New Delhi: Just months after the BJP declared it would provide housing for slum dwellers in Delhi, 39-year-old Dinesh Kumar Verma watched in horror as bulldozers tore down his home in Wazirpur’s Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony.

“When the Bharatiya Janata Party campaigned here, they raised slogans of Jahan Jhuggi Wahan Makan (where there is a slum, there will be a house),” said Verma. “Instead, their slogan should be Jahan Jhuggi Wahan Maidan (where there is a slum, there will be a field).”

A sea of broken bricks surrounds the railway line that loops around Wazirpur Industrial Area, a zone in Northwest Delhi filled with slum colonies. Residents dug through the rubble with their bare hands to search for precious pieces of their identity. They pulled out their special Congress-era ID cards, Aadhaar, electricity bills, survey slips, ration cards, and voter IDs—papers that offered a semblance of legitimacy to their homes.

Since the BJP came to power in Delhi in February 2025, slum demolition drives have ramped up, with over 300 “illegal dwellings” razed last month in Jailorwala Bagh and Wazirpur alone. The Delhi Development Authority (DDA), the railways, and municipal bodies cite court orders directing the removal of “illegal encroachments” from public land.

But in Wazirpur, where migrant workers from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh began arriving in the 1980s, these settlements grew with political blessings. Their patron saints were leaders like Congressmen Deep Chand Bandhu and HKL Bhagat, who helped secure water connections and electricity lines. Over the decades, families built brick homes and collected documents meant to protect their right to live there. Now, those papers offer little protection. It’s another example of how slums are built, given recognition, and removed depending on who’s in power, according to local activists.

Older residents recall how one party would facilitate water connections, while another would promise rehabilitation, only for those gains to be rolled back when governments changed. In Mumbai too, the fate of slums often hinges on the unspoken nexus between politicians, residents, and officials.

The settlements were part of the city’s growth story but their legal status was left hazy.

“Because slums are planned illegalities, from time to time demolitions have happened,” said Akash Bhattacharya, a historian and trade union activist, at a protest against slum evictions outside Jantar Mantar in Delhi.

Most jhuggis in the national capital, he pointed out, were established during Congress dispensations and allowed to stay during the Aam Aadmi Party’s rule.

“Since the land is under the central government, whenever BJP is in power there have been demolitions,” Bhattacharya added. “These slums were never a vote bank for BJP like they have been for Congress or AAP.”

Also Read: The idea of Noida. The bad boy of NCR, Mall of India swag, a culture vacuum

Farms to factories to jhuggis

The calloused hands of workers in Wazirpur Industrial Area are covered with a shiny metallic residue after long shifts in the nearby steel factories. Bowls, cutlery, pipes, and coils spill into the narrow lanes lined with garbage piles. The sewage drains are clogged, with many jhuggis built on top of them.

Fifty years ago, this was barren agricultural land on the edge of Delhi. But in the mid-1970s, the area was designated as an industrial zone as part of a government plan to decongest the city’s core from polluting industries. As steel factories sprouted up, labour poured in from surrounding states, particularly Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

The majority of the people here are from Uttar Pradesh or Bihar. Around 2 per cent come from Madhya Pradesh. They have been living here for generations, with many of their children and now grandchildren living in the same colony.

“Eighty per cent of the factories here produced steel goods for the railways. At the time, we would be paid Rs 240–300 for eight hours of work,” said Indrajeet Yadav, who moved into Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony in 1980.

Now in his 80s, Yadav, dressed in a crisp white kurta, carries himself like an elder statesman of the colony. He has seen the area change block by block, decade by decade. He started out as a factory supervisor, became a labour contractor, and eventually shifted to full-time local politics in the 2000s as a member of the Janata Dal (United) and president of the colony’s Residential Welfare Association (RWA).

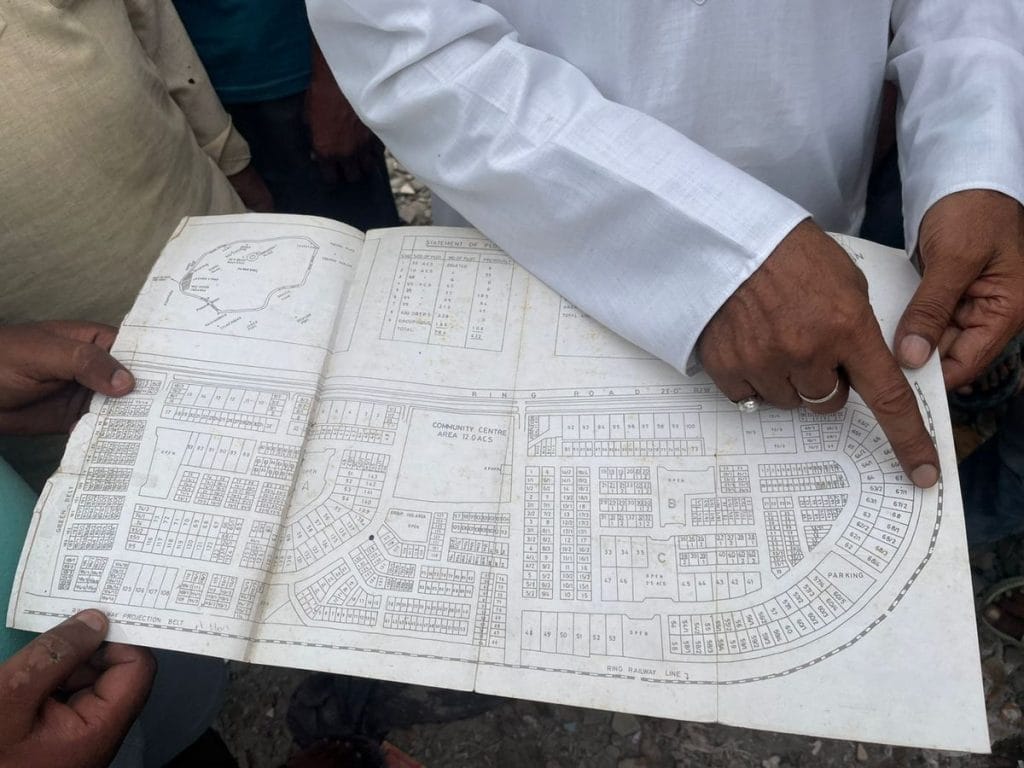

When the demolitions began in June 2025, most affected residents turned to him—their memory-keeper and link between the jhuggis and political authorities. He was whisked from one lane to another as people pleaded with him to save their homes. He has also written a letter detailing the history of the colony and the documents its residents have received over the years. He plans to distribute it within the colony and send copies to DDA officials, municipal corporations, and MLAs.

“I have printed out 200 of these letters,” said Yadav, handing over a copy and pointing to the various RWA members listed on the letterhead. “These people voted for various parties—BJP, Congress. But we have all come together to condemn this demolition.”

Yadav’s own house, spared from the day’s demolitions, stands at the periphery of the industrial area, around 25 feet away from the railway line.

What started off as a planned industrial zone became a hodgepodge of informal settlements as labourers gradually occupied plots close to their factories.

“The story of a slum is always a story of labour,” said Mukta Naik, an architect and urban planner at the National Institute of Urban Affairs. She added that when industrial areas were planned, housing for workers was never taken into consideration. Informal settlements surrounding factories filled that gap.

In the 1980s and 1990s, labourers arrived in droves from rural heartland states. Local agents in their villages would connect them to bigger contractors sourcing a workforce in the city’s industrial areas, according to Naik. Quiet agreements would then be made with local authorities to allow labourers to occupy space near the factories.

As Delhi grew, Wazirpur became part of the city’s main grid. Several factories shut down in the 2000s as pollution controls tightened. But the residents didn’t leave, even as many started working as delivery agents, fruit sellers, or auto-rickshaw drivers.

“The majority of the people here are from Uttar Pradesh or Bihar. Around 2 per cent come from Madhya Pradesh,” said Yadav. He added that the area housed the “poorest of the poor” from these regions, many of whom were Dalits who faced caste discrimination in their villages back home.

“They have been living here for generations, with many of their children and now grandchildren living in the same colony.”

As the colony expanded, the houses evolved as well. Walls changed from tin to brick, roofs from tarp to concrete. These home improvements were all undertaken by the families themselves.

“The materiality of the settlement is both a measure of how long it has been there and how confident the residents feel of not being evicted,” said Naik. She pointed out that even small signs, like water tankers from the Delhi Jal Board, give residents a sense of legitimacy.

But this sense of belonging is fragile.

One of the first signs of being part of the mainstream came in the 1980s, when water connections arrived, largely due to the efforts of Deep Chand Bandhu, a Congress leader who later served as Wazirpur’s MLA from 1993 to 2003.

Shaky legal ground

Even with water pipes, metered electricity, and pucca houses, Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony was never truly on firm ground.

The tenuousness of its existence is evident in the way it is classified, both in government records and policy papers.

The slum clusters in Wazirpur Industrial Area are officially categorised as jhuggi-jhopri clusters (JJCs)—informal settlements built without permission on public land. A 2015 paper by the Centre for Policy Research, Categorisation of Settlements in Delhi, describes JJCs as “squatter settlements”, built on public land owned by agencies like the Railways, DDA, or MCD. Referred to as ‘encroachments’ in official parlance, JJCs have the “least secure tenure” among different types of informal settlements and are the “most vulnerable to demolitions and evictions”.

Home to 1,470 households, Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony is listed as one of 675 slum clusters identified by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB), set up in 2010 to provide civic amenities and oversee resettlement of JJCs. The list includes each colony’s location, number of households, and the land-owning agency. According to it, Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony is on Railway land.

While some JJCs are formally “notified” under the Slum Areas (Improvement and Clearance) Act, 1956—granting them legal recognition and access to utilities, redevelopment, or resettlement—those on central government or railway land, like this one, are typically not. Residents, therefore, can be evicted without resettlement.

DUSIB also maintains a separate list of 196 colonies surveyed under the Delhi government’s Mukhyamantri Awas Yojana (MMAY), which promises rehabilitation within a 5 km radius. But Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony doesn’t appear on that list, most likely because the scheme only applies to land owned by the Delhi government.

Despite the ambiguity around the colony’s legal status, however, residents gradually secured basic utilities over the years.

Meters, bills, and promises

One of the first signs of being part of the mainstream came in the 1980s, when water connections arrived, largely due to the efforts of Deep Chand Bandhu, a Congress leader who later served as Wazirpur’s MLA from 1993 to 2003.

“When Bandhu was with MCD, he helped us get water connections. They built smaller pipes to the colonies from the much larger ones that were serving the factories in the area,” said Yadav.

The avuncular Bandhu, often pictured in plain grey or white bandh galas, entered politics in 1971 as a municipal councillor. He rose through the ranks of the MCD and became Deputy Mayor in 1984. Over the next two decades, he served as president of the Delhi Pradesh Congress Committee in 1994-96 and was appointed minister of Industry and Environment in 2001 under Sheila Dikshit. In 2013, a decade after his death, a 200-bed government hospital was named after him in Ashok Vihar, part of the Wazirpur constituency he represented.

“But electricity was a bigger problem,” said Yadav.

Until the mid-1980s, residents lit their homes with diyas and oil lamps. In 1984-85, Bandhu and Congress leader Hari Krishan Lal Bhagat helped the colony get electricity, though it was unauthorised and diverted from other sources.

A greater sense of permanence on that front came a good two decades later.

“In 2004, we finally got meters under Sheila Dikshit,” said Yadav, pointing to the semi-rusted meter at the threshold of his house. In 2002, Delhi privatised electricity distribution, opening new markets for power companies.

In 1985-86, when Rajiv Gandhi was Prime Minister, the DDA conducted a survey of all slum colonies in the city

Barkhu, resident of Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony

Today, Tata Power Delhi Distribution—a joint venture between Tata Power and the Delhi government—supplies electricity to the slum clusters in the area.

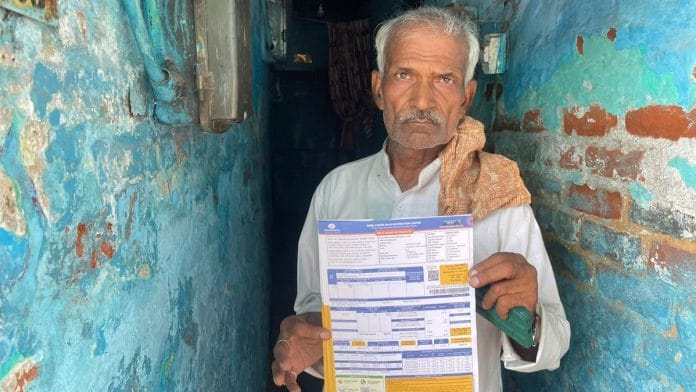

The standard Tata Power bill includes the address of the jhuggi, the connection type (‘permanent’ for most houses) and a “JJ Clusters-Metered” tariff category, referring to a subsidised rate.

For many residents, these bills became a kind of paper shield, proof they had a bona fide home here.

“In our time, we gave out regularisation certificates to over 900 unauthorised colonies,” said Pawan Khera, head of the Congress’s media and publicity department. These certificates, he claimed, enabled municipal services to reach slum areas. Technically, however, this move applied only to “unauthorised colonies” (which are built on subdivided agricultural land and usually characterised as ‘semi-legal’) and not JJCs under DUSIB’s jurisdiction.

Still, residents of Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony and nearby slums accumulated various documents over the years that gave them a sense of security, reinforced by political promises.

Those assurances mostly held during the Congress and Aam Aadmi Party years. When demolitions did happen, they were largely carried out by central agencies or by court orders. During the Congress’s tenure, affordable housing units were also built under various slum rehabilitation schemes.

“The biggest shame is that we had built infrastructure specifically for rehabilitation, which is lying vacant,” Khera told ThePrint. “After our 15 years in Delhi (1998-2013), you had Arvind Kejriwal as Chief Minister and Narendra Modi as Prime Minister, but no new flats were allotted in these buildings.”

The AAP government, though, tried to position itself as a defender of slum dwellers once it came to power in Delhi.

In February 2015, AAP banned the demolition of all slums built up to June 2014, prompted by the flattening of bastis in Wazirpur and Rangpur Pahari on the day Kejriwal and his cabinet were sworn in. But later that year, in December 2015, the Railways razed 1,200 units in Shakur Basti, triggering a fresh set of confrontations between AAP and BJP.

But for Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony, decades of political patronage and the edifice of paperwork proved meaningless on a humid June morning when the JCBs rolled in.

Slum politics

One of the oldest residents of Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony, 71-year-old Barkhu from UP, clutches a clear plastic folder with photocopies of all his documents. He managed to salvage it from the rubble after his house was demolished. As a small crowd gathers, he carefully lays out each paper, meticulously organised just in case any officials come asking.

“In 1985-86, when Rajiv Gandhi was Prime Minister, the DDA conducted a survey of all slum colonies in the city,” said Barkhu, pointing to the photocopy of his survey certificate. His jhuggi number, occupation, date of arrival (1980), and ration card number are all listed. On the back is a signed declaration stating that he owns no other land or house in Delhi and has never been allotted a plot or flat by any authority.

Indrajeet Yadav chimed in, recalling that at the time, there were 12 polling booths serving 15,000 voters. Each person was given a red, yellow, or green ration card, depending on their income level. At the time, ration cards weren’t just for accessing subsidised food, but also served as proof of residence. Today, according to Yadav, there are 40 polling booths for over 45,000 voters here.

The spectre of demolitions always hung over the cluster, but in those days, say residents, there was more hope of recompense.

One of the earliest demolitions in the Wazirpur Industrial Area took place in 1988-89, when 180 houses in Shaheed Sukhdev Nagar (SSN), a colony adjacent to Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony, were demolished to make space for a new railway line. Barkhu and Yadav claimed that Deep Chand Bandhu, HKL Bhagat, and a few others helped rehabilitate 135 families by ensuring they received 35 gaj of land each in Bindapur, West Delhi.

“Those people didn’t have to spend a single rupee. Government cars took them to those plots,” said Yadav.

A year later in 1990, when VP Singh was Prime Minister, another survey was conducted jointly by the DDA, MCD, and Indian Railways. Across Delhi’s slum clusters, residents were issued an identity card and a “token”—an aluminium plaque they could place outside their jhuggis.

Rust and time have nearly destroyed Barkhu’s token, but his identity card has survived. Both were meant to protect residents of slums from evictions or demolitions. But as power at the Centre changed hands, the fate of residents was once again thrown into uncertainty.

“In 2000, when Atal Bihari Vajpayee was Prime Minister, demolitions took place all over Delhi,” said Yadav, unravelling his turban to reveal a scar from a police lathi charge. “We sought the help of VP Singh, who immediately called up then Railway Minister Mamata Banerjee and Urban Development Minister Jagmohan Malhotra for a solution.”

In Wazirpur, Indrajeet Yadav had a part to play in enlisting VP Singh’s support in 2000. By this time, he had become a member of the JDU, which opened doors he earlier would never have had access to.

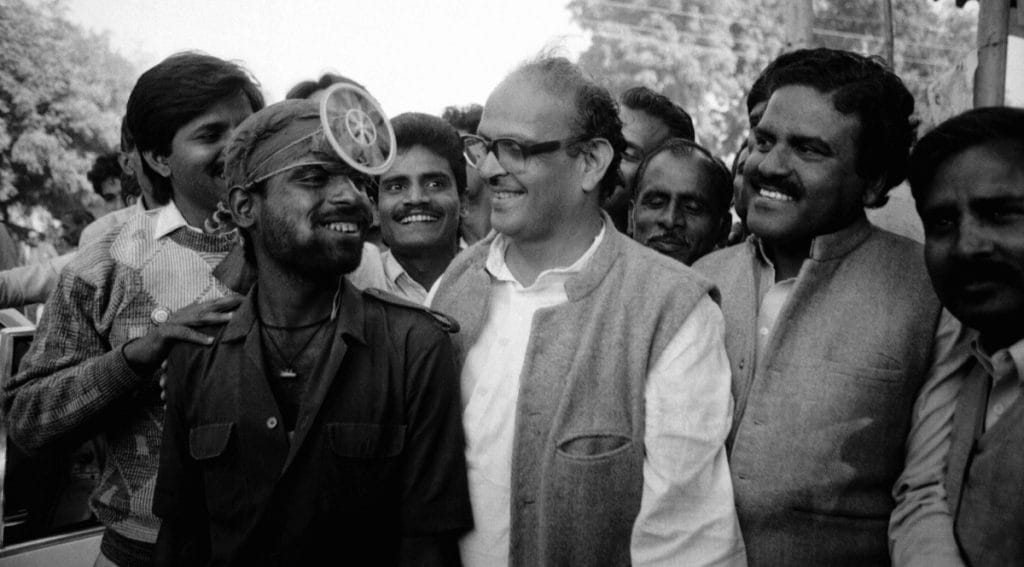

VP Singh’s fight

During Vajpayee’s tenure from 2000 to 2004, slum demolitions continued intermittently across Delhi, particularly on land owned by central government agencies. VP Singh took up cudgels against the NDA government on this issue in a big way, appearing at protests in jhuggi clusters from Wazirpur Industrial Area to Arjun Nagar. “Policemen face VP Singh’s ire over demolition of slums,” said one 2001 headline about an Arjun Nagar demolition. Another 2000 article described his anti-demolition campaign as a “political comeback plank.”

In Wazirpur, Yadav had a part to play in enlisting Singh’s support. By this time, he had become a member of the JD(U), which opened doors he earlier would never have had access to. He visited Singh’s residence with a group of eight jhuggi residents, but the former PM was in Apollo Hospital at the time. Upon hearing about the plight of slum residents, however, Singh made the call to Banerjee, Malhotra, and Vajpayee. He was initially rejected, according to Yadav, but took the fight to the ground.

At 8 am on 24 March 2000, Singh reached Shaheed Sukhdev Nagar, the slum colony adjacent to Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony. Over the next three days, he shuttled between the slum colonies and the hospital, his health precarious but resolve as strong as ever. It was at a park in Wazirpur Industrial Area where Singh began the first of several dharnas over the years. Yadav said VP Singh even spent some time at his house.

In May that year, Singh also organised a rally at Red Fort, attended by the likes of former PM HD Deve Gowda and CPM leader Harkishen Singh Surjeet.

“You cannot come down one night and uproot them, and our rally and rath yatra is to protest against [these] insensitive drives,” Singh said. “There must be a transparent policy for the poor in terms of rehabilitation and settlement.”

VP Singh’s dharnas attracted major opposition parties, including the Congress, Rashtriya Janata Dal, and CPI(M). Eventually, a solution was reached in 2000: the Railway Ministry under Banerjee would send funds to DUSIB for removing encroachments and rehabilitating residents living on railway land. This finally happened a few years later.

The National Green Tribunal would later criticise the Delhi government for not using Rs 11.25 crore since 2003-2004, while DUSIB and Railways traded blame for the delay. However, some progress was made.

From 2004 to 2009, the Delhi government under Sheila Dikshit built affordable housing units in Bawana, Narela, Bhalswa, Rohini and other areas around Delhi. Dikshit’s flagship scheme—Rajiv Ratan Awas Yojana (RRAY)—was launched in 2009 to assign these low-cost flats for those displaced by the demolition drives.

“Sheila Dikshit cared deeply about the residents who were rehabilitated under the scheme,” said a secretary who worked under Dikshit for two years and did not wish to be named. “She checked with us whether there were schools, basic facilities set up for the residents. This forced officers to actually visit these colonies and write detailed reports.”

The people living in those flats have benefits such as bus stops, malls, markets and even factories nearby for work opportunities, according to Yadav.

“But since the Aam Aadmi Party came to power in Delhi, and after that the BJP, there have been no new allotments in those flats. They are lying vacant and getting spoiled,” he added.

The interplay of slums and politics, though, isn’t just a Delhi phenomenon.

“No slum will be demolished without first providing permanent housing,” Delhi CM Rekha Gupta had said last month, adding that most actions are based on court orders. However, many jhuggi residents say there have been left homeless.

A parallel in Mumbai

Slum clusters in Mumbai mushroom in similar ways to those in Delhi. Kamala Raman Nagar (KRN), a dense settlement spread over 12 hectares in Govandi, lies right next to Deonar dumping ground, one of the oldest and largest landfills in the city.

With a population of approximately 40,000, it is one of more than 250 slum pockets in Govandi, which falls under the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation’s (BMC) M-East ward, among the poorest administrative divisions in the city.

In Mumbai, slums built until 2000 have been regularised under the Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance and Redevelopment) Act. For houses built between 2000 and 2011, residents must pay Rs 8 lakh for new homes under the government’s slum redevelopment policy. Despite various schemes and regularisation attempts, these slums continue to grow unchecked and lack basic services.

The area is governed completely by local politicians and their lackeys. They give contracts to their own people and operate on commission—whether that is desilting work or providing electricity

– Sohail Khan, an independent activist in KRN

“When a slum is built, some are ‘notified’, while others are ‘census slums’,” said Vinayak Vispute, deputy additional commissioner, Encroachment, BMC. “For those slums that don’t fall in either category, our colony department takes action on them.”

Kamala Raman Nagar, a ‘notified’ slum, was once located on the city’s fringes. It became a Muslim-dominated ghetto after the 1992 Bombay riots. Today, it’s primarily home to Muslims, Dalits, and other marginalised groups. Most work in low-paying jobs—delivery drivers, labourers, construction workers. Like in Wazirpur, the cluster saw a rapid, unregulated expansion.

Kallo Javed Akhtar, 40, has lived in Kamala Raman Nagar since childhood. She recalled a creek flowing through the area in the 1980s, which was gradually filled in as more people moved in. In Delhi too, slums often come up over open water bodies and drainage channels. These are usually the first slums to be destroyed in demolition drives because of the direct effect they have on sanitation in the immediate and surrounding areas. But the action usually comes after years of authorities turning a blind eye.

“If the slums are expanding, if anyone is building more floors, would the BMC not know?” said Faiyyaz Alam Shaikh, a social worker in Kamala Raman Nagar. “They regularly do rounds in this area. They should be taking preventive actions.”

Sheikh alleged that some BMC officials were in cahoots with local politicians, leading to rampant corruption. According to him, local building contractors operate without any licenses, little experience, and don’t follow any technical specifications to build slum houses.

The civic management is in shambles because of this nexus, claim local activists.

“Even the desilting of drains or garbage picking doesn’t happen. The area is governed completely by local politicians and their lackeys,” said Sohail Khan, an independent activist in KRN. “They give contracts to their own people and operate on commission—whether that is desilting work or providing electricity.”

Since 2009, the constituency has been represented by Abu Azmi of the Samajwadi Party, now in his fourth term. Before that, it was held by the Congress. During the last BMC term (2017–22), five SP corporators represented the area, where the BJP has never had much of a foothold.

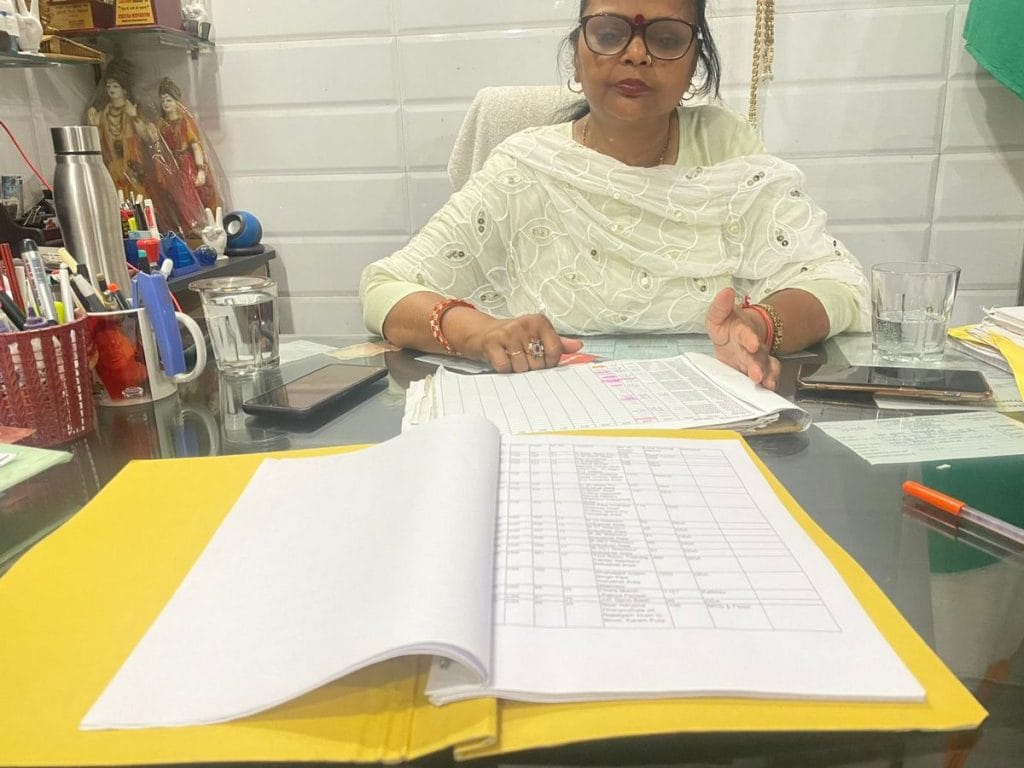

Back in Delhi, Chitra Vidyarthi, the MCD corporator for Wazirpur from the Aam Aadmi Party, echoed that sentiment. She accused the BJP of targeting slums because they expect little political return from these areas.

But residents of Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony say they feel let down. Many had voted for the BJP because of the promise of building formal housing through the in-situ rehabilitation scheme ‘Jahan Jhuggi Wahan Makan’.

At Jailorwala Bagh, another jhuggi cluster in Wazirpur, Anoop, a 34-year-old hospital ward boy, sat on a pile of bricks that was once his home. He took out his phone and played a video clip of Chief Minister Rekha Gupta promising that no jhuggis would be razed.

“No slum will be demolished without first providing permanent housing,” Gupta had declared last month, adding that most actions are based on court orders. In June, DDA said 1,078 families from the JJ cluster in Jailorwala Bagh were relocated to Swabhiman Apartments, 567 were found ineligible, and that the Delhi High Court had granted stay orders to around 250. Many residents, though, are still homeless.

“Fifty per cent of the people living in this colony have no other home, either in their village or in the colony,” Anoop said, adding that Jailorwala Bagh doesn’t have any local leader like Indrajeet Yadav to fight for them. “We don’t know who to turn to. Where will we go?”

Some older residents of Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony have saved up enough to buy plots in Ghaziabad, Sonipat, and Narela. A few have already moved out, renting out their jhuggis to newer arrivals.

Also Read: Both BJP & AAP promised ‘jahan jhuggi, wahan makan’, but Delhi slum redevelopment sees slow take-off

Lives in transition

On the other side of the railway tracks, Dinesh Kumar Verma has salvaged what remains of his old electronics store. Televisions, circuit boards, wires and mobile phone screens lie in covered boxes. The demolitions erased not just his home, but his entire livelihood.

He bought the house in 2010, but had been living in Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony for years before that.

“I was staying on the floor above, my electronics repair shop was on the ground floor,” said Verma. “They kept changing the distance from the tracks they were going to demolish. First it was 6 feet, then 15 feet. Now they are saying it will be 25 feet.”

On the rooftops of houses that remain, crowds gather to watch the chaos unfold below. Some are homeowners who have lived here for generations. Others are tenants renting anything from a single room to an entire house, depending on their family size. Part of Yadav’s own house has been converted into a mobile recharge shop, its walls well within the 25-foot radius the authorities are now clearing. He fears it’s only a matter of time before it’s gone too.

The colony is by no means cut off from the rest of Delhi. Azadpur metro station lies across the railway tracks, buses reach the colony’s edge, and an MCD primary school stands at the heart of the area. But in many ways, Chandra Shekhar Azad Colony is a self-sustaining microcosm of the city.

Outside the cramped lanes that run through the colony, on the pothole-ridden roads that connect it to the rest of the city, shops sell everything from milk and meat to plastic buckets and cycles. Residents don’t need to leave the colony for daily essentials—there’s usually a neighbour selling whatever they need.

It’s a tightly knit community. A vegetable vendor on one of the main roads stops Yadav to ask for an update on the demolitions. A teenage boy runs past, but not before pausing to touch Yadav’s feet.

As the last of the bulldozers retreat for the day, a crowd forms around Yadav as he reads aloud the letter he prepared on behalf of the RWA. Each slice of colony history receives nods of approval from residents, many old enough to remember the promises of the late ’80s and early ’90s. Once done, the crowd disperses, and Yadav folds the letter with care. Like the stack of ID cards and papers he has shown before, it’s one more document, one last plea, to stand in the way of the bulldozers.

But there are slower, subtler changes afoot as well.

Yadav’s younger son, now standing on the rubble of houses torn down, works at the mobile recharge shop, but his other three children have moved away.

“My elder son works at a local bank now, as an office boy,” said Yadav proudly, adding that both his daughters are married and living elsewhere. “All the young people from this area are trying to get out.”

It’s not just the young. Some older residents have saved up enough to buy plots in Ghaziabad, Sonipat, and Narela. A few have already moved out, renting out their jhuggis to newer arrivals.

The new tenants, some fresh arrivals from UP and Bihar, have started their own journeys up the socio-economic ladder, working as fruit and vegetable vendors or auto-rickshaw drivers.

“Over 70 per cent of the fruit sellers in Azadpur mandi come from our colony,” said Yadav. Depending on room size, the tenants pay anywhere between Rs 3,000-5,000 a month to their jhuggi-dwellers-turned-landlords—a sliver of social mobility even as the ground shifts beneath them.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

One can sympathise at a human level. However:

India is the world’s most populous nation with no population control measures whatsoever; heavily deforested, environmentally degraded, severely polluted (Delhi the most polluted city in the world); we are a nation of scofflaws and jugaad in the negative sense of the word, inching towards the limits of non governance.

Unless we at individual level make concentrated effort to be law abiding and the govt enforces law impartially, we are enroute to becoming what a US Ambassador to India once famously described India as – a functioning anarchy.

Govt land, illegal construction encroaching onto adjacent railway tracks etc. If people are going to exchange their votes for squatter rights and then use jugaad to game the system to make pukka houses and obtain documents, the underlying premise is malafide.

There is a saying – In a democracy people get the govt they elect and they deserve.