New Delhi: By when do you see this becoming a Rs 1,000-crore company?

The question came almost reflexively from a VC investor, halfway through a pitch meeting. It was a standard prompt, but for 27-year-old Debabrata Basak, operating from a small 6-seater cabin at 91Springboard in Vikhroli, it was completely out of syllabus. It was 2024, and for founders of Indian AI startups like him, the old stock answers simply couldn’t be given.

In that room, two different mindsets were colliding, recounted Basak, co-founder and chief customer officer of GreyLabs AI, a Mumbai-based startup building agentic voice AI for banks and insurance firms. On one side were VCs trained to model scale early. On the other were founders still learning what “scale” even meant in artificial intelligence.

“We can’t really predict the addressable market here. That’s a leap of faith investors have to take,” Basak said.

GreyLabs AI found investors willing to do just that. In May 2024, it raised $1.5 million in a seed round led by Z47 (then Matrix Partners India). Last October, they secured another $10 million in a recent Series A round led by Elevation Capital, along with participation from Z47 and angel investors.

This captures a fundamental reset. A small but growing cohort of frontier-minded VCs is now bankrolling India’s AI boom. They are moving away from the comfort of the familiar software-as-a-service (SaaS) model. For decades, the question of how big, how fast, and how predictably a company could grow has anchored venture capital decision-making. But now, AI startups have disrupted the old rules. Several VCs are taking up the challenge by putting their money into nebulous timelines and markets that are often undefined. They are now spending less time interrogating five-year revenue projections and more time examining customer behaviour.

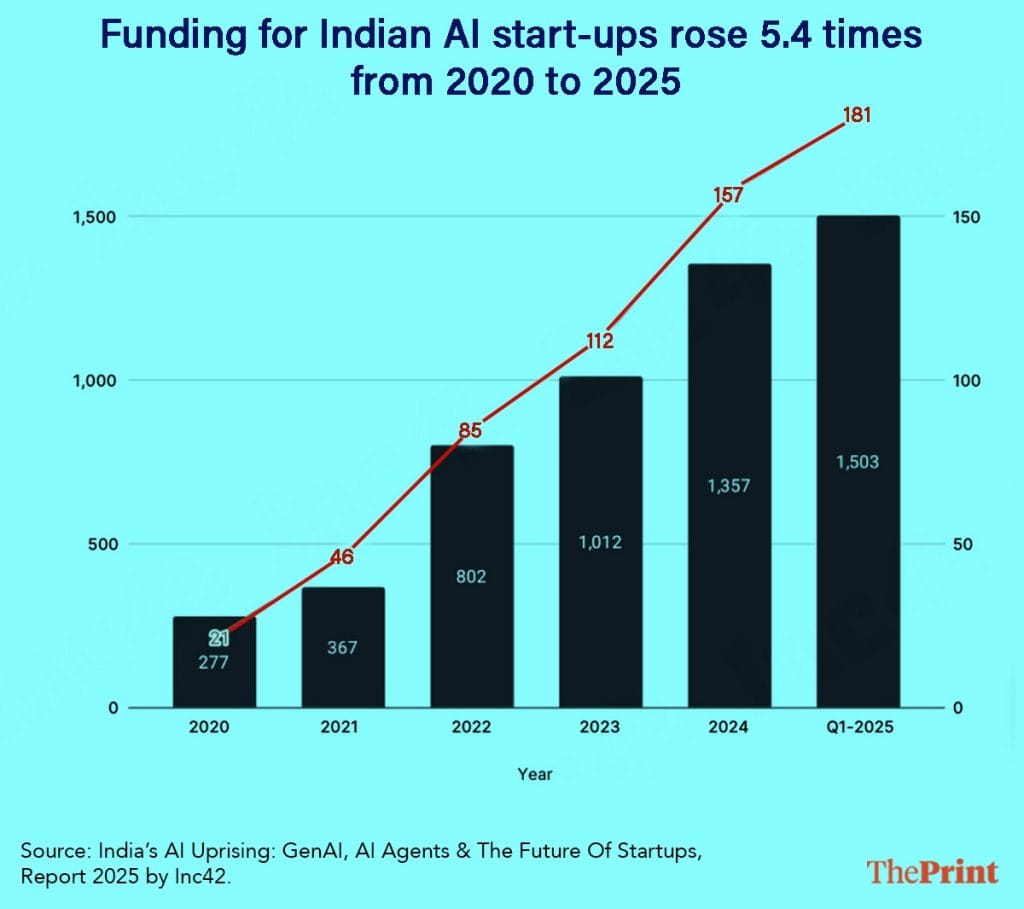

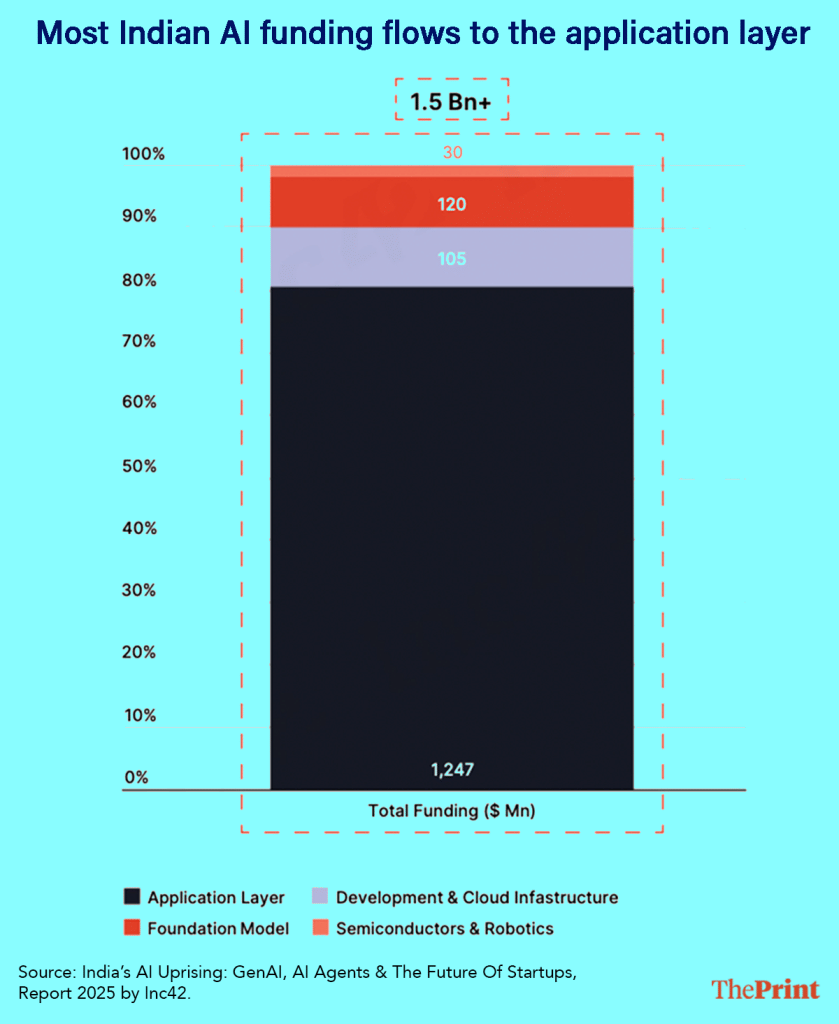

There are currently over 1,900 AI startups in India, including 555 that have raised $4.98 billion in VC money and private equity, according to market intelligence platform Tracxn. In just the period between 2020 and 2025, Indian AI startups raised over $1.8 billion, with the bulk of capital, 86 per cent, flowing into companies building applications, as opposed to foundational models or infrastructure. Nearly 70 per cent of these startups are still at the seed stage.

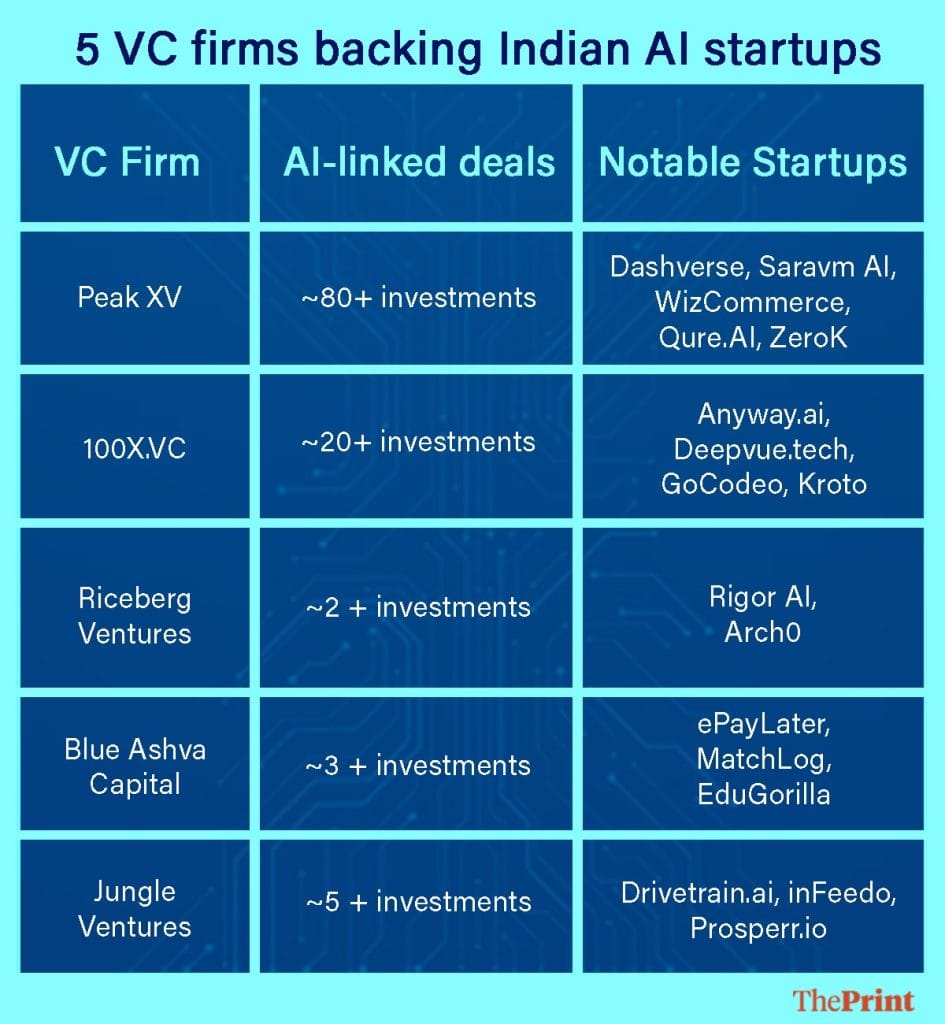

Some VCs make a distinction between ‘AI-native’ companies, built around the technology from day one, and firms that simply bolt AI onto older products. Ninad Karpe, a partner at 100X.VC warns about “wrappers”, or companies that put a thin AI feature on top of existing tools without adding much value. Others say the label matters less than whether the tool solves a real problem.

Arpit Beri, the Bengaluru-based managing partner at Jungle Ventures, belongs firmly to the latter camp. In his late thirties, he has spent over a decade investing in early- and growth-stage companies across consumer, SaaS and fintech.

SaaS scaled in a fairly predictable way. AI does not. It scales chaotically, with cost curves shifting weekly instead of yearly

-Ninad Karpe, partner at 100X.VC

“We don’t think in terms of AI-native versus AI-enabled. AI itself is not the investment thesis,” said Beri, whose firm’s Indian AI investments include drivetrain.ai (business forecasting), inFeedo (employee analytics), and Prosperr.io (tax management). “We always start with the customer lens.”

Such startups are also where India’s AI boom is concentrated. Rather than building giant Silicon Valley-style models, many startups are focusing on enterprise AI – tools for sectors such as banking, insurance, manufacturing, healthcare, education, and agriculture. This sector is expected to grow from $11 billion in 2025 to $71 billion by 2030, according to the Bharat AI Startups Report 2026. Consumer AI—which covers the gamut of personalised tools such as health apps and AI secretaries — is projected to expand from $13 billion to $55 billion.

For GreyLabs, the customer lens paid off early. One of its first clients, RBL Bank, agreed to pay for a three-month pilot, using the startup’s AI to automate call auditing. That willingness to pay, despite the product still taking shape, became a signal to VCs.

The VC firm did not concern itself excessively with “architectural novelty or model sophistication,” said Basak, an engineer and IIM Shillong graduate who has spent much of his career translating technology into customer outcomes.

“It can’t just be a fancy piece of tech,” he said. “It has to produce some ground-level value.”

That lesson resonates across India’s AI startup ecosystem.

Also Read: Who are the kings of India’s billion-dollar KYC industry? Identity is big business

‘Customer love’ in the age of AI

When 40-year-old Achintya Gupta, CEO & co-founder of Bengaluru-based Reo.Dev, went looking for funding, he led with “customer love”.

The company, which uses AI to help developer-focused companies figure out who is actually in need for a product like theirs, raised a $1.2 million pre-seed round in February 2024. Last October, it followed this with a $4 million seed round, led by Heavybit, with participation from Foster Ventures and India Quotient.

“A lot of conviction happened through our customers,” said Gupta, an IIT Delhi and ISB alumnus who is now based in California. “Our investor, while doing diligence, spoke to our customers. And those customers were genuinely crazy about the product. Nobody wants to invest where there isn’t enough customer love.”

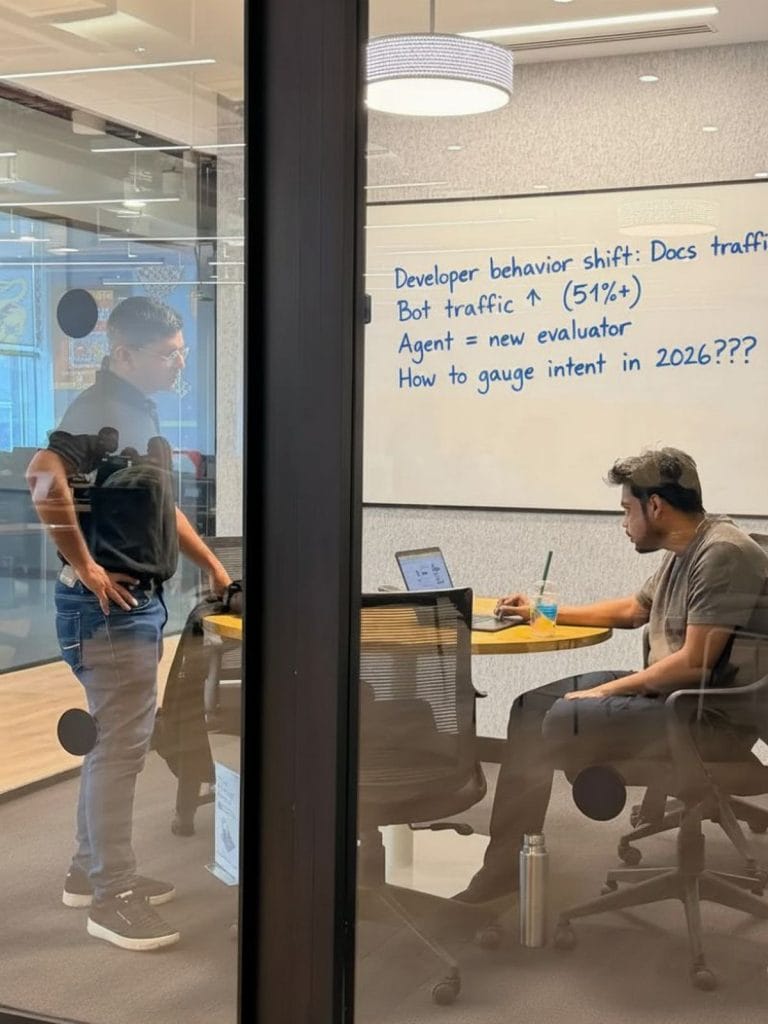

The idea for Reo.Dev grew out of his time as chief revenue officer at API platform Phyllo, where struggling to sell to developers pushed him to turn a personal pain point into a product. Founded in 2023, the startup uses AI to analyse developer activity across GitHub and other platforms to identify purchase intent.

Gurugram-based SpeakX, an AI-powered edtech platform, also priorised usage metrics while raising capital. In October 2025, it raised $16 million in a funding round led by WestBridge Capital, taking its post-money valuation to $66 million.

“Engagement and retention are the two core metrics which VCs are looking at with AI startups,” said Arpit Mittal, CEO and co-founder of SpeakX. “It’s not the growth and acquisition. What will happen when another business comes up with the same or similar solution? What is the reason that customers will stick with you?”

We look at how attractive the market is, the position a company can create, and whether AI enables faster growth or better profitability. Nobody is investing just for the sake of being supported by AI

-Raghav Bhatnagar, vice-president of Quadria Capital

In AI-driven SaaS, investors have become obsessed with “stickiness”— do customers keep coming back, and whether the product becomes part of their daily workflow.

That has produced a new vocabulary of metrics: onboarding velocity, time-to-value, feature adoption, API-call intensity, upsell velocity.

When these metrics align with robust margins and a favourable customer acquisition cost (CAC) payback, the investment case strengthens.

It’s more important in AI than other kinds of SaaS because the technology changes so fast and today’s edge can be infra-dig tomorrow.

“If it’s scalable but not profitable, that’s a problem. If it’s profitable but not scalable, that’s also a problem,” said Beri. “We have to make that judgment call today, and it goes back to how large the customer problem really is.”

What complicates that judgment in AI is that the cost structure itself is unsettled. In traditional software, once a product is built, the marginal cost of serving an extra user is low. In AI, every query comes with an ‘inference cost’: computing power, tokens processed, cloud bills. Customer acquisition costs, too, are unstable, shaped by how many competitors rush into the same narrowly defined use case.

Founders and investors are effectively underwriting two uncertainties at once: demand, and cost. Many expect servicing costs to fall over time as more providers enter the market and open-source models improve.

This is where India’s AI story begins to diverge from the American one.

“Building the next large language model requires billions of dollars, and India’s capital markets are nowhere near deep enough to sustain that bet,” said Beri.

What are Indian VCs looking for?

Raghav Bhatnagar of Quadria Capital points out a hard reality. India isn’t winning the race to build the next ChatGPT or Grok. While investors in the US and Europe put millions into creating primary AI models—the “building blocks” of the technology—India VCs are taking a more practical approach.

“What is happening in the US and Europe is more transformative. In India, while construction is happening, innovation around foundational frameworks remains limited,” said Bhatnagar.

Where he sees meaningful opportunity is in applied use cases, such as in healthcare or fintech. The verticals seeing real traction are those with task-specific agents, penetration testing tools, debugging systems, memo-generation engines and other applications where customers are actually paying.

“We look at how attractive the market is, the position a company can create, and whether AI enables faster growth or better profitability,” he said. “Nobody is investing just for the sake of being supported by AI.”

Innovation alone doesn’t impress investors anymore. What matters more is ‘defensibility’, or whether a startup has built something competitors can’t easily replicate.

“Building primarily on the application layer is not a weakness, it is pragmatic,” said Ninad Karpe, a 66-year-old Mumbai-based partner at 100X.VC and the former CEO of Aptech. “The real danger lies in mistaking wrappers for businesses, and confusing early traction with defensibility.”

Last year, 100X.VC emerged as one of the most active early-stage AI investors in 2025, backing 11 startups including AnywayAI, Whiteable AI, Datavio, and GoCodeo in deals worth about Rs 14 crore.

When there is a gold rush, you sell the shovel

-Ankit Anand, founding partner, Riceberg Ventures

As startups progress toward later funding rounds, the requirements become tighter. At seed stage, Peak XV’s focuses on partnering with world-class founders building in large markets. At the venture stage, it looks for those elements along with early product-market fit.

“The math has to work at the growth stage, and we need to see a strong economic engine,” said Rajan Anandan, managing director of Peak XV.

When it doesn’t, capital pulls back. The biggest risk, Beri warned, is when valuations sprint ahead of business fundamentals and founders begin optimising for funding rather than customers. He gets wary when exciting stories, bold visions, or trendy narratives take over, creating the conditions for a bubble-and-bust cycle.

“When imagination catches attention, markets swing from one extreme to another,” he said.

Placing the bets

To land deals in an increasingly crowded AI market, venture capitalists are no longer waiting for founders to come to them. They are moving earlier, faster, and farther afield.

GreyLabs, for instance, did not actively pitch to investors. The startup was ‘discovered’ through word of mouth. Basak said Axis Bank, an early customer, was impressed enough by GreyLabs’ voice AI and speech analytics that word of its work travelled to Elevation Capital. Today, GreyLabs AI serves 50+ leading BFSI enterprises in India.

Ankit Anand, managing partner at Riceberg Ventures, said they spend little time on pitch decks, focusing instead on the story of how and why a founder is building. The firm stays close to the ecosystems where products are being built, relying on networks and on-ground presence to surface companies before they formally raise capital.

Some big funds are creating their own startup pipelines as well. Peak XV’s Surge program, for instance, is a dedicated platform where founders can apply before traditional fundraising, allowing investors to spot promising AI startups before the market does.

When it comes to deciding where to place the chips, VCs have their own preferences and strategies.

Peak XV calls their approach “full-stack AI,” which is essentially a bet on every layer of the technology. Their investments range from Truefoundry, an AI deployment and scaling platform, to Atlan, which specialises in data governance.

First, said Anandan, they track companies that work on the architecture and ‘plumbing’ around AI databases, data infrastructure, developer and agent tools, AI gateways, and security, as well as teams trying to build foundational models in India.

The second category is enterprise AI—especially agentic platforms focused on functions such as marketing, sales, customer support, finance, HR and product management—and the third is consumer AI.

“We closed our 80th AI investment in late December 2025,” added Anandan.

Macro investors can underwrite foundational bets at scale. Micro investors can’t— real risk emerges when capital, ambition, and strategy are misaligned. In AI investing, clarity of position matters as much as conviction

-Satayam Goyal, investment manager, Blue Ashva Capital

By contrast, others are narrowing their aperture.

At Riceberg Ventures, a global VC fund with offices in San Francisco, London, Zurich, and Bangalore, the emphasis is less on end-user applications and more on the infrastructure that makes AI possible.

“When there is a gold rush, you sell the shovel,” said Ankit Anand, founding partner of Riceberg Ventures, alluding to how the most reliable fortunes in the California Gold Rush were made by merchants who sold the tools rather than those digging. In the AI era, he pointed to chip giant NVIDIA as the ultimate success story, which became the world’s first $5 trillion company last October.

But rather than trying to build another NVIDIA, Riceberg searches for startups tackling overlooked problems, including how to organise massive computing power, secure infrastructure, and optimise costs. It also prioritises companies building for global markets.

The firm is tracking long-horizon bets in quantum computing and unconventional data centre architectures, including experimental projects involving inflatable solar habitats designed to host compute infrastructure. Another new frontier is AI-driven cybersecurity.

“If there are maybe a thousand people globally who understand foundational AI, imagine how few also understand cybersecurity,” said Ankit Anand. The overlap is vanishingly small, and therefore potentially valuable.

Some VCs are taking an even more panoramic view. Blue Ashva Capital is most interested in “second-order effects”, the ripples AI creates across the entire economy.

“AI doesn’t just create new products, it reshapes how work itself is valued,” said Satayam Goyal, an investment manager at the firm.

From this perspective, investing is less about predicting which AI product will win and more about understanding how the technology reconfigures the system.

“Macro investors can underwrite foundational bets at scale. Micro investors can’t— real risk emerges when capital, ambition, and strategy are misaligned,” said Goyal. “In AI investing, clarity of position matters as much as conviction.”

Across these different approaches, most investors acknowledge a sobering reality: a good AI model is not a ‘moat’ that protects a business from competitors.

“That’s an uncomfortable truth many founders avoid,” said Karpe. “If a large technology company can replicate a product in a single release cycle, what was built was never defensible. It was merely a feature waiting to be copied.”

The real moats, he argued, come from strengths that are harder to copy, whether it’s a solid distribution network or proprietary data.

AI chaos, longer T&Cs

For nearly two decades, venture capital in software hinged on a simple, comforting scoreboard: Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR). If a startup could show a steady and speedy growth in subscriptions, VCs got a sense of security and jumped in. That logic, however, is beginning to fray.

“SaaS scaled in a fairly predictable way,” said Karpe. “AI does not. It scales chaotically, with cost curves shifting weekly instead of yearly.”

In AI, revenue is often usage-based rather than fixed. An AI writing assistant used by a company, for instance, might cost one customer $500 in a light month, while another that uses it far more heavily in the same period pays $5,000. Both may value the product equally, but traditional ARR struggles to capture that variability.

Traditional valuation methods offer little guidance when revenue and costs are constantly changing… How do you actually decide anything when everything is in flux?

-Ketan Mukhija, co-head of the VC practice at Kochhar & Co

For an investor, this makes it much harder to tell the difference between a temporary surge and a real, growing business.

As a result, investors are turning to hybrid valuation models that focus less on the size of a subscription base and more on whether the AI tool delivers measurable, repeatable outcomes. In this cycle, advantage lies less in how fast a company sells and more in how quickly it adapts and responds to real-world use.

The loyalty of customers, too, has become more fragile.

In the past, companies found it difficult and expensive to switch software providers once they had integrated a service into their operations. This ‘lock-in’ effect provided startups with a durable competitive advantage.

AI models, by contrast, can quickly ingest data from emails, documents, and databases, lowering barriers for customers to switch providers. A startup may reach a few million dollars in ARR only to be displaced by a competitor with a marginally better model or feature. The central question for investors is no longer whether a product works, but whether it can endure, said Karpe.

The third shift shows up in deal structures.

“In AI funding, the first point of friction is almost always price,” said Ketan Mukhija, co-head of the VC practice at Kochhar & Co, who advises investors and founders on structuring funding rounds. “Traditional valuation methods offer little guidance when revenue and costs are constantly changing.”

For example, Net Present Value (NPV) calculates today’s value of future cash flows, while Terminal Value estimates what a company might be worth at the end of a forecast period, assuming steady growth.

“How do you actually decide anything when everything is in flux?” he asked.

To manage these uncertainties, Mukhija explained, venture capital firms in India are rewriting deal terms to protect themselves and maintain more control. Earlier clauses, such as 1x non-participating liquidation preferences, guaranteed only that investors would recoup their original investment if the company was sold. Today, participating preferences allow investors to recover their investment and take a share of remaining proceeds. Some deals now come with minimum-return protections, while milestone-linked funding releases capital only when the startup meets specific targets.

AI has also brought a new layer of safeguards. Investors are seeking stricter commitments on intellectual property, limits on using open-source or third-party training data, and restrictions on founders reusing models after exit.

They are also pushing for earlier board involvement and tighter rules to keep key AI engineers and founders in place. Milestones are tied not just to revenue but to model performance and cloud costs, with future funding being released only if the startup hits measurable targets.

“It is not an area where people would end up deploying endless capital without a clear visibility on the ROI,” added Bhatnagar from Quadria Capital.

Why teams matter more than ever

In the volatile world of AI, the human factor has become even more important to VCs. A strong founding team with complementary strengths is high on the checklist.

At Riceberg, resilience is a particularly valued trait. For Ankit Anand, what matters most is a founder’s ability to survive repeated resets of the model, the pricing, the customer, and sometimes even the company itself.

“The founders who stand out are often crazy about the technology in the best sense,” he said. Those are the ones who are most likely to be unfazed by macro cycles or hype while they grind through the long, uncertain journey.

In Mumbai, GreyLabs, founded in 2023, has no fewer than six co-founders. While CEO Aman Goel and CPTO Harshita Srivastava are both IIT graduates and drive the product and technology front, Shreyas Patel, Shivam Gupta, Raj Sanghavi, and Debabrata Basak lend their expertise in AI engineering, go-to-market execution, and business operations.

Basak insists his engineers practice what he calls “forward deployment”, which means working directly with customers to do prompt engineering, tailor models to their needs, and integrate models into their daily workflows.

GreyLabs also made an unconventional choice to hire senior leadership before scaling junior teams, betting on a top-down structure to manage complexity and accelerate learning. After its Series A, Basak said the organisation had to reset structurally and formalise roles to avoid the internal friction that often emerges as startups grow.

In AI startups, where investors often back teams as much as products, keeping founders and key engineers in place through critical milestones is increasingly non-negotiable. It’s a measure of stability in a landscape of perennial flux.

“At a leadership level, we did have clauses to extend lock-ins,” Basak said. “Constant resetting has become a feature. As a founder today, you have to question your thesis almost every month. The pace of change leaves little room for long planning cycles. Things are changing so fast that building fast is the only mode.”

India’s asymmetric advantage

If there’s one thing that investors and founders can agree on, it’s that AI will not compound for everyone.

‘Infra-first’ founders are already staring at commoditisation, where unique software stack gets copied and sold for a cheaper price, according to Basak.

“This is why investors are increasingly allergic to startups that are too focused on building the tech without understanding the use case,” he said. Even worse than that, he added, is building something that sounds innovative but cannot justify its real-world cost structure.

The uncomfortable question, as he puts it, is, “are customers actually willing to pay for your GPU bill?”

The challenge lies in the behavioural side, not the technology. Solve for Indian users well enough, and you don’t just build a product, you build a durable business

– Arpit Mittal, SpeakX founder

When OpenAI, Azure, and other large language models form the base layer of most AI applications, models stop being the differentiator, argued SpeakX founder Arpit Mittal. The advantage lies in the use case — and Indian founders have a structural edge here. Indian customers demand extreme localisation and push products harder. Startups have no choice but to adapt to survive.

“The challenge lies in the behavioural side, not the technology,” said Mittal. “Solve for Indian users well enough, and you don’t just build a product, you build a durable business.”

With AI, Indian founders can build new consumer experiences and stress-test them on a massive market.

Rajan Anandan, too, pointed at India’s sheer scale as a forcing function. With over 900 million internet users, the country is emerging as a proving ground for AI-native consumer products. Four out of five consumer AI companies in Peak XV’s current Surge cohort are India-focused.

In this environment, the market is not a constraint, demonstrating value is.

Also Read: Let’s talk about red tape, cash flow, say Indian startup founders

What do AI startups really own?

Venture capital today is less interested in which model a startup uses and more concerned with what core asset it owns. If anyone can access the same LLMs and infrastructure, what prevents a fast follower from cloning the product?

“What will you own tomorrow that AI itself cannot take away?” asked Achintya Gupta of Reo.Dev, noting that email generation is already a commodity.

Capital, he argued, is no longer the toughest hurdle. What’s more difficult is building durable partnerships and embedding products deeply into customer workflows, in ways competitors cannot easily dislodge.

Karpe warned that many AI startups will fail for reasons that have little to do with model quality. Rising inference costs, weak pricing discipline, and churn can wipe out companies long before bad technology does. What will shock founders is not failure, but how quickly “promising traction” evaporates when unit economics collapse.

“In hindsight, the ecosystem will realise it overestimated technology and underestimated execution,” he said.

But there’s also a risk in how AI is being built in India. While the most investment is happening in the application layer, there is a pitfall to it. If a startup’s entire value is built on a global model it doesn’t control, it has no say over its own costs or its technological roadmap. It’s the difference between owning and renting. And as AI becomes embedded across critical sectors, the question of sovereign AI grows harder to ignore.

Anandan sees the solution in a middle ground. India may not need to build a trillion-parameter behemoth, a complex AI ‘brain’, to compete with the West, but it does need models that it owns.

“India will absolutely build and win at the model layer,” he said. “But these will be smaller—think about models that range from 3 billion to 100 billion parameters—focused on Indic languages and Indian use cases. We will see the first amazing Indian models at the India AI Impact Summit in a few weeks.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)