Patna: In Bihar’s politics of social justice, it isn’t always easy for upper castes to speak up about their rights. But when the state’s Savarna Ayog members recently went to conduct a discussion in Muzaffarpur, they were surprised by how impatient people were.

One villager asked them a provocative question.

“Instead of just coming for a meeting to discuss and observe the situation, why don’t you focus on making welfare schemes for upper castes?” Vinod Mishra asked the Ayog, also known as the Bihar State Commission for Development of Upper Castes. “The caste survey has already bared the ground reality, it’s time for action.”

The team of the Savarna Ayog, a body set up in 2011 to look into the plight and rights of Bihar’s 15.5 per cent upper-caste population, was pleasantly surprised. Mishra’s appeal at the collectorate auditorium gave voice to the urgency on the ground among Savarna groups. That growing clamour has come as a relief to the Ayog’s members as various caste groups lobby and mobilise ahead of the ambitious all-India caste census, due to start in the coming April. Chief Minister Nitish Kumar used the opportunity to revive the moribund Ayog in May 2025, months ahead of the state elections.

In the post-Mandal Commission era of OBC-dominant politics, Savarnas, or upper-caste groups, in Bihar have been reeling under an unbearable heaviness of being left behind by history. The Ayog now wants to address this grievance of historically privileged groups by identifying deprived and underprivileged families among the upper castes.

In its second coming, the Savarna Ayog has been busier than Bihar’s commissions for backward classes and minorities. Its office in Patna has been abuzz. A flurry of petitions from upper castes across the state is flooding its desks; members hold meetings to instruct district IAS officers to pay extra attention to upper castes, and listen to the community’s problems in village sabhas.

Since independence, no leadership has considered the upper-caste community. Nitish Kumar has clarity that poverty exists even among Savarnas and that their inclusive development is a must

MP Singh, president of the Bihar Savarna Ayog

“The upper castes are going through a very difficult phase today. The land they own has been fragmented, and ownership has been shifted to backward communities. It has created economic hardship. Now the onus is on the Ayog to examine this and recommend some affirmative actions for Savarnas,” said Mahachandra Prasad Singh, president of the Savarna Ayog and a senior BJP leader.

Singh said the Bihar caste survey revealed that 9.98 per cent of the Hindu upper-caste population has migrated out of the state, a far higher proportion than OBCs and EBCs.

“Since independence, no leadership has considered the upper-caste community. Nitish Kumar has clarity that poverty exists even among Savarnas and that their inclusive development is a must,” he added.

While the Nitish Kumar government projects the Ayog as evidence of its concern for economically weaker Savarna groups, critics and beneficiaries alike say it risks joining Bihar’s long list of high-profile commissions whose recommendations gather dust. They hark back to examples such as the Bandyopadhyay Commission on land reforms and the Muchkund Dubey Commission on education reforms.

“In Bihar, the Nitish Kumar government has formed several commissions, but it has consistently avoided implementing their recommendations. Commissions are often created simply to send a message to a community, creating the impression that the government is working on its behalf,” said DM Diwakar, economist and former director of Patna-based AN Sinha Institute of Social Sciences.

In the last eight months, the Ayog has also faced criticism from opposition parties. On January 20, MP Chandrashekhar Azad’s Aazad Samaj Party (Kanshi Ram), called the commission ‘Manuvadi’.

“The government’s job is to abolish the caste system, not to give it official certification as ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ castes. When the state itself declares a caste as ‘upper’, it institutionalises inequality, not equality,” posted the party’s official handle on X.

“उच्च जातियों के विकास के लिए राज्य आयोग” बनाकर एनडीए सरकार ने यह साफ कर दिया है कि वह संविधान नहीं, बल्कि ऊँच-नीच की मनुवादी सोच से शासन चला रही है।

सरकार का काम जाति व्यवस्था को खत्म करना होता है, न कि उसे ‘उच्च’ और ‘निम्न’ का सरकारी प्रमाण-पत्र देना।

जब राज्य खुद किसी जाति… pic.twitter.com/w3FH4zk9d8

— Aazad Samaj Party – Kanshi Ram (@AzadSamajParty) January 20, 2026

Diwakar said there is little doubt that educational and economic backwardness exists among upper castes in Bihar. Most parties need the votes of upper castes, he added, questioning whether there was real political will behind the Ayog.

“The harsh reality is, if there is a will, there is a way. If there is no will, there is a committee in Bihar,” he said.

Also read: Bihar Bhumihars ask ‘Who are we?’ Brahmin or OBC, zamindar or oppressed

New energy, growing impatience

Days after the Savarna Ayog was revived, Bhumihar leader Ashutosh Kumar announced the Samanya Warg Adhikar Yatra, a campaign for the rights of general-category youth in Bihar.

Kumar’s slogan was ‘Savarna yuvaon lalkar do, Sarkar se kaho adhikar do’—Upper-caste youth, shout out loud, tell the government to give us our rights.

The launch of the Savarna Ayog 2.0 has sent a ripple of energy through upper-caste groups and given them a new platform for mobilisation.

“After Mandal politics, the upper caste took the back seat in Bihar. They not only lost their dominance, but faced economic hardship. Amid 35 years of darkness, the Savarna Ayog is a ray of hope for upper castes in Bihar,” said 22-year-old Avnish Mishra, a resident of Begusarai.

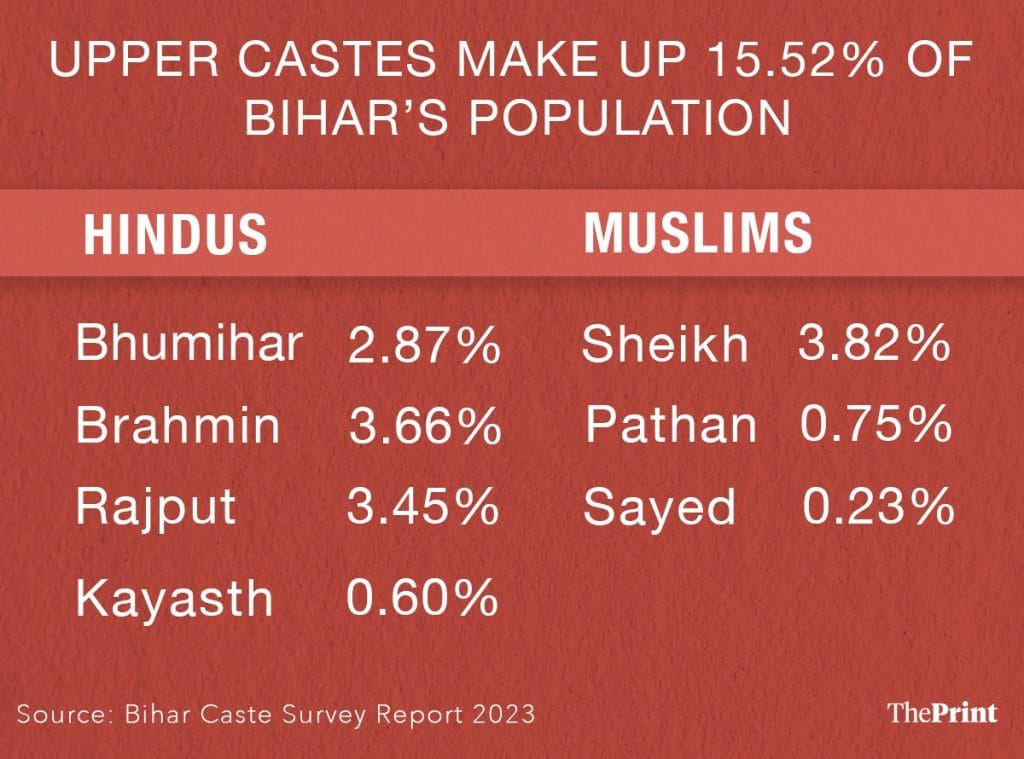

Bihar’s 2023 caste survey shows that of the state’s 15.5 per cent upper-caste population, Brahmins make up 3.65 per cent, Rajputs 3.45 per cent, Bhumihars 2.87 per cent, and Kayasthas 0.60 per cent.

Mishra is now impatiently waiting for the government to make specific schemes for Savarnas in the economically weaker section (EWS) category. The graduate of Patna University applied for an EWS certificate last year to be eligible for the UPSC reservation but it’s yet to come through.

“Last year when the Ayog was announced, we were hoping that it would be a changemaker. But months have passed, it is still in meeting mode. Nothing concrete is happening on the ground,” said Mishra.

However, the Ayog has started a process of aggressive outreach and has ramped it up in recent weeks.

Savarna Ayog on ground

In the second week of January, a Savarna delegation from Nalanda arrived at Ayog president MP Singh’s residence in Patna’s Vidhayak Colony.

The BJP leader, elegantly dressed in a starched white dhoti, played the host with practiced humility, serving sweets before settling in to listen. The table at his home office is buried under a mountain of bouquets from visiting delegations.

Over the past few months, this house has morphed into the nerve centre for upper-caste advocacy.

“People have high hopes from the Ayog. They keep coming to discuss the problems faced by upper-caste communities. They see hope in me and, as president, I have a very big responsibility to address their concerns,” said Singh.

For nearly half an hour, Singh walked the Nalanda delegation through the Ayog’s work and took questions from them. One member flagged difficulties in securing EWS certificates.

“Despite coming from the economically weaker section, our children are not eligible for EWS. Shrimaan ispar jald karyavahi kijiye, ye hamare bachho ke bhavishya ka saval hai (Sir, please take immediate action; this concerns our children’s future),” he said.

Acknowledging that this was a common concern across the state, Singh presented the group with reassuring data. He cited Muzaffarpur, where between 2025 and 2026, 6,270 EWS applications were submitted and 6,222 cleared.

“We instructed district officials to check the basis for 48 rejections and to send a report to the Ayog,” he said, adding that the commission was tracking each application.

After Mandal politics, the upper caste took the back seat in Bihar. They not only lost their dominance, but faced economic hardship. Amid 35 years of darkness, the Savarna Ayog is a ray of hope for upper castes in Bihar

-Avnish Mishra, a resident of Begusarai

The Ayog has also sought to project vigilance beyond welfare issues. On 11 January, a girl preparing for NEET died a few days after being found unresponsive in a Patna hostel. While the case was initially termed a suicide, her family alleged sexual assault and murder, triggering protests across the city. A Special Investigation Team was formed and the hostel sealed on 20 January.

“There can be no compromise on the safety of our daughters in a civilised society. The truth behind her death must come out, and the culprits must be punished within a stipulated time frame,” said Singh, who visited Jehanabad to meet the victim’s family on 22 January. In a Facebook Live, he could be seen holding court in front of a large gathering of villagers.

It has been a relentless eight months for Singh since the Ayog swung into action at its Nehru Path office last May. In its first meeting in June 2025, it formed three sub-committees to examine proposals such as free coaching, hostels for poor students, and age relaxation in government jobs for Savarnas. It has since held more than a dozen meetings across seven administrative divisions: Patna, Magadh, Munger, Tirhut, Saran, Darbhanga, and Kosi.

With a three-year tenure for all members, the clock is ticking. Initially, the Ayog planned to visit all the 38 districts, but switched to a division-wise strategy to save time ahead of elections. Each day-long meeting has three phases: discussions with officials, suggestions from prominent members of society, and a media interaction.

New demands come up in almost every meeting. In Muzaffarpur, Keshav alias Mintu, secretary of the Rashtriya Bhumihar Brahmin Parishad, submitted a five-point memorandum, including a call to reinstate “Bhumihar Brahmin” as a category in official caste listings.

“In the coming days, we will cover Purnea and Bhagalpur. After that, we will prepare a concrete report with recommendations,” Singh said.

Who is in the Savarna Ayog?

MP Singh’s residence is a personal museum of his ideological lineage. Portraits of Bhumihar revolutionary Sahajanand Saraswati and Bihar’s first chief minister, Shri Krishna Singh, hang on the walls. His office houses an extensive collection of books, including his own works on Sahajanand Saraswati, Jyoti Kalash and Amrit Kalash.

A prominent Bhumihar leader, he is a former minister and six-time MLC. Earlier associated with Jitan Ram Manjhi’s Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular), he left the party in 2019 to form HUM United before later joining the BJP.

He is not the only heavyweight on the five-member panel, which also includes another BJP leader, a former RSS pracharak, and a JD(U) spokesperson.

Political reach is part of the equation. When Ayog member and BJP leader Rajkumar Singh visited his hometown of Bhagalpur last June, he was met with shawls and bouquets at Zero Mile Chowk. His first stop was symbolic: garlanding the statue of Rajput icon Babu Veer Kunwar Singh, a key organiser of the 1857 rebellion from Bihar’s Bhojpur region.

“The BJP government is working for all sections of society. The interests of the upper castes will not be ignored. We will place the community’s concerns before the government through the commission,” he said at the event. Before joining the BJP in 2017, he was with the JD(U) and has been the party’s Banka district in-charge since 2023.

The government is preparing targeted welfare schemes, including hostels for boys and girls in all districts, to promote education among children from economically weaker upper-caste families

-Jai Krishna Jha, Savarna Ayog member

Unlike the 2011 panel, the Ayog’s composition is strictly Hindu, with members from the Bhumihar, Kayasth, Brahmin, and Rajput communities. Upper-caste Muslims—such as Syeds, Sheikhs, and Pathans—who constitute about 4.8 per cent of Bihar’s population, have no representation on the panel.

Vice-president Rajeev Ranjan Prasad, a Kayasth leader, is also the national spokesperson for the JD(U) and frequently appears on television defending the party.

The Brahmin contingent comprises senior JD(U) leader Dayanand Rai and BJP’s Jai Krishna Jha.

A businessman from Darbhanga, Rai is a close aide to JD(U) president Sanjay Jha. Ahead of the 2020 Delhi Assembly elections, he was appointed JD(U)’s Delhi unit president, with the party contesting two seats.

Jai Krishna Jha, a former RSS vibhag pracharak from Samastipur, describes himself as a reformer, political analyst, and nationalist on his social handles. In May 2025, he received the Champions of Change Award from Bihar governor Arif Mohammad Khan for his work in education and social welfare, particularly for underprivileged girls.

Citing Bihar government data, Jha said nearly 49 per cent of the upper castes in the state live below the poverty line.

“The government is preparing targeted welfare schemes, including hostels for boys and girls in all districts, to promote education among children from economically weaker upper-caste families,” he added.

Also Read: Are Delhi private schools failing the EWS test? 15 yrs of silent segregation, NGOs filling gaps

The slow fade of Savarna Ayog 1.0

This isn’t the first time that Bihar has tried to salve the grievances of the ‘deprived’ upper castes. In 2011, a year after a thumping Assembly election win, CM Nitish Kumar announced a commission for upper castes, colloquially known as the Savarna Ayog.

“The politics of Mandal-vaad created social alienation among a large section of the upper castes. Nitish Kumar worked to bridge this gap. What Modi did in 2019 with the EWS quota for Savarnas, Nitish had already done eight years earlier,” said Neeraj Kumar, MLC and spokesperson of the JD(U).

This first commission was headed by retired Allahabad High Court judge DK Trivedi, with the other four members being Krishna Prasad Singh, Narendra Prasad Singh, Farhat Abbas, and Sanjay Mayukh (later replaced by Ripudaman Srivastava).

However, progress was slow. So much so that in 2014, then Bihar CM Jitan Ram Manjhi proclaimed his displeasure on a speakerphone call to the principal secretary of the General Administration Department in front of mediapersons.

“They have spent over Rs 15 crore so far but have not written even a line of report,” he said.

I recommended that the upper caste only needs educational and economic upliftment. They are already socially uplifted

-DM Diwakar, economist

It took another year for the report to finally arrive. Titled Survey of Economic and Educational Status of Upper Caste Population in Bihar, it was compiled with the help of the Patna-based Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI).

The 2015 report noted that despite higher average incomes, many upper caste households lived below the poverty line. The poverty ratio for upper-caste Hindus stood at 10.3 per cent in rural areas and 5.4 per cent in urban areas. Among upper-caste Muslims, it was 10.7 per cent and 10.4 per cent respectively.

“The state government also needs to undertake some specific steps to help the upper caste population,” recommended the report. The data entered the political discourse, including a 2015 internal party article by senior JD(U) leader K C Tyagi titled Savarno mein bhi pichdapan (Backwardness also amongst upper castes).

“Due to the lack of job opportunities, many upper-caste families are facing financial hardship,” he wrote.

However, momentum fizzled out, and the report’s prescriptions went mostly unheeded. It proposed treating Savarnas earning up to Rs 1.5 lakh a year as poor, even though Bihar had no similar income cut-off for other groups then. The state later began using Rs 72,000 a year as its poverty benchmark after the caste survey. The commission also asked for welfare coverage and scholarships for upper-caste students below the poverty line. Nitish Kumar’s government implemented only one measure: a Rs 10,000 incentive for Savarna students who cleared Class 10 with first division.

Savarna demands have now ramped up, including reserved seats for EWS students in Kendriya Vidyalayas and Navodaya Vidyalayas, a higher age cap for EWS applicants in state competitive exams, and changes to the validity and land criteria for EWS certificates.

Economist DM Diwakar, who attended the commission’s initial meetings as an expert, said his recommendations were selective in scope.

“I recommended that the upper caste only needs educational and economic upliftment. They are already socially uplifted,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)