Gurugram: Agam Khare lifts a coarse, brown sheet resting on the table. It looks and feels like leather—the kind used in handbags, shoes, car seats, saddles, wallets, and luggage. But this leather hasn’t been cut from an animal hide. Nor is it a plastic or plant-based imitation.

This ‘bio leather’ is part of a biotechnology revolution on the cusp of disrupting everything from agriculture to luxury brands. Instead of harvesting from nature, scientists are recreating its molecular blueprints.

“We grow it. We literally mimic how the animal skin is built through biology and make this leather,” said Khare, the 35-year-old founder of Absolute, a biotechnology company now launching products after years of research. “It’s not synthetic because zero chemistry has gone into it.”

To make the bio-leather, selected microbial cultures are fed in a controlled lab environment until they form thick sheets. These sheets are then treated and finished, much like tanning, to behave just like animal leather.

At its core, Absolute is a deep biology company exploring how nature engineers its outcomes. How does one apple on a tree end up larger, sweeter or deeper in colour than another? For farmers, this translates into yield, quality and therefore income. And if biology can code an apple, why not the quality of leather?

The answers to these questions are literally placed on the table at Khare’s office in Gurugram.

Khare is targeting three areas to implement his groundbreaking research: agriculture, proteins and longevity, and materials. Over 50,000 nature-based ingredients— bacteria, fungi and botanical extracts collected from sites across the globe—sit in a database, which his team uses to study and test combinations to create products ranging from biofertilisers to whey protein.

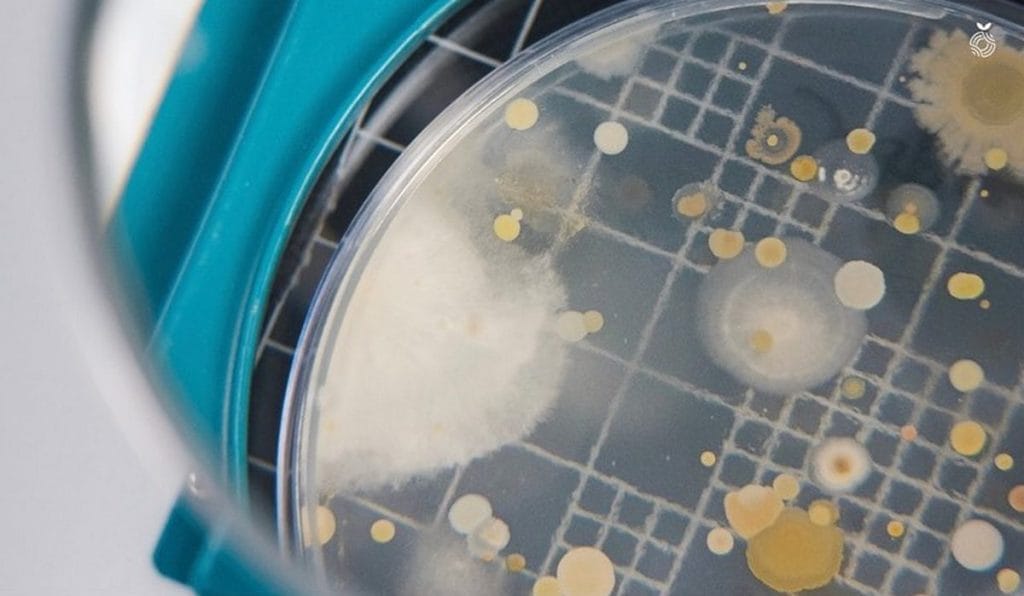

Experiments are running in full swing in the lab behind the office. Multi-coloured petri dishes rest on a table, one of them testing mould resistance. Another table has a group of plants growing in paper cups, each treated with one or more organic ingredients. Some have grown taller than the lone, control plant at the front.

There are two rules we laid down on day zero. The first is that performance is as important or greater than sustainability. The second is that economics is greater than genomics

-Agam Khare, CEO and founder of Absolute

With investors seeing results, the funding is flowing in too. The ecosystem is catching up to recognising the importance of biotechnology. Investors spent four months just studying Absolute’s intellectual property, valuing it at close to half a billion dollars. In 2022, the company raised $100 million from top venture capital firms including Sequoia Capital (now Peak XV Partners), Alpha Wave, and Tiger Global.

The Government of India’s Department of Biotechnology (DBT) is giving the policy fuel in fostering innovation in the space. The BioE3 (Biotechnology for Economy, Environment, and Employment) policy, launched in 2024, is prioritising the ‘industrialisation of biology’ in areas such as climate change mitigation, food security, and human health.

“Our role is to make a convergence of all the activities in this space so that they work together,” said Rajesh S Gokhale, secretary for the Department of Biotechnology. “Startups, large companies, innovation hubs, research institutions — all of these cannot operate separately.”

India could also be seeing more breakthroughs through its Rs 1 lakh crore Research Development and Innovation Fund (RDIF), set up to encourage the private sector to conduct cutting-edge research.

“When I look at the country today, I don’t see many players who are very deep into R&D,” said Khare, adding that it took Absolute ten years to complete trials, research, and regulatory approvals. “Also, because the ecosystem had no investors who would be willing to support it. A lot will change because of the RDIF fund.”

Also Read: Indian video games finally bring mythology into storyline. Taking it to AAA level

Building nature’s factories in a lab

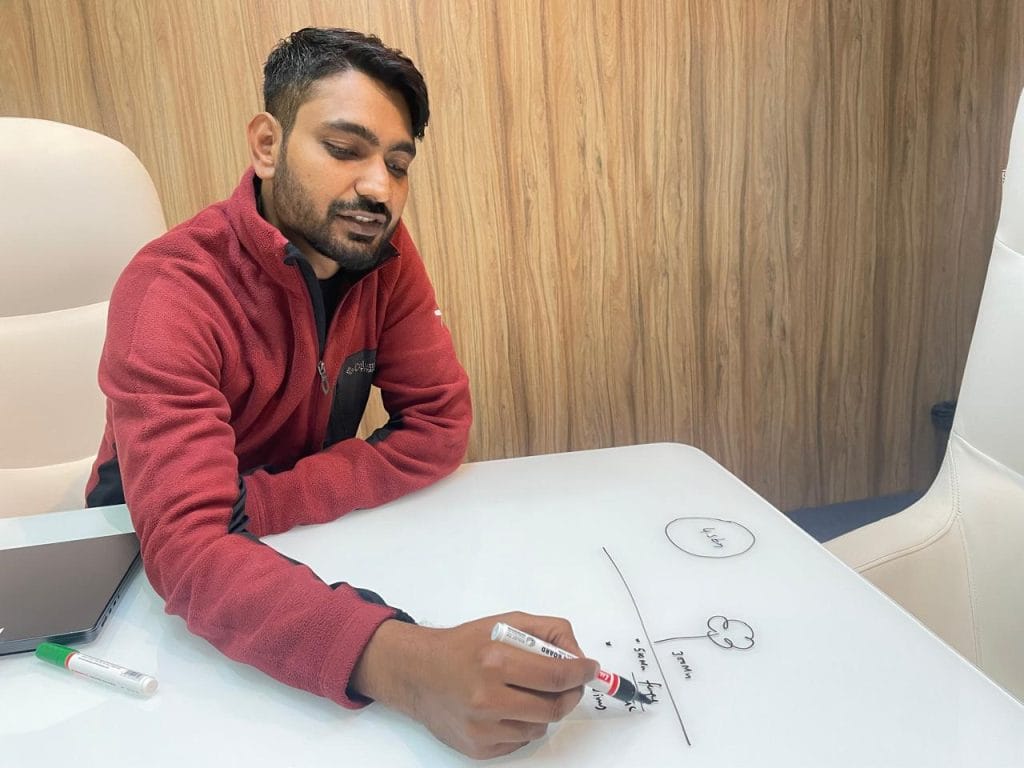

Khare has perfected explaining the science behind his company, helped by years of research and pitching to investors. He takes out a black marker, uses the whiteboard table as his canvas, and breaks down the company’s engine: the Nature Intelligence Platform (NIP).

“In our world there are a lot of extreme sites, like volcanic zones, glaciers, mangroves, seas, forests, deserts,” said Khare, drawing a box for each. “We go to these sites, collect samples, and decode them.”

His team has travelled to places from the Arctic to the Ganga River basin for samples of botanical extracts, microbial life forms (bacteria, fungi), proteins, peptides, enzymes, and even genetic material such as RNA. This toolbox of biology is then entered into the NIP and studied.

“We look at their traits, what they’re compatible with, or what they work against,” said Dr Prashant Khare, the company’s chief science officer. Some extracts show antibiotic properties or pest-control signatures. Others improve fertiliser-use efficiency or stimulate plant growth.

Today, the NIP has a collection of 50,000 unique, nature-based ingredients. Only 35 of these have been translated into products— reflecting the amount of trial and error, rigorous research, and quality checks that biotechnology demands.

Khare explains how these inputs ‘manifest’ into products with the patience of a teacher—a trait he says he likely got from his mother, a teacher.

“Your gut has trillions of microbes living in it. Every enzyme secreted in your gut is happening because a certain microbe feels that it should secrete it in a certain way,” he said.

Plants, too, have microbiomes. They are surrounded by bacteria, fungi, and yeast that protect them from pests, help absorb nutrients, and influence growth, colour, and yield. Instead of big machines, nature uses billions of these microscopic workers.

Absolute has taken a cue from this. Using bacteria, yeast, and fungi as microscopic factories and recreating the conditions they operate in, the company guides biological processes across use cases. Once a microbe’s function is identified, the team makes light edits to its genetic structure.

“We have deep expertise in genetic editing,” said Prashant, as he gave a tour of the lab. “We enable it to give the output that we essentially need.”

These outputs range from pesticides to protein products to leather.

The big market breakthrough

A corner of the conference room is stacked with a slew of agricultural products— biopesticides, biostimulants, biofertilisers. This is where the company’s science has gone to market first, under the brand name Inera

“We use nature’s wisdom to create alternatives to harmful chemical pesticides, which go into the food that you consume,” said Khare, grasping a packet of biofertiliser. “One bold mission we have is, how do you replace all this chemistry with biology?”

Khare isn’t under the false impression that his bio products are the first to hit the shelves. But to him, companies hid behind the ‘sustainability’ label as an excuse for not performing as well as their chemical counterparts.

Tomorrow, a geopolitical shift could happen and the supply can stop. The other big thesis in our company is how do you solve for China plus one?

-Agam Khare

“There are two rules we laid down on day zero. The first is that performance is as important or greater than sustainability,” said Khare, speaking with the conviction of an experienced founder. “The second is that economics is greater than genomics.”

The company conducted nearly three lakh experiments on the agriculture side, ultimately yielding only 11 products. Most just didn’t make economic sense. But for the ones that did, Absolute has pocketed $15 to $20 million in revenue since the products were launched 15 months ago.

Teams of Absolute’s scientists met with different farmer groups to demonstrate efficacy.

“And when they saw, they believed,” said Khare, adding that some of the world’s top agchem (agricultural chemical) companies have signed on to take these products global.

A nationalistic agenda

When Khare explains why Absolute exists, his scientific precision converges with patriotic expansiveness. He talks about India’s unsustainable subsidy spend, lack of homegrown intellectual property, and the urgency of competing with China. Sustainability is just one aspect of his mission.

“Biofertilisers can’t replace chemical fertilisers, but they can significantly reduce the current load of urea, DAP, MOP [types of fertilisers]” he said, his gaze contemplative. “The government is spending billions of dollars subsidising these. How long can we continue to do that?”

His other gripe is that IP isn’t being built in India. The current crop of pesticide companies — Bayer (Germany), Corteva (US), FMC (US) — all have a presence in India, but the ‘IP value is sitting outside’.

Self-reliance, to him, is an economic necessity.

“Tomorrow, a geopolitical shift could happen and the supply can stop,” he said. “The other big thesis in our company is how do you solve for China plus one?”

Khare wants to take China head-on. Right now, he said, it’s beating not just India but the rest of the world with its science and low production costs. His ambition is to build an alternative, at least in agriculture, the health space, and materials.

The protein frontier

Whey protein is a starting point.

India imports most of its sports-grade whey protein from the US, UK, and European countries to meet demand due to a shortage of domestically produced concentrates and isolates.

“Look at the whey protein situation. In India, we make a little bit of whey, but we are mostly importing it and are dependent on Europe,” said Khare. “Today, we [Absolute] have commercially synthesised whey protein in India.”

He went on to make some bold claims, including that Absolute was one of only two or three companies in the world with this capability. Not just this, he asserted that his protein production was cheaper than any Chinese company.

The protein products are in pre-launch, with the company only recently starting commercialisation. But Khare added that the company already has over $30 million of LOI (letter of intent).

The market opportunity for fermentation-derived proteins is there for the taking. It’s expected to be well over $100 billion by 2034. And whey protein is only one class of protein that Absolute is working on. The other two are an anti-inflammatory enzyme and a replacement for sugar.

“It’s a protein that tastes exactly like sugar and can replace sugar. And for every 1,000 kilograms of sugar, you need 1 kilogram of this protein,” said Khare, adding that there has already been early demand from pharma companies.

Bio-leather to ‘take on the world’

He is also revolutionising the way leather will be made and luxury products produced in future. Not from animals or chemicals, but through microbial fermentation.

In the materials category, this is something that looks and behaves like the real thing, but exists in a class of its own. Khare glanced at the sheet on the table.

“We haven’t coined a term for it yet. We still call it bio leather,” he said with a smirk.

Khare hasn’t started commercialising it (“not our priority right now”), but early experiments have yielded impressive results. He picked up a ‘snakeskin’ shoe. Every part of it – including the sole, except the laces – has been grown in-house from scratch.

“You see three classes of companies on the leather side: animal-based leather, PU and PVC (plastic) leather, and plant-based leather, where companies use papaya, pineapple, banana, or cactus skin to make leather,” said Khare, holding his product in his hand like a newborn child.

Many of these alternatives, Khare argued, don’t stand the test of time, unlike animal-based leather that can withstand wind, heat, and cold. Absolute has mimicked how animal skin is built, using biological processes.

Global luxury brands have already shown an interest in his bio leather product, he said.

“Leather is a $400 billion market globally,” he added. “Today, India is building massive positions of advantage, where one single product can take on the world.”

Also Read: Can monkeys teach ‘dumb’ robots? Bengaluru’s CynLr & IISc lab are making automation smarter

Tier-3 to ‘third wave’ science

Before pushing the boundaries of bioscience, Khare was a small-town boy who grew up in Khetri Nagar, Rajasthan. Water ran for barely 20 minutes every few days in the tier-3 town, a scarcity that first stirred his interest in science and sustainability.

“Some of my friends from regions around Jaisalmer would dig pits during the monsoons and collect the water,” said Khare, adding that growing up in this environment created a sense of community and a thirst to tackle problems.

His father, who worked at a factory, would bring back books, while his mother, a teacher, put a premium on learning.

He remembered looking up at the stars as a child, awed by their number.

“If you uncoil the genes—the DNA—in your own body, you could go to Pluto and back 17 times,” he said, smiling.

For Khare, decoding biology is the “third wave” of transformative science. The first was physics, which electrified cities and gave us telecommunications; the second was chemistry, which created modern medicine and food. AI, to him, is just a tool that speeds up the process.

The investing community needs to be aware of how to invest in deep R&D based companies. These companies aren’t going to be making revenue in year one, three, or five. It will be in year six or seven, so there is a cycle

-Agam Khare

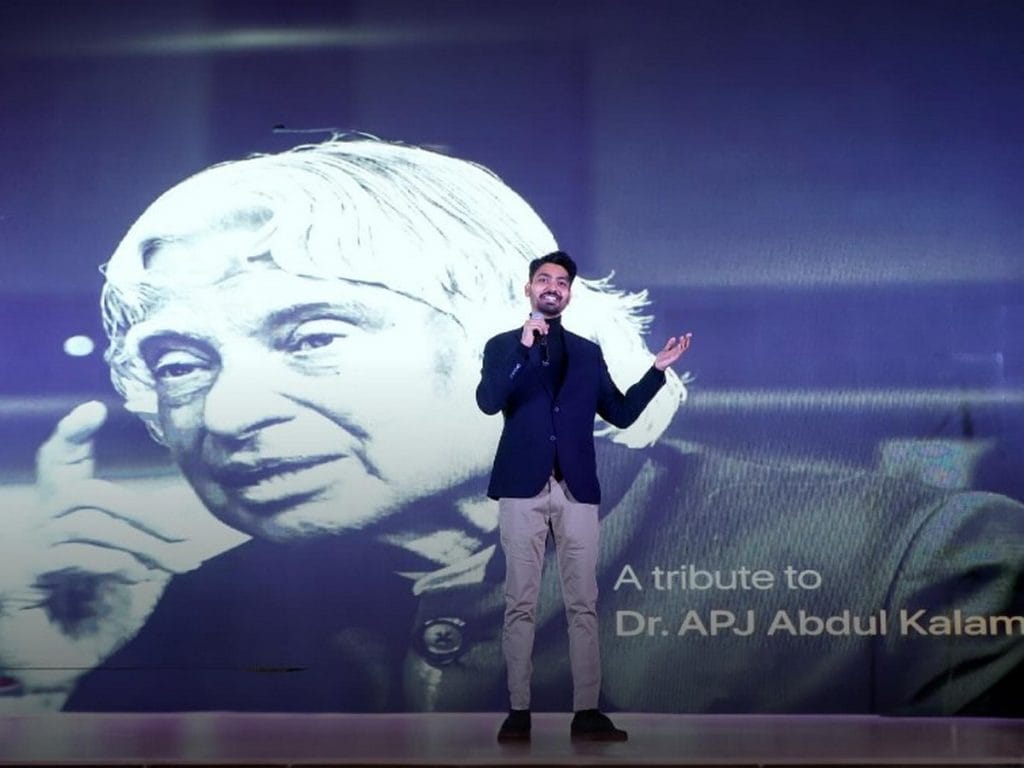

Absolute has a storied lineage. Khare said scientist and former President of India Dr Abdul Kalam gave the company its name. Back then, Khare was part of a team working on emerging technologies at the Kalam Foundation.

Founding Absolute was, in many ways, a tribute to the late president’s mission. When Kalam died in 2015, Khare was deeply affected.

“He always asked me what the grandest challenges were that the world faces,” Khare recounts. “And what I would do in my life to pick up on his mission.”

But before founding the company, Khare worked in industrial robotics at Vertex Group, a factory automation company, from 2012 to 2016.

“We built robot arms for factories where humans can’t operate because of the high temperatures,” he said, as he walked through the disinfectant chamber of his lab.

Today, Absolute employs around 300 people, half of them in R&D and technology. Of its 80-85 scientists, nearly 30 have PhDs. But breakthrough innovation is a slow game. Despite starting in 2015, Absolute’s agricultural products reached the market only 15 months ago.

“There is very little capital in India for startups to set up capex,” he said. “For setting up an EV factory, there is a pathway people are accustomed to. For new innovations, there isn’t.”

The government’s Research Development and Innovation Fund (RDIF) is a “game-changer”, according to him.

“But for RDIF to succeed, the investing community needs to be aware of how to invest in deep R&D based companies,” said Khare. “These companies aren’t going to be making revenue in year one, three, or five. It will be in year six or seven, so there is a cycle.”

Unlike traditional businesses, those built around groundbreaking innovations are exponential in nature and can capture the entire market with a product. Like Absolute’s bio leather.

Khare picked up the brown, square piece again. He is itching to launch it, but for now, he is prioritising agriculture and proteins.

The impact, he said, is already visible. He recalled asking a farmer in Sonipat why he was using their biological products.

“He said something which stayed with me forever,” added Khare. “He told me mitti toh meri hai, zeher kaise daal doon (the soil is mine, how can I put poison in it).”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Perpetual cribbers like you with a defeatist mindset are the ones who are actually restricting India’s capability.

India’s capability is restricted to snake oil and snake skin.