Dhar: Hundreds of Muslim men and children march to the beat of drums as a Muharram procession snakes through the narrow lanes around the Bhojshala-Kamal Maula Mosque complex in Madhya Pradesh’s Dhar district. A few hundred metres away, Ashish Goyal of the Hindu Front for Justice is preparing for the next high court hearing, determined to ensure the Bhojshala is ‘returned’ to the Hindus.

Goyal is buoyed by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)’s 15 July report, which states that the ‘existing structure’ was built using parts of an older temple dating back to the Paramara period between the 10th and 11th centuries.

“It was a gurukul for promoting Hindu culture,” says Goyal, who filed a petition in the Madhya Pradesh High Court against allowing namaz at the site.

The court-ordered ASI survey has reignited the age-old controversy over whose place of worship it is. Hindus call it Bhojshala, considering it a temple dedicated to the goddess Vagdevi (Saraswati); for Muslims, it is a mosque commemorating Kamaluddin Chishti. The central ‘battle’ in Dhar is now who gets to pray at the complex.

The dispute is threatening the tenuous ‘peace’ arrangement in place since 2003, when the ASI came up with a plan: Hindus will perform puja on Tuesdays and Muslims will offer namaz on Fridays. Local Hindutva groups, the RSS, and the BJP are rallying followers on WhatsApp to come and pray in large numbers this Tuesday. The Madhya Pradesh High Court will next hear the matter on Monday.

“Where in the world have you seen a mandir where people are allowed to offer namaz or a mosque where Hindus are allowed to do puja?” asks Goyal at his Gurukrupa showroom of furniture and electronic goods on the Dhar-Indore road.

Goyal seems to be taking a leaf out of the BJP’s playbook from disputes like the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya and Gyanvapi Masjid in Varanasi, even though recent election results have called into question the BJP’s temple politics. While the Bhojshala-Kamal Maula dispute did not gain much traction in the 2003 Madhya Pradesh assembly election, which ended the Congress’s decade-long rule under Digvijaya Singh, it has resurfaced multiple times since.

In 2022, the Shivraj Singh Chouhan-led government promised to “bring back” the Saraswati idol allegedly taken from the complex by the British in 1857. The issue was also key in Dhar district during the recent Lok Sabha election.

The ASI team reportedly found images of Hindu gods, including Ganesh and Brahma, as well as 94 sculptures and sculptural fragments during their three-month survey beginning 22 March. Abdul Samad, president of the Kamal Maula Welfare Society and the Muslim petitioner, has alleged violations by the ASI team.

“The point remains that it is an important tool in furthering the narrative of ‘freeing a religious place after they were snatched away by invaders’. In this context, Bhojshala holds significance in this politics of symbolism and can give dividends to the ruling dispensation in the days to come,” said Yatindra Sisodia, professor and director at the Madhya Pradesh Institute of Social Science Research in Ujjain.

Rallying Hindus, carrying on a legacy

At the ‘Maa Saraswati Akhand Sankalp Jyoti Mandir’ across from the Bhojshala-Kamal Maula complex, Sumit Choudhary, 32, flips through a booklet that “chronicles the four decades of struggles” by Hindus to ‘reclaim the temple’.

“I refer to this booklet to ensure my facts don’t go wrong,” says Choudhary, a second-generation RSS worker who now leads the Bhoj Utsav Samiti.

Choudhary coordinates a network of nearly 200 workers who spread the ideology of Raja Bhoj—the scholar-king of Malwa (modern-day Dhar) who ruled in the 11th century—and the history of the Bhojshala complex.

“Our workers—men and women—have been rallying Hindus in Dhar,” Choudhary says. “We are preparing for the upcoming Tuesday, circulating messages and letters across Whats app groups urging Hindus to join the puja in large numbers.”

One WhatsApp message appeals to Hindu pride and Dhar’s heritage: “Today, Dhar is no longer just a land issue but a question of pride and self-respect. The entire country is looking forward to the cooperation of Dhar’s Hindu community. Why should we not participate in greater numbers in this Satyagraha?”

Choudhary is carrying on his father Radhesham’s legacy. The elder Choudhary was among the sevaks who embarked on a rath from Dhar to the Trikut mountain in Maihar, Satna district. He returned with a lit torch, vowing to place it before the statue of Vangdevi when it is returned from London to the complex. The torch now holds a place of honour in the Jyoti Sankalp Mandir.

At the mandir, workers gather around the lit jyoti next to cutouts of Raja Bhoj and Vangdevi, all secured in a transparent case with seven locks and guarded by an armed policeman.

According to Choudhary, for a movement to last decades, it must become part of society’s religious and cultural fabric. To this end, the Bhoj Utsav Samiti organises programmes like Vedaram Sanskram, where parents bring infants and toddlers to be blessed inside the Bhojshala on Tuesdays, explains Kisan Diwedi, 27, a BCom graduate in charge of several sub-groups, including one where his task is to mobilise youths.

‘A fabricated book of lies’

Meanwhile, Dhar’s Muslim community, comprising about 25,000 of the city’s 1.5 lakh population, is busy with Muharram preparations, which will continue for 10 days. Seher Kazi and Waqar Siddiqui are busy coordinating with police for the procession as news of vehicles being stopped comes in.

Amid frequent calls, Siddiqui dismisses the ASI survey as “a fabricated book of lies”. “The room where they found idols was used by the ASI as storage for idols from all over Dhar,” he says.

Siddiqui also alleges that the ASI violated the Supreme Court’s directive by damaging the structure’s basic elements. “They deliberately broke two slabs and other evidence that points to it being a mosque. They are working in cahoots with the petitioners,” he said.

The Muslim community invited BJP MLA Neena Verma to participate in the Muharram procession, but she declined, citing commitments in Bhopal. Hindu Mahasabha member Gopal Sharma, who had even accompanied the ASI team during the survey, claims MLA Verma has not offered prayers at the Bhojshala to date and maintains equal distance from both communities.

Sharma, former Bajrang Dal’s Dhar convenor, criticises both BJP and Congress. He accuses the Digvijay Singh government of imprisoning Mahasabha members and claims that while the BJP under Uma Bharti came to power in 2003 riding the Bhojshala wave—even making a promise in its election manifesto—subsequent BJP governments have kept their distance.

“We had a saying that with a new government, only officers would change but the sticks would remain the same. But under Shivraj Singh Chouhan, the officers also changed and the sticks also became thicker. We weren’t only booked but also thrashed,” says Sharma, who has been imprisoned 19 times on various charges, including attempt to murder, and even declared a fugitive once.

On whether the Bhojshala issue will resonate nationally like the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, Sharma says one has to wait and watch.

“When there is honey, bees will always come. Our fight isn’t political but cultural, though politicians are smart enough to reap benefits when possible,” he says.

Laying the groundwork

Twenty years ago, the area around the complex was a bustling marketplace with butcher shops, a cattle market, and a cinema hall. As the “liberation” of Bhojshala gained traction, these businesses shut down one by one. The cinema’s ticket counter is now a police checkpoint restricting entry to the complex. The constant curfews have pushed traders away from Dhar’s colourful melas, which once attracted villagers and tribals but subsequently was reduced to a trickle.

“It used to be a place of trade and funfair. Neither Hindus nor Muslims fought over prayers inside the Bhojshala complex. People who came for the cinema parked their bicycles across the ground. Now there are only barricades everywhere,” says Satilal, a maintenance worker at the district’s Public Health Engineering Department who sells eggs on the side.

Author and journalist Rashid Kidwai says it was the BJP under Uma Bharti that raised the Bhojshala issue before the 2003 Assembly election but their victory was not due to Bhojshala but a strong sentiment of change agains the incumbent Digvijaya Singh-led Congress government.

“The simmering issue of Bhojshala and the Kamal Maulana shrine looks like a fascinating replay of Babri Masjid or Gyanvapi. But it never became a poll issue that could resonate with the people,” Kidwai said.

But tensions have always simmered, especially since the ASI took over the complex in 1952. The period from 1990 to 2003 was the most violent, culminating in the ASI’s April 2003 order allowing Hindus access on Basant Panchami.

Gopal Sharma traces the struggle back to 1935, citing his father Ganesh Datta Sharma’s involvement with the Hindu Mahasabha.

“We are four brothers, and I had got a job in the police service, but my father said if all his sons took jobs, we would lose the fight for Bhojshala. Since then, it has been my life’s mission to secure the title deed for Hindus,” Sharma says.

Away from the bustle of the Muharram procession, Ashish Goyal, a key figure in sustaining the issue, admits the Ayodhya verdict motivated him to “truly lay the groundwork” for his petition. In 2000, he left ABVP to become the Dhar convenor of the Hindu Jagran Manch. He has been central to organising pro-Bhojshala events since 1996, including bringing in prominent Hindu nationalist leaders.

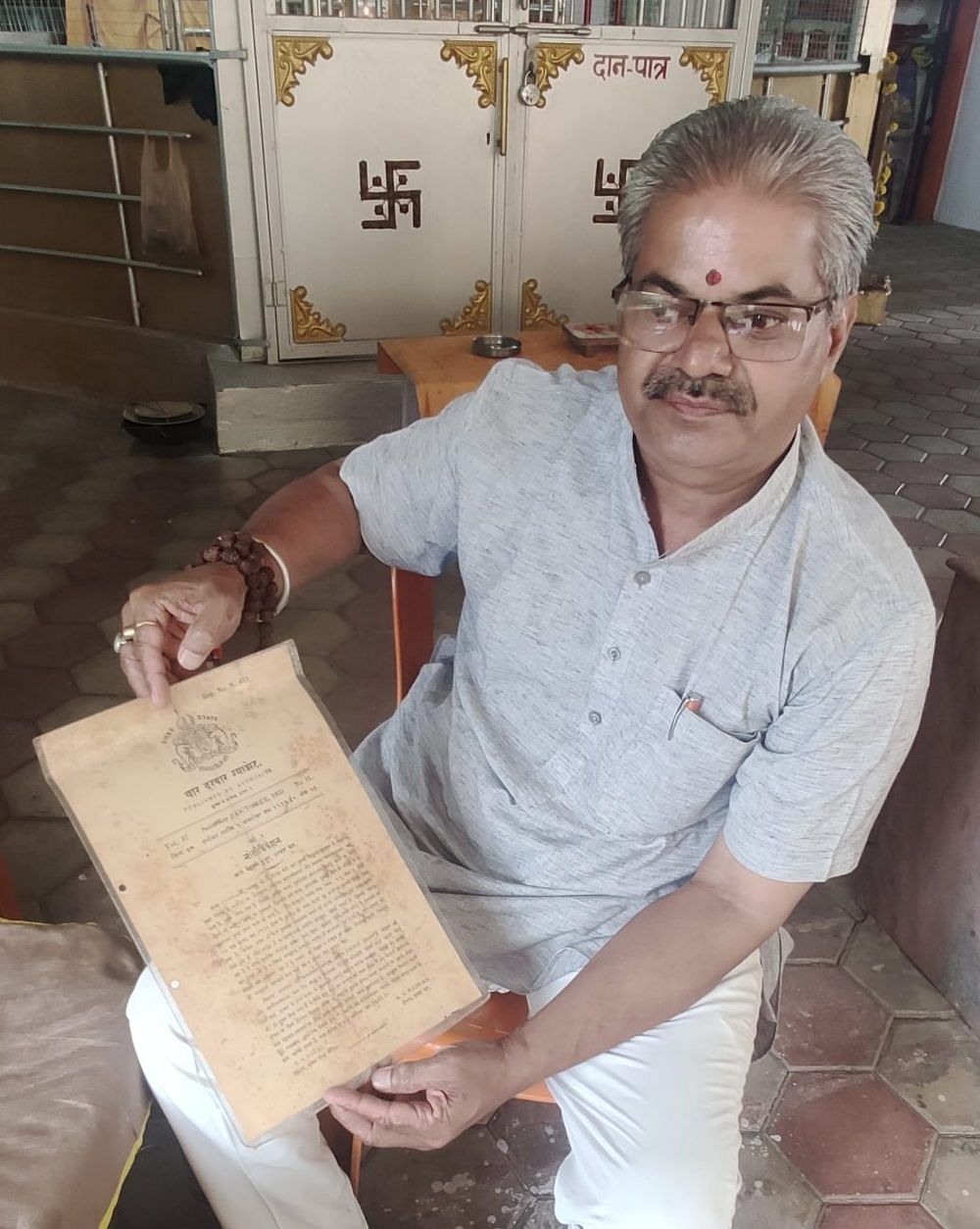

Goyal and Sharma reached out to the Lucknow-based Hindu Front for Justice. For ‘research’, he dug up land records, and contacted royal family descendants before filing their petition in May 2021.

“We had five demands in our petition, the two most important being that the entire Bhojshala complex be handed to Hindus, with the namaz completely banned there. We also want the idol of Maa Vagdevi to be brought back from London,” Goyal explains.

“Our petition had five demands, the two most important being that the entire complex be handed to Hindus, banning namaz there, and that the idol of Maa Vagdevi be brought back from London,” Goyal explains.

The Hindu Front for Justice group claims that the mosque was constructed between the 13th and 14th centuries during Alauddin Khilji’s reign by “destroying and dismantling ancient structures of previously constructed Hindu temples”. In March 2024 the high court directed the ASI to conduct a scientific survey of the complex to “demystify” its nature. In April, the Supreme Court refused to stay the March 11 high court order, but instructed against carrying out any physical excavation that would alter the character of the complex. It also ordered that no further action be taken on the outcome of the excavation without its permission. The next high court hearing is on 22 July.

Fear around the corner

Dhar’s Superintendent of Police, Manoj Singh, emphasises the importance of community policing in maintaining peace. “Constant interaction with everyone, from prominent community members to shop owners and students, has helped win trust,” he says. The authorities have implemented extensive security measures, including additional CCTV cameras to supplement those installed by ASI at the Bhojshala complex. Police units are permanently stationed at three locations around the Bhojshala-Kamal Maula Mosque complex, while drones monitor houses and high-rises to prevent potential disturbances. For the Muharram procession, 245 police personnel from eight stations were deployed in Dhar city, with senior officers patrolling the area. Similar arrangements are planned for the day of the court hearing.

Goyal can’t hear the Muharram procession from his showroom as it passes through Hindu-dominated Subhas Marg, about 700 metres away from Bhojshala. The men call out to the Hindu residents peeping through their shops and balconies of their homes, before stopping in front of a house. Sobha Malviya, 50, quickly steps out with her grandchildren and walks twice under the tajiya—a miniature replica of the tomb of Imam Hussain.

“It is a ritual followed by Hindus who pass under the tajiya believing it wards off evil and grants good health. It is their gods much like our Mata Rani,” she says. However, like many of her neighbours, she is worried the fragile peace is about to end.

“We have heard the courts will decide on it,” she says before returning to her chores.

(Edited by Prashant)