”

Also Read: Whose Pisco is it anyway? How Delhi HC put to rest Chile-Peru dispute over GI tag for grape brandy

GI tags from ‘Kashi to Kala Pani’

The journey of UP becoming the number one in GI tagging in India runs parallel to the personal journey of Rajni Kant.

In 2007, UP had only one GI product, the Allahabad Surkha Guava. Now the number has increased to 77, including Sambhal Horn Craft, Kalpi Handmade Paper, and Gorakhpur Terracotta. But it was not an easy task to achieve this number.

When Kant started working on GI tag, he had no knowledge of this field. Born in Jalalpur Mafi village of Mirzapur district, he was doing his PhD in Banaras Hindu University when he was drawn to social work. In 1991, he founded the Human Welfare Association, focusing on women’s empowerment and skill development. The timing coincided with liberalisation. As economic reforms swept India, there was a craze for all things foreign as multinationals entered the country. He grew alarmed.

“I saw the foreign products make a large space in the Indian market resulting in poor condition of the local artisans,” he said. He knew he had to do something but wasn’t sure what. “I’m fortunate that God chose me to work for the people who are the pride of this country. But at that time I had only heard about Intellectual Property Right.”

It was a meeting in Lucknow with former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee that changed his life in 1999. He had finally found a willing ear.

“I raised my concern related to protecting the community products. After 15 days, officials at the commerce department called me to Delhi to discuss these issues,” said Kant, sitting at his office in Sarnath with the walls full of images with Narendra Modi, Manmohan Singh, Amartya Sen, APJ Abdul Kalam.

Four years later, in 2003, India implemented the GI Act, registering Darjeeling Tea as the first product. While Kant was not involved with the law’s drafting, he was quickly convinced that it could be the answer to artisans’ woes in Varanasi. He homed in on the Banarasi Saree for GI tag registration, but to his surprise the trade association was resistant.

In the last one decade we have witnessed that the number of applications from UP, especially from the Kashi region, have increased. Behind all these applications, the person is the same

-Official at the GI registration office in Chennai

“They didn’t know about the GI tag. They thought I’m filing a patent for the product,” he said. It took years to convince them but in 2007, the application was filed. “By 2009 we got the GI tag.”

The GI didn’t dramatically alter the fortunes of the weavers but it did open the door to a new form of recognition for products that were not quite as well known.

“Banarasi Sarees were famous already. Across India they have demand. But as it’s one of the premium products of Banaras, so it was chosen for applying GI tag initially,” said Zubair Adil, secretary of Bunkar Udyog Mandal, a weavers’ association in Varanasi.

For Kant, that first registration turned into what he calls his “identity” and “full-time job.” Support from the government has ramped up in the past decade, and he has travelled to international expos in Indonesia, Singapore, and Germany to promote these crafts.

“Now through NABARD, we are getting funds for working on the applications for GI products,” he said. He declined to specify the quantum of funds other than saying it was “sufficient”. A NABARD factsheet says its GI project in Uttar Pradesh—implemented through the Human Welfare Association—had a total outlay of Rs 16.13 million (Rs 1.6 crore).

Until six years ago, he focused on Varanasi products such as wooden toys and meenakari but then a nudge to branch out came from the PM himself. This was after Kant had been awarded the Padma Shri in 2019 for his work in uplifting the lives of artisans and weavers.

He recounted that during one of his visits to Varanasi that same year, Modi told him: “Ab aap Banaras se bahar bhi sahyog kijiye”—help us in this work outside Varanasi as well.

He did just that, starting with Uttarakhand in 2019.

“With Modiji’s inspiration I have started working in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jammu Kashmir, Assam, Bihar, Andaman and Nicobar,” said Kant, adding that these initiatives involve working closely with district administrations.

From J&K’s Rajouri Chikri Wood Craft to Rajasthan’s Nathdwara Bandhej to Nicobar Coconut, he described it as “Kashi to Kala Pani” impact.

How does the process work?

Kant’s team of about twenty people works from a long hall in Sarnath, its walls covered with GI certificates, awards, and photographs from his travels. A few computers sit beside an old wooden shelf stacked with Arthashastra, Ramcharitmanas, and Upanishads. He often trains delegations from other states there, explaining how to build a case for a GI tag.

When a state government approaches Kant, his team’s first move is to do a deep dive into the product’s history and provenance, whether it’s through ancient Indian texts or Mughal paintings. Kant has put together a network of people in every state who conduct research for him and travel. At a riper stage in the process, he also visits the region in question.

Recently, his team filed for Ladakh’s Challi textile, tracing its roots through Kautilya Arthashastra and an 11th-century monastery painting.

“India has a long tradition of making cloth. Ladakh is on the route between Magadha and Taxila chosen by Chanakya. I got a hint from that book about Challi technique. We mentioned that in our application to describe its origin,” said Kant. He added that Challi textiles are in the final stages of receiving a GI tag.

His team has already secured recognition for 18 products from Arunachal Pradesh, such as Idu Mishmi Textile, Monpa Carpet, and Aalo Bamboo Craft, with more in the pipeline. The governor of Arunachal Pradesh felicitated him on Statehood Day this year, and the Arunachal University of Studies awarded him an honorary Doctor of Literature.

Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath told me to work on 75 more products for GI tag — one from each district. We are identifying the products now. Very soon, we will file applications for all

-Rajni Kant

The GI registration process comes under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, and it is usually long and exacting. Applications require documentation proving a product’s history and geography, and many get stuck at the registry in Chennai when applicants can’t provide adequate evidence.

Obtaining a GI tag can sometimes take the better part of a decade. For Kannauj attar, it took five years to collect the necessary documentation to prove its origins. Mithila makhana, which got the tag in 2022, took four.

Each application is eventually reviewed by a registrar and a panel of experts across disciplines. Applicants must present their case before the committee, which decides whether to grant the tag.

Across the country, dozens of products are waiting—34 from Arunachal Pradesh, 24 from Tripura, 10 each from Assam and Bihar. Among them are Surat diamond, Patan textile, Ayodhya Hanumangarhi Laddu, Mathura Peda, Aligarh metal statue, Nalanda Bawanbuti, Darbhanga terracotta, and Hajipur Chiniya Kela.

Each year Kant challenges himself. In the Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsava year, he filed 75 applications. The next year, in 2023-24 he filed 100 applications. Of all the applications Kant has filed, about one-third have been approved. The rest are being processed; none have been rejected.

“In 2024-25, I have set a target of filing 75 applications. This target was set on the birthday of PM Modi in 2024. On 17 September 2025, on his birthday, I filed the 75th application, of Sompura stone craft from Gujarat. It was a gift to Modiji from us,” said Kant.

Varanasi’s GI blitz

On the wall of Uday Shree Misthana, a humble sweet shop near UP College in Varanasi, hangs a framed GI certificate. In April, proprietor Kamlesh Kumar received the tag for Lal Peda, a khoa-based sweet; it’s registered under the milk product category.

Kumar is the sixth generation in his family to make Lal Peda.

“My ancestors started making it. After centuries, this sweet delicacy got its recognition,” he said, while packing boxes for customers. He says sales have increased since the tag; three trays of pedas disappeared within half an hour. “Rajni Kant contacted me in 2022 for the GI application. Through his efforts, we have got this tag. What he is doing for the city, no one can match,” said Kumar.

There has been one troubling side effect though. Kumar complained that since the GI tag, a number of shops have opened, each claiming to sell the original Lal Peda. It’s joined the ranks of other long-standing staples, including Thandai, Lal Bharwamirch, Adamchini rice, Langda mangoes, and Banarasi paan.

Kant’s team is also working on other products, such as Banaras Launglata and the city’s traditional boats.

“Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath told me to work on 75 more products for GI tag — one from each district. We are identifying the products now. Very soon, we will file applications for all,” Kant said.

Only 25-30 people were pursuing [Gulabi Meenakari] in 2011. Now hundreds are working. It’s all because of the GI tag it got in 2015. Those who left the work joined again and we have enough orders for the year

-Arun Kumar, artisan

The GI movement has strengthened the city’s economy by opening new channels for trade and visibility, according to him.

Many textile expos and GI Mahotsavs have been held in the past few years, with traders and artisans participating and getting orders from there. It’s cast a spotlight on edibles and crafts that were barely noticed before. For exports too, traders now use the GI tag to signal their authenticity.

Through 32 GI-tagged products, about two million people are connected directly or indirectly, Kant said.

“The annual turnover from these products is Rs 25,500 crore. It will only add up in the future,” he added.

Every year, the GI Registry in Chennai gets dozens of applications and Kant is the man behind many of them.

“In the last one decade we have witnessed that the number of applications from UP, especially from the Kashi region, have increased. Behind all these applications, the person is the same,” said an official at the GI registration office.

When it’s time to present the product before a panel of experts, Kant himself does the job, often taking artisans or traders along. Using PowerPoint slides, he briefs officials on the product’s originality, geographical link, and documentation. For example, in the case of Lal Peda, he included details such as specifications, qualitative characteristics, composition, maps of production areas, and historical references from books.

“What we have seen in the case of Kant is that he comes with strong research work and arguments. His thoughts are clear, which eases the process of giving the certificates,” said the official.

Also Read: Does GI tag bring more business? Mysore silk & Jardalu mango rose, not Kannauj attar

Has GI tag brought new riches?

For all the celebration around Varanasi’s GI boom, the results have been uneven. Some crafts have received a tangible boost, while others still struggle to turn recognition into real income.

One of the success stories is Gulabi Meenakari, a Mughal-era art of hand-painting pink enamel designs on metal surfaces. In the narrow lanes near Kal Bhairav temple, artisan Arun Kumar and his family have practised this delicate craft for generations but it was dying.

“Only 25-30 people were pursuing this craft in 2011. Now hundreds are working. It’s all because of the GI tag it got in 2015,” he said, showing a chessboard of pink enamel on white metal.

The tag, secured with NABARD’s support, helped bring the art into mainstream markets, especially with PM Modi himself gifting artefacts to dignitaries. In 2021, he gifted a Gulabi Meenakari chess set to then US vice-president Kamala Harris. The GI melas helped too.

“Those who left the work joined again and we have enough orders for the year,” he said, adding that recent buyers include customers in Gujarat and Dubai.

Not every product has fared as well. Varanasi’s wooden lacquerware and toys, tagged in 2015, continue to struggle.

“We got recognition for our art but not the market,” said Rameshwar Singh, who runs a small workshop making brightly painted wooden toys. “We are invited for expos and melas across the country and get some orders through them, but to expand our business there are no good facilities.”

To scale up and reach more customers, they need more than a nod in their direction. Singh said one weak link is packaging.

No one is paying attention to the post-GI registration mechanism. There is an institutional lacuna. A framework must be created to take full advantage of the tag, and for this awareness programmes are needed

-Mohit Sharma, assistant professor at Dr Rajendra Prasad Agricultural University

“Customers need good packaging of the product. We fail at that. The government should help with better packaging so we can sell our products in a world-class manner and earn profits.”

Economists and industry experts have long voiced similar concerns. A GI tag alone can’t revive a product, and the government must apply more life-saving measures.

“No one is paying attention to the post-GI registration mechanism. Before getting a GI tag, market acceptability has to be studied, and for this, a market channel needs to be created,” said Mohit Sharma, assistant professor at Dr Rajendra Prasad Agricultural University in Samastipur. “There is an institutional lacuna. A framework must be created to take full advantage of the tag, and for this awareness programmes are needed.”

NABARD data shows that the “average turnover per year” is Rs 1,500 crore for Banaras brocades and saris, Rs 15 crore for Gulabi Meenakari, Rs 5 crore for Banarasi lacquerware and wooden toys, and Rs 100 crore for Banaras metal repousse craft. However, it does not specify the period over which these averages were calculated or provide any year-on-year figures for comparison.

In its factsheet on Varanasi GI objects, NABARD claims there has been a “40-200% increase in annual income of artisans, weavers, and farmers” since GI registration, but no further specifics.

Kant is sanguine about the fruits of the GI tag being reaped later if not sooner.

“It’s just a starting point for many products,” he said. “Decades of neglect will take time to come on track. The Varanasi GI journey established that the tag can boost economy and it’s not just a piece of paper.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)