Hyderabad: A package containing a single toothbrush in a Ziploc bag arrives early one morning at Hyderabad’s Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology. Dr Karthikeyan Vasudevan opens it with mounting excitement. Hidden in this unremarkable object is the information needed to address a global poaching crisis.

The toothbrush, sent by a Kashmiri trader who deals in prized pashmina fabrics, contains microfibres collected from a shawl. Vasudevan’s team will analyse the DNA trapped in the bristles to determine whether it is pashmina wool or illegal shahtoosh made from the soft down hair of the near-threatened Tibetan antelope. Shahtoosh is difficult to identify, even in its raw form, and often gets woven with pashmina.

Now, the CCMB team has found a way to save the Tibetan antelope and the pashmina industry, globally valued at $1 billion in 2024, according to estimates by Verified Market Reports.

“The most common way to smuggle shahtoosh shawls is by labelling them as pashmina. The two are very difficult to distinguish with the naked eye,” said Dr Vinay Nandicoori, director of the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB). “It costs genuine pashmina weavers lakhs in losses as their products are caught up in customs on the basis of suspicions.”

After requests from Kashmiri traders and weavers alike, the CCMB team has come up with the world’s first DNA diagnostics technology to identify shahtoosh and pashmina shawls. The method is unique. Not only does it extract DNA from the shaft of a mammal’s hair—previously thought to be impossible—but it does so without damaging the expensive shawl. All it takes is for someone to rub a toothbrush on the cloth and trap the microfibres. This patented technology is now being offered by the CCMB lab in Hyderabad for a nominal fee, with plans to expand to a lab in Srinagar soon.

“This won’t just help global efforts to curb illegal shahtoosh trade, but also bolster the Indian pashmina industry,” said Vasudevan, who is Chief Scientist at CCMB. “With DNA testing, genuine pashmina weavers can be certified.

DNA on toothbrush

In late 2021, the Pashmina Exporters and Manufacturers Association approached Dr Karthikeyan Vasudevan with an existential crisis. His lab at CCMB specialises in disease and conservation ecology of endangered species. The traders were frustrated by the current methods of shahtoosh detection. The random seizures and prolonged checks at every stage were hurting their sales and exports worldwide.

The global crackdown on shahtoosh trade, which began decades ago in the 1980s, often meant that their pashmina products would be stopped multiple times at international airports and shipping yards. And due to these repeated customs issues, the value of pashmina exports from Kashmir suffered. It dropped from Rs 305 crore in 2018-19 to Rs 166 crore in 2021-22, according to the Kashmir handicrafts department.

“Pashmina weaving has been a centuries-old tradition in Kashmir, but more and more, the newer generations are straying away from it,” said Imran Rashid, general secretary of the Pashmina Exporters and Manufacturers Association in Kashmir. “They were saying there’s so much hassle, exports get stopped, there are so many losses. Why bother with it?”

There are ways to identify the difference between pashmina and shahtoosh, but they can be time–consuming. Under a microscope, pashmina fibres are minutely thicker than shahtoosh, and that is usually the metric used to tell the difference. However, traders complain that for customs and wildlife authorities to conduct these tests, it takes days, during which they suffer significant losses.

“I remember times when some exports get stopped on suspicion and are held for years together, while the authorities confirm whether it is pashmina or not,” said Rashid.

Given that the Tibetan antelope, commonly known as the chiru, is protected under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, or the CITES Act, Interpol is often involved as well.

“There are CBI raids in weavers’ houses and businesses, mainly in Kashmir. The pashmina testing centres are either in Delhi or Amritsar, which is quite far from where the weaving takes place,” said Vasudevan. “The industry was suffering, and we were asked to help.”

Vasudevan rose to the challenge with the logic and intuition of a scientist.

“We were given a simple problem statement—find a solution that’s foolproof, quick, and can be applied to anywhere in the pashmina supply chain. Whether we are given a piece of raw wool or a finished scarf, we should be able to tell whether it is the legal pashmina or the illegal shahtoosh.”

Most of the shahtoosh is not produced in India since Tibetan antelopes are mainly found and hunted in Tibet’s Changtang region, according to research by the Wildlife Protection Society of India. However, raw shahtoosh wool makes its way through the shared border with Tibet to to Kashmir and Ladakh, where the weaving centres are.

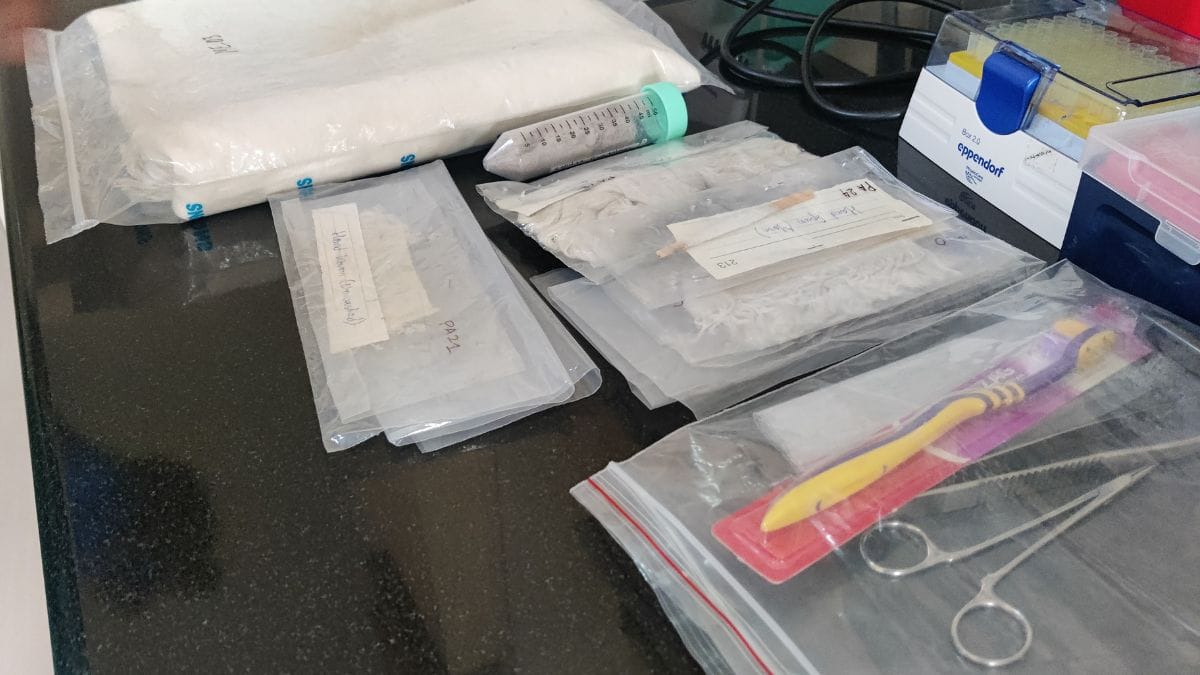

Pointing to bags of samples stacked in the laboratory, Segu Harika, senior technical officer in Vaudevan’s lab, said the goal was to simplify the process.

“Sometimes, officials confiscate tens and hundreds of shawls at once. Instead of having to send them all to us for sampling, which would be a tedious process, we thought, why not figure out a way in which we get the DNA from a few strands of fur and the actual shawl stays with the authorities,” Harika said.

Also read: Companies don’t want mid-career women. That’s a missing middle in corporate India

Hunting for DNA

A team of six researchers set to work in 2022 on the biggest challenge: how to extract workable DNA from pashmina wool without destroying it.

In his lab on the first floor of the CCMB’s Laboratory for the Conservation of Endangered Species (LaCONES) campus in Hyderabad, Vasudevan explained how both pashmina and shahtoosh wool is made from the shaft of the hair strand.

“For DNA fingerprinting for humans, you might have seen how hair is often used—that is because the root of the hair that connects to the scalp has millions of cells,” said Vaudevan. “But animal fur doesn’t usually have this root. It is just the shaft of the hair, which is mainly protein.”

Getting enough DNA to study and identify the species from the hair seemed difficult. Not only that, but the strand often goes through many stages of processing, including washing, dyeing, and weaving, before being made into a shawl, which is bound to fragment the DNA.

“Who would have thought that the pashmina scarf or shawl you wear has the DNA of the animal on it? It seemed impossible to whoever I told this to,” Vasudevan said.

However, the team figured out that while the shaft of the hair might not have nuclear DNA, which is preferred for analysis and identification, it did have mitochondrial DNA or mtDNA. However, while it is present more frequently in cells as compared to nuclear DNA, mtDNA still makes it difficult to uniquely identify the species of an animal.

“There are unique signatures in any animal’s DNA, which can help distinguish it from another,” said Harika. “The problem is, these signatures are readily available in DNA. We have to hunt far and wide in mitochondrial DNA.”

And hunt they did.

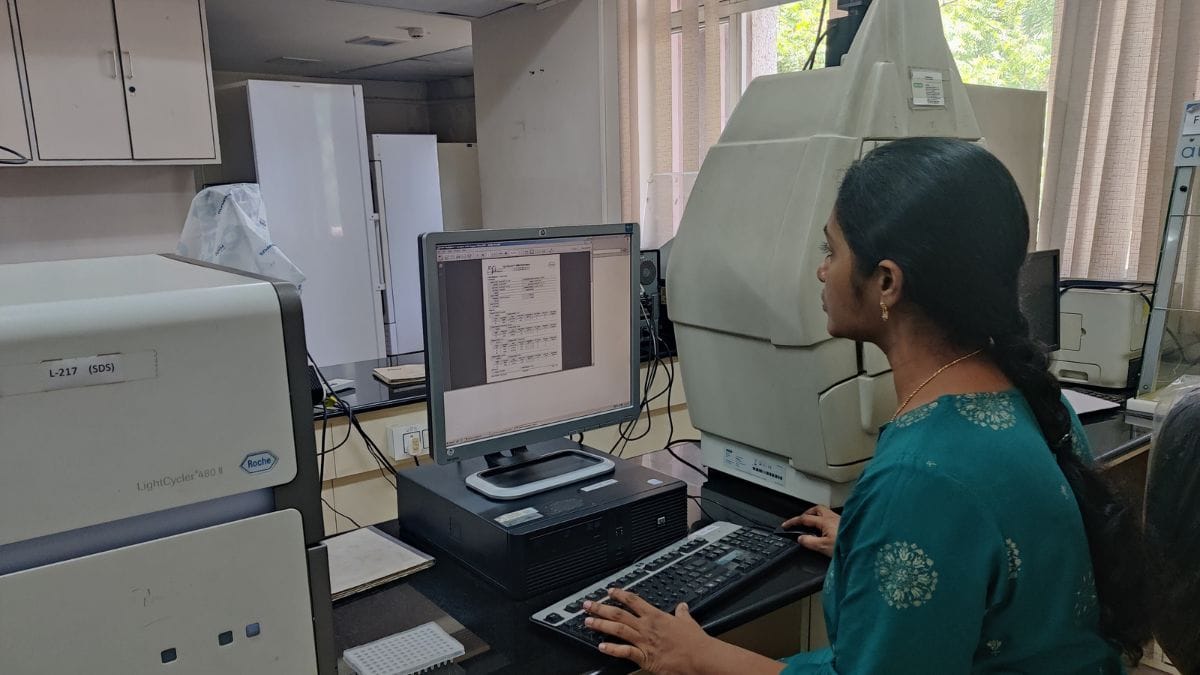

Within a year, the team at CCMB was able to identify a primer—a strand of the mitochondrial DNA—unique to the chiru species. Once this primer was identified, the process became simpler. All DNA from incoming samples is now matched with this chiru-specific primer.

“The interesting thing is that our primer is strong enough to detect even a few strands of chiru hair, so there’s no scope for false negatives,” Vasudevan said. “Also, to avoid false positives, we have tested it against many other DNA and materials to confirm that only chiru fabric will bind to it.”

Existing method

Shahtoosh loosely translates to ‘king of fabrics’ in Persian. It was worn by Mughal emperors and other royalty since the 15th century, and even now, there are relics in museums of wool shawls that turned out to be shahtoosh.

“Most of the fabric samples that we got for our testing were from museums—the Salar Jung in Hyderabad, even the Berlin museum [Staatliche Museen zu Berlin],” said Harika. “See, we needed shahtoosh samples to verify our study, but since they’re banned, even getting the fabric for scientific purposes was difficult.”

Harika recalled the multiple visits to Hyderabad’s Salar Jung Museum and calls to exporters, customs departments, and others with access to shahtoosh wool to ask for samples. In terms of customers, only those who inherited shahtoosh shawls from their family are allowed to hold onto their shawls, otherwise, they would have to turn them in to the wildlife authorities.

Despite the 1975 ban on shahtoosh wool under the CITES Act, products made from the material have been routinely seized internationally. The Indian government banned the trade in 1991.

Last year, according to a report by the Wildlife Trust of India, around 537 shahtoosh shawls, worth over €2.5 million, were seized by Swiss customs officials. One shawl, which takes the wool of up to 3-5 chirus to make, is sold for between €10,000 to €20,000 on the European market.

The way most authorities currently detect shahtoosh is by using a method known as light microscopy, using the standard light microscope available in labs everywhere. It relies on the morphological differences between shahtoosh and other wool, meaning the physical shape and features of the strands.

“Shahtoosh wool is the smallest in terms of microns, and it also has distinctive patterns on its fur—that is how we identify it,” said SK Gupta, the nodal officer of the Wildlife Institute of India’s Pashmina Identification Centre.

Established in 2023, the centre uses the microscopy method to identify shahtoosh and pashmina samples. According to Gupta, it is the most reliable method since others are prone to failures.

“We, at the Wildlife Institute of India, have been testing pashmina and shahtoosh samples using the morphological method because we know it is more reliable than DNA or other methods,” Gupta said. “Even internationally, in the US, they use microscopy. DNA doesn’t always work.”

He clarified that he isn’t against DNA analysis and that the Wildlife Institute of India uses it for many purposes that require it. But in the case of shahtoosh identification, given the quality of samples and range of wool fabrics used in production, DNA doesn’t always give the required results, he added.

Vasudevan doesn’t agree. According to him, DNA testing is a foolproof method, while microscopy still relies on a person examining each individual patch.

“The existing methods of identification are still prone to errors—in this case, these errors could cost someone their livelihood,” Vasudevan said. “If a genuine pashmina producer gets mistaken for producing shahtoosh, they could be entangled in legal matters for a lifetime.”

Also read: BrahminGenes Anuradha Tiwari has launched a war on caste census. ‘A betrayal by Modi govt’

From research to real world

In August 2024, Vasudevan’s team finally filed the patent for their unique shahtoosh identification strategy through DNA testing in India, Canada, the US, Europe, and the UAE. At the same time, they were also working on another DNA diagnostics technique that would be able to tell whether a sample is pure pashmina or mixed with merino and angora fabrics.

But the patent is not the culmination. Now comes the real job: making sure this technology reaches its potential.

“Right now, our DNA services are up and running as part of CCMB’s diagnostic services. Anyone can send us samples and receive results for the price of Rs 1035,” said Harika. “But given that most Pashmina weavers are in Kashmir, we wanted to establish a centre closer to [them].”

CCMB is in talks with the Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine, Srinagar to establish a DNA testing facility there so that it is accessible both to the manufacturers and the wildlife crime authorities. The team is also in talks with a few governments abroad, who want to use this new technology in their own systems.

“Science isn’t just for the lab—it is for everyone. It is to make a change in society,” Vasudevan said. “If we don’t see how our technology can actually be integrated into the industry and make an impact, then what was the point of this work?”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)