Kancheepuram: It’s half past midnight in Kancheepuram’s SEZ. The UV lights are on in what looks like an almost emptied-out factory floor. Its eerie silence is broken by a quiet melodic beep, like an ICU’s heart-rate monitor, and the swish of a robotic arm slicing through air. It’s a new kind of factory soundscape. There are no human beings.

Welcome to India’s only dark factory.

Here lies the sanctum sanctorum of the country’s industrial future—robots assembling semiconductor chips without any human supervision. In what is called a cleanroom, there’s a silent rhythm of titanium hands performing an intricate, choreographed dance, set against the hypnotic loop of a Ganesha prayer.

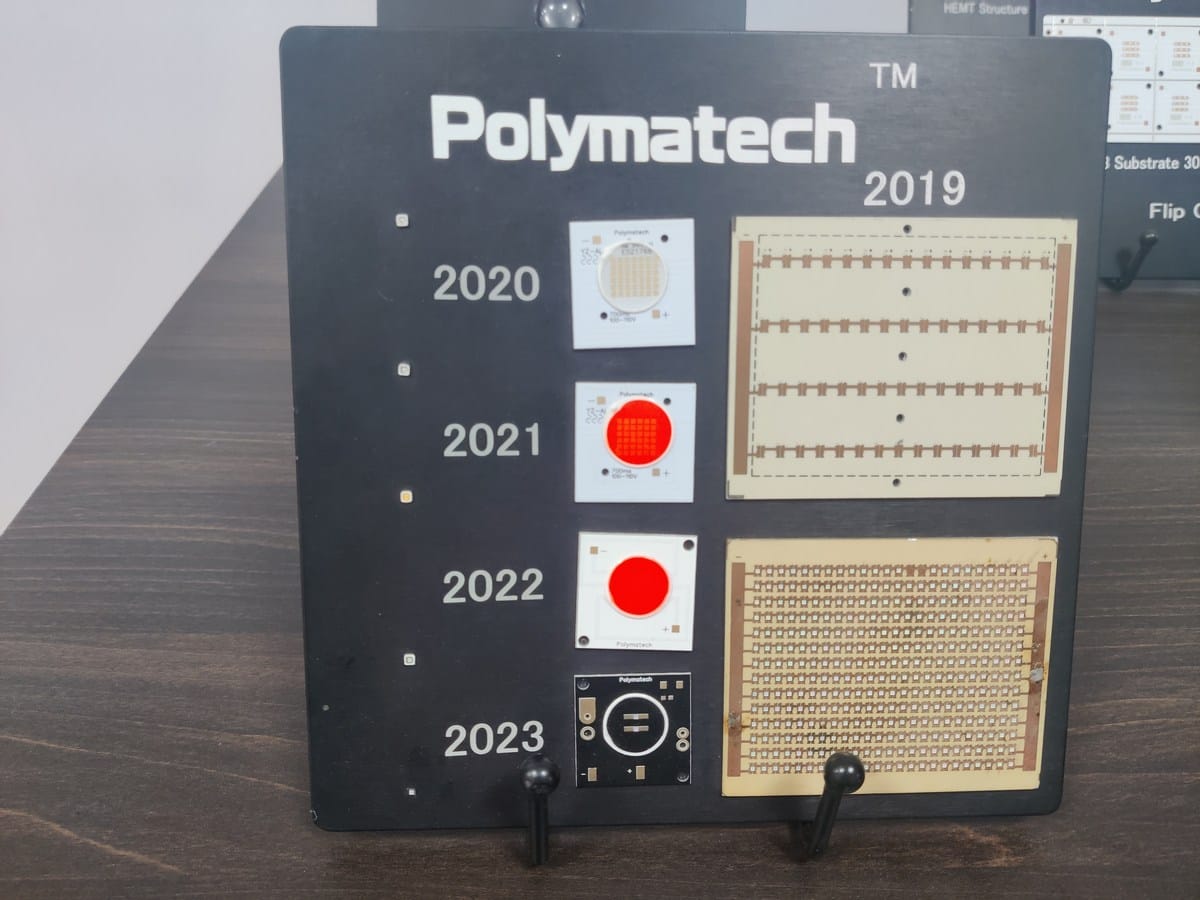

The semiconductor manufacturing unit, Polymatech, set up in 2018 in Kancheepuram’s Oragadam, stands at the cusp of the next industrial revolution. It’s a hyper-automation setup, turned ‘upside down’, where a handful of people and an army of machines produce goods faster, at a fraction of the cost, without compromising on quality.

“I want the engineers to sit outside the shop floor. I don’t want them to work; it’s only the machines that have to work,” said Vishaal Nandam, director at Polymatech. The robots here work 24×7, with a 30-minute break once a year. The engineers, by comparison, have no fixed shifts.

With the vigour of a well-drilled battalion, robots here assemble the semiconductor chips and printed circuit boards (PCB) that breathe light into mobile phones, laptops, and TV backlights. Precision down to the last nanometre is a non-negotiable key result area (KRA). The robots have their own call signs held up through stack lights affixed to the side of each machine. Red is a hiccup, yellow is ready-to-roar, green is clear sailing.

Having missed the China-style job-generating manufacturing boom, India is also a slow mover on roboticised, largely unattended manufacturing processes. Facilities like the one in Kancheepuram are rare. India is sixth in annual installations, with a manufacturing robot density of 9 robots per 10,000 employees. Asia’s is 204, and the global average is 177. At the top of the leaderboard are South Korea (1,102), Singapore (770), China (470), Germany (429), and Japan (419).

But when it comes to dark factories, the race has only just started.

Also Read: Meet the VCs powering India’s AI boom. Old rules aren’t working anymore

Working with robot ‘colleagues’

At the dark factory in Kancheepuram, the cleanroom corridors are sanitised at daybreak by workers under UV lights, while the main factory floor outside buzzes with engineers taking notes on maintenance, stocktaking, and orders.

“It is my first experience working with these robots. It is very unique and different to see,” said Dinesh S, 25, an engineer seated at a conference room-sized table adjacent to the managing director’s glass-walled office. A mechanical engineer from CCMR Polytechnic College in Thanjavur, Dinesh has been with Polymatech since 2022.

The engineers at the unit don’t work all day or clock in at 8 am to a factory siren. They come in for a few hours, keep an eye out for glitches, but mostly leave the robots alone.

Dinesh said he sees these robots as “colleagues” even if they don’t share a meal in the break room or swap jokes by the water cooler. Between them, each flicker is a signal, each beep an office memo.

Fellow engineer KV Mani Gopal, 25, differs.

“The robots can’t share feelings with us, so I can’t see them as colleagues,” said the electrical engineer from Andhra Pradesh’s GMR Institute of Technology. Dressed in a Polymatech t-shirt like the other engineers, he flinched slightly at the idea.

Dinesh and Mani are among the few who get to step inside the cleanrooms to replenish raw material magazines once every 18 hours. They wear PPE kits and endure an air shower before entering to keep out dust particles or pathogens.

If there is any power outage or fluctuation, all these machines that are running—I think about $1 million will be lost in one fluctuation

Vishaal Nandam, director at Polymatech

For both young engineers, this was their first job right out of college. It was unlike any their batchmates bagged—site engineer overseeing sheet metal processes, or quality engineer with an automobile giant.

“In each job, there’s a way of doing things. I don’t compare. My work is creative and I enjoy doing it,” said Dinesh, referring to the time he now spends in Polymatech’s R&D lab as the robots need little supervision. Just recently, the R&D team developed a vein-finder that can track veins and project them on the skin. Apart from having more time to spare for research, work-life balance is easy to pull off as well.

The ratio at this facility is roughly 25 robots for every 100 employees. Profiles include engineers who supervise manufacturing and engage in R&D, as well as account managers and sales and marketing staff. There’s also a smattering of support staff for security, housekeeping, and administration.

“Everyone here has a Vitamin D deficiency. It’s a dark factory after all,” joked Vishaal Nandam.

The first movers

In Kancheepuram’s Oragadam, this brush with hyper-automation began nearly a decade ago. Not far from Polymatech’s 150,000-square-foot facility, robots took over the paint line at Royal Enfield’s plant in 2015. This was a “lights-sparse” setup, with the dark factory model limited to parts of the shop floor.

It was a small first step into a world pioneered by Japanese robotics giant FANUC, which set up the world’s first dark factory near Mount Fuji in 2001. Unlike their ancestors, which might accidentally paint themselves instead of the chassis, these robots embodied ruthless efficiency. In a sense, they were ‘procreating’ — manufacturing more robots with no human supervision for weeks on end.

India continues to grow with a record of over 9,100 units installed in 2024—up 7 percent year-on-year

– Carsten Heer, International Federation of Robotics

Because automotive assembly lines demand precision, repetition, and scale, the sector became an early adopter of dark factories. Of the 9,123 industrial robots installed in India in 2024, nearly half were added by this sector alone.

“Robotisation and automation across the globe have been confined to two sectors. One is automobiles and the other is chip manufacturing. Beyond that, nowhere in the world has it gone any further,” said Santosh Mehrotra, visiting professor at the Centre for Development, University of Bath, UK.

Others are catching up. For instance, Bharat Forge, the Rs 66,000-crore conglomerate, entered into a collaboration with Germany’s Agile Robots SE in January 2026 to “develop and deploy state-of-the-art vision and AI based robotic solutions…to enable a fully autonomous (‘dark’) factory”.

Data maintained by the International Federation of Robotics reflects this momentum.

“India continues to grow with a record of over 9,100 units installed in 2024—up 7 percent year-on-year,” said federation press officer Carsten Heer. He added that India currently ranks 10th in operational stock, ahead of Spain and after Mexico. Between 2019 and 2024, the number of industrial robots installed annually in India rose by 112 per cent.

Players such as Polymatech are betting big on the dark factory model, with a new facility coming up in Chhattisgarh. A ‘zero manpower’ facility in Singapore is also in the works, said MD Eswara Rao Nandam, seated before a large photograph showing him presenting his company’s vision to PM Narendra Modi at SEMICON India 2025.

A dark factory in a garage

Around 500 kilometres from Kancheepuram, on the other side of Tamil Nadu, a group of engineers in their early 20s has taken it upon themselves to sow the seeds of a dark factory revolution in India, one robot at a time.

They are the evangelisers of dark factories, and they have a prototype in Coimbatore. CEO Dhanush Baktha envisions a metal fabrication market where manufacturers no longer buy machines or set up their own units; instead, they place orders with dark factories operated by his firm, xLogic Labs.

On an August night last year, Dhanush and his team clattered about, building their first robot. Around 3 am, there was a knock on the shutter. It was the police.

“They came in and asked, ‘What are you doing?’ After that, they were curious about what we do. They just came and saw it for two minutes and then just left,” he recalled.

The real obstacle is scaling up. While the Tamil Nadu government has multiple schemes and is proactive about automation, when it comes to startups the needle can take a long time to move.

“It takes too long for government incentives to materialise, which is why we’ve had to rely on grants and funding from the US to expand. An investor from the US literally gave me some Rs 1 crore within two minutes of me pitching the idea,” said Dhanush.

Staying true to the Silicon Valley rite of passage, xLogic Labs currently operates from a garage in Coimbatore. Tucked away in the heart of a residential neighbourhood, this is their ‘prototype factory’. A robotic arm juts out from each corner. Electrical wires are strewn around and machines occupy nearly every inch of space. Racks filled with electronic equipment double up as room partitions. A massive tricolour stands in the middle, keeping company with a makeshift crane.

Anyone looking to set up a dark factory will have to spend at least four to five times more than we are spending because they will have to import machines, and we’re building them on our own

-Dhanush Baktha, founder of xLogic Labs

Over the last five months, the five-member team has built three robots, including one they call ‘the magician’. It can perform functions that would otherwise require 10 separate machines.

“We can of course buy Chinese or German machines, start offering services and make money. But we don’t want to do that. We want to use our own machines from day one because here you’re forced to innovate, and forced to innovate sooner,” said Dhanush.

The dream is to build robots that can switch between multiple tasks otherwise performed by semi-skilled workers such as machine operators or assemblers.

While the xLogic Labs team is small, it packs a punch. One member was part of the team that represented India at WorldSkills 2024, also known as the ‘Skills Olympics’. Another worked with a company making rockets in Germany. Of the five, two are from Tamil Nadu and one each from Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Punjab.

The haphazard appearance of the garage ‘prototype factory’ belies a sophisticated method that’s already won them a handful of clients. Their immediate focus is on fulfilling pending orders.

“Anyone looking to set up a dark factory will have to spend at least four to five times more than we are spending because they will have to import machines, and we’re building them on our own,” Dhanush said. “Also, building our own machines means we have access to manufacturing processes no one can offer and have a cornered technical resource, which is our ultimate alpha.”

He added that despite Coimbatore being an industrial hub, there’s a shortage of labour in the metal fabrications industry. The balance of power between labour and capital is tilting, and the market is feeling it.

‘This business is on its last legs’

The owner of a metal fabrication firm in Coimbatore said he switched to robots for cutting and bending a few years ago due to the labour shortage. But full automation is not within reach.

“Setting up a dark factory where robots do all the work will take a lot of money. Not everyone can do it.”

The walls of his shop floor are covered in soot and welding sparks fly in chaotic arcs. The labourers’ hands are visibly hardened by years of beating metal. It is a world where production still relies on sweat and muscle, even as the machines begin to edge closer.

In the Ambattur industrial area of Chennai, another metal fabrication facility was an almost exact replica of its Coimbatore counterpart—a dilapidated building with high ceilings, black-blotted exterior walls, and a few weary labourers. There too, a supervisor described an industry in the throes of a forced evolution.

“There is a shortage of skilled labour. To add to that, all processes—metal shearing, folding, and cutting—have shifted to laser,” he said.

The unit has machines that even metal fabrication firms averse to automation can’t do without: a welding machine, cutting and shearing machines, plate rolling machines, press brakes. Yet it isn’t enough to keep up with the automation juggernaut.

“Our owner wants to set up a new business, this one is on its last legs,” said the supervisor.

Two sides of the hyper-automation coin

In the Indian context, dark factories are frightening as well as exhilarating. This phenomenon has come against the backdrop of chronic unemployment and under-employment. Manufacturing has been stuck at 16 to 17 per cent of India’s GDP since the 1990s. Even the Make in India initiative has not moved it up. Agriculture contributes about 18 per cent of the GDP, but employs nearly half of the workforce.

The other problem is the shortage of a skilled, certified workforce.

Data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2023-24) paints a bleak picture of this gap: 22.15 per cent of Indian workers were classified as low-skilled (under Level 1) and 66.89 per cent as semi-skilled (under Level 2). Only 2.37 per cent fell under Level 3 and 8.59 per cent under Level 4.

We in India began to get serious about vocational skills only in 2010; that was 60 years too late

-Santosh Mehrotra, former chair of the Centre for Labour at JNU

“There is no question there is a skills crisis,” said Mehrotra. “This problem is solvable but not in the way it is being dealt with right now. Bureaucrats cannot solve it, they have no clue.”

Mehrotra argued that employers must be made a part of the skilling process, which hasn’t happened yet. “We in India began to get serious about vocational skills only in 2010; that was 60 years too late.”

But he is optimistic. “We can always catch the manufacturing bus at the next step.”

While Mehrotra does not see the shift to dark factories picking up pace just yet in India, there are signs that machines are slowly filling the skill vacuum.

Rockwell Automation’s State of Smart Manufacturing Report 2025 said over 90 per cent of the 78 respondents from India reported that obstacles they face—both within their organisation and externally—are accelerating digital transformation. Of the 1,560 respondents from 17 manufacturing countries, 41 per cent said they were introducing AI/Machine Learning and ramping up automation to fill skills gaps and address labour shortages.

For India, the implication is that low-skilled and semi-skilled workers who form the backbone of the current labour force are the most vulnerable to being replaced by robots and dark factories powered by AI and Internet of Things (IoT) systems.

These are the two sides of the hyper-automation coin: the hope of global competitiveness versus the fear of mass job displacement.

In its 2025 report on India’s services sector, NITI Aayog called for accelerated reskilling and upskilling, especially for mid-career professionals at risk of automation.

“The impact of automation on workers being complex and uncertain, the direction of technological change remains susceptible to forces of political economy,” it said.

Bracing for the ‘inevitable’

Institutions offering skill-based training in technical trades are bracing for the future. At the state-run Industrial Training Institute (ITI) in Chennai’s Ambattur, the strategy is one of pragmatic preparation.

“This automation is inevitable,” said its director Prabhakaran BE, pointing to the way robotics and AI are transforming everything from quality assurance to medical diagnostics.

The ITI he heads in Ambattur offers skills-based training in 28 technical trades to as many as a thousand students at any given time. Among these are industrial robotics and digital manufacturing, manufacturing process control and automation, and basic designer and virtual verifier (mechanical).

To keep pace with automation, the ITI also runs programmes in PLC (Programmable Logic Controllers), HMI (Human-Machine Interface), and SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) programming.

These are the holy trinity of the tech-forward factory floor. PLC is used to automate factory machines and processes; HMI is the interface operators use to interact with automation systems; and SCADA involves configuring software to monitor and control industrial processes through real-time data from sensors.

Inside one classroom, students as young as 16 sit in rows of four in front of computer screens. The teacher guides them through writing lines of code and sequences, building programmes, and defining when each will start, pause, or stop.

The students follow instructions closely as they learn to programme robotic arms and ATM machines. For these young people, born into the internet age, automation is not a frightening spectre but a reality they can be a part of. And there’s still some time before robots take over factory floors.

Two factors slowing this transition, at least for now, are what Dhanush calls the “robot deployment gap” and the “data scaling problem”.

Also Read: Gurugram startup grew a snakeskin shoe in a lab. It wants to make India a bioscience power

One fluctuation = $1 million loss

Despite giant robot manufacturers such as FANUC, ABB, and KUKA, mass deployment is yet to be seen in factories.

“If you see robot adoption globally also, it’s very low,” said Dhanush.

One country that took this challenge head on was China. When it launched its industrial transformation roadmap in 2015, its robot density was a mere 49 per 10,000 workers. Less than a decade later, it stood at 470.

With ‘data-scaling’, there is a chicken-and-egg problem. Dhanush said “hundreds of robots” must be deployed to generate training data. But large volumes of training data are required before robots can be deployed reliably.

“It means you have to spend a lot of capex just collecting data, generating no revenue for the next two years. Only then can you generate a million hours of training data, train your robots on those models, and deploy them in factories,” he added.

On top of this, even the most basic components needed to build a robot are not made in India.

“We have to start by indigenising every component that goes into our robots and that is what we’re trying to do,” Dhanush said.

Interruptions in power supply can also create very expensive problems for dark factories.

“If there is any power outage or fluctuation, all these machines that are running—I think about $1 million will be lost in one fluctuation,” said Polymatech’s Vishaal Nandam.

NITI Aayog’s roadmap addresses this issue. It suggests setting up 20 “Plug & Play Frontier Technology-enabled Industrial Parks” across the country, identifying aerospace and defence, semiconductors, electronics, automotive, and pharmaceuticals as the five most impactful sectors.

If India fails to adopt frontier technologies in these sectors, the report said, the country “will not only risk a historic window of opportunity… but also encounter a potential loss in additional manufacturing GDP to an extent of US $270 billion by 2035 and US $1 trillion by 2047.”

Despite these hurdles, there is little doubt that hyper-automation is already knocking on India’s doors. Back at the dark factory in Kancheepuram, the daytime shift is gone, but the robots continue their work in silence. On a monitor, a magnified view of the process shows a needle-like arm assembling a semiconductor chip before moving on to the next.

There are eight months to go before the next stretch break.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

This company has NCLT litigation from its creditors. Please don’t Promote companies with governance issues.