Chennai/New Delhi: The closer one gets, the more the outer cordon asserts itself. Motion-detecting pan-tilt-zoom cameras peer at the Chennai pavement, flanked by walls so thick they’d stop a charging elephant.

This isn’t a military site or a glass-and-steel BPO campus. This is India’s brisk march into the brave new AI world. It’s where your data is parked.

India is in the thick of a data centre sowing season, with an early-mover edge for Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Visakhapatnam, and Pune.

“It’s a trickle right now. It’ll become a stream and a flood,” said Praveen Krishna, the environmental, social and governance head at Sify Technologies, which operates the heavily fortified 130+ MW hyperscale facility in the SIPCOT IT park in Tamil Nadu’s Siruseri. Across India, the Fortune 500 Indian IT giant runs 14 such facilities, including India’s first data centre, set up in Navi Mumbai in 2000.

As the SEZs of the AI age, these data centre clusters are positioning India as the second-largest market in the Asia-Pacific, valued at $9.79 billion today and projected to reach $21.03 billion by 2031. Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon and Meta have together pledged over $40 billion in the last six months to build or expand capacity here. For India’s IT sector, this is the next big leap—a chance to drive full throttle into the era of AI-ready data infrastructure.

“We invite the whole world’s data to reside in India,” PM Narendra Modi said last week, pitching the country as a global data hub ahead of the ongoing India AI Impact Summit 2026.

Not too long ago, Indian data lived on servers across the Bay of Bengal in Singapore. That is no longer the case. Net banking, cloud files, and streaming content are now stored in data centres on home soil. Union Minister for Electronics and IT Ashwini Vaishnaw noted in a post-Budget statement that nearly $70 billion in investment is already underway, with commitments of another $90 billion.

Tamil Nadu has consolidated its position as a leading data centre hub for India through policy coherence, infrastructure depth and most importantly capacity to enable execution of projects at record pace

-TRB Rajaa, Tamil Nadu Minister for Industries, Investment Promotion and Commerce

The leading US-based data company S&P Global estimates that over 95 per cent of India’s data centre capacity increase over the next five years will come from leased, retail, and wholesale facilities, with the remainder from “hyperscalers” building dedicated AI infrastructure.

Ambitions are already stretching even higher. By the end of 2026, Chennai-based AgniKul Cosmos and Bengaluru’s NeevCloud even plan to launch India’s first orbital AI data centre, joining an international space race along with players like Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

Yet on the ground, this is still the first 40 metres of a sprint for India. While the country is said to account for 20 per cent of global data generation, it has only 3 per cent of global capacity. By comparison, the US has upwards of 4,000 data centres, and the UK, a distant second, nearly 500.

“At current standing, India’s installed data centre capacity is roughly 1.5 GW. Europe’s is about 10-12 GW across major markets. So, to a certain degree, India’s behind where it should be in terms of data centre capacity,” said Jonas Topp-Mugglestone, a London-based researcher with telecoms consultancy STL Partners, who specialises in data centres.

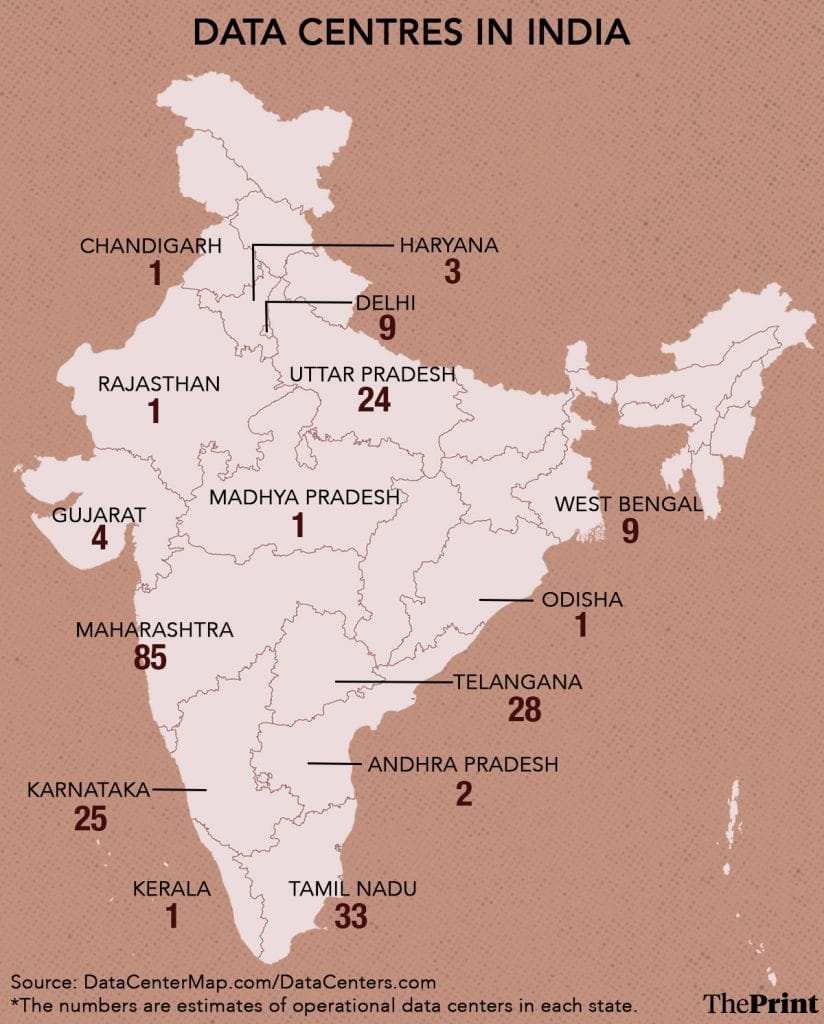

Latest industry estimates put the number of data centers in India at over 270, up from around 138 in 2022. While Topp-Mugglestone argued that India isn’t setting up data centres fast enough, he conceded that things are changing, “which is a good thing for India”.

“India, to a degree relative to its economic and population size, is kind of playing catch-up in a certain sense,” he added.

It is, after all, the world’s largest consumer of data. From just 1.24 GB in 2018, the average Indian now burns through 25 GB of data each month. The global average is 21.6 GB.

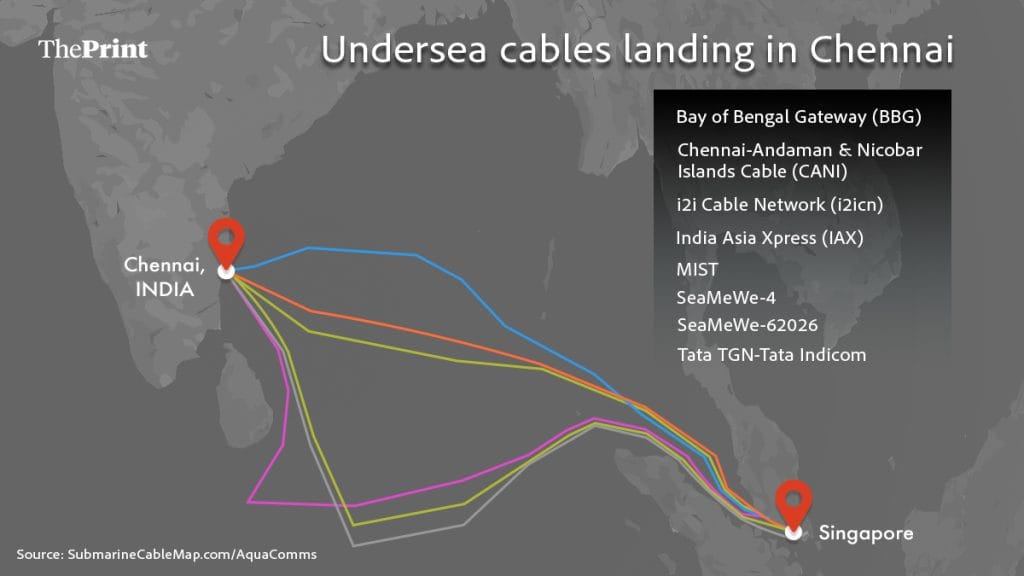

With 101.8 crore active users and counting, demand in India will only go up. And because data lags the farther it travels, the need for centres closer to the end-user is becoming more urgent. About 99 per cent of the world’s data flows through submarine cables.

Also Read: Inside India’s only dark factory in Tamil Nadu. Robots work all night, engineers stay out

Data comes in waves

Along the Buckingham Canal in Siruseri, Sify operates a cable landing station where undersea fibre optic cables come ashore after travelling thousands of kilometres across the ocean floor.

From the landing station, the cables run underground into the Meet-Me-Room (MMR) at Sify’s Rated 4 hyperscale facility, Chennai 02. Inaugurated by Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin last April, the campus comprises three towers, expandable both vertically and horizontally.

“It’s a pay-as-you-go service,” said a Sify representative, pointing out that it is the first such facility that allows transitioning hyperscalers who do not want to invest upfront.

From a conference room on the 11th floor of the middle tower, the representative presses a button. The blinds behind him part and, through a glass panel, a room straight out of a James Bond movie reveals itself.

It features 32 screens monitoring every inch of the floor layout and external perimeter. Motion-detecting cameras relay live visuals from 16 angles per screen. The feed is closely observed around the clock by six to eight site engineers working in shifts. Other screens in the command and control centre show an overview of the floor layout, local and international news, and real-time environmental data including wind speed, temperature, and humidity.

Where data lives

Data centres are built like fortresses, with vault-like layers of security.

Sify’s Chennai 02 facility is heavily guarded. Entry is strictly by employment or invitation. Inside, access cards and facial recognition sensors restrict elevator use and movement. An alarm goes off each time a door is open for more than 30 seconds.

Like veins in a body, cables run throughout the data centre on a system of parallel tray paths. These cables transmit data to and from thousands of servers hosted in data halls.

Entrance to each data hall requires another round of frisking, a biometric acceptance and finally, stepping on a blue-coloured sticky mat to strip dust particles from shoes.

Inside the halls are black cabinets of cold-rolled steel, where servers are piled on top of each other in rows. These racks are the primary units for data access and transmission. Customers can lease anything from half-a-rack to five hundred.

The racks are arranged in a tightly controlled environment, with ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ aisles. Hot aisles suck up the heat generated by the hardware on the racks, while cold aisles blast chilled air to maintain optimum temperature.

Each corner is fitted with temperature and humidity sensors that feed into the closed-loop cooling system.

The heart of this advanced system is located on the top level of the building, linked through a network of pipes. It also has a dozen rocket-shaped thermal tanks that can store up to 16,000 kilolitres of water.

This industrial terrace is the signature look of data centre clusters. In Siruseri alone, the SIPCOT IT park houses about 30 such facilities tucked between corporate offices. Major operators include Sify, Adani, Microsoft, IBM, NTT, Airtel, Reliance, Yotta, and Equinix.

‘No downtime in 12 years’

Barely 10 minutes from the Sify facility in Siruseri is CN1, a 30 MW+ colocation data centre operated by the US-headquartered Equinix. Inaugurated by Stalin last September, this AI-ready facility features an intruder detection system comprising hundreds of cameras and radar detection.

Besides racks on demand — including secured caged sections inside data halls— Equinix offers clients access to a software-defined backhaul linking the over 275 data centres it operates in 36 countries across six continents.

“There’s been no downtime in the last 12 years, not even one minute,” said an Equinix representative, referring to the company’s data centres in India.

Along the route to the data halls, he pointed to the network of communication cables overhead. Power and mist pipes run below each pathway. Inside the data hall, Equinix employs a patented cool array technology. Hot air exiting the back of the racks is sucked and pushed into a ‘cool spine’. Once the air is cooled, it is recirculated.

Customers here range from internet and cloud service providers to banks and large-scale enterprise firms employing upwards of 1,000 people.

However, even as the data centre industry grows at an exponential rate, it has found a formidable foe in the climate lobby.

A song of ice and fire

Data centres consume massive amounts of power and water. A single ChatGPT query, for instance, uses nearly 10 times as much electricity as a Google search. Depending on local conditions, an AI chatbot needs between half and three bottles of water to draft a 100-word email, according to a University of California study.

In industry parlance, the terms used to measure efficient usage are PUE and WUE—power and water usage effectiveness, respectively.

The scale of electricity required is enormous. India’s IT load capacity totalled 1.4 GW in Q2 of 2025, nearly triple of what it was in 2019, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. The Japanese financial services firm Nomura predicts this will go up to 9 GW by 2030. If this is accurate, data centres will account for 3 per cent of all power generated in India within four years, as opposed to less than 1 per cent now.

At the Sify facility, the total proposed capacity is 130 MW drawn from the national grid. To manage contingencies, the facility maintains eight diesel generator sets that can guzzle 600 litres of fuel per hour. At Equinix’s CN1, each data hall has an independent DG set, transformer, UPS, batteries, and panels to ensure an uninterrupted power supply, with up to 50 hours of diesel backup available at full load, if the grid fails.

One way that data centre operators offset fossil fuel usage is through clauses in power purchase agreements with the government. Under these arrangements, they buy renewable energy across multiple projects to meet carbon commitments.

Water-cooled data centres aren’t necessarily evil but in the wrong locations and using designs that aren’t really best suited to the environment they are effectively converting local freshwater into heat exports at the worst possible times

-Jonas Topp-Mugglestone, data centre researcher

SIPCOT managing director Dr K Senthil Raj told ThePrint that besides leasing land, the organisation earmarks parcels for the Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation to set up sub-stations dedicated to data centre clusters.

Topp-Mugglestone pointed out that one of the main problems India will face in expanding data centre capacity is power availability.

“People underestimate it but it’s the main constraint of data centre growth,” he said. “Historically, whoever has been responsible for the local power grid has overlooked it for the last 30 years. In America, for instance, the grid infrastructure is quite outdated,” he added.

The other big challenge is water.

A medium-sized data centre (1-5 MW) can consume up to roughly 110 million gallons of water per year for cooling purposes, according to Washington-based non-profit Environmental and Energy Study Institute (EESI). For larger facilities (100 MW+), this volume can go up to 1.8 billion gallons.

The Economic Survey 2025-26 pointed out that AI-ready data centres can consume up to 20 lakh litres of water daily, and that globally, they already use 56,000 crore litres each year.

Over the next four years, India’s annual data centre water usage is expected to more than double from 150 billion litres to 358 billion litres, according to the World Bank.

This, warned the Economic Survey, “has the potential to add an extraordinary amount of stress on our already strained groundwater and freshwater reserves”.

“Water-cooled data centres aren’t necessarily evil but in the wrong locations and using designs that aren’t really best suited to the environment they are effectively converting local freshwater into heat exports at the worst possible times,” said Topp-Mugglestone.

Mechanisms do exist to mitigate this strain. Raj said that SIPCOT does not tap into groundwater for Chennai’s industries. Instead, the city’s sewage water is treated and supplied to the clusters.

“A million litres is generated per day and sent to all industries in and around the Chennai region,” he said. “This is potable quality water.”

The question of sustainable growth apart, India’s data centre boom isn’t slowing anytime soon. It is, after all, the harvest of a growing season that began about a decade ago.

Also Read: Meet the VCs powering India’s AI boom. Old rules aren’t working anymore

Ambattur rising

The first spark for India’s data centre boom was lit in 2018, when the RBI mandated that financial data be stored within the country. Two years later, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology released a draft data centre policy proposing incentives, dedicated economic zones, and recognition of data centres as key infrastructure.

In 2024, the Centre launched the IndiaAI Mission with an outlay of Rs 10,370 crore to procure graphics processing units (GPUs). In her Budget speech last month, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a tax holiday until 2047 for foreign companies providing cloud services to customers through data centres located in India. She also proposed a 15 per cent safe harbour on costs for Indian companies providing these services, with a threshold of Rs 2,000 crore.

Some states jumped on the bandwagon before others. Telangana, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka were among the first to release dedicated data centre policies, some as early as 2016.

Tamil Nadu’s policy proposed single-window clearances, waivers of up to 45-50 per cent on cross-subsidy surcharges, and full exemptions on additional surcharges for renewable energy procurement.

“Tamil Nadu has consolidated its position as a leading data centre hub for India through policy coherence, infrastructure depth and most importantly capacity to enable execution of projects at record pace,” Tamil Nadu Minister for Industries, Investment Promotion and Commerce Dr TRB Rajaa told ThePrint.

The state government, he added, is now encouraging operators to go beyond established clusters such as Ambattur and Siruseri.

“Investor confidence is evident in projects such as Blackstone’s recent Rs 10,000 crore hyperscale campus in Ambattur, representing long-horizon capital commitment to Tamil Nadu’s digital infrastructure ecosystem. Power reliability underpins this expansion through dual grid access and dedicated feeders for high-capacity data centres,” the minister said.

Tamil Nadu has more than 30 operational data centres and West Bengal has 10. Maharashtra has around 85, the highest concentration in the country; the state, which released its IT and IT-enabled services policy in 2023, cut power tariffs for data centre operators by nearly 40 per cent.

Today, Chennai and Mumbai together account for roughly 70 per cent of India’s total data centre capacity.

Back in Chennai, there are two data centre frontiers. While the Siruseri cluster anchors the southern edge, Ambattur is rising as its counterpart in the north.

This 1,300-acre estate, established by TANSIDCO in 1964, is still home to more than 1,500 MSMEs, but its skyline is now being colonised by data centres.

The intricate facade of NTT’s twin-tower hyperscale facility is a landmark visible from a mile away, boasting a 34.8 MW capacity. To its left is the 100 MW Digital Connexion facility, a joint venture between Reliance Industries Ltd, Brookfield, and Digital Realty.

Across the street, there’s a giant naked steel structure taking form, cranes circling overhead. This one’s Iron Mountain. A board out front sums up the new era of India’s IT boom: “Construction of data centre.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)