New Delhi: A professor at TISS Guwahati has started to think twice before speaking in class. He’s wary of students making videos and then misrepresenting what was said.

“There’s a fear that students might be recording us, and whatever we say could be taken out of context and posted outside. I do not feel safe in my own class,” the professor, who has been with TISS for five years, said on condition of anonymity. Independence of thought and the right to speak freely are now slipping out of reach, according to him.

A quick succession of events has cast a shadow of unease over the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, from a Dalit student being suspended for alleged ‘anti-national activities’ last year to nine students now facing criminal conspiracy charges for holding an event in October for the death anniversary of human rights activist GN Saibaba. Student groups have issued statements warning of attempts to promote “repression and surveillance”. Others have protested new admission rules based solely on standardised scores, saying the move aligns with a “saffronisation” agenda.

These incidents took place in Mumbai but are reverberating in the Guwahati and Hyderabad campuses as well.

Change is afoot at TISS, the oldest school of social work in India. Its governance moved from the Tata Trusts to central government control in 2023, and it’s shaking the very foundation of the institute. Polarised, ideologically charged central university student politics have entered campuses that were once hubs of anti-establishment activism, from anti-CAA protests to caste justice.

As a deemed university receiving over 50 per cent of its funding from the central government, TISS was brought under the Ministry of Education’s administrative purview after new UGC rules came into force in 2023. This effectively ended the Tata Trusts’ primary authority in key appointments and replaced the Tata-led governing board with a government-appointed executive council.

Now, instead of taking on systemic injustices together, students are looking at each other with suspicion.

Physical scuffles on campus have become a regular occurrence, students said. A fear psychosis is taking over. WhatsApp groups are erupting into ideological fights, and film screenings are dividing students. Teachers are debating whether to ban phones in class. Police are scanning the campus, and classrooms are teeming with ‘spies’. The institute is churning through an uneasy evolution, and many fear it will lose its ethos in the interim.

“TISS is perhaps expanding without understanding how to sustain itself in the long term. It needs to regain its voice. We need to be enabled to do what we were doing earlier, and navigate the transition to a central university in a more lucid manner. Otherwise, our credibility will take a beating,” a former professor of TISS Mumbai said.

ThePrint interviewed seven teachers across TISS Mumbai, Hyderabad, and Guwahati, and six students. All requested anonymity over fear of retribution.

The administration, however, vehemently denied any police presence or climate of fear on campus.

“Police comes only if there’s an incident on campus,” said an administrator at TISS Mumbai on condition of anonymity, adding that allegations of fights among students and paranoia among teachers are “completely baseless”.

Also Read: The silent crisis at Delhi’s CSDS. A fund freeze after show-cause notice

Is ‘pro-poor’ ethos under threat?

For decades, the leafy, red-brick TISS campus in Mumbai’s Deonar prioritised access for students from marginalised backgrounds. Among India’s oldest and best-known centres for social work and advanced social science research, “diversity and inclusion” were held up as pillars, kept standing not just through quotas, but through fee concessions, scholarships, and dedicated offices such as the Equal Opportunity Centre (EOC) and the Social Protection Office (SPO).

Critics now say those pillars are beginning to crumble.

Earlier, admission to TISS was done via TISSNET, which included a paper, group discussions, and an interview. But with the introduction of the Centralised University Entrance Test (CUET), the institute has less control over admissions. Starting from the 2025-26 academic session, admission interviews were scrapped, leading to an outcry that relying on an “objective” metric based on MCQs would disadvantage students from Dalit, Adivasi, and other disadvantaged backgrounds.

We knew exactly what kind of students were coming to our institute earlier; now we have lost that ability to screen students, maza nahi aa raha (the spark is gone). Engineering students or students with access to coaching will definitely perform better at MCQ kind of questions.

-TISS Mumbai teacher

“Online assessment, especially interview in TISS admission process, always helped students from varied social backgrounds, including those from vernacular mediums, those without access to coaching, and those who express their thoughts through subjective understanding rather than objective answering skills,” said a joint statement by the Adivasi Students’ Forum (ASF), Ambedkarite Students Association (ASA), Fraternity, North East Students Forum (NESF) and Progressive Students Forum (PSF). Some teachers agree with them.

“We knew exactly what kind of students were coming to our institute earlier; now we have lost that ability to screen students, maza nahi aa raha (the spark is gone),” one MA teacher at TISS Mumbai said. “Engineering students or students with access to coaching will definitely perform better at MCQ kind of questions.”

🚀 Ready to take your education to the next level? Apply for a Postgraduate degree at TISS!

📅 Applications open: 14 Dec 2025

⏳ Last date: 14 Jan 2026

Apply for CUET-PG here: https://t.co/y5v9Fjda4g

Check out the full update: https://t.co/n83HiyYRIk pic.twitter.com/TWYc0OsqNJ

— TISS – Tata Institute of Social Sciences (@TISSpeak) December 19, 2025

Now, say some teachers and students, self-funded seats are on the rise on campus and there’s a growing skew toward students from certain states.

“The campus is much more North Indian than ever before. Students from UP-Bihar dominate new admissions,” a PhD student at TISS, who also belongs to UP, told ThePrint.

However, Dr Sunil D Santha, the dean of academic affairs at TISS Mumbai, maintains that the CUET has helped the institute get and even more diverse set of students.

“Next year we’re planning to increase our reach to rural centres of the country, not just urban centres,” he said.

The raison d’être of TISS was to professionalise social work in India, and produce experts equipped to tackle the country’s challenges in development, policy-making, and social justice.

Set up in 1936 by the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, TISS had the American missionary and sociologist Dr Clifford Manshardt as its first director. The idea was to create a framework for trained professionals to take on the country’s vast social, economic, and industrial problems, including poverty and labour welfare, rather than rely solely on charity or voluntary efforts. The Mumbai campus was inaugurated in 1954 by then PM Jawaharlal Nehru.

Since its inception, TISS has played a leading role in shaping India’s welfare policies, labour laws, and public administration reform. Its early efforts included a Child Guidance Clinic, now the Muskaan Centre for Child and Adolescent Guidance, and post-Partition relief work, which began a tradition of sending teams into disaster-struck areas.

Recognised as a Deemed University by the Government of India in 1964, it has produced some of India’s most notable voices in activism and social entrepreneurship. Medha Patkar, best known as the face of the Narmada Bachao Andolan, reproductive and sexual health expert Purnima Mane, billionaire and philanthropist Anu Aga, and Raju Kendre, founder of the education-focused Eklavya Foundation, are all alumni.

Over the years, TISS expanded its horizons, steered by S Parasuraman as the director from 2004-18. Its interdisciplinary academic programmes increased from four to 50, and the institute opened new off-campus sites in Hyderabad and Guwahati. Parasuraman reportedly declared that he was “pro-people and pro-poor”— language that even trickled into the 2018-2021 prospectus.

Not all teachers are singing a dirge to this ethos. Some are even hopeful it will get a leg up with CUET. They argue that it actually expands the scope of students coming from different geographies.

“TISS has always had first-generation learners, students from marginalised backgrounds coming here. I don’t think that can change,” a teacher said.

The institute’s new vice chancellor, Badri Narayan, also insisted that the change was forward-looking.

“Our diversity is intact. TISS is a world-level institute of research, and we have a socially embedded pedagogy of teaching people. Classrooms have to evolve,” he said.

But the campus culture of TISS, too, is transforming and becoming increasingly polarised.

‘Spies’ on campus

A student of Media and Cultural Studies at TISS was quietly writing her semester examination in October 2025 when a knock on the door interrupted her. Police officers were waiting outside. She answered their questions and returned to her paper like it was nothing.

Dealing with the police and talking to lawyers has become commonplace for her. She is one of nine students facing ‘criminal conspiracy’ charges filed by the Trombay Police.

It is students who take photos of women smoking, professors smoking, taking stock of who they talk to, and what they talk about. I have myself deleted such photos from students’ phones

-PhD student

The case stems from a memorial event the students hosted on 12 October 2025 for GN Saibaba, the late former Delhi University professor and activist who was acquitted by the Bombay High Court in March 2024 in an alleged Maoist links case under UAPA. An assistant professor is known to have filed the complaint.

“We didn’t shout any slogans. It was just a memorial, in solidarity, quietly,” the student told ThePrint in New Delhi.

This event was a turning point for the TISS campus. Since then, students claim, free speech has been stifled. WhatsApp groups where students once engaged in impassioned debate have gone quiet, and there is a pervasive fear that police in plainclothes are listening to every conversation and watching every step.

There is fear that students are telling on teachers to the police. All six students, one alumna and three teachers alleged that student ‘spies’ were reporting back to the nearest BJP office or RSS shakha.

“It is students who take photos of women smoking, professors smoking, taking stock of who they talk to, and what they talk about. I have myself deleted such photos from students’ phones,” the PhD student quoted earlier said.

Teachers are purportedly not in the clear, either.

“Teachers have had to stop students from recording them. Some of them have also debated not bringing phones to class for the same reason,” a student said.

In the last decade, the BJP, often through its student wing, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), has been actively attempting to make inroads into traditionally Left-leaning and critical academic spaces such as JNU—a project that, as reported earlier by ThePrint, seems geared to “dismantle their cultural and intellectual dominance in the country”.

In TISS, too, Left versus BJP friction has been brewing for a while. In February 2018, for instance, students raised political slogans while protesting against the cancellation of a hostel and dining fee waiver for students from marginalised communities— such as “BJP humse darti hai, TISS ke funds cut karti hai” (‘BJP is scared of us, it cuts TISS funds’), and ‘Yeh sarkar nahi chalegi’ (this government will not do).

But over the last couple of years, the conflict has escalated.

An ideological battleground

In January 2023, more than 200 students at TISS Mumbai streamed a banned BBC documentary on Prime Minister Narendra Modi despite an administration warning and a BJP Yuva Morcha protest outside the campus. The Progressive Students’ Forum later said, “TISS admin denied one screen, students arranged ten.”

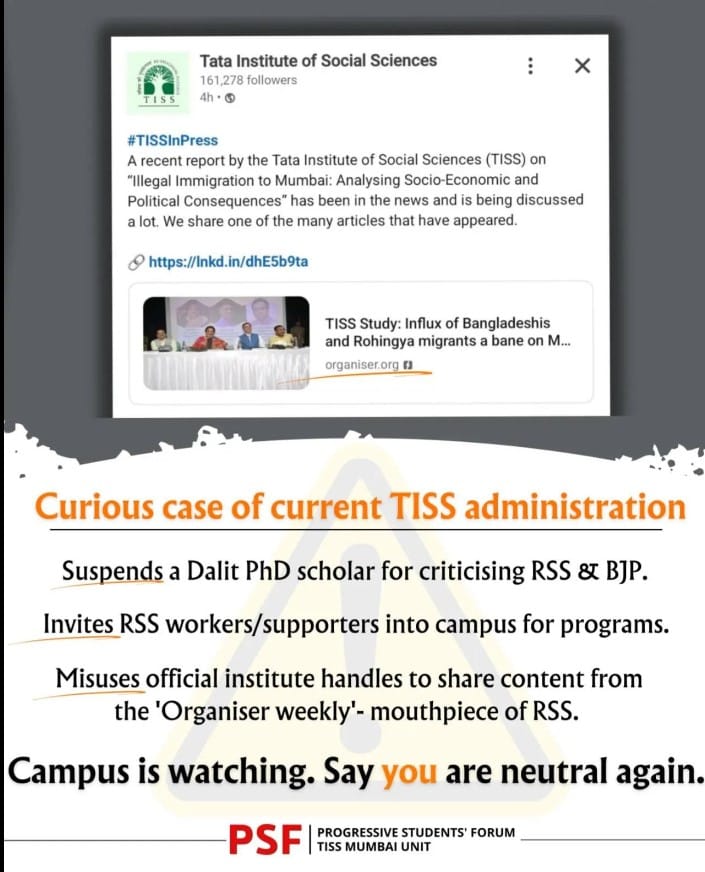

A year later, the consequences of dissent were more severe. In April 2024, a Dalit PhD scholar, Ramadas Prini Sivanandan, was suspended for two years over alleged “anti-national activities”, including participating in protests against government policies like the National Education Policy (NEP) and screening the documentary Ram ke Naam, which is searingly critical of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement.

The suspension became a major point of political contention on campus, with more than 350 people from 16 human rights groups staging a protest near the campus this year, demanding his immediate reinstatement. The Bombay High Court dismissed Sivanandan’s petition, but in May, the Supreme Court reduced his suspension to time already served.

ABVP leaders are now openly declaring TISS as a target institution, claiming a need to counter “anti-national” and “Leftist” activities and instil a sense of nationalism, according to the students and teachers who spoke to ThePrint.

Left-leaning students are regularly accused of being ‘urban Naxals’. The encounter death of Naxal leader Madvi Hidma in November was framed by some students as a cautionary tale on a WhatsApp group called ‘TISS for Everyone’.

“A massive expose on how urban naxals are created and planted in metros! Reality of many protesters and Maoist-sympathizing events on campus?” said one message.

A response from the other side of the ideological divide read: “Classic Nazi/fascist toolkit lmao.”

The institute in totality is promoting the agenda of the Hindu right, deviating from the legacy of TISS

-TISS student

Meanwhile, Right-wing students have been screening controversial films such as Demography is Destiny, about the increasing Muslim population in Mumbai, and The Kerala Files. No action was taken against such screenings.

“The institute in totality is promoting the agenda of the Hindu right, deviating from the legacy of TISS,” one student said.

Teachers are afraid that a new aggressive student politics is gaining ground in TISS, even as traditional protests and debates get suppressed.

An alumna of TISS, now a writer in New Delhi, said the institute never had rowdy politics, but chaupal-style discussions were common when she was on campus between 2019-2021.

“Students used to have heated debates about things like CAA, NRC right on the campus. They were civil even if heated. There was space for students to debate and discuss,” the alumna said.

She added that protests at TISS usually required permission, but during NRC agitation in 2021, some students took photos of protesters and sent them to the local police station, after which multiple students were detained.

“That is when things started going bad,” she said.

Also Read: Built to fix cities, billionaire-funded, 16-yr vanvas—story of Bengaluru’s IIHS University

Surviving the turbulence

A big jolt came in June 2024 when 100 teaching and non-teaching staff were abruptly served termination notices due to the “non-receipt” of funds from the Tata Education Trust.

Within two days, the termination notices were withdrawn and assurances from then interim head Manoj Kumar Tiwari communicated to staff. But the incident left a sense of foreboding in its wake.

“We felt a kind of a black cloud over our heads last year. It almost felt ominous for what was supposed to come,” a faculty member said.

The tremors had been building since September 2023 when the government-appointed Executive Council replaced the Tata-led Governing Board, and the post of director was formalised into a Vice-Chancellor, bringing TISS firmly under the purview of the Ministry of Education. The official catalyst for the change in leadership structure was the completion of the five-year term of the previous full-time head, Professor Shalini Bharat.

In this churn, Manoj Kumar Tiwari, who is also director of IIM-Mumbai, was appointed as interim head. His arrival, for some teachers, signalled a culture clash between ‘managerial’ logic and the activist soul of TISS.

We teach a unique kind of social science, where management is part of our courses, but it is based on socially rooted knowledge. We just don’t teach management skills; we teach how to manage things in society. Our placement is 79 per cent; we want to take it to 100 per cent

-Badri Narayan, VC of TISS Mumbai

Under Tiwari, the campus saw what one professor called the “engineerisation of social sciences”. In order to climb the NIRF (National Institutional Ranking Framework) rankings, there were rumblings that the administration had begun prioritising metrics over mission.

“Humanities cannot come with a fixed matrix. Patents are common in tech, but now at TISS, we have been running to get patents for extra weightage. This is uncommon,” said a professor.

Management-focused courses started gaining precedence, claimed some teachers, and there was more red tape involved in organising guest lectures.

“When we didn’t have a permanent VC, the red tape was bad. Things didn’t move fast. There was oversight on who to call and who to not call. Conferences had dipped, the college wasn’t open to dialogue,” a professor said.

However, other professors argued that though TISS went through a period of flux, there wasn’t necessarily a ‘management turn’ under Tiwari. They pointed out that placements have always mattered at TISS, describing it as an interdisciplinary institute focused on social work rather than conventional academic social sciences.

Santha said the four management courses—master’s in Human Resources Management and Labour Relations; Organisation Development, Change and Leadership; Hospital Administration; and Social Entrepreneurship—see 100 per cent placement. In social science courses, he added, placements hover between 81 and 85 per cent.

“We teach a unique kind of social science, where management is part of our courses, but it is based on socially rooted knowledge. We just don’t teach management skills; we teach how to manage things in society. Our placement is 79 per cent; we want to take it to 100 per cent,” said sociologist Badri Narayan, who was appointed as the VC of TISS in July 2025.

With Narayan taking the reins, there is a cautious optimism that the institute can bridge the gap between its ‘pro-poor’ foundations and its changing identity as it approaches its 90th year.

“The hope is that with the new VC, things will change,” a professor said.

Narayan has a grand vision for what he calls the ‘neeyati’ (destiny) of TISS.

“We are having constant discussions in classes and evolving a social change model. We will implement these models on the field and take these models to villages,” Narayan said.

The branches in Guwahati and Hyderabad, he added, will be turned into research consortiums so they can become the premier institutes of their own regions. Legacy will not be neglected either, according to him, with two books in the works on the history of TISS as the pioneer of social work.

“If we lose TISS, we will lose national assets,” a teacher in the Mumbai campus said. “Negativity doesn’t give anything to our institutes. We need to save them.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

What rubbish!!!! I am a TISS grad. I am anything but a “radicalized” person. I went on to get my PhD in business from an ivey league–TISS is a key factor in my success. It encouraged me to think, to lead not just to follow.

I was at TISS recently. It was heart breaking to speak with students. No hostels. no discussions and a steep decline in intellectual discussion. And, yes, these were intellectual discussions. Some did talk about Marxism and while others criticized it. We discussed issues without judgment. That was the beauty of TISS.

I know for a fact that some of the leftists professors at TISS have contacts in the Army, they knew about the hot pursuit in Myanmar and have details about it from top sources.

TISS is mostly a facade used to control opposition to the government, the leftists there are left wing in name only, please don’t be deceived, they aren’t urban naxals, they are merely pretending to be.

Again as much as I hate these urban naxals you can’t suppress their speech. Speech is the only way to solve conflicts. The left is facing what the right faced for decades and now they are pissed off.

Why did the left not advocate for free speech for the right ? Do they ? Anyway I want free speech for everyone in my country.

It’s a well known fact that such universities are a breeding ground for radicalization. I mean we are already facing these woke idiots even though we are not a wealthy nation.

“Open debate” – really ? You think citizens are stupid ? It’s just leftist who control everything in these spaces. So much for “democracy”