Lucknow/Mumbai/Pune: For VIPs coming to the City of Nawabs, all roads once led to the 180-acre fortified Sahara estate. That was some 15 years ago. Today, a white shirt is hung out to dry on its arched gate, locked and sealed with wax.

A notice from the Lucknow Municipal Corporation now claims what remains of the deserted estate, once the nerve centre of an empire with more than 36,000 acres in land assets and home to the first family of the Sahara Pariwar.

“Those were the times,” said a roadside vendor who had watched its zenith and decline. The riches that supposedly lay inside are still discussed, including apparently a surfeit of poultry. “Panch sau se zyada toh sirf Kadaknath murge the andar”— They bred over 500 Kadaknath chickens inside.

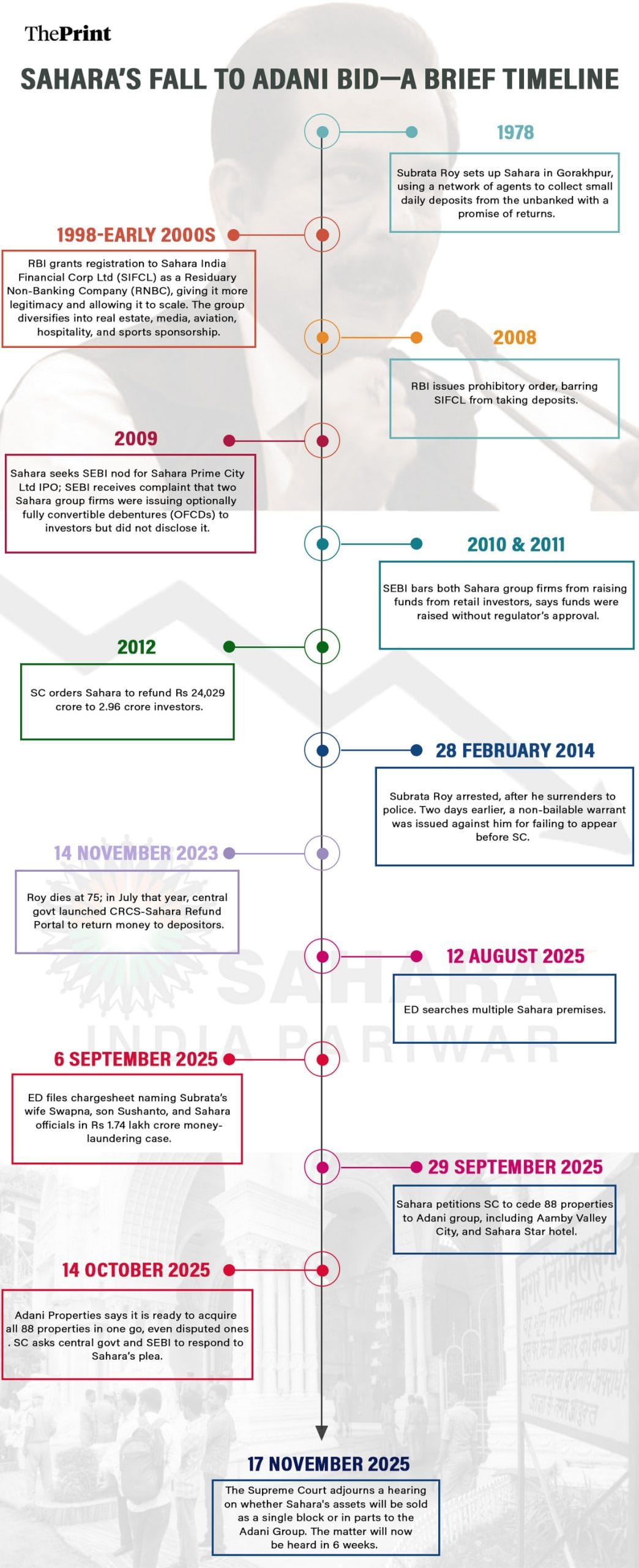

Sahara Shahar is one of over 80 parcels of land now on the block, to be ceded to the Adani group. If the distress sale goes through, the proceeds are expected to go toward refunding lakhs of Sahara depositors. The billion-dollar acquisition — bigger than any recorded in Independent India — will put the Adani group in a league few outside the old ‘Bombay Club’ have entered. It will also mark the sun setting on an empire born in the dusty bylanes of Gorakhpur in 1978.

Sahara’s founder Subrata Roy knew his skills were best put to use not in selling table fans or savoury snacks, but dreams in all shapes and forms—whether to the rickshaw-puller shut out of the banking system, or to the landed rich who longed for a slice of home in the Sahyadri Hills. Roy drew legitimacy from the holy trifecta of Indian public life: politics, cricket, and glamour. Like the Adani Group, his empire expanded at breakneck speed, its fingers in every pie, from real estate to finance, retail, hospitality, and sports. Both driven by an audacity to dream that stunned India.

For the Adani group, valued at Rs 2.88 lakh crore (over US$ 32 billion), the distress sale will bring bragging rights for two of Sahara’s crown jewels — the 10,000-acre Aamby Valley City near Pune and the Sahara Star hotel in the heart of Mumbai.

“They (Adani group) have the money, they will develop it,” said a Sahara kartavyayogi (employee) of 20 years.

Thousands like him were spectators to the multi-decade SEBI-Sahara battle that put ‘Saharashri’ Roy’s enterprise, worth at least Rs 1.6 lakh crore (around $18 billion) through the wringer.

The matter of the sale to Adani is now in the Supreme Court, where a bench headed by Chief Justice of India BR Gavai on 17 November adjourned the case for six weeks after the Centre asked for more time to respond. The amicus curiae in the case said in a 65-page report submitted to the top court Monday that more than 60 properties on the block have been attached by the IT department and other government agencies.

ThePrint e-mailed a questionnaire to the Adani Group as well as Sahara but hasn’t received a response.

Veteran journalist and political analyst Sharat Pradhan, who has long covered the Sahara saga, told ThePrint that Roy was “playing fraud” on poor people.

“He made all of his money from chit funds. That money was never returned to the poor people, though the high and mighty got their returns. He continued to pump money into the magical chit fund. You show dreams to innocent people who have no mechanism to understand it,” Pradhan said.

He added that if the distress sale goes through the “first thing” the Adani group should do is promise to pay salaries owed to Sahara employees.

“Adani inherited all the assets, he should inherit liabilities too.”

Also Read: Akhlaq lynching has changed everything in his village—politics to playgrounds

Diamonds to dust

As late as January 2013, Roy was still hopeful he could pull off a second time what no Indian going concern had done before.

“We have to expand. I want to see my 10 million people living happily. We did one announcement in the company and everyone’s remuneration went up by 50 per cent. I want to do that again,” Roy told journalist Tamal Bandyopadhyay, who recorded it in his book Sahara: The Untold Story. The reference was to 2002, when Sahara marked its silver jubilee with a 25-50 per cent hike in gross salaries for all employees and agents.

About a decade after this, Sahara’s fortunes began to plummet decisively. The Supreme Court intensified its scrutiny of the group’s fund-raising practices as SEBI moved to attach its properties over unpaid investor dues. At a November 2013 press conference, Subrata Roy called SEBI “vengeful” and a “sarkari goonda”. Sahara started refunding investors but could not do so in full measure, leading eventually to Roy’s arrest in February 2014.

Today, Sahara’s empire lies strewn around different cities, a pale ghost of its epicurean past. Nowhere is its downfall more visible than at ‘Sahara India Point,’ a lot on SV Road in Mumbai’s Goregaon West, sandwiched between an old cowshed and an upcoming Zudio store.

Listed as Sahara’s Mumbai office, it hasn’t had a building for at least two years. All that remains is a boundary wall and a gate to keep prying eyes out. Next door, a parking lot doubles as a graveyard for company cars, a TV outside broadcast (OB) van among them.

“Do they also owe you money? Many people come here asking for the Sahara office,” said a security guard at the car showroom opposite the lot.

The signs in Mumbai

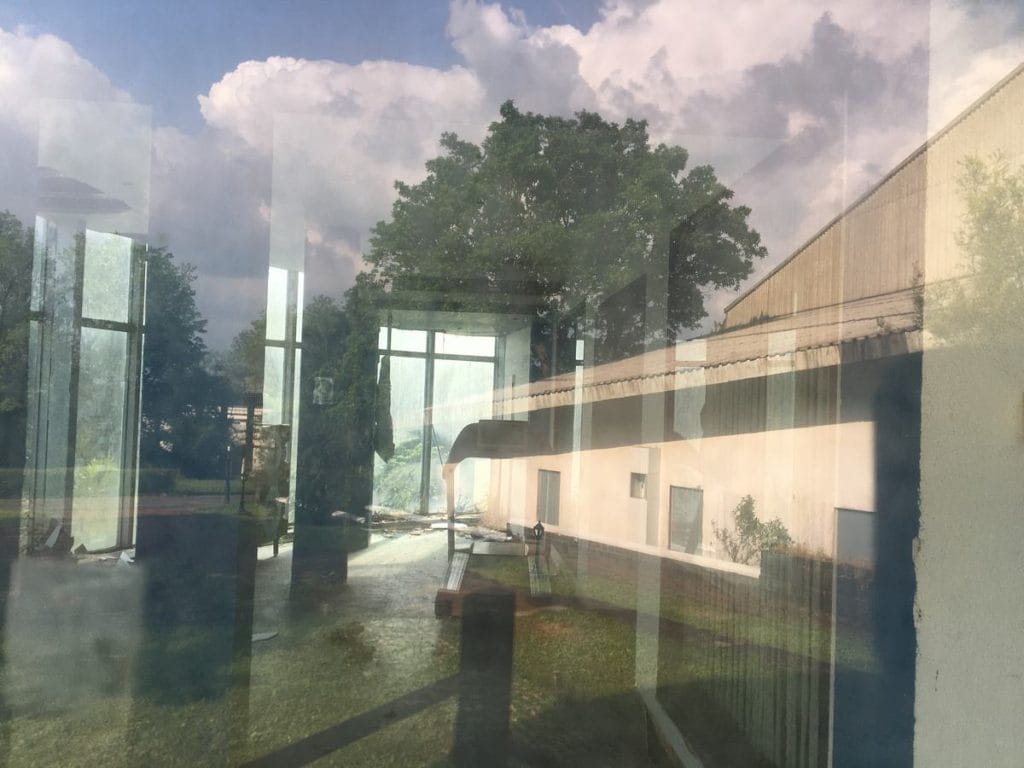

The once-impressive glass façade of the Sahara Star hotel looks faintly worn out. There was a time when it served as Sahara’s war room in the city , a monument to Subrata Roy’s standing in Maximum City’s power circles.

Once a wholly owned subsidiary of Air India, it was known as the Airport Centaur Hotel until it was sold to a Delhi-based group in February 2002 for Rs 83 crore as part of the Vajpayee government’s disinvestment drive. Sahara acquired it in October that year for Rs 115 crore. It became the venue for board meetings, to which Roy would arrive by a private elevator from the penthouse, according to Bandyopadhyay’s book.

It isn’t the only Sahara property in Mumbai perched on prime real estate. The office in Atlanta Building at Nariman Point, a key business district at the other edge of town, has been there since the 1990s. On the door of the second-floor office, a notice from the District Collector reads that the property has been attached at the request of the District Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission, Nainital, in connection with a dispute involving recovery of Rs 6.85 lakh.

Back in Lucknow, another Sahara monument, once the most coveted private residence in the city, is now but a shadow of the venue that once hosted the country’s most extravagant wedding in 2004.

The throne in Awadh

In Lucknow’s Gomti Nagar, where every second car wears a red or blue beacon, the massive pillared archway to Sahara Shahar stands out. At its centre sits a glass-encased temple dedicated to the group’s ‘presiding deity’: Bharat Mata, tricolour in hand, astride four fierce lions representing India’s four major religions.

Described by academic and former journalist James Crabtree in his book The Billionaire Raj as an estate “more akin to a Mughal fort than a mere mansion,” Sahara Shahar has a helipad, theatre, auditorium, a lakehouse on a floodlit artificial lake, and a seeming imitation of the White House where Roy held court every Saturday.

He (Roy) hosted one or two programmes each year, actors and actresses were flown in from Mumbai to impress politicians

-PL Punia, former principal secretary to Mulayam Singh Yadav

It was here that he hosted more than 10,000 guests for the double wedding of his two sons in 2004. The guest list included PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Deputy PM LK Advani, Vice President Bhairon Singh Shekhawat, and UP Chief Minister Mulayam Singh Yadav, besides a constellation of film stars and nearly all the players of India’s men’s and women’s cricket teams. A hundred members of the University of Warwick Symphony Orchestra, and their 140 instruments, were flown in to perform at the grand affair captured on film by director Rajkumar Santoshi. The Guardian put a price tag of £50 million on the week-long celebrations.

Sahara Shahar was reserved for the Roys and top Sahara executives, too exclusive for outsiders to enter. It was even a class apart from the group’s other high-end project, Sahara City Homes, for which Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bachchan appeared in an ad, smiling beatifically and calling it the place “where India lives.”

Much water has since flowed down the Gomti.

In the first week of October, about 150 estate employees stationed themselves at Sahara Shahar’s inner gates, demanding that their dues be cleared before the Lucknow Municipal Corporation (LMC) sealed the estate; at least two claimed they hadn’t been paid for four months.

An employer should meet employees to resolve their grievances, and you are running like thieves

-Member of the security team at Sahara Shahar

As the crowd gathered, Subrata’s wife, Swapna Roy, was quickly escorted away.

A Sahara employee who was part of the Roys’ security team since 1997 made no secret of his sense of betrayal.

“Someone had the duplicate key to the gate near the house that never opened. It was used to escort her out,” he said. “Malik aadmi ko karamchariyon se milna chahiye, tum swayam choron ki tarah bhagna chah rahe ho”— An employer should meet employees to resolve their grievances, and you are running like thieves.

Another household staffer, employed since 2001, was similarly disgruntled at the way Swapna Roy was hustled out surreptitiously— “chori chhupe tareeke se”.

“Senior Sahara officials told her what happened in Nepal could happen here; those guarding her were involved,” said the staffer, referencing the overthrow of KP Sharma Oli’s government in September.

Going by the staffer’s account, Swapna Roy had sensed the storm headed for her doorstep. “Madam ki packing pehle se hi shuru ho chuki thi”— Madam had started packing well in advance.

On 6 October, the LMC sealed all gates of Sahara Shahar, citing alleged violations of the lease deed and licence agreement. It said the land was originally leased to Sahara by the Mulayam government in 1995 to develop a residential colony, but was turned into a private estate instead, prompting the lease’s termination in 1997. A civil court later granted a stay in Sahara’s favour; the company has now moved the Allahabad High Court seeking cancellation of the LMC’s latest order.

ThePrint called and texted Rameshwar Prasad, Assistant Municipal Commissioner and head of the LMC’s property section, for comment but no response was received.

Even as the gates were being sealed in Lucknow, fresh trouble brewed elsewhere. In September, the Enforcement Directorate filed a chargesheet in Kolkata against Subrata Roy’s wife, Swapna, his son, Sushanto, and several Sahara officials in a Rs 1.74 lakh crore money-laundering case. It’s all a far cry from the group’s once-formidable political clout.

Back in the Sahara Group’s heyday, Subrata Roy was “close” to both the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party, with Amar Singh often acting as the conduit, according to PL Punia, a former Rajya Sabha MP who served as principal secretary to Mulayam Singh Yadav.

“He (Roy) hosted one or two programmes each year, actors and actresses were flown in from Mumbai to impress politicians,” Punia recounted.

However, former Uttar Pradesh DGP OP Singh insisted that contrary to the popular notion, he “felt no vicarious pressure” from Sahara in day-to-day police administration.

As for Mayawati and Roy, that wasn’t always a straight line. In 2008, bulldozers from the Lucknow Development Authority pulled down Sahara Shahar’s left boundary wall. The company contested the move in court and won. A Congress leader from the state linked the friction with Mayawati to a massive bike rally Sahara employees took out to accompany her arch political rival Mulayam to his oath-taking.

The tide began to turn after Roy’s arrest in 2014.

“Saharashri (Roy) treated everyone like family. It was never the same after he went to jail. Many who worked and lived inside didn’t even have money to go home,” said the security staffer. But it is only now that the fall of Sahara Shahar seems irrevocable. Roy died in 2023 but the march of law is unstoppable.

What led to Sahara’s unravelling?

In another part of Lucknow is the office of the daily newspaper Rashtriya Sahara. Like all Sahara offices, this one too has photos of Roy at every corner. A placard stuck between two elevator doors quotes ‘Saharashri’: “Pragati tabhi pragati hai jab vo nirantar evam gunavattaapoorn ho”—Progress is progress only when it is continuous and full of quality. The paper is one of the few arms of the Sahara Pariwar that is still operational; on a Sunday afternoon, none of the four-five employees present were willing to comment on the conglomerate.

At its peak, Sahara had 4,799 group companies across 16 verticals, over 1,000 offices, six lakh agents, and 10 crore depositors. About a decade ago, its assets were valued at roughly Rs 1.52 lakh crore, sprinkled across India from Jammu to Ernakulam and Vadodara to Siliguri. As Crabtree puts it, “Roy had holdings larger than any publicly listed Indian company.”

Sahara was, simply put, too big to fail. Until it wasn’t.

Roy was playing fraud on poor people. He made all of his money from chit funds. That money was never returned to the poor people, though the high and mighty got their returns

-Sharat Pradhan, political analyst

Sahara Pariwar started out as a chit fund company. One of its ventures was a savings scheme for the unbanked, registered as a Residuary Non-Banking Company (RNBC) in 1998.

The idea was simple: daily wage earners would deposit a small part of their income each day and get back their principal with a nominal added interest.

To recruit such ‘low-risk and no-risk’ depositors, it had an army of agents who combed small towns and countrysides, going door-to-door, and deploying the hustle of car salesmen. Those decades were heady with a heavy dose of the get-rich-quick drug that Indians were inhaling. It was a time when anything seemed possible — India was minting a new millionaire every other month. Greed was finally good in a country shedding its socialist skin.

And Sahara’s was an ambitious exercise in financial inclusion, until it ran afoul of the RBI, and later SEBI.

The dream started souring in 2008 when the RBI ordered Sahara India Financial Corporation to stop taking deposits from the public as it had strayed from the rules governing such deposit schemes. Sahara didn’t take it lying down. It called the RBI’s 2008 order “wanting in application of mind”. But Roy also knew when to back away. In a meeting with the RBI that year, he agreed to wind down the RNBC business by 2015, when the last deposit matured. Roy “gave up his empire with a smile,” Bandyopadhyay wrote.

This, of course, wasn’t the end of it. In 2012, SEBI accused the group of illegally raising funds through optionally fully convertible debentures (OFCDs) — debt instruments that pay regular interest payments and which can be converted into shares of the issuing company. The same year, the Supreme Court directed Sahara to refund around Rs 25,000 crore to depositors who invested in its OFCDs. It also ordered the company to hand over documents to SEBI.

In a famous case of malicious compliance, Sahara dispatched 127 trucks carrying 5 crore documents to the regulator’s doorstep in Mumbai. This was ostensibly to ‘prove’ it had paid back investors to the tune of Rs 20,000 crore. Years later, SEBI billed Sahara over Rs 41 crore as the cost of processing this mountain of haphazard paperwork. Ultimately, it was Sahara’s failure to comply that led to Roy’s undoing and arrest in 2014.

As for the crores of depositors, the government launched the Central Registrar of Cooperative Societies (CRCS)-Sahara Refund Portal in 2023 to help them claim their money. As of September 2025, the CRCS had disbursed Rs 2,314 crore to about 13 lakh depositors.

One reason why these depositors trusted Sahara was that it had every marker of credibility. Its logo was on the Indian cricket team jersey. It flew the tricolour on the Formula One circuit. ‘Big B’ was part of its Kartavya Council (grievances and suggestions cell). Among other members were Raj Babbar, Kapil Dev, Sourav Ganguly, Leander Paes, TN Seshan, and Russi Mody.

“The glitz and glamour attract the poor; they remain glued to Roy, who straddles the world of glamour and the other India that lives in Gorakhpur, Varanasi and Lucknow with consummate ease,” Bandyopadhyay pointed out in his book.

Stadiums to skyscrapers

Roy’s two obsessions, by his own admission, were real estate and sports.

For more than a decade, until 2013, Sahara’s logo featured on the jerseys of India’s men’s and women’s cricket teams. The group paid around Rs 300 crore for the sponsorship, which was over 10 percent of the total asking price in 2001. And in 2010, it bid Rs 1,700 crore for the Pune Warriors, then the highest bid for an IPL franchise. It was also the principal patron of Hockey India and owned UP Wizards.

It still owns Awadhe Warriors of Lucknow, one of eight teams in the Indian Badminton League, captained by Saina Nehwal until the 2017-18 season.

As for real estate, Sahara’s footprint extended across the country— Sahara States townships in Lucknow, Hyderabad, Bhopal, and Gorakhpur; Sahara Malls in Lucknow and Gurugram; and the 106-acre Versova plot in Mumbai now locked in dispute with SEBI.

Beyond sport and real estate, the group’s portfolio ranged from electric vehicles (Sahara Evols) and retail (Q Shop) to IT consulting (Sahara Next). It also had a media and entertainment arm, Sahara One, which produced hits such as No Entry and Malamaal Weekly, and the critically acclaimed Dor. It even bought an airline in 1993 and sold it to Jet Airways for Rs 1,450 crore in 2007.

Salaries of Sahara employees are sometimes late. It’s natural for employees to be a little concerned. The hope among many is that an Adani takeover will bring stability

-Sahara insider

Its hospitality arm, though, was the crown jewel. In 2010, Sahara acquired Grosvenor House hotel in London, followed two years later by 75 per cent stakes in New York’s Plaza and Dream Downtown hotels. It sold Grosvenor House in 2017 for £575 million to GH Equity UK, and its Plaza stake a year later to a Qatar state-owned fund for around $600 million.

Back in India, the Sahara Pariwar jewels that remain are Sahara Star and Aamby Valley City, now at the centre of the group’s distress sale.

A dream city, robbed of grace

East of Mumbai, the route to Aamby Valley City unfurls like a never-ending portrait of the Western Ghats, four different shades of green lining both sides. It was branded as India’s first planned hill city and launched in 2006 with a professional golf tournament. The township boasted a landing strip, three man-made lakes, an auditorium, a business centre, an 18-hole international golf course, and one-, two- or half-acre designer vacation homes for the gilded.

In keeping with Sahara aesthetics, two arches at Aamby Valley’s entrance set the tone. A little further on stands the ‘Bharat Mata point’, a 20-plus-feet offering to Sahara’s ‘presiding deity’, accompanied by an orb and a plaque carrying Roy’s memo to visitors.

A Rajkot businessman on vacation told ThePrint the brief to his travel agent was a trip to somewhere “quiet and less crowded”. Stay costs Rs 8,000 upwards per night depending on the choice of accommodation. Insiders say eight in ten dwellers are tourists, and on weekdays occupancy is about 60 per cent, rising to 80-90 per cent on weekends. “Diwali was sold out,” one insisted.

Yet the signs of disrepair are stark. Buildings lie abandoned, incomplete, or unused. Some roads lead nowhere, a few blocked by boulders or overrun by grass. Meanwhile Maybachs and luxury SUVs snake through uninhabited security posts. There’s the empty pool, in front of it a metal chair unmoved for so long that foliage has wrapped its arms around it. Wilderness has also claimed the dancing fountain. In the 10,000-acre township there is only a single thinly stocked daily-needs store.

Some guests seem a little taken aback by it all.

“For me it was my idea (to plan a trip to Aamby Valley), but there’s no maintenance. It appears like they haven’t cleaned it up for ages,” said Ajay Mahajan, a businessman from Ahmedabad on his first visit with his family.

The Supreme Court directed Sahara to put up Aamby Valley for auction in 2017, but there were no bidders. The next year, the court allowed a piecemeal sale overseen by a court-appointed liquidator. Two other hospitality groups now operate resorts on the property, though it is unclear whether they lease or own the land.

“I’ve been here 50 times since 2019,” said Mumbai resident Milan Vohra, whose chalet is under construction at Aamby Valley. “At the time the idea was very good; no one in India had thought of it.” He now laments the constant construction and loss of green cover.

Insiders admit financial woes make maintenance difficult. A former Sahara employee on vacation with his family acknowledged that upkeep had dipped since 2023, though staff “did a damn good job” under pressure. He still speaks fondly of when Roy pledged to foot salaries through the Covid lockdown

“Saharashri did for us during COVID what no one else could,” he added.

The township was the only means of income here; everyone could get work. It was a good time when Subrata Roy was there

-Anant, resident of Mulshi village near Aamby Valley

Now though, Sahara employees must contend with constant uncertainty.

“Salaries of Sahara employees are sometimes late,” said another insider. “It’s natural for employees to be a little concerned. The hope among many is that an Adani takeover will bring stability.”

But still, a sense of loyalty to Roy prevails. He may have spent nearly 800 days in Tihar’s Jail No. 3 but he did play the part of Sahara Pariwar’s ‘sutradhar’ (stage manager) from its inception until his death in 2023 at 75. A former member of the National Cadet Corps, he built his own army, and was at one point presumed to be India’s largest employer after the Railways.

Around the partial necropolis that Aamby Valley is, Roy is still seen as someone who brought opportunities with him.

“The township was the only means of income here; everyone could get work. It was a good time when Subrata Roy was there,” said Anant, a fifth-generation resident of Mulshi village on the fringes of Aamby Valley and the owner of a makeshift daily-needs store in his front yard.

Business is no longer what it used to be. “Footfall (of tourists) is now lower than pre-COVID levels,” Anant rued.

Back in Lucknow, wax seals, locks, and seizure notices appear to be a running theme in Sahara-owned real estate.

Its office in Aliganj, the white-and-blue Sahara India Bhawan, was sealed by the UP Real Estate Regulatory Authority in July. A skywalk links it to the office of the company’s life insurance arm, Sahara India Centre, which was sealed by the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation during its investigation into unpaid provident funds and pension dues.

“In a few days’ time, only they will be left here,” said a former Sahara employee on condition of anonymity, pointing to a troop of monkeys nearby.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)