Bengaluru, Gurugram: Each evening, a retired IAS officer in his late 70s packs a small bag, tucks in his passport and a handmade “boarding pass,” and announces, “I have a flight tonight.” The security guard checks his ID, offers him a seat in the lounge, and brings him a coffee. Minutes later, the dementia patient wanders back to his room at Frida Epoch Elder Care in Gurugram — and repeats the ritual the next morning.

Dementia couldn’t take away his discipline and his identity–only the reason for it.

Such repeated rituals are the face of daily struggle at the centre. In another room, a retired Hindi teacher arrives for day care, ready to teach with her notebook. Caregivers become her students as she writes, corrects, and signs her “pay slip” in a mock ledger before leaving, satisfied that another school day is done.

As India grows older, a hushed epidemic is creeping across the country—one that steals memories, identities, and leaves families in torment–and at times, violence. Longer life expectancy, chronic lifestyle diseases, social isolation, and the unravelling of traditional family structures are producing a full-blown dementia crisis among Indians.

Health and nursing attendants are not trained to care for people with dementia. And family members are clueless in handling the elderly slipping away into a twilight zone. And there aren’t enough public conversations and support groups.

Culturally trained to take care of ageing parents at home, many Indian families are drowning in guilt. But such care facilities and help are too minuscule to matter.

India’s senior population now rivals Japan’s—long regarded as a model for ageing preparedness and dementia care. Countries like Germany and South Korea began investing in specialised facilities, caregiver support, and research-driven prevention in the 2000s.

This incessant fight to keep the minds and memories from fading away, to cling to existence itself, is afflicting over 8.8 million Indians aged 60 and above, and is expected to engulf nearly 17 million by 2036.

Yet dementia lacks a national policy or meaningful presence in public health programmes. As family structures shrink, nuclear families are waking up to a crisis—ageing parents in distant cities, lost in familiar streets, and forgetting the names of those they love. Unprepared and emotionally stretched, the family members, often women, have become the untrained, frontline caregivers.

Some families with means turn to dementia care homes, where trained staff offer safety, structure, and compassion.

These facilities—few in number and very expensive—are largely confined to urban areas. Fewer than 50 specialised dementia care centres exist nationwide, most in big cities and run by private hospitals or nonprofits. Millions of families and elders in rural and semi-urban India continue to struggle alone.

To further compound the challenge, early signs of dementia are brushed off as quirks of old age, which delays diagnosis.

“We need to integrate across specialties. A dementia patient with hearing loss and diabetes won’t benefit if their ENT and endocrinologist never communicate about dementia. Our healthcare system isn’t set up for that,” said Manveen Kaur, Research Scientist and PhD fellow at NIHR Global Health Research Center for Multiple Long-term Conditions.

“We need policies that start dementia care at the primary level—train doctors to screen, manage multiple conditions together, and create referral pathways to reduce the risk of full-blown dementia.”

Family, duty, grief

Behind every dementia diagnosis, a family is struggling to rearrange itself as complete incomprehension clouds desperate conversations. Routines change, roles shift, and homes become exhausted care units.

Across India, helpless families are learning—often painfully—that caregiving is a long, intimate journey testing patience, empathy, and endurance in ways few are prepared for. And with it comes the heartbreaking realisation that dementia can’t be cured.

Renu Sachdeva’s mother-in-law, Surjit, was diagnosed with early-stage dementia at the age of 72.

“She was visiting us in Mumbai and would get confused about her way to familiar places. She’d say, ‘Can you remind me of the way again?’ So we gave her a small tag to carry with her with our address and contact details in case she got lost,” said Sachdeva, Life Coach & Counselling Psychologist, Founder Member, Dementia India Alliance.

As days passed, Surjit began to lose track of everyday things—whether she’d taken her medicine, had her tea, or turned off the stove.

After a 10-day physiotherapy course, Sachdeva recalled her mother-in-law saying. “Physiotherapy karani padegi, bahut dard ho raha hai (I need physiotherapy; the pain is too much).”

It was after the physiotherapy incident that she realised her mother-in-law could no longer manage alone in her Delhi apartment. She moved her to Gurgaon to care for her—and that’s when her caregiver journey began in 2018.

When Sachdeva realised she could no longer manage her mother-in-law’s care alone, she hired a 24/7 professional. But the mother-in-law didn’t like the idea of a constant companion. Sachdeva then enrolled her at the Epoch Dementia Daycare Centre in Gurugram, where she continues to go.

Finding the right caregiver was difficult. Dementia care requires constant engagement.

“As dementia cases increase, the need for skilled and compassionate caregivers is more urgent than ever. Yet even with trained caregivers, the reality is that India’s healthcare system is still ill-equipped to handle this mounting crisis,” Sachdeva said.

For many, caregiving becomes both a duty and an identity. Sharanya Munsi was only 17 when her mother, Sanchita—a history teacher—was diagnosed with early-onset dementia after a sudden stroke-like episode caused by cerebral vasculitis.

Though Sanchita remains physically capable, she needs guidance. Munsi built a structure around her mother’s days: a medicine box labelled by week, a smartwatch to keep track of time, and diaries for daily notes. To simplify finances, she managed everything online.

“The hardest part for me was watching a part of her confidence fade,” Munsi said. “She’s always been such a strong, self-assured woman. At some point, you realise that your parents are no longer your support pillars—you have to be theirs.”

A pet dog, Dio, became part of that structure.

“If I leave for work while she’s asleep, she’ll sleep till afternoon,” Munsi said. “So I wake her up and remind her that she needs to feed Dio.”

For young caregivers like her, maturity comes abruptly.

Abhik Mitra, 30, from Kolkata, is dealing with a similar crisis. His 56-year-old mother began forgetting how to cook, misplacing money and jewelry, and was unable to do simple tasks. One day, she urinated on a plate. It scared the family. Without wasting a moment, they rushed her to a doctor.

The family tried everything—medication, homeopathy, Ayurveda—but the decline continued. Mitra’s father, once uninvolved in household chores, now does everything: cooking, cleaning, bathing his wife, and even removing fish bones for her.

“When a woman–the traditional caregiver — develops dementia, the entire structure of the family collapses,” Manveen Kaur said. “And women, by the way, are twice as likely to develop dementia as men at the same age. So your designated carer is also the one most likely to need care.”

Also read: Nobody’s fighting for the Delhi Ridge. Few even know where it begins and ends

Memory units

The dementia care infrastructure in India is underdeveloped, and time is running out for patients and their families.

A handful of organisations—ARDSI (1992), Nightingales Medical Trust (1998), and the Dementia India Alliance (2023)—have stepped into the breach, running memory clinics, caregiver training, counselling, and awareness programmes.

Several private senior living providers, including Antara Memory Care and Epoch Elder Care, have started creating facilities for people with dementia.

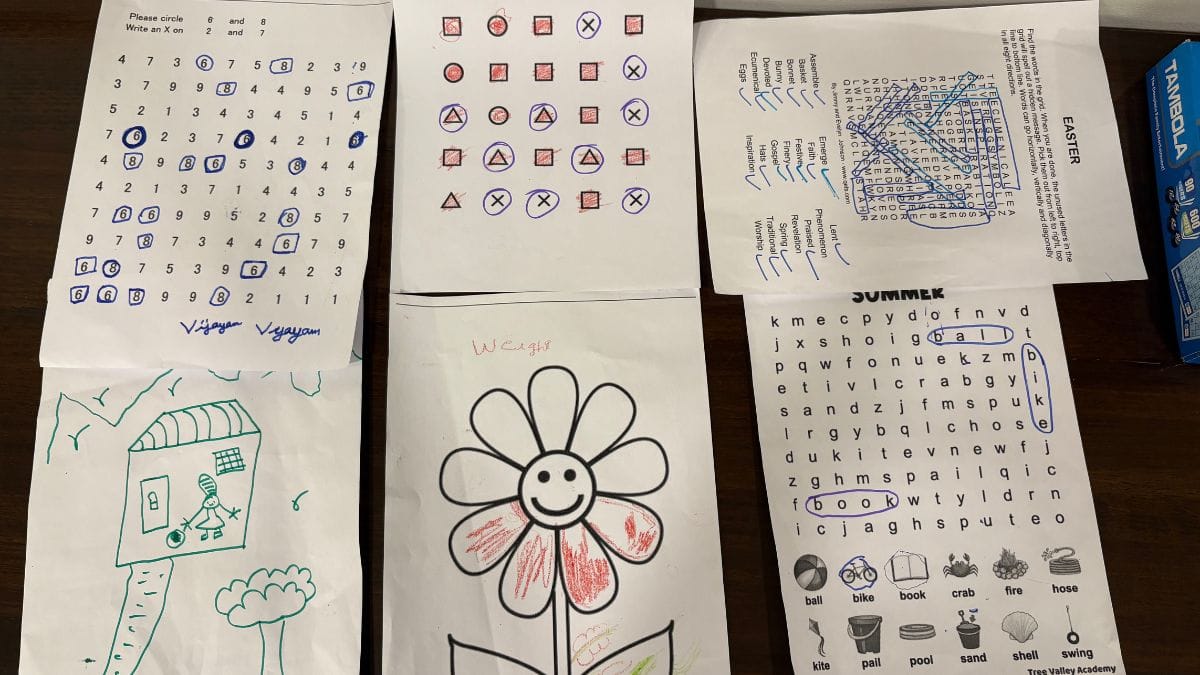

In these dedicated “memory units,” residents follow structured routines: music sessions, art and movement therapy, gardening, or simple household activities that help them stay engaged and calm.

“In India, large-scale institutional care is impractical, both financially and culturally. Families often cannot afford high-quality inpatient care, and socially, placing elderly relatives in care facilities is frowned upon. For most middle and low-income families, the solution has to be local, home-based, and community-supported,” said Manoj Kumar, psychiatrist and founder/clinical director of the Mental Health Action Trust (MHAT) in Kozhikode, Kerala.

He said that Daycare centres, even for one or two days a week, can give families a necessary break and provide supervised care. Basic skills for diagnosing dementia and managing medications can be taught to local doctors; it doesn’t require a dementia specialist. “Specialist care is scarce and will never be sufficient for India’s population.”

Everyday creativity and connections

A caregiver knelt before a male resident, in his late 70s, in a wheelchair, pointing to cartoon characters and asking him to name them. The man no longer spoke; words had abandoned him. Only a smile lingered on his face.

Dementia makes patients seem suspended in midair, untethered.

At Antara Memory Care in Gurugram, residents take part in activities crafted to stimulate the mind and support cognitive health.

Seven residents, all over 70, gather in the light-filled living area to talk, read newspapers, sing and take part in daily activities like puzzles, board games, crosswords, and occupational therapy. The centre has single and double hotel-style rooms, where, if needed, couples can live together; even families can stay for a few days depending on the resident’s condition. A psychiatrist visits every day to assess their condition, track dementia progression, plan engagement, and modify the care plan.

Daily routines and activities are structured to create a sense of familiarity and reduce confusion. One resident kept trying to go outside, insisting on going home. A caregiver came up with a clever trick: ‘Arey, how will you go without your purse? Go get it from your room first.’ When the lady went to fetch her purse, she completely forgot about leaving for home.

Across the city, Epoch Elder Care-Frida provides another window into life for seniors navigating memory loss.

At the entrance, a black stereo softly hums an old song—‘Ajeeb dastaan hai yeh, kahan shuru kahan khatam’ and an incense stick burns beside it. And in the common area, the wrinkled faces are lit up by the glow of television.

“Even the smallest role here needs training,” said Shashi Chauhan, a senior nurse who has been here for two and a half years. “Because in dementia care, one wrong tone, one impatient word can undo hours of calm.”

New caregivers assist seniors for weeks before they can be trusted. They’re taught the clinical signs of dementia, and have to manage medicine, meals, moods, memories, and moments of confusion. The security guard knows how to handle agitation.

Nurses are recruited through referrals or platforms like Naukri.com, while support staff, including care aides and housekeeping personnel, are sourced through third-party partners.

Dementia India Alliance has trained 7,289 caregivers through various programmes, including 3,589 healthcare professionals, 729 caregivers and 271 family members.

A network of support

Dementia care centres are also about slowing what cannot be stopped. Families often arrive expecting cures. “They think their parents will get better,” said senior nurse Shashi Chauhan. “We tell them dementia can’t be cured, but it can be slowed.”

That slowing happens through engagement—through constant stimulation and connection: music therapy, yoga, doll therapy, painting, tactile exercises. The goal isn’t to remember everything; it’s to remember something. Sometimes a song. Sometimes a smell.

As time passes, memory fades for everyone, whether in Gurugram or at Nightingale Medical Trust in Bengaluru. Rooms feel hollow even when occupied—residents lie with their faces turned toward the swaying trees outside their balconies, a world that no longer makes sense to them. What weighs most in the air is the obliviousness of what has been lost.

Nightingale is more affordable than most private dementia homes, where each resident usually has a dedicated caregiver. One caregiver here looks after four to five residents at night, which helps reduce costs.

“We’ve been working with senior citizens for over 15 years. Our focus is not just on severe memory issues or dementia; it’s on the full spectrum of behavioural and cognitive challenges that affect older adults. Wandering, agitation, and other behavioural changes can deeply affect families—emotionally, physically, and financially,” said S. Premkumar Raja is a co-founder of Nightingales Medical Trust (NMT), a non-profit organisation established in 1998.

Nightingale has been building a holistic dementia care network since 2006. It started with a single daycare centre, and by 2010, they had expanded to multiple residential facilities. Today, they run a 50-bed centre in Kolar and a 25-bed women-only dementia home in Kothanur, Bengaluru.

Each facility is designed to be accessible and affordable, reducing costs by about 35 per cent.

“Cost is always a challenge for us as an NGO,” Raja said. “We use technology–like sensors to monitor wandering, digital cognitive exercises, and care-management software—to enhance operational efficiency.”

Training the trainers

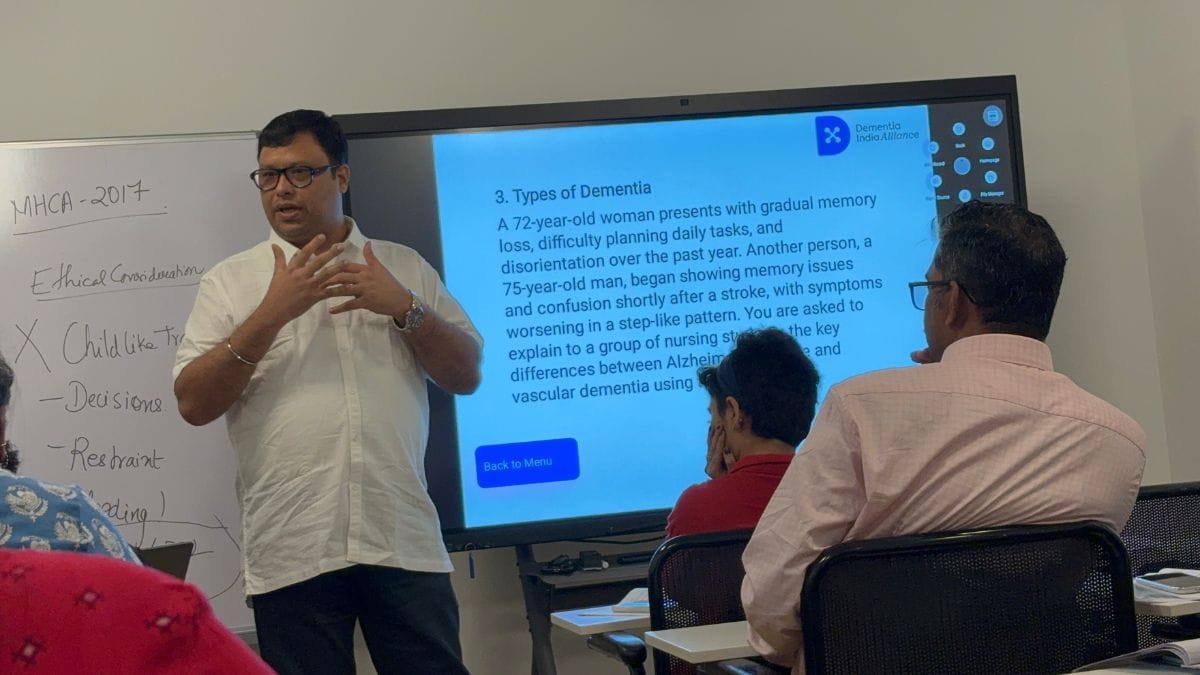

At the Dementia India Alliance office in Bengaluru, over 20 participants—ranging from young professionals and middle-aged psychologists and healthcare workers—engaged in a role-play exercise. Everyone took notes, learning to understand dementia and how to provide empathetic support.

“When spotting signs of dementia, it’s important to dig deeper. If someone gets lost, ask—was it at home, in the neighbourhood, or somewhere unfamiliar? For repeated questions or confusion, understanding context matters. These clarifying questions help distinguish normal ageing from dementia,” said Tripti Singh Balaji, founder of the elder-care app Anvayaa.

The session was part of Dementia India Alliance’s “Train the Trainers” programme, an initiative designed to expand dementia care across India. Conducted annually over three days, the programme combines theory, case studies, residential visits, and role-play exercises.

Expert faculty from organisations such as Nightingales Medical Trust and SCARF Demcares of Chennai bring real-world experience to the classroom.

The programme creates a ripple effect, as each trained professional spreads person-centered, culturally sensitive care across communities.

Bridging the dementia gap

Southern states like Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh are better prepared for dementia care than north India.

The Karnataka government has partnered with the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) and Dementia India Alliance to make dementia a public health priority. The State Dementia Action Plan, aligned with the WHO’s Global Dementia Action Plan, focuses on dementia screening, caregiver training, and creating dementia-friendly healthcare services.

Yet awareness alone cannot solve the crisis.

“Tackling dementia needs more focused and strategic efforts. Lessons learned from large-scale efforts made to address diseases such as polio and AIDS can be applied to fight dementia. For example, creating a dementia registry would help identify which states have a higher burden and require more attention,” said Rajit Mehta, Managing Director and CEO, Antara Senior Care. “We also need more geriatric specialists, psychologists, and neurologists to drive early diagnosis.”

Policy efforts are growing, but gaps persist. Research hubs like the Centre for Brain Research at Bengaluru’s Indian Institute of Science (IISc) are leading long-term studies on how India-specific factors—diet, undernutrition, multilingualism, and intergenerational living—affect the brain.

Ramani Sundaram, Executive Director of Dementia India Alliance, said that integrating dementia into existing health programmes—such as the National Programme for the Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE), National Mental Health Programme, and palliative care initiatives—could offer scalable, practical solutions.

Love, loss, and care

It all changed for Mary Vinayak, 75, during Covid-19 when her mother died of leukaemia. The shock of losing a parent was unbearably raw. She couldn’t speak. What remained was a broken prayer, “Jesus, please help me.” Her family was stuck in this loop for two long years.

On a friend’s advice, her 80-year-old husband, Clement Vinayak, joined the weary lines outside NIMHANS in 2023—fighting to turn back time. He finally secured a room for Mary after a month of repeated visits. The total cost, covering medicines, food, room, and medical services, amounts to approximately Rs 30,000.

Nothing improved after eight rounds of Electroconvulsive Therapy. But the ninth one worked like a miracle.

The loop was broken, and Mary Vinayak returned from the fog. But not entirely.

“She still can’t sign documents, forgets things that just happened, and flares up if things aren’t done her way,” said her husband.

Clement often mourns Mary’s lost abilities. Once, she managed every detail of their life effortlessly—handling bills, making decisions, keeping everything in order. Now she can’t turn the pages of a book without forgetting, and even diaper changes leave her frustrated and sometimes aggressive.

“The human bond doesn’t fade. What we lose is only the material—the abilities, the routines—but the connection, the love, that remains untouched,” Clement said, looking at his wife.

The lingering guilt

Many families shoulder guilt as they become full-time caregivers, confined to their homes, hiding the realities of dementia, and feeling embarrassed whenever others catch a glimpse of their struggle.

Kamla, now 81, first showed signs of dementia around 2021.

“Last year in May, we initially took care of her at our home in Kerala and then brought her to Bangalore. She wants to go home, but she doesn’t really know where home is,” said her grandson, Arjun (26). He, alongside his mother, took on the role of caring for her.

Kamla often longs to return to places and meet people who are no longer alive. To help her understand loss, Arjun and his mother keep photographs of deceased relatives around the home. It helps.

“Families often get stuck in anticipatory grief, unsure what to do, watching their loved ones slowly fade—grieving before their death, yet still longing for them to stay,” said Kaur.

After Lopa Mudra Sanyal’s father died at the age of 64, her mother found herself alone in Jhargram village of West Bengal.

“She would hide little things—the rolling pin, cups, saucers—inside her almirah. None of us understood what was really going on,” said Sanyal.

In 2015, she brought her mother to Delhi. A psychiatrist in Nehru Nagar finally used the word: dementia.

With time, her mother forgot even her daughter’s name. Memories of her husband faded, too. She went back to using her maiden surname and started calling Sanyal, ‘Didi’. One day, when the doctor asked her age, she said, ‘36’—she was seventy years old.

She had come to India from Bangladesh after the Partition in the 1970s. Sanyal said that the trauma stayed with her somewhere. Her end came slowly and painfully.

“She became like a child,” she said. Tiny, and her skin felt thin like paper.

After her mother’s death, Sanyal began recognising dementia in others. Now, when she meets someone showing similar signs, she speaks to their family, urging them to write things down.

After watching the film Goldfish (22), she realised she should have been kinder and more patient with her mother. “If I could go back in time with what I know now, I would have cared for her differently,” she said. In hindsight, she accepts her mistakes as part of the learning process. The guilt, however, still lingers.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

This article was very useful to understand Dementia and will help families to get support from the right places.