New Delhi: At 32, Sapna Thakur looks back at the girl she once was back home in Bihar. She lost her sight at nine, grew up thinking she was the only blind person in her state, and was told she would never amount to anything. Her mother had to fight off relatives who wanted her married off simply because she couldn’t see. What changed her life was discovering what she could do with her hands.

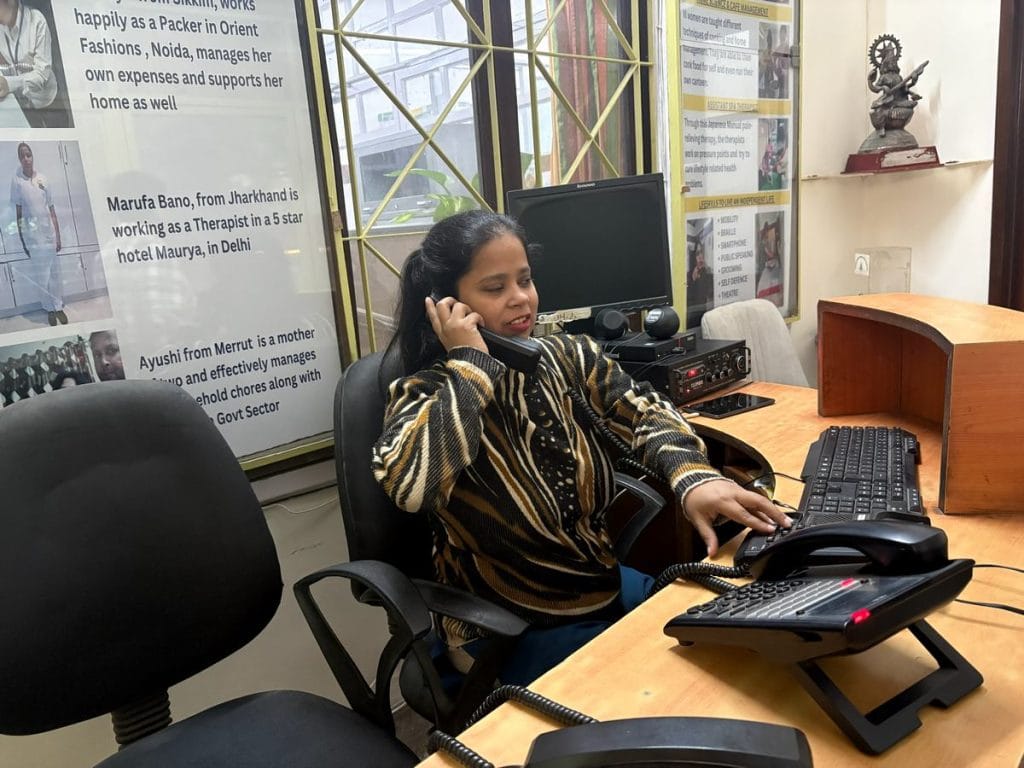

Today, she is a masseur, a new career frontier that has opened for blind people in the last five years in India. With a little bit of help from Japan. Four years at the NAB Centre for Blind Women in Delhi’s Hauz Khas gave her skills and confidence she didn’t know she could have. She now travels by metro alone, writes reports, and sends emails.

“I never knew I could become this version of myself,” said Thakur, who is employed as an assistant massage trainer at NAB. “Then one day I heard about NAB, came to Delhi with my husband and took massage training here. I’ve now been here for four years.”

Like her, hundreds of blind individuals have discovered that vision loss doesn’t mean loss of livelihood and selfhood.

In a country where blind people have long been confined to vocational activities such as making candles or handicrafts, massage training has opened up a new and more lucrative career path. In several Asian countries, including Japan, China, Sri Lanka and Malaysia, blind masseurs are preferred and respected for their tactile sensitivity. Their heightened sense of touch allows them to detect subtle muscle tension and knots with precision, often surpassing the abilities of sighted therapists.

I’ve always believed the problem isn’t disability — it’s discrimination. No one should hesitate to take services from people with disabilities. There is nothing to pity. Choosing their work isn’t charity, it’s giving someone dignity, agency, and the chance to build a life on their own terms

-Sanshe Bhatia, founder of The Maalish Co

India, too, is gradually recognising the dignity and independence that this work can offer. NGOs such as NAB and Blind Relief Association are among the first to tap into the potential of massage training.

“We need to study where persons with disabilities can excel, identify roles that align with their skills and focus, and design employment opportunities around their strengths,” said Nilika Mehrotra, Professor at the Centre for the Study of Social Systems at Jawaharlal Nehru University, known for her work on gender and disability. “Sometimes, because of their disability, individuals are even preferred.”

Nearly 5 million blind people and 70 million with visual impairments face unemployment. They are held back by stigma, limited education, and few chances to build meaningful skills. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act and schemes under the National Institute for Empowerment of Persons with Visual Disabilities (NIEPVD) promise employment support, but the gap continues to be substantial.

While blind people are already present across job sectors such as academics, banking, hospitality, and IT, there is growing attention on roles that draw directly on the sensory strengths they bring. With massage therapy, the first step is training and the next is employment. Businesses such as The Maalish Co are now actively hiring blind professionals and supporting a journey of ‘firsts’, each filled with growth and possibility — their first solo flight, first paycheque, first ride on the metro.

Also Read: Dementia wave is hitting Indian homes. Families are exhausted, healthcare unprepared

Daring to dream again

Sanjana, 20, had dreamed of becoming a doctor in her childhood. That dream came crashing down in 2017, when her vision began to deteriorate. The doctors told her there was nothing they could do. For days, she cried herself to sleep, unable to imagine a life without sight — not seeing her parents’ faces, the colours around her, the world she knew.

One day, she recalled, her mother sat down with her and said: “Sanjana, there are many people in the world who don’t have hands or legs, yet they live. They do things. They make a life for themselves.”

That’s exactly what Sanjana did.

She joined the massage therapy course offered by the Blind Relief Association (BRA) in Delhi, and once she completed it, The Maalish Co hired her. The job entails providing on-site massage services at different companies for a few days at a time.

I stopped dreaming the day my vision began to fade. But now, whatever I’m able to do, I feel proud. I decided I can’t just sit and wait. I want to do something with my life.

-Sanjana, masseur

Her first assignment took her to Pune, giving her the excitement of travelling alone by train and packing her own bag for the first time. Her parents were supportive but a little worried. Her next assignment was in Bengaluru, and this time she went on an airplane. There, she worked at two major companies, Myntra and EY. At Myntra, she gave 8-minute massages to 34 clients on the first day and 38 on the second.

When her work for the day was done, she wandered through malls. Everything seemed “too expensive,” but she still treated herself to a small perfume bottle with her own money. She grabbed a burger and a cold drink too, savouring each moment. It seemed like a dream.

Sanjana had always loved the idea of travelling, but when it actually happened, it felt almost impossible to absorb.

“I stopped dreaming the day my vision began to fade,” she said. “But now, whatever I’m able to do, I feel proud. I always had this passion to do something meaningful. I decided I can’t just sit and wait. I want to do something with my life. I want to live fully.”

Hands-on training

At BRA Delhi’s annual Diwali Bazaar, the crowd gathered eagerly, willing to pay Rs 200 for a 20-minute massage right in the middle of the market. The therapists, all visually impaired, worked tirelessly, pausing only briefly to eat or drink before returning to their chairs.

A man in his late sixties came in and booked two back-to-back appointments, paying Rs 400 for 40 minutes. While handing over the money, he said that he chose two sessions because “ye achha karte hain” (they do it well). Two women, who said it was their first visit, were already planning to return the next year.

Founded in 1944, BRA has for long provided vocational training for adults aged 18-35 in bookbinding, paper craft, chair caning, candle-making, and so on. But massage therapy has been one of its most impactful programmes ever since it was introduced in the early 2000s.

In a room with six massage beds at the BRA massage training room, about 12-14 young men worked in pairs, each focused on a friend, a classmate, or a walk-in client. They moved with a slow rhythm: first locating knots of tension, then pressing and loosening the muscles. The massage instructor, Shyam Kishore Prasad, circulated between the beds, adjusting a wrist here and correcting a thumb angle there. Anyone can book an appointment here, and a 90-minute session comes to roughly Rs 1,000.

Mobility is the main part. Once students learn to move independently, their confidence rises. We build that confidence by teaching them to travel on their own, use smartphones and computers, and take care of their grooming

-Shyam Kishore Prasad, massage trainer at the Blind Relief Association

One elderly man in his late seventies comes at least once a week. His doctor has advised regular massages; the pain in his back becomes unbearable if he skips a session.

The gaze, though, is still largely one of charity, not one of professional transactions.

“You’re helping them by giving them work, and at the same time, your own pain gets better—it really is the best of both worlds,” he said, smiling as he walked out of the room.

Prasad’s journey with BRA began in 2004 when he enrolled in the fourth batch of the massage training course. In 2010, BRA gave him a chance to teach. He trained four or five batches, but he had ambitions to do even more. While continuing to teach, he also completed a three-and-a-half-year naturopathy diploma at the Gandhi National Academy of Naturopathy in Rajghat.

For Prasad, training extends far beyond teaching massage techniques.

“Mobility is the main part. Once students learn to move independently, their confidence rises. We build that confidence by teaching them to travel on their own, use smartphones and computers, and take care of their grooming,” he said. Over the years, many of his students have gone on to secure government jobs, start independent practices, or become entrepreneurs.

Yet work remains fragile. Most opportunities are short-term or event-based — at embassies, hotels, corporate offices, Diwali bazaars, or pop-ups at places like Delhi Metro or Saket Mall.

“But this is enough for these young people,” said Prasad. “Some have come from Bihar, some from UP or MP. Some have come on their own, others were sent by their parents with hope for a better future. The only expectation is that they become capable and able to support themselves.”

A Japanese touch

At NAB’s open-air café, Blind Bake, trainees measure, pour, and stir with precision, letting their fingertips follow the curves of each measuring spoon to get the portions right. Walkers and runners stop by for coffee and pastries. In the adjoining training kitchen, hands chop, clean, and cook, with a trainer hovering over them.

Life moves slowly here, deliberate, a chain of hands guiding each other.

This is the world Shalini Khanna has spent more than two decades building. As director of the NAB India Centre for Blind Women and Disability Studies, she has run the country’s only residential centre exclusively for blind women since 2002.

Over the years, the centre has added several practical, skills-based programmes: Blind Bake, a café run entirely by visually impaired staff; Ujwala, which focuses on handicraft work; Discovering Hands for early breast cancer detection; and Talking Hands for massage therapy.

Blindness here is not viewed as a limitation but as an advantage in roles where precision, focus, and touch matter most.

“Sight can mislead you, but the hands don’t lie,” Khanna said.

A visit to Japan in 2013 crystallised this understanding. There, she realised that massage wasn’t viewed as a wellness extra but as a respected, science-based profession — one that recognised the considerable strengths of blind people.

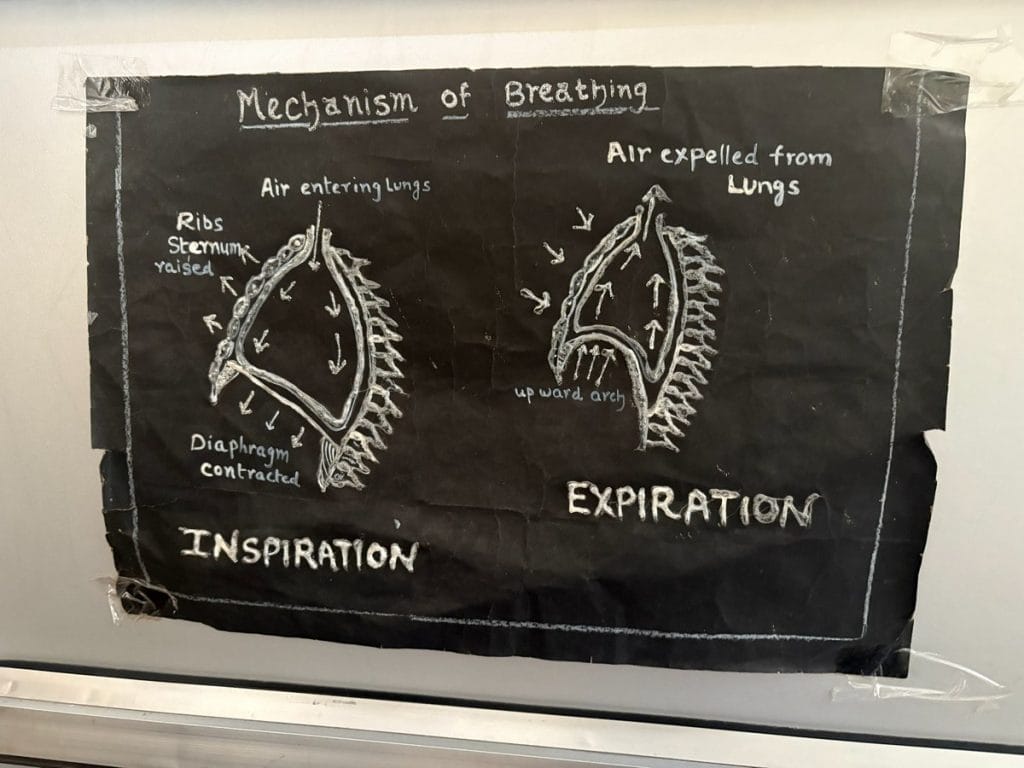

“I saw blind children studying anatomy and the nervous system, and how years of reading Braille had sharpened their fingers beyond anything sighted people typically develop. The therapists I met could locate nerve blockages and stress knots with striking accuracy,” she said.

In Japan, schools for the blind routinely teach shiatsu (or amma, a massage therapy focused on pressure points) alongside anatomy and physiology, preparing students to become certified therapists. China follows a similar path. Since 2016, blind masseurs there have been legally recognised under the Law on Traditional Chinese Medicine, allowing them to work in clinical settings and command better incomes.

Training without jobs is demotivating. A skill only becomes empowering when it leads to income. Southern states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu, with their strong wellness and Ayurveda industries, offer far more opportunities

-Shalini Khanna, director, NAB India Centre for Blind Women & Disability Studies

Driven by this insight, Shalini brought Japanese amma massage and pain-relief techniques to India — first to Dehradun’s NIEPVD, then to Delhi. She introduced structured training in relaxation, manual therapy, and foot reflexology, and also invited Japanese experts to refine the programme.

Still, in many parts of India — especially the North — massage work is undervalued, and safe, dignified employment for blind women is rare.

“Training without jobs is demotivating. A skill only becomes empowering when it leads to income. Southern states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu, with their strong wellness and Ayurveda industries, offer far more opportunities,” she said.

South India’s Ayurveda clinics and wellness centres have long raised demand for trained massage therapists, including opportunities for the visually impaired. Odisha’s NAB unit is also tapping into this expanding network of spa chains, wellness hubs, and medical tourism facilities. Many of their trainees now work in Chennai.

Business, not ‘charity’

Before starting The Maalish Co, Sanshe Bhatia had always gravitated toward social work but framing it as charity never sat well with her. It was during two intense years with Teach For India, working in under-resourced schools, that one girl with disabilities in her junior-wing class made her rethink what real “empowerment” looked like.

“I didn’t want to start an NGO. I wanted to play to their capability, not on the sympathy card,” Bhatia said.

Organisations such as NAB and BRA open doors for blind individuals to receive training, but Bhatia wanted to go a step further and hire visually and hearing-impaired therapists. First, though, she needed to find a market. During the long, introspective months of COVID, she began observing what ‘employee wellness’ looked like in corporate India and where massage therapy could fit in. In 2024, she finally launched The Maalish Co.

“Employee wellness here isn’t great,” she said. “It’s like, ‘feed me samosas on Friday’. That’s not wellness.”

Massages, she realised, were ideal for corporate wellness: simple, portable, low-resource, and genuinely relieving for fatigued desk-bound workers. And if skilled visually impaired and hearing-impaired therapists delivered those massages, the model could work without slipping into one-off CSR events.

Her first break came from a friend’s father who ran a small firm. Bhatia arrived with no uniforms, no specialised chairs, and just two trainees — both deaf girls she had trained in a spare room she had converted into a makeshift office. The employees loved the massages. A month later, on Women’s Day, another friend called: her boss wanted something special for the team. Bhatia rushed to print T-shirts, gathered her trainees, and headed over. They worked for six straight hours, offering crisp 15-20 minute massages rooted in Ayurvedic pressure-point relief—exactly what screen-slumped employees needed.

Everything we are able to do now is a dream. Others like us might not even imagine that it’s possible. They are trapped by society, by their families, even by themselves

Sapna Thakur, masseur

Maalish was working. She soon began partnering with blind schools, the Noida Deaf Society, NAB Delhi, BRA, and others to hire trained therapists. With onboard trainers, she refined their skills further. She sent teams in pairs to new cities, supported their mobility needs, and slowly built their confidence.

There were painful moments, too.

“Some people say, ‘Oh, they’re blind, they’re deaf, we don’t want work done from them.’ But if this doesn’t happen, the alternative is they beg. Or stay dependent,” Bhatia said.

Still, the work spoke for itself. The company has worked with Nvidia, Walmart, LinkedIn, Myntra, and several others. It now has 38 therapists working across Mumbai, Pune, Delhi, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Chandigarh.

And with that expansion, lives have shifted. Sardia, a therapist from Manipur, bought her mother her first smartphone; Sanjana took her first-ever flight; Ambika is helping his family build a home near Dehradun; and Deepak, who lost his eyesight overnight and later his wife to depression, is funding the education of his three young children alone.

“I’ve always believed the problem isn’t disability — it’s discrimination. No one should hesitate to take services from people with disabilities. There is nothing to pity. Choosing their work isn’t charity, it’s giving someone dignity, agency, and the chance to build a life on their own terms. That’s something to be proud of,” Bhatia said.

Also Read: Inside UP’s PM Shri testing ground: Labs, smart boards and a race to catch up

Fragile futures

Like Sanjana, many blind therapists dream of having meaningful work, but for some, the future is still uncertain.

One of them is Adya Sharma, who tells everyone she is 14, though her trainer at NAB, Reva Dharni, says she is closer to 20.

A year ago, Adya’s hands were stiff and awkward, making it difficult to apply the precise pressure required in massage therapy. With daily practice — pressing, stretching, and refining her thumb movements — her hands have improved, though not yet to the level required for professional work.

In the training room, 74-year-old Dharni stands beside her as Adya works on a friend, instructing her patiently: “Adya beta, how many times have I told you, go slowly, don’t rush.”

Adya is among the more vulnerable trainees in the class. She says her birth parents abandoned her on the road to die. At times, she expresses her frustration that other trainees are picking up massage skills faster than she is.

“Some of them struggle simply because of the way they were born. Practice improves them, yes—but sometimes, not enough to meet the standards. We worry, what will happen to them?” said Dharni.

Nearby, Pooja Kumari, 22, is already a trained therapist. She moves her thumbs and fingers with precision — pressing, kneading, and tracing circular motions calmly.

Kumari loves singing Lata Mangeshkar’s songs, and her friends say she’s genuinely talented. She says shyly that she dreams of becoming a singer one day, as if the thought itself feels too big to be real.

“I don’t know if dreams ever come true,” she added.

But Sapna Thakur says what they’ve already accomplished was once a dream — having a life of their own and living it on their own terms.

“Everything we are able to do now is a dream. Others like us might not even imagine that it’s possible. They are trapped by society, by their families, even by themselves.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)