Noida: Tucked away in Noida’s Sadarpur in a narrow, traffic-clogged lane is the city’s best-kept secret—a dilapidated Mughal-era monument resting on its crumbling Lakhori bricks of a private property. Nobody can see it. The owner has erected a wall around it to shield this fragile piece of history from prying eyes.

“We didn’t want anyone to know about it. We didn’t want a religious dispute,” said Bharat, a 38-year-old mechanic. He lives in a two-storey house next to the monument with his wife, brother, and parents. The monument couldn’t stay hidden for long. An Instagram post by a history geek (@_citytales) outed it to the public in 2021. Another post in 2024 brought more attention to the monument.

Now, Bharat’s worst fears are unfolding. Historians and conservationists are knocking on his door. Citizens-turned-detectives are trespassing, hunting for ‘clues’. Hindu groups have started calling it a Shiva temple. And local Muslim residents insist it is a tomb.

But beyond all this din, the presence of this curious monument indicates the neglected histories of Noida—a city built 50 years ago as an industrial area with scant recorded memory or built heritage. The last remaining pieces of history don’t find any mention or commemoration on brochures or websites. Instead, the Delhi suburb is mostly busy showcasing its latest high-rise or swanky shopping complexes. The only architecture in Noida that is talked about is the mall. Nobody will tell you about the city’s history.

The Noida region was part of the Mughal empire for centuries. It was where Delhi’s enemies could attack—from the periphery. It’s where the British fought the Marathas. And it was Bhagat Singh’s hideout as he plotted against the colonisers.

“Historically, Delhi has been the centre of power; the Mughals or the British focused on protecting and developing the city. The other side of Yamuna bank was never anyone’s priority unless an attack came from that side,” said Vijay Seth, a writer, aviation historian, and author.

Bhagat Singh’s hideout

“The Yamuna did not have many bridges, so it was not easy for the British in Delhi to cross the river to catch him,” said Major General (retd) Sheonan Singh, Bhagat Singh’s nephew.

Before the idea of Noida took shape in 1976, much of it was wetland and marshy areas because of its proximity to the Yamuna, along with patches of forest. It proved to be an ideal place for freedom fighters like Bhagat Singh and the Indian National Army to take cover.

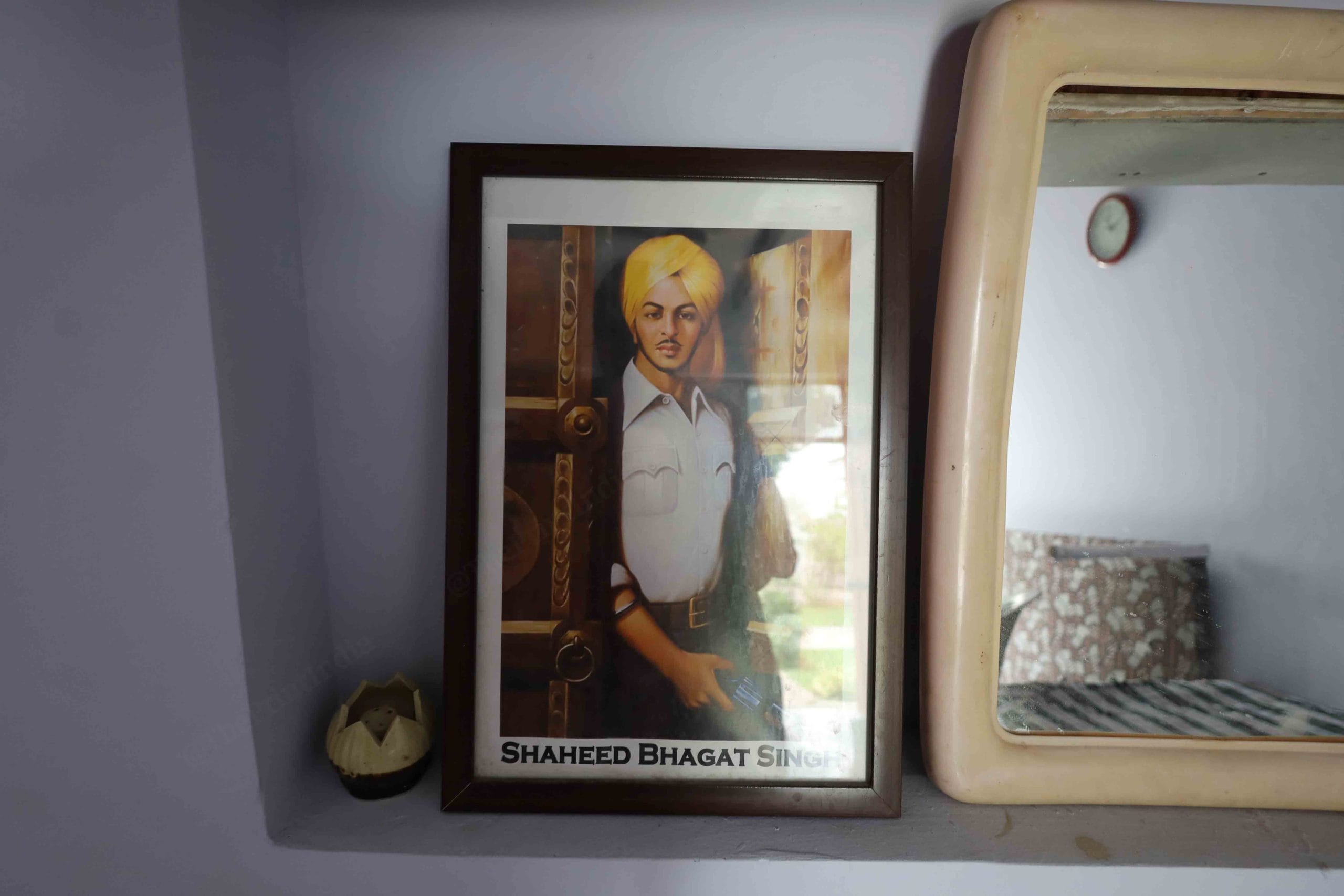

Among his descendants, his exploits have been passed down from generation to generation as part of family lore. Singh fled from Kanpur around 1924 and came to Noida, where he ended up working as a primary school teacher in a village, according to the freedom fighter’s nephew, Major General (retd) Sheonan Singh, who now lives in Greater Noida. Members of the revolutionary party, Hindustan Republican Association (HRA)—where Bhagat Singh held a prominent position—would come to meet him.

“This area was a safe hiding place, not far from Delhi. In those days, the Yamuna did not have many bridges, so it was not easy for the British in Delhi to cross the river to catch him,” said Sheonan Singh.

Over the years, the stories of Bhagat Singh have taken on a life of their own. At Nalgarh village in Noida, residents insist that he lived with them. A left turn from the busy Noida-Greater Noida Expressway leads to the village where a gurudwara stands as a sentinel of its history. Within the premises, a massive rock is displayed on a platform.

“This was the rock that Bhagat Singh used to make a bomb,” said a woman in the gurudwara. She was busy arranging the langar along with eight to 10 women in a large room where a photo of the freedom fighter was proudly displayed along with the Sikh gurus.

In April 1929, Bhagat Singh, along with freedom fighter Batukeshwar Dutt, planted two low-intensity bombs at the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi. They were arrested for the incident, but during the investigation, the authorities linked Singh to the murder of John Saunders, a British police officer. The freedom fighter was only 23 years old when he was hanged in 1931. By then, he had become a symbol of India’s fight for freedom.

India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in Toward Freedom devoted a chapter to the martyrdom of Bhagat Singh. “Within a few months [of his death] each town and village of the Punjab, and to a lesser extent in the rest of northern India, resounded with his name.”

And it continues to do so in the Nalgarh. Children of the village grow up on stories of Bhagat Singh and the Indian National Army. “He experimented with the bomb in our village field. Sukhdev Thapar would come here to meet him,” a villager said.

The rock placed in the Noida gurudwara and its link to Bhagat Singh and India’s fight for independence is a badge of honour for the villagers, most of whom fled Pakistan after Partition. One of the residents, Jaspal Singh, while distributing flavoured milk to motorists on the highway, pointed to a paddy field.

“We found it there,” he said. “For many years, it was kept at someone’s house, but around five years ago, we shifted it to the gurudwara for its safety.” Today, a few families light incense near the stone.

“Bhagat Singh used to travel a lot, that is for certain. But there is no clear-cut picture of where he stayed, the duration, or even records of his activities,” said Chaman Lal, honorary advisor of the Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, Delhi.

In 2015, the Noida Authority invited architects to come up with suggestions for a Bhagat Singh memorial at Nalagarh. Anand Mohan, Director of Noida Authority’s Horticulture, told ThePrint that the land for the memorial was allotted a long time ago. “We are working on developing a park and memorial on the land,” he said.

Chaman Lal, Former JNU professor and honorary advisor of the Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, Delhi, takes the village lore with a pinch of salt. “The local people have created folktales,” he said, adding that there is no historic record of the stone-bomb connection.

“Bhagat Singh has become a legend all over the country, especially in north India. He used to travel a lot, that is for certain. But there is no clear-cut picture of where he stayed, the duration, or even records of his activities,” said Lal.

Even Bhagat Singh’s nephew cannot confirm whether the stone was used to help in the making of a bomb. “I am not sure if a bomb was made or not. Bhagat Singh and party members may have tested a low-grade bomb on the rock. But that is just an assumption,” he said.

During the freedom struggle movement, there are traces of Bhagat Singh in what is now Greater Noida as well. With the British on the lookout for him, he was always on the run. He hid his identity and kept a low profile.

“In Jewar, there is a village where Bhagat Singh came and taught in a school. It was for a short while, but you have schools named after him there,” said S. Irfan Habib, a historian.

But the lore around Bhagat Singh and the bomb is now firmly embedded in Noida’s history. It even finds mention in the Culture and Heritage section of the Noida Authority’s website.

“In the Nalgarh village on the edge of Noida, Greater Noida Expressway, Bhagat Singh conducted several bomb tests while underground. Even today, there is a huge stone kept safe.”

Also read: The idea of Noida. The bad boy of NCR, Mall of India swag, a culture vacuum

City that was a battlefield

More than a hundred years before Bhagat Singh was hanged, Noida was the site of one of the battles in the Second Anglo-Maratha War. A stone pillar in the putting greens of Noida Golf Course in Sector 37 marks this chapter in the city’s history.

Called the Victory Pillar, it’s a memorial to the Battle of Delhi or the Battle of Patparganj, which took place on 11 September 1803. At the time, Noida was a cluster of villages, one of which was Patparganj. It still exists as one of the localities on the other side of the Yamuna. The village was considered to be the periphery of Delhi, from where enemies always attacked.

That’s what happened on the battle day. On one side was the East India Company, its troops led by British general Gerard Lake. On the other side was the Maratha king Daulat Rao Scindia’s army under French commander M Louis Bourquian. Scindia was defeated, and Delhi fell under the control of the East India Company, tilting the axis of power in north India.

Jyoti Ogra, an INTACH member, told ThePrint that the memorial is known as the “Pillar in the Golfing Greens”, a name suggestive of its location. But it was built only another 100 years later, when Lord Curzon, who served as the Viceroy of India from 1989 to 1905, was holding the Delhi Darbar in 1903. It was when he decided to commemorate the soldiers who died in the battle. But it soon faded from public memory and remained forgotten in Noida’s wetlands and forests.

Cut to 1989. It was the Noida Authority that restored the Victory Pillar. The inscription of the event can now be read clearly: “Near this spot was fought on September 11, 1803 the Battle of Delhi in which forces of the Marathas, commanded by M Louis, were defeated by the British Army under General Gerard Lake.”

Today, club members gaze at the pillar near hole number 7 as they roll by in their golf carts. But few young people know its significance. Older members keep the memory alive.

“There are no signboards there to tell golfers or visitors of the pillar’s historic significance,” said retired Colonel Virendra Sahai Verma.

Local residents call it the ‘Jeetgarh Stambh’. “We have seen this for years now, many foreigners come here looking for the pillar,” said Babulal, an employee at the club. He calls the pillar “Makbara”, a tomb.

Noida Golf Course, a private property founded in 1989, is surrounded by residences. It is in one of the prime locations of the city. Only members and their guests are allowed to enter the property. Hence, the pillar is not protected by the Archaeological Survey of India.

“The battle was fought near Patparganj, it was near the river, it was not fought at the memorial site, but close to the Yamuna river. After 100 years, someone must have told Lord Curzon during the Delhi Durbar about the two British officers who were buried at the location, and he must have thought of commemorating them, hence the memorial was built there,” said retired Squadron Leader with the Indian Air Force Rana Tej Pratap Singh Chhina, a writer, and a military historian.

Some of the early settlers in Noida were the Gurjars, who made the floodplains their home. And a cluster of villages was born. Noida’s proximity to Delhi, where battles for supremacy are fought, has shaped its past and informed the present. But it was the villages that became the cornerstone of the city as we know it today.

“Noida’s history is marked by the combined history of several such villages that are inhabited by the Gurjar community, who trace their origin from the Rajput Gurjar Pratihara dynasty. Many of the Gurjar chieftains and villages have contributed to India’s freedom struggle. The villagers had provided their armies to the Mughal officials, maybe Subedars, who visited these villages,” said Neeta Dubey, member of INTACH Noida chapter, desk project manager of IIT Bombay’s National Virtual Libraries of India.

Ruins of Mughal architecture

“In the 18th century, tombs and shrines were built similarly, with just a little difference in the shape of the Chhatri or the canopy. It might have been a Shiv temple,” said Sam Dalrymple.

Today, most of the sprawling residential complexes have been planned and developed around the original villages. As Noida moved to the beat of development, the villages morphed into small localities but clung to their roots.

“Every sector of Noida has the name of a village with it,” said Ogra.

One such colony that is still untouched by development is Sadarpur. Here, the roads are narrow and congested. Electric rickshaws and motorbikes zip through as pedestrians bargain loudly with shopkeepers. There are no high-rises in sight. Instead, the lanes are lined with old independent houses that were probably built years ago. The streets, unlike the polished boulevards a few blocks away, are uneven, bumpy, and littered.

But the sun is dimmed by the looming presence of high-rise residential complexes like Godrej Woods and Ashray House Noida.

“In the map, the streets in the area (Sadarpur) have criss-cross lines, but if you see the other side of the map, the streets look planned in a linear line. It means they built Noida around these villages. When the density increases in an area, those are old villages, and on the other side, it’s the Noida we know today,” said historian and author Swapna Liddle.

The main road in Sadarpur is home to the Mughal-era monument in Bharat’s family compound. It’s hidden behind the facade of a new brick wall. The dome on top of the monument is partially covered by a Banyan tree.

“In the map of the area, the structure looks like it was constructed inside a village,” said Liddle. Bharat, who did not want his last name mentioned, is reticent about the monument.

“My family has been hiding this for very long time from the eyes of the world. We do not want anyone to know about this, we are already facing a lot of problems because of this monument,” he said.

He was in a hurry to get to work and refused to be photographed. “I don’t want trouble,” he said. He remembers the Meerut riots of 1987 when his father fractured his hand protecting the structure from rioters. The effects of the Meerut riots had spread to this part of Uttar Pradesh too.

A few Instagram posts from last year are among traces of its recent discovery—when a photographer, on a morning walk, stumbled upon it.

Bharat’s family claims that their forefathers bought this piece of land from a Sayyid family, when they were leaving the area. The monument has always been there. Now that the word has spread, everyone has an opinion. Muslim neighbours say it’s a mausoleum. Local Hindu residents insist it’s a temple.

“Ye toh humara Shiv Mandir hai (This is our Shiv temple),” local people say. As the family has barred entry inside their property, they’ve lit diyas, incense and candles on top of the brick wall.

According to historian and author Sam Dalrymple, the structure could be a tomb or a shrine.

“But it’s unlikely to be a sarai; it could always be a part of a larger complex,” he said. Sarais are Mughal-era rest stops akin to modern-day inns and hotels with elaborate courtyards and chambers. “But this is just a single structure. In the 18th century, tombs and shrines were built similarly, with just a little difference in the shape of the Chhatri or the canopy. It might have been a Shiv temple,” Dalrymple said.

For Shah Umair, a numismatist and historian who organises heritage walks in the city, the red Lakhori bricks indicate that the tomb dates back to the time of Shahjahan or later. And like Dalrymple, he doesn’t think it’s a sarai. Besides, Noida was not on any ancient route used by travellers.

The history of Mughal architecture in this area is hard to trace—there’s little material to go by, and the local people are hesitant to share their side of the story.

“This would have been countryside, this would have been the heart of a village. And there would have been a local subedar, a local tax collector, who would oversee these areas, it is difficult to know without more research, but the way these areas worked, it must have been a part of Delhi Subah,” said Darlymple.

The monument first came to notice in 2021, when a famous social media page, City Tales, run by Rameen Khan, posted pictures of the monument. Rameen Khan, who calls himself a history geek, wrote in the post, “Noida – a city in existence not even for half a century is not expected to have heritage. However, it incorporates in its multiple sectors, behind humongous multi-storeys, some medieval villages.”

“One of these is Sadarpur and it probably holds the last monument of Noida. For in its vicinity lies a Mughal era tomb which is in a terrible state today.”

Three years later, Hemant Arya, a history enthusiast, also found the monument. “On a chilly December morning, while exploring Sadarpur in Sector 45, Noida, I stumbled upon an old monument tucked away in the midst of urban chaos,” he wrote on social media.

With all the attention following the monument’s ‘discovery’, Bharat and his family would rather see it crumble to the ground.

“The structure keeps on breaking every year, little by little. An NGO has extended a hand to repair this tomb, but we do not want any publicity. Let this diminish slowly, with this, the dispute will also end,” said Bharat.

This article is part of a series called ‘Noida@50’. Read all articles here

(Edited by Ratan Priya)