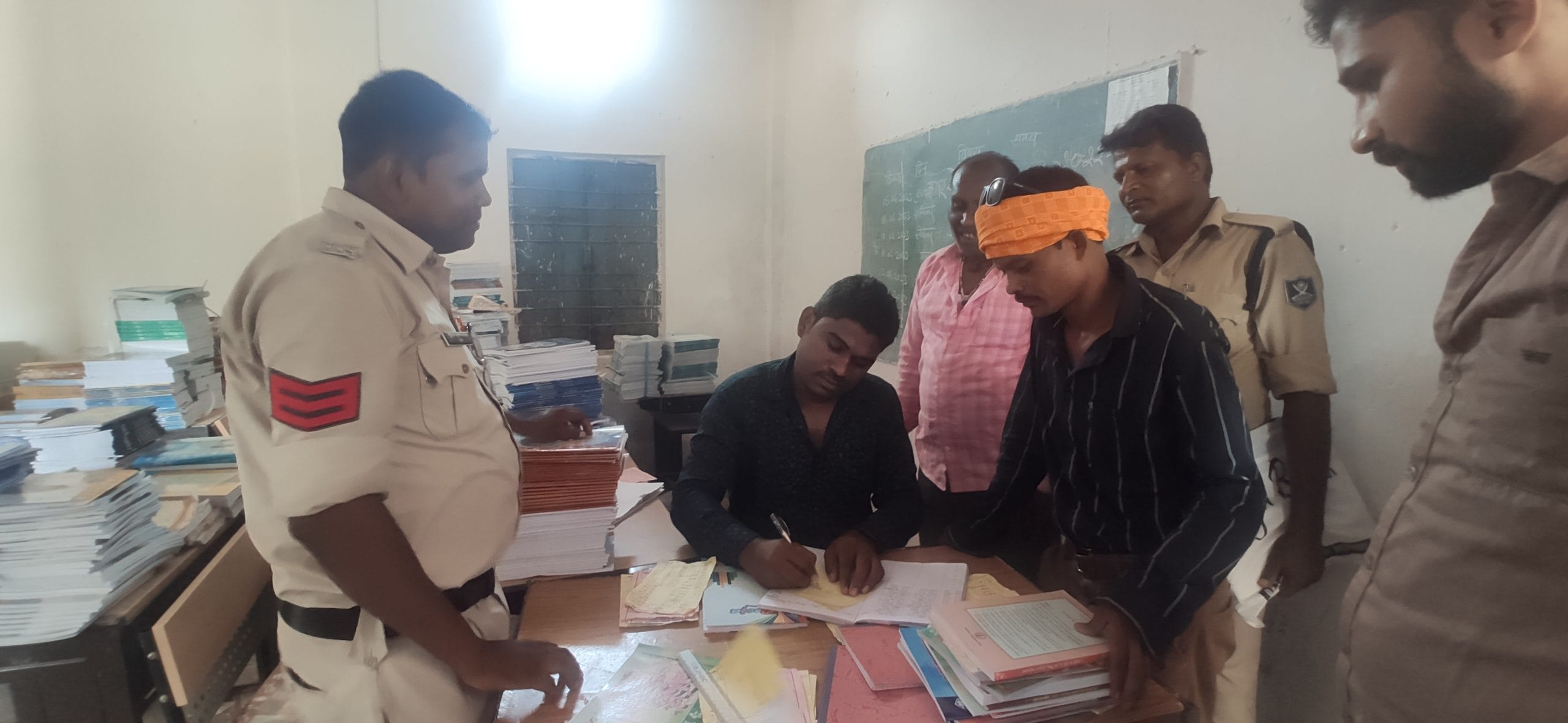

Karaundi: A team of six policemen sits patiently near Dashmat Ravat, 30, on the four charpoys laid out at his under-construction house in Madhya Pradesh’s Sidhi district to record his statement in the urination case against local politician Pravesh Shukla. Station house officer Pawan Singh of Behri police station is struggling to get a server connection on his phone. Ravat gets up impatiently. He has work to do. He can’t wait forever for the policemen to finish. He waves them away by saying, “I will come tomorrow and get the statement recorded, now I have to go to the school to get my son’s admission completed.”

Listening to Ravat’s request, the police team headed by Deputy Superintendent of Police Priya Singh agrees to visit again at a convenient time. “You should have told earlier, we would have come another day. Never mind, at least I got to meet you this way,” Singh says.

In the fortnight since the video of Pravesh Shukla urinating on him became national news on 4 July, Ravat has tasted both fame and fear in equal measures. He is now enjoying a mini-stardom in and around his village. People want photographs with him, policemen are unusually polite and he has the whole establishment waiting to assist him. Two widely-shared videos have brought him more than his share of 15 minutes of fame in this quaint village. His life has been turned around dramatically and too quickly. But beyond the fame also lurks a fear of a future of retribution and resentment by the privileged caste groups.

A day after the video reached every corner of the internet, Ravat was summoned by Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan to Bhopal where the CM washed his feet, called him his Sudama and assured all possible help. A week since then, Ravat has received Rs 6 lakh as compensation, a pucca house under PM Awas Yojna is being constructed alongside his kuccha house, a hand pump has been installed, while two officials each from the revenue and police departments have been placed outside his house for his security. These officials work in two shifts of 12 hours each.

Listening to Ravat’s request, two head constables—Yugal Ravat and Suresh Ravat, who are deployed for his security—take him and his son to school.

With a gamcha (towel) tied as a turban and a pair of sunglasses over his head, Ravat with his son Rahul hopped on Suresh’s bike to head to school.

Curious eyes of shopkeepers in the village follow Ravat as he zips through the main market of Kubri village on the head constable’s motorcycle. Higher Secondary School Sapahi is located merely 200 meters away from the accused Pravesh Shukla’s house.

Some greet the policemen with folded hands, while others call out to Ravat and some others simply smile at him. Politely acknowledging their greetings, Ravat walks confidently with his sunglasses on and is escorted by police constables. Ravat is wearing a blue shirt paired with brown pants, an outfit gifted to him by a tribal leader who had visited him after watching the video. The long brown pants make him look tall.

At the Higher Secondary School Sapahi, three teachers sit inside a room that has a board with ‘admissions’ written on it.

The unusual team of two policemen escorting a man for his son’s admission makes many like Prima Singh, a school teacher in the admission team curious. “Why are so many people accompanying one student,” Singh asks looking over the admission documents.

But when informed that the boy is the son of Dashmat Ravat, Singh requests to see Ravat once. “Who is Dashmat, call him inside. Let us also see how he looks,” she says. Over the next five minutes, Rajesh Khushwaha—who heads the admission team—scrutinises documents produced by Ravat before asking him to go ahead and pay the fees. But before Ravat could head out, Khushwaha asks for a photo with him.

“The whole incident became so big that it is being discussed in the entire country. We also want to be a part of it through our small contribution,” says Rajesh.

Also read: MP’s Nepanagar forest is the new battleground. IPS, IFS, tribals, activists, mafia at war

At villagers’ mercy

Even as Ravat does the formalities for his son’s admission, he is worried if the village will be accepting of him. And if he will find work with ease and live peacefully.

“The chief minister has done all this, called me his Sudama, but if he could give me a government job, then I won’t be left at the mercy of the villagers to find work. Pravesh’s friends and neighbours ask me to forget what happened and withdraw the case since the government is taking action for the wrong done by him. But because of this, people might not let me get any work in the village,” says Ravat.

Pointing to the fields surrounding his kuccha house, Ravat adds, “What can I even do, everything belongs to them (dominant caste villagers).”

The village’s sarpanch, Ganga Prasad Sahu, echoes Ravat’s fear.

“Now the situation in the village is peaceful. But Dashmat’s fear of villagers pressurising him into withdrawing the case is real. Two days ago, he asked me to get the construction work of the toilet at his house expedited. He is scared of going into the fields. It cannot be disputed that Pravesh belongs to a powerful family and can influence others but if that situation comes, Dashmat can get work outside the village, one cannot influence all.”

The Congress had alleged that Shukla is a BJP worker and representative of MLA Kedarnath Shukla. But the MLA had denied it. “No matter what Kedarnath Shukla says to distance himself but Pravesh worked as his representative in the village,” says Vidyakant Shukla, Pravesh Shukla’s uncle.

After the urination incident came to light, the district administration demolished a portion of Shukla’s house, citing illegal encroachment. The village’s Brahmin community has come forward in his support, calling the demolition politically motivated and unjust. Shukla’s family has also received about Rs 2.5 lakh as monetary help from Akhil Bhartiya Brahman Samaj (ABBS) headed by Pushpendra Mishra.

With support from the ABBS, Shukla’s wife Kanchan Shukla has filed a ‘habeas corpus’ petition at the High Court of Madhya Pradesh and alleged that the National Security Act (NSA) invoked against her husband was politically influenced. On 17 July, the high court issued a notice to the state government seeking an explanation for invoking the NSA against Shukla.

Meanwhile, to ensure Ravat and his family’s safety, security personnel note down the details of every visitor in a register before allowing them to meet Ravat. He is not allowed to leave the house unescorted.

Also read: No one wants to talk about rapes in Manipur. There’s a silence at the heart of the violence

Setting political scores

Sudeep Kumar Diwedi, who lives a few houses away from Ravat, blames the recently concluded local elections for creating deep rifts among the villagers on caste lines. “During the elections in January, two camps were created within Pravesh’s extended family, each supporting different candidates. This video from 2020 was released to settle scores of the local body elections,” claims Diwedi. He also says that the three generations of Ravat’s family have been living on a plot of land given to them by Diwedi’s family.

Sidhi district falls in the Vidhya Region of Madhya Pradesh, which accounts for 30 assembly seats. During the 2018 assembly elections, the BJP swept the region winning 24 out of the 30 seats. The Congress won merely six seats. But four months ahead of the 2023 assembly election, the video showing Pravesh Shukla, an upper caste Brahmin, urinating on Ravat, a tribal man belonging to the Kol community, has brought these two communities at loggerheads. Brahmins, constituting only about 5 percent of the state’s population, are an influential community. Meanwhile, Kols dominate the Vindhya region and they have the third largest tribal population in Madhya Pradesh after Bhils and Gonds.

According to KP Rakesh, state president for MP Kol Adivasi Samaj Seva Sangh, the video resembles the treatment of the tribal community at the hands of the upper caste. “We held demonstrations in protest of the incident and even tried giving a memorandum to the collector, but when he did not come to receive it, we kept it at Baba Saheb Ambedkar’s foot,” says Rakesh.

The Congress party that held several demonstrations is all set to take out a Swabhiman Yatra from Sidhi raising their voice for tribal rights.

Back at Kubri market, Ravat along with the two policemen walks past a string of shops selling electronic items to medicines, looking for a place to eat samosas before returning home. He insists on going to Guru Gupta’s tea stall where he had been a regular for the past three years. On some days, he used to sit there chatting for hours. But today, he merely eats the samosas with his chai and heads back home.

At Ravat’s house in Karaundi, three labourers relentlessly work to raise a portion of the wall. Two patwaris sit on the charpoys in the open room of the under-construction house. With a newly-fitted table fan rotating nearby, they pour through the list of visitors written in the register.

Head constable Suresh Ravat has called in an agent from Sidhi to complete Ravat’s KYC.

After getting it done, Ravat sits in a corner scanning YouTube on his new android cell phone looking for the latest Bagheli songs. Asha, his wife, sits near him watching the walls of her house being built. Ravat’s interest in music is not new.

“In the old phone, I had a memory card with songs in them,” he says.

Also read: In Assam, trains prey on elephants. But Haati Mitras, AI have been defeating them for 4 yrs

What lies ahead

Ravat’s life has taken a drastic turn in the past few days.

About three years ago, he worked at a cement factory in Rajasthan and earned Rs 14,000 a month but since his return to Sidhi after his parent’s death, he has been working as a labourer to make Rs 300 a day and meeting ends for his family.

But today, his days are spent responding to queries raised by the administration and the reporters that come to meet him since the incident has come to light. He was given the new Android phone by the district administration.

“I do not get time during the day even to work on the house. It’s either officials or reporters that keep calling,” says Ravat. But he is unsure of what lies ahead of him once all of this settles down.

“If we stay alive then maybe we can think of putting up a flour mill,” he says. Listening to him, his wife retorts, “Now you can say whatever you wish, but you will stay a labourer.”

Much like Ravat, Asha is also hopeful a government job for Ravat will give them much-needed security and not leave them at the mercy of villagers for work.

“He has been working all his life as a labourer, but if he is given a job as a sweeper, we can live our life in peace where he will just go to work and come back home. One does not know what will happen in life next. We never anticipated something like this to happen, and so one cannot say how people will behave tomorrow,” says Asha.

Ravat also contemplates migrating to another state in search of a job if he is not given work in his village. After sitting briefly with Asha, he gets up and starts laying the bricks with other labourers.

He recollects something Guru had told him at the tea stall earlier in the day, “This life of yours is no good. When will you get Independence, will it be on 15 August, like the rest of the country?”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)