Srinagar: Kashmir has a secret buried underground. It is one of the largest complexes of stupas. And archaeological circles in the valley are abuzz, waiting to unearth the region’s most significant dive into its ancient past — one that could link it to the Fourth Buddhist Council.

The first evidence of this Buddhist site was found thousands of miles away — in France—when a senior archaeologist, Mohammad Ajmal Shah, stumbled upon a grainy, faded photograph of three stupas from Baramulla, tucked away in an archive at Guimet Museum in Paris.

“It was one of the happiest moments of my life. I was on a fellowship in France when I visited an archive and came across this photograph. As an archaeologist, the moment marked the beginning of a new discovery into Kashmir’s lesser-known archaeological past,” said Shah, who was on a teaching fellowship in France in October 2023.

Kashmir is slowly reclaiming its ancient history. It is being led by a small army of archaeologists from the Department of Central Asian Studies at Kashmir University — where archaeology was introduced as a formal discipline only in 2017.

Archaeology in India’s only Muslim-majority state is now learning to dig deeper than and beyond Islam. From Buddhist stupas to the legacy of Kashmir’s first indigenous Hindu king Lalitaditya and ancient artefacts depicting practices such as sati and sacred springs (locally known as nags) at temples – these archaeologists are peeling layers of the region’s past, shifting the narrative beyond the Islamic period. The newly identified site in Baramulla is, according to Shah, among the “largest Buddhist complexes” in the Himalayan region that is now being linked to the Fourth Buddhist Council by archaeologists. This could mark a significant breakthrough in understanding Buddhism’s roots in the valley. And the Directorate of Archives, Archaeology and Museums has joined hands with Kashmir University.

Jammu, too, is drawing renewed focus to the ancient Buddhist site of Ambaran, situated along the banks of the Chenab River. The site was first excavated over 25 years ago by BR Mani, former Director-General of the National Museum.

It was one of the happiest moments of my life. I was on a fellowship in France when I visited an archive and came across this photograph. As an archaeologist, the moment marked the beginning of a new discovery into Kashmir’s lesser-known archaeological past – Mohammad Ajmal Shah, archaeologist

“There’s a common understanding in Kashmir that history began with the Islamic period and ended there,” Shah said. “But there hasn’t been much concrete archaeological research into the ancient past. We’re now looking into that history of Kashmir — the cultures and religions that shaped it long before the present day.”

Search for Baramulla’s Buddhist site

Three large mounds rise from among wild grass and rice fields, with a meandering Jhelum River in the backdrop. Two of them lie on one side, with the third one separated by a narrow canal. Children climb up these grassy mounds on lazy afternoons, blissfully unaware of their historical significance. But to the archaeologists in Kashmir, these are stupas—structures that could reshape the Buddhist history of Kashmir.

Locating the site in 2022 was only the beginning. The real work — excavation – couldn’t begin without going through a maze of permissions from the archaeological department. But even before that, Shah and his team had to prove that the three stupas weren’t just an anomaly.

Returning from his month-long teaching fellowship in France, the first thing Mohammad Ajmal Shah did was visit this site in Baramulla. Alongside a 10-member team of archaeologists, he made over a dozen visits to the site. Each time, they spent nearly 10 hours combing through the area – examining every curve and crack of the stupas. Multiple surveys were conducted. Drones hovered above, capturing aerial imagery. The texture and composition of stones were studied closely to identify their nature.

After the preliminary research, Shah began compiling his findings—and started taking his work to academic conferences.

“The discovery of one of the largest Buddhist complexes having evidence of three Stupas and an apsidal hall along with other intriguing features of a site present a vivid picture of the thriving early historic (Kushan) Buddhist settlement on the outer periphery of the Baramulla district,” read Shah’s paper ‘New Investigations in Buddhist Archaeology of Kashmir: A Preliminary Survey.’

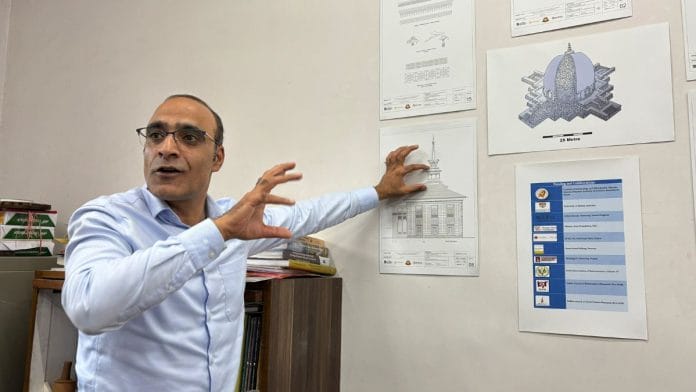

It was at one such conference—Vitasta 2024, held at the Sher-i-Kashmir International Conference Centre in Srinagar—where the signs of a greater interest in this strand of Kashmir’s history emerged. Leaning into the mic, Shah spoke about the potential Buddhist site in Baramulla. His words struck a chord with the newly appointed Director of Archives, Archaeology and Museums, Kuldeep Krishan Sidha, who was sitting among the audience and had also been trying to recover Kashmir’s ancient history. The very next day, Shah was in Sidha’s Srinagar office, presenting his findings. Soon after, an order was passed and funds for the excavation were sanctioned.

Two months from now, the site will undergo its first formal excavation. For Shah, it’s a milestone—one he believes could reshape the way this region understands its past and the way the world looks at Kashmir.

“These stupas were always here. But no one paid much attention,” Shah said, seated in his office at Kashmir University. He had himself visited the site in 2010 as a PhD scholar and was suspicious about it being a stupa.

For Shah and his team of archaeologists, unravelling the ancient past of Kashmir took more than just academic curiosity. It meant doing extensive groundwork—reading literature, hunting for references, visiting forgotten sites, and burning the midnight oil to piece together fragments of history.

Also read:

Stepping into new terrain

It was the Rajtarangini—the historical chronicle of Kashmir written by historian Kalhana in the 12th century—that led archaeologist Irfan Qayoom to the ancient sites in Kupwara’s Lolab Valley in 2022. Qayoom was intrigued by a passage that mentioned Raja Luv. According to the text, Luv had built what Kalhana described, perhaps apocryphally, as 84,000 stone structures in Lolab.

“The first thing I thought was that I should visit Lolab and see if there really are 84,000 stone buildings. I was sure I’d find something,” said Qayoom, who is currently pursuing a PhD on the legendary king Lalitaditya.

Lalitaditya Muktapida was a Karkota monarch of the Kashmir region who ruled during the 8th century. In Rajatarangini, Kalhana describes the king as a world conqueror. “But not much archaeological research has been done on him”, said Qayoom, who is trying to change that through his work.

The archaeologist began his fieldwork in 2022. Each morning, he would travel from Srinagar to Lolab, covering a 130-kilometre distance in two hours. He would meet residents, spend time with them to discover the folklore specific to the region, and ask if they had come across any unusual structures in the area.

“There hasn’t been much archaeological research on the ancient period here, so we’re starting from scratch. I would measure these sites. Check whether these sites were multi-cultural or single-cultural sites,” said Qayoom.

From inquiring about nags, temples, or unusually large stones to visiting these sites himself and starting all over again after setbacks—Qayoom set out every day until he found some sites of archaeological value.

“This is the first-ever census of these sites,” says Qayoom. While some of these locations have been mentioned in academic texts, he said, they were never explored on the ground until now.

His small cabin at Kashmir University is now filled with photographs of memorial stones, stupas, and the routes once taken by King Lalitaditya. Qayoom belongs to the first batch of Kashmiri archaeology scholars diving into the ancient and early medieval periods of the region.

“Earlier, there were archaeologists from Kashmir, but barely a couple,” he said. “Now, with this department, archaeology is finally getting mainstream attention.”

Qayoom’s work on memorial stones featuring sati and kings and inscriptions in Sharda script – the ancient script of Kashmir — is no longer confined to the valley. He is now presenting papers such as Religions, Texts and Spaces: A Multidisciplinary and Multilingual Perspective at major conferences hosted by Kashmir University — in collaboration with the Indian Council of Philosophical Research (ICPR) and Russia’s Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography.

This site has to be discovered, rather. It is barely mentioned anywhere. There is no full-fledged literature on it. It is going to be a hot cake for all the research scholars – KK Sidha, Director, Directorate of Archives, Archaeology and Museums

And his research is taking him to temples and springs held sacred by Kashmiri Pandits – many of whom left the valley during the 1990-armed insurgency.

At Lavnag, Qayoom discovered three small Shiva temples and two springs. In Kashmir’s temple architecture, the presence of springs around the deities is a common feature. At another site, a monolithic rock Satbaran – a trefoil arch – was found, which is a motif found in several temples of the early medieval area.

It was inside the niches – recesses in the wall – where the main deities of Mother Goddesses (Ashtamatrikas) and Shiva were placed. According to Qayoom, Kalhan in Rajatarangini mentions that the Matrika cult was very popular in Kashmir.

“And these Mother Goddesses were usually set up around a Shiva deity or shrine in Kashmir and in bordering areas near the main passes,” he said.

Qayoom’s PhD thesis will be on ‘The Rise of an Emperor: An Archaeo-Historical Study of King Lalitaditya Muktapida of Kashmir.’ What drove the scholar to choose Lalitaditya was his indigeneity and his fragmented history.

“Despite being one of the most celebrated figures in Kashmir’s literary tradition, the archaeological and historical record surrounding him remains fragmented,” said Qayoom. His research on Lalitaditya took him to the Martand temple associated with the king, and several other places in Kashmir sharing similar archaeological features.

“Lalitaditya reigned in the 8th century, which represents a critical juncture in Kashmir’s political authority, temple architecture and material culture. Yet there is limited archaeological verification,” Qayoom explained.

But it wasn’t just the nags, temples, and Buddhist sites that the archaeologists discovered. They have now stepped into a new and unexplored terrain—one that uncovers the regressive cultural practices of Kashmir’s past.

Also read:

J&K’s first excavation

The Directorate of Archives, Archaeology and Museums in Srinagar is brimming with local residents eager to meet Director KK Sidha. Word has spread: Sidha is here to protect monuments and unearth the region’s lesser-known past. From the family members of the famed 20th-century poet Mehjoor to a section of Sufi singers and Kashmiri Pandits – everyone is knocking at Sidha’s office door with applications, asking him to protect the heritage sites, shrines, and temples.

There hasn’t been much archaeological research on the ancient period here, so we’re starting from scratch. I would measure these sites. Check whether these sites were multi-cultural or single-cultural sites – Irfan Qayoom, archaeologist

Opposite Sidha sits archaeologist Shah, listing the tools required for the excavation—shovels and excavators, among other things.

“As this is Jammu and Kashmir’s first-ever excavation, the department doesn’t yet have the necessary tools,” said Sidha, encouraging archaeologists to bring forth their findings.

Shah and a team from the Directorate of Archaeology, Archives and Museums have already visited the site, Zehanpora in Baramulla district. Demarcations have been made. Soon, the area will be fenced off, and the first-ever historical dig will begin.

“Not only is this a first-ever excavation (in Jammu and Kashmir), it is also the first-ever convergence project. Our department has not only collaborated with Kashmir University but also ASI. We have written to them for their technical support,” said Sidha, who speaks sparingly and sits with a stern posture.

It was in December last year that Sidha was appointed Director of Archives, Archaeology and Museums. Since then, he has kept his team on their toes. Over the last month, a small team of half a dozen employees has been touring Jammu and Kashmir — visiting each district and inspecting protected monuments and heritage sites. Every night, they compile photographs and detailed reports of their visits and submit them to Sidha.

Sidha has opened the gates to archaeologists across Jammu and Kashmir. “I want archaeologists to come forward with their findings, and I’m open to working with them. There is an abundance of history in Jammu and Kashmir, and during my tenure, I want us to recover as much of it as we can,” he said.

“We will be marking the entire cross-section of this area. Each site will be divided into four quadrants — and those quadrants will offer a glimpse into the stupa,” he added.

This is not the only discovery. In Lolab, archaeologist Irfan Qayoom has recovered memorial stelae — commemorative stones — that point to the region’s Hindu past. According to Qayoom, this is the first-ever archaeological work on memorial stones in Kashmir. Until now, they had only been mentioned in the Rajtarangini, where they were referred to as “funeral stelae.”

It was his field survey in the Burnai region of the Lolab Valley in 2022 that led Qayoom and Shah to a remarkable find: eleven memorial stones (both inscribed and non-inscribed). According to Qayoom, these stones had received virtually no scholarly attention in Kashmir until now. As Qayoom, Shah, and another scholar, Vrushab Mahesh, began to study them, a forgotten world of ancient narratives began to emerge—stories of sati, heroism, and inscriptions written in the Sharda script.

This tradition of creating memorial stones has been dated back to the early Hindu period during the Karkota dynasty of Kashmir, says Qayoom.

One such memorial stone depicts a woman with raised arms, likely performing sati. The stones found in Kashmir portray women with raised hands, wearing bangles and holding lemons or bridal veils. But what truly sets them apart from other sati stones is the namaskaram pose—an expression archaeologists interpret as a gesture of piety, signifying both a devotion to the attainment of afterlife and loyalty to the husband.

Another memorial stone shows a man on horseback, armed with weapons like bows and arrows, highlighting the martial valour of the deceased. Most of these stones, however, were found broken or severely worn with time.

“These memorial stones give us a glimpse into the indigenous characteristics of Kashmir’s past—often depicting singular or dual events rather than multiple scenes,” said Qayoom. “The practice of erecting such stones has roots in the early historic period. But today, this custom is no longer actively practised in Kashmir.”

Also read:

‘No literature on this site’

Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar and traveller Xuan Zang entered Kashmir through the Baramulla route during the 7th century. According to the archaeologists at Kashmir University, Zang’s travel to the valley was likely inspired by tales about Buddhist stupas and monasteries in the Baramulla region.

In Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records of the Western World by Hsüan-tsang, ca.596-664, and Samuel Beal, 1825-1889, there’s a clear account of Zang’s travels. Referring to the book, Shah said that Zang had come across several stupas during his travels.

“His description of entering Kashmir through stone gates and visiting a series of stupas closely resembles the features found at the Zehampora site,” he said.

During their groundwork at Zehampora, archaeologists found pieces of terracotta and Kushan-era pottery — primarily red ware — scattered across the site. According to Shah, this meant that the site belonged to the Kushan period.

“This site has to be discovered, rather. It is barely mentioned anywhere. There is no full-fledged literature on it. It is going to be a hot cake for all the research scholars,” said Sidha.

The Kushan period – spanning the 1st and 3rd centuries CE — marked the emergence of Buddhism in South Asia. The Kushans have been credited with spreading Buddhism across Central Asia and China. They also played a key role in the development and spread of Mahayana Buddhism as well as the Gandhara and Mathura schools of art.

“The presence of multiple stupas and other architectural features within a single archaeological site is unprecedented in the Kashmir Valley,” Shah’s paper read.

Qayoom, who is also working on the Zehampora site along with Shah, said that it has all the archaeological features found in other Buddhist sites of Kashmir – Harwan, Ushkur, and Parihaspora. But what sets it apart is its huge size.

This, he said, made them revisit the works of other archaeologists involved in discovering Buddhist council sites. The third Buddhist council of the Mauryan period, which was eventually unearthed in Bihar, featured a massive hall with 80 pillars. According to some historical sources, Mauryan Emperor Ashoka likely convened the third Buddhist council there.

Archaeologists have argued that the fourth Buddhist council was held in either Kashmir or present-day Pakistan. But no site discovered so far at these places has exhibited the scale or features required to host such a large congregation.

“But Zehampora can be that site. It can be the fourth Buddhist council. And can become the important Buddhist pilgrimage sites in Kashmir valley,” said Shah said as he proudly opened the book with his paper: New Investigations in Buddhist Archaeology of Kashmir: A Preliminary Research.

This article has been updated to reflect corrections and new information.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

Ironic that your writer should ask if Kashmir’ history begins with Islam- how accommodative and liberal!