Cuddalore: Every morning at 8 am, E Balaji grabs his lunch bag, heads out from his home in Cuddalore district’s Kudikadu village, and boards a wooden boat for a roughly 10-minute ride to a once-barren island on the Uppanar River’s backwaters. He’s on a critical mission: to protect 37,000 delicate mangrove saplings from cattle and other threats. One day, these trees will repay the favour, standing as a natural fortress against floods and erosion.

“Sometimes, I bring my father too. This is not a one-man job,” said Balaji sitting under a makeshift bench under a tree. For the 27-year-old fisherman from the Vanniyar community, these saplings, spread across 25 hectares, have consumed most of his days since August 2023. What used to be a barren grazing ground is now transforming into a mangrove ‘bioshield’—designed to protect nearby villages from floods and disasters, while also revitalising the local marine ecosystem.

The relationship between the villagers and the mangrove is symbiotic. As they nurture the plants, the plants offer employment, ecological safety, and a more climate-resilient future. While Balaji oversees the protection of the saplings—monitoring their health, keeping bovines at bay, and ferrying officials to the island—about 20 other villagers have been assigned tasks like planting and desilting. And it’s not just this island.

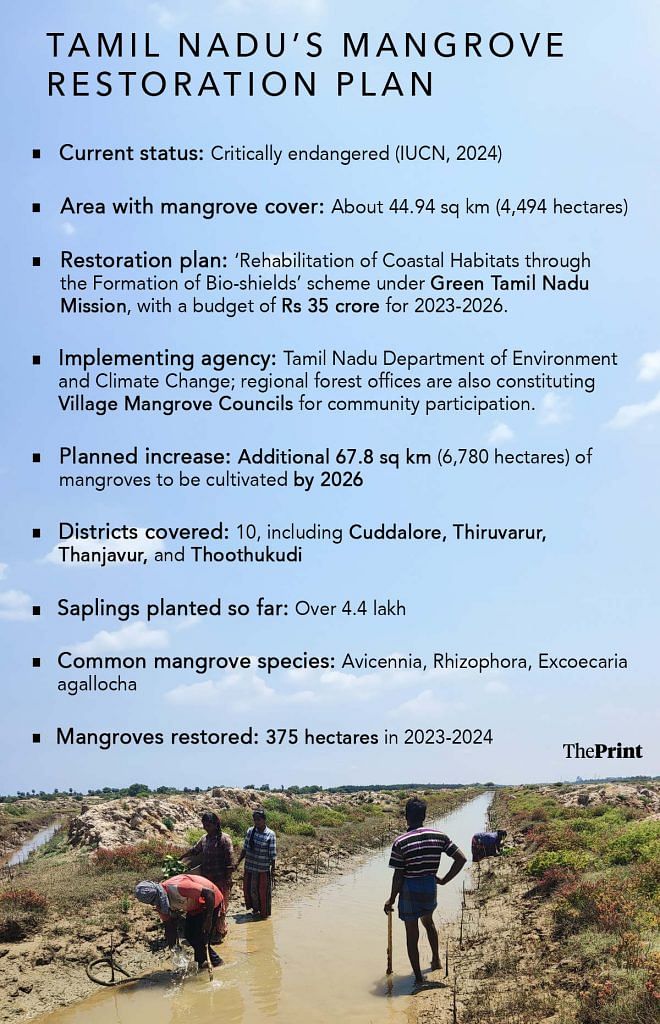

As part of the Green Tamil Nadu Mission, the state government is establishing ‘bio-shields’ across 10 coastal districts, including Cuddalore. The Department of Environment and Climate Change has allocated Rs 35 crore to implement the ‘Rehabilitation of Coastal Habitats through the Formation of Bio-shields’ scheme, launched last year.

“The state government’s strategy is to find new areas for mangrove forests and restore the degraded ones,” said Deepak Srivastava, additional principal chief conservator of forests and member-secretary of the Tamil Nadu State Wetland Authority.

The goal is ambitious: expand Tamil Nadu’s mangrove cover by adding 67.8 square kilometres to the existing 44.94 square kilometres by 2026. This target has become even more urgent after the devastating floods last December in the coastal districts of Thoothukudi, Tirunelveli, Tenkasi, and Kanniyakumari, coupled with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) designating the state’s mangroves as ‘critically endangered’ this May.

The purpose of (Village Mangrove Councils) is that they give a sense of ownership to villagers. If they get involved in planting, they will also protect the mangrove

– Deepak Srivastava, additional principal chief conservator of forests

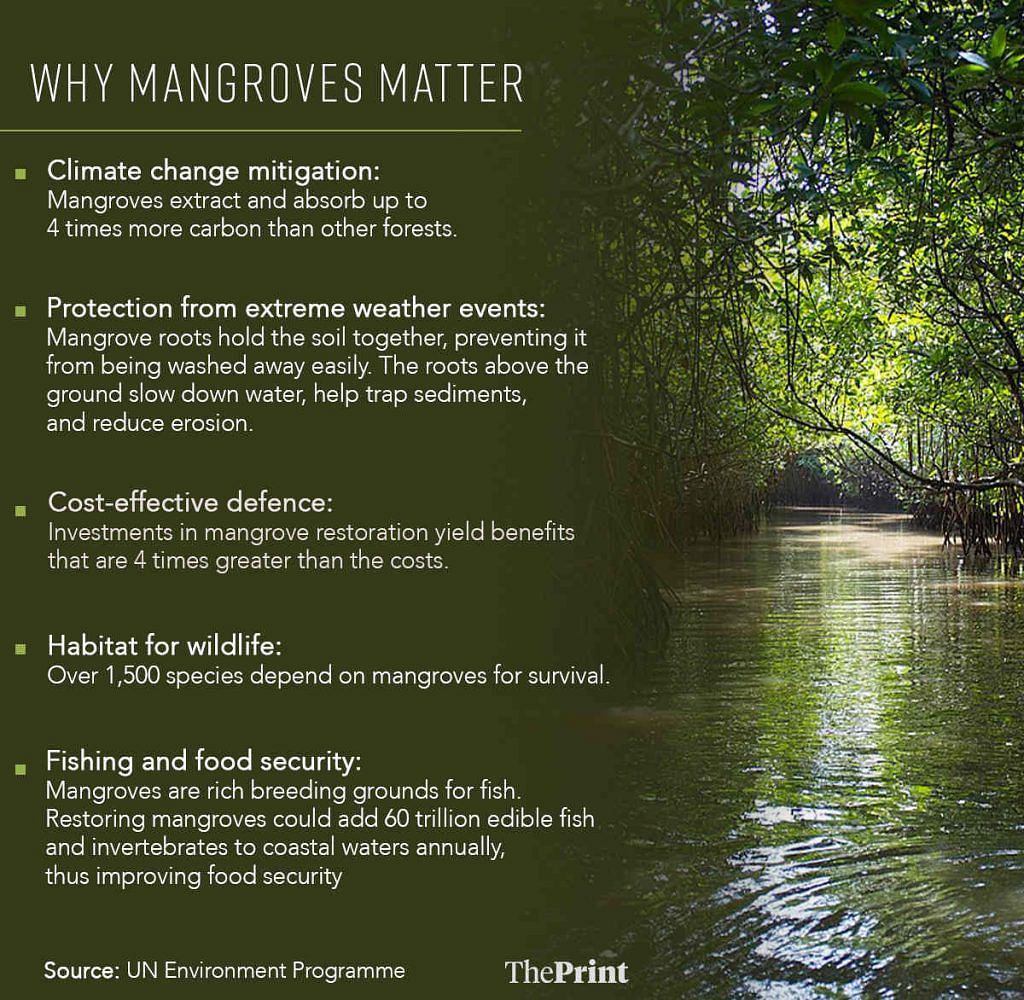

Mangroves, which cover about 30 per cent of India’s coastline, are the first line of defence against cyclones, floods, and coastal erosion. But over the last century, India has lost 40 percent of its mangrove cover, now at around 4,975 square kilometres, according to the 2021 Forest Survey Report. Both the Centre and several state governments have stepped up their efforts to revive mangroves. In 2022, India joined the Mangrove Alliance for Climate at COP27, and last year, the Union Budget allocated over Rs 3,000 crore for the ‘Mangrove Initiative for Shoreline Habitats & Tangible Incomes (MISHTI)’ scheme.

State governments are also driving restoration initiatives, with varying degrees of success, from the Sundarbans in West Bengal to the Krishna-Godavari belt in Andhra Pradesh. But it is Tamil Nadu that has been leading the charge with its afforestation projects, including for mangroves. Over three years, its modest mangrove cover has reportedly doubled, according to a geospatial mapping exercise this year by the Tamil Nadu Biodiversity Conservation and Greening Project.

But experts worldwide agree that the success of mangrove projects hinges not just on scientific cultivation and government funding but on community involvement, knowledge-sharing, and residents’ active participation. The Tamil Nadu plan recognises this.

“Whenever the whole of Tamil Nadu was reeling under floods, the villages surrounding the mangroves were less affected,” said A Aruldoss, a forester at the Pichavaram Forest Range monitoring the works at Kudikadu. The villagers tell us how important it is to save this ecosystem and we are learning from them too.”

Earlier, Balaji relied solely on fishing to make a living, earning about Rs 500 a day. Now, he makes Rs 800 as a guard for the saplings. For many others, including women, the plantation project is providing jobs and a sense of purpose.

Also Read: Snakebites kill more Indians than malaria, dengue. Blame the urban-rural divide

Villagers in charge

A muddy canal cuts through the harsh, sun-baked landscape of the island off Kudikadu, where about 20 villagers tend to small saplings along the slushy embankments. If all goes to plan, these thousands of saplings will grow into a lush mangrove forest, shielding the shoreline from angry floodwaters, nurturing a thriving underwater ecosystem, attracting birds, and providing livelihoods.

But the quest to restore mangroves in Cuddalore doesn’t stop here. Next on the agenda is Devanampattinam village, where Aruldoss’ department has identified 25 hectares for a new mangrove forest. Restoration efforts are also underway on 100 acres each in Killai and Kodiyampalayam, where existing mangrove forests are being revitalised.

For each of these projects, the government is banking on the help of local residents. Regional forest offices are now establishing Village Mangrove Councils (VMCs) in all districts where the initiative is being implemented. According to Srivastava, 17 such councils are being formed in various villages across Cuddalore, Thanjavur, and Thiruvarur districts.

“The purpose of the councils is that they give a sense of ownership to villagers. If they get involved in planting, they will also protect the mangrove,” he said.

Saving mangroves is a global priority. Often called ‘carbon sponges’, they absorb vast amounts of greenhouse gases and help mitigate climate change. Yet, worldwide efforts to protect these threatened ‘blue forests’ have often faltered, from the Sundarbans to Sri Lanka. And there’s consensus among experts that other than precise cultivation, involving local communities in conservation and making it worth their while is crucial.

In Cuddalore, the response has been encouraging from villagers, including those from tribal communities. Iqbal B, the Forest Range Officer in Cuddalore’s Pichavaram said the VMC he set up in Kalaignar Nagar, a village dominated by the Irula tribe, has 30 members, led by a fellow villager.

These VMC members are given jobs like planting, desilting, and patrolling, with men earning Rs 650 a day and women Rs 375. But the chance to supplement their income is not the only reason why they’re invested in the success of the project.

“Their lives are dependent on the mangroves for fishing and other activities,” Iqbal pointed out. “If this becomes a success, we will set up more such committees here.”

Presently, the department hires residents like Kudikadu’s Balaji as daily wage labourers in areas without established councils.

Earlier, we made only about Rs 500 from our catches. Now, it has increased to Rs 1,000

– Balaji, Kudikadu resident

Until he started working for the forest department, Balaji relied solely on fishing to make a living, earning about Rs 500 a day. Now, he makes Rs 800 as a guard for the saplings. For many others, including women, the plantation project is providing jobs and a sense of purpose.

“I have planted many saplings in Killai,” said 26-year-old Kalaignar Nagar resident Palaniyamma proudly. “I earn Rs 350 a day whenever I get work from the forest office.”

India’s first tidal nursery

A long-lost mangrove forest is slowly coming back to life deep in the Kallukuttai backwaters of Cuddalore’s Killai, about 32 kilometres from Kudikadu. Among the full-grown mangrove trees that cover about a third of the 100-acre land, saplings of Avicennia and Rhizophora are taking root in the bare, muddy patches.

To revive this ecosystem, 10,000 saplings have been planted, said Iqbal B. A blue cloth net canopies the entire area, shielding the young plants from roaming cattle. This restoration is a community effort, with residents from nearby hamlet Kalaignar Nagar stepping up to help. These villagers, mainly fisherfolk, are no strangers to growing the the saplings, Iqbal said. They also carry out desilting and maintenance tasks at the sites.

This area was once abundant with thillai trees, a local name for the mangrove species Excoecaria agallocha, but they nearly vanished after being heavily cut down for fuel. Now, alongside the Rhizophora and Avicennia, Iqbal is making sure thillai trees are part of the restoration plan.

Close to the forest, Iqbal and his team have established what they claim is India’s first tidal mangrove nursery, housing nearly 200,000 saplings. These plants, mostly Rhizophora and Avicennia, are at various stages of growth and will soon be planted in selected locations, including Kudikadu in Cuddalore.

Unlike the usual method of directly planting saplings in their final location, these plants undergo a special process. First, the propagules, or seeds, are collected from existing mangrove forests such as Pichavaram. They are then placed in polybags and grown in freshwater. After this, they are transferred to tidal water for a ‘hardening’ process that improves their chances of survival in the wild, Iqbal explained.

Once they are ready, these saplings will be planted not only in Kudikadu and Killai but will also be used to restore mangrove forests across the district.

The saplings have a long way to go but new dreams are taking shape in Kudikadu. They have a role model close by—the Pichavaram mangrove, which was designated as a Ramsar site in 2022 and is a popular destination for boating.

More fish, tourism hopes

The mangrove project hasn’t just helped Balaji through his guard duty wages. It also helped him make more money from fishing in the Uppanar’s waters.

“Earlier, we made only about Rs 500 from our catches. Now, it has increased to Rs 1,000,” he said.

The Uppanar River—where Kudikadu and nearby villages like Eechangadu, Karaikadu, Sothikuppam, and Rasapettai depend on fishing—is home to prawn, crab, catfish, and grey mullet.

Mangroves, which thrive in salty waters, improve water quality by filtering out nutrients. Fish often use the shallow waters beneath these trees as nurseries. Balaji said he noticed an increase in fish soon after the planting was done on the island.

While Balaji serves as the island’s guardian, nearly 15 labourers from Killai villages tend the saplings daily.

These workers are transported by tractor and accompanied by Aruldoss, who oversees the project on the ground. He said they have long relied on mangroves for their livelihood and so are familiar with the work and get it done efficiently.

“Desilting is done almost every day. We also replace saplings that show signs of decay,” Aruldoss said, adding that almost all the saplings are thriving on the island.

The project is now attracting interest from local NGOs, Aruldoss added. Some have approached his office, seeking permission to expand mangrove planting around the island, and officials are considering the proposals.

The saplings have a long way to go but new dreams are taking shape in Kudikadu. They have a role model close by—the Pichavaram mangrove, also in Cuddalore, which was designated as a Ramsar site, a wetland of international importance, by the Narendra Modi government in 2022. It’s the second-largest mangrove in India and a popular tourist destination, especially for boating under the mangrove canopies.

“Once grown, the Kudikadu island could become another Pichavaram with tourism potential,” Aruldoss said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)