Delhi/Narharpur/Dharwad: Hidden in the forests of Chhattisgarh’s Narharpur is a small cement structure with black Hindi letters on the wall: Naveen Shav Griha, a house for the dead. More than 1,200 postmortems have been conducted here in the last 20 years. The person cutting open the bodies is Santoshi Durga, a sanitation worker. Her qualification is not an MBBS but her caste.

There’s no running water or electricity in the dingy room. Just a worn-down cement slab and a paltry selection of knives. The town’s residents say the murda ghar is haunted, cursed. By extension, they look at 42-year-old Durga with suspicion. But to them it’s only natural that the distasteful job of dealing with the dead is relegated to a Dalit.

“Townspeople say the mortuary is not auspicious, it is scary. So, they pressurised the hospital to make the mortuary outside the town,” said Durga, who works for the Narharpur Community Health Centre as a badli worker, a substitute or proxy.

Sometimes, badlis sweep roads or clean drains for government safai karamcharis who don’t want to get their hands dirty. And sometimes, badlis like Durga fill in for squeamish doctors. For this, they don’t even get the pay or benefits of a permanent sanitation employee.

The doctor never touches the body, he just keeps making notes. I have complete experience now. I know how to cut open the body and break open the skull. I open the body from the trachea to the navel. I show the doctor where the bones are broken, where injuries have been sustained

-Santoshi Durga, contract sanitation worker

Across India—whether in Narharpur or Gurugram, Dharwad or Delhi—thousands of Dalit sanitation workers are forced to perform autopsies. Called “cutters” by the medical fraternity, they get no formal training, protective gear, recognition, or additional compensation. Despite government regulations requiring an MBBS degree as the basic requirement to conduct autopsies, physicians at large do not want to go near decomposing bodies, much less handle the organs. They may supervise from a distance, but the dissection is left to sanitation workers, who are nearly always Dalit. The role is passed down generationally, turning risky medical labour into an inherited caste-based duty. The system continues to reinforce and strengthen age-old, stubborn notions of pure and impure, and lack of dignity is still ascribed to some jobs in modern India.

“This practice is even worse than manual scavenging,” said Bezwada Wilson, convenor of the Safai Karmachari Andolan.

Not only are sanitation workers engaging in a hazardous, traumatising job without prior consent, they’re also stuck in tenuous contract work, forced to labour all seven days of the week. They depend on tips from relatives of the dead to meet their basic needs.

Durga is no stranger to the murda ghar. She learnt the job of dissections from her father, who drank himself to death to cope with the pressures of the work.

“My father used to conduct autopsies here earlier, but he used to get drunk and do it. I wanted to prove to him that this work can be done without alcohol. I learnt the ropes alongside him,” she said.

Yet though the practice is rampant in government hospitals, the work is either invisible or it brings ignominy. Or both.

“No postmortem in this country happens without a safai karmachari,” said Bhim Basfore, member of Assam’s Safai Karmachari Aayog and the son of a postmortem worker himself. “Nobody wants to do this work, and so it is handed over to the sanitation workers. Sanitation workers do three types of jobs: working on the roads, manual scavenging, and cutting dead bodies. There is a lack of awareness about the third.”

Also Read: The Great Indian Sanitation Scam. General castes bag govt jobs, Valmikis do the work

Caste disguised as contingency

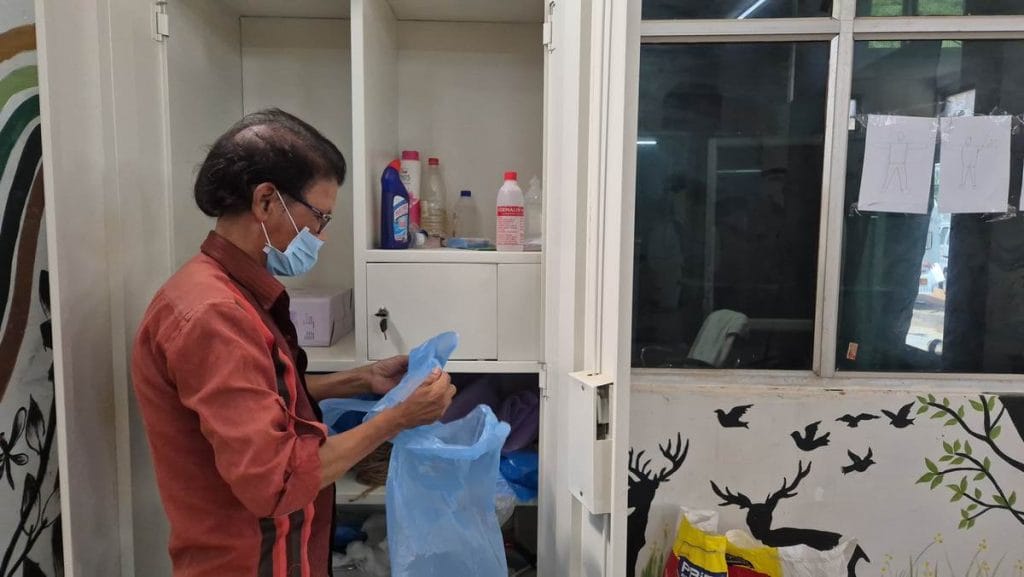

A hammer and a couple of blades kept neatly in a black bag, along with aprons, masks, and gloves are the only tools at Durga’s disposal for her autopsy work. She doesn’t even know what bone saws, rib shears, or specialised autopsy knives are.

Her kit is kept in a far corner of Narharpur Community Health Centre and is labelled with khatra (hazardous) warnings. If further testing is needed, she transports body parts back to the hospital in a basic plastic container.

“Here is the box I keep organs in,” she said, pulling out a blue-lidded Pearlpet box, which she washes and reuses.

Durga is the one doctors and even police call when a decaying body is found, or the victim of a murder or suicide has to be examined. She has to work with whatever she gets. The bodies might be infested with maggots, bloated, or mangled beyond recognition. The sight and stench can be unbearable. She says the state provides her hepatitis shots every quarter. Usually, bodies are brought to the mortuary in a van, with the doctor and Durga travelling together to carry out the work.

“The doctor never touches the body, he just keeps making notes,” she said. “I have complete experience now. I know how to cut open the body and break open the skull. I open the body from the trachea to the navel. I show the doctor where the bones are broken, where injuries have been sustained.”

The people I cut open visit me in my dreams. Earlier I was scared of them. Now I have made my peace with it, but it is still difficult to fall asleep at night

– Sanitation worker in Gurugram

Calling on sanitation workers for mortuary work is just the normal division of labour here. It even happens in Raipur, according to Naharpur block medical officer Bhupendra Kumar.

“The autopsies always happen under the supervision of doctors. We are always present there,” he said.

A senior forensic pathologist from Gujarat argued that there’s a distinction between conducting a postmortem and dissecting a body.

“You need a helping hand for dissection. Dissection procedure cannot be done by a single person,” he said.

The doctor acknowledged that it is a “major lacuna” in the system that Grade D workers end up doing postmortems, but added that India has no “qualified” mortuary attendants.

Some universities have started offering mortuary technician certificate courses—for instance, Manipal University in Karnataka and JIPMER in Puducherry—but they’re rare. As a result, trained workers are virtually nonexistent.

“In India there is no certification for postmortem attendant. Class 4 employees conduct postmortems. We train them to assist us in removing organs, place a dead body on the table, help us in chemical analysis,” said Dr Rajesh Dere, general secretary of Indian Academy of Forensic Medicine, which has 500 forensic doctors registered with it. He, too, noted that this is not an ideal situation: “Ideally even dissection should be done by a doctor only, since it is a scientific procedure, and standardised techniques are used.”

Though doctors often downplay caste when assigning dissection work to Grade D sanitation staff, some practitioners and activists point out that the task overwhelmingly falls to those labelled “untouchable”. These workers face stigma from both within the hospital system and their own communities. It’s caste-based discrimination disguised as a contingency.

Professor Pradeep Ramvath of TISS Guwahati, who has worked extensively with mortuary workers, pointed out that the lack of formal posts or training stems from the work’s entrenched stigma. In the larger caste pyramid, Dalits have always been tasked with disposing of carrion or cremating corpses. So they’re roped in for postmortems too

“What goes to the mortuary? The dead bodies at mortuaries are rotten, charred, butchered. A body that has been decaying for 10 days. Accident victims, suicide cases. No educated person wants to do this kind of work. The smell is [terrible]. Why are you employing these people?” he said, adding that such workers should be immediately rehabilitated.

Forensic doctors ThePrint spoke to also acknowledged that many doctors and medical officers are reluctant to go near dead bodies. Dalit activists say the result is casteist outsourcing.

“It happens at doctors’ behest,” said Basfore, who is also a rising Dalit youth leader in Assam and founder of the Safaikarmi Anusuchit Jati Students Union, which he claims has 10 lakh members across India.

Bezwada Wilson finds this brand of caste-based exploitation especially egregious.

“Everyone is afraid to touch, cut and dissect the dead bodies, so they make the sanitation workers do it. They’re engaged or forced to do this but not considered experts, or compensated for the extra work,” he said.

Blood, bad dreams, bias

Every day is traumatising for the 40-year-old mortuary worker in Gurugram. Sometime, blood splatters into his eyes while cutting open bodies. Sometimes he’s just exhausted from excavating the putrescent insides of cadavers. Some deaths sadden him. There’s no time to process any of it, but the dead linger in his subconscious.

“The people I cut open visit me in my dreams,” he said with a sense of exhaustion in his voice. “Earlier I was scared of them. Now I have made my peace with it, but it is still difficult to fall asleep at night.”

For 22 years, he has assisted with police cases, sometimes autopsying victims of murder and rape. The protective gear is inadequate at best.

There’s no counselling available for people working in these conditions. So many people just lose their minds, become more violent

-Bhim Basfore, Dalit activist

“They only give us masks, but are masks enough? They don’t provide us with proper tools. The chemicals we use for disinfection make my hand burn, and till today the smell of decaying bodies makes me want to vomit,” the mortuary worker added.

If the work wasn’t punishing enough, the world outside offers little relief. His neighbours call him jallad (hangman) and conjure scary stories about him. His children often ask him to change jobs. It is difficult for him to go a day without drinking. It helps him fleetingly forget the sights, smells, and suffering he has to tolerate daily.

Alcohol abuse is common in this line of work. Durga lost her father to it. Bhim says his father’s life was also cut short due to it.

“Sanitation workers in mortuaries are dying silently,” said Ramvath of TISS Guwahati. “In so many cases, by age 35, they start puking blood, develop tuberculosis, or suffer from liver failure,” he said.

At times, drinking is even encouraged at work, according to Basfore.

“Even doctors encourage mortuary workers to have alcohol and then conduct postmortems. Even manual scavengers first drink before entering tanks because that smell is unbearable,” he said.

The combination of occupational trauma, alcohol, and no mental health support means emotional and behavioural issues are common.

“There’s no counselling available for people working in these conditions. So many people just lose their minds, become more violent,” Bhim said. One friend, he added, seemed to become a different person after he was forced into mortuary work: “He was the sweetest boy. But something in him just changed, a violent streak in him emerged.”

Everyone is afraid to touch, cut and dissect the dead bodies, so they make the sanitation workers do it. They’re engaged or forced to do this but not considered experts, or compensated for the extra work

-Bezwada Wilson, convenor of the Safai Karmachari Andolan

Women in the field face even more isolation. Their experiences remain largely undocumented and absent in academic literature.

“They’re often targeted for indulging in ‘witchcraft’. They are being stigmatised even within the community. But there are no studies, no policies to help them. Simply nobody is interested,” Ramvath said, adding so little is known about them that they are like “black boxes”.

Durga says she is exhausted by the invisibility of her work. Her efforts go unrecorded, and the remote mortuary keeps her labour under wraps.

“There is a lot of casteism in this area. I belong to a Dalit family…. People should celebrate the fact that a woman from their village is doing such a brave, important job, they should take pride in it, she added. “But I don’t care about what people say, I only focus on my work.”

Despite being rampant for decades, postmortem work by Dalit sanitation workers has remained in the shadows. Unlike manual scavenging, there have been no petitions or protests.

Basfore wants to change that. Having grown up watching his father do this work, he says it’s his mission to abolish the practice of ‘cutter’ work in mortuaries. For now, he is discouraging sanitation workers from this work via word of mouth, but hasn’t planned any protests so far.

‘Karnataka is 100 years forward’

At the civil hospital in Karnataka’s Dharwad, a young Group D mortuary attendant stood by a body on the autopsy table and rattled off details to the doctor on call.

“The ligature mark on the neck is 27 centimetres, rigor mortis has set in, the body has developed lividity. There are no rope marks at the back of the neck,” he said. Another attendant joined him as the doctor took notes.

The body was that of a 47-year-old man. After finishing his lunch, he had tied a scarf around his neck and hanged himself from the fan. The team’s job was to ascertain whether it was suicide or if there was foul play. The man’s body was swollen and turning blue.

“I have a BSc,” said the attendant, beginning an incision from the trachea. “I was given one month of training and have no problem working this job. I have gained expertise in this work.”

The two attendants conducting the autopsy said they were Lingayats, a religious community in Karnataka that includes various castes.

“Though they say they don’t believe in caste, they still have the Panchapeethas, where five denominations exist,” said Ramvath. “There are Dalit Lingayats.”

The body looked almost like a rubber doll. As the attendant cut deeper, blood was followed by yellow fat spilling out of the body. He examined the man’s lungs, which had developed black spots. “He’s a smoker,” he said. He peered into the stomach and added, “He died shortly after having food.” Then he held up the swollen liver. “His liver is cirrhotic; he could have developed cancer.”

In India there is no certification for postmortem attendant. Class 4 employees conduct postmortems. We train them to assist us in removing organs, place a dead body on the table, help us in chemical analysis

-Dr Rajesh Dere, general secretary of Indian Academy of Forensic Medicine

There were no cloths to contain the mess, so he used the dead man’s clothes to soak up the blood.

The doctor stood next to the table in the room that reeked of chemicals and death, the white tiles yellowing. He made notes based on what the young man was telling him. Toward the end, the worker cracked open the skull with a hammer. A piece fell to the floor. “No signs of haemorrhage,” he said, looking at the brain.

The young man has a permanent job as a Grade D Group 2 attendant. So does his colleague, who is also a ward boy. But they say they still don’t have the right tools, like a brain knife and autopsy saw.

They work seven days a week with no time off, often doubling shifts after accidents or emergencies.

“Our job is 24×7. There is no break,” said the young man smiled.

Even if there are still gaps and caste lines, Ramvath called Karnataka “a hundred years ahead” when it comes to sanitation worker rights. Last year, for example, the state government announced that 24,005 pourakarmikas (sanitation workers) in Bengaluru would be made permanent, and court orders have mandated payments of arrears with interest.

In most states, the majority of sanitation workers are stuck in contract jobs. Government posts fell from 1.26 lakh in 2004 to 44,000 in 2021, as reported earlier by ThePrint.

The ‘perks’ and the precarity

Even if the system is rigged against mortuary workers, there are some perks. These are informal benefits, some of which fall in a moral grey area.

“Kin of the deceased often give money to the sanitation workers or doctors to conduct postmortems, so for one job they can receive between Rs 2,000-5,000,” Basfore said. “Sometimes sanitation workers also retrieve jewellery or cash from the dead.”

What stings more than the smell or the long hours is the absence of job security.

In New Delhi’s Barafkhana, a 29-year-old worker in a green lab gown was between postmortems, having just determined the cause of death of a young woman. He seemed to accept the job as his lot.

“My father used to do this work. After he died, the job came to me,” he said. “We work seven days a week but we work here on contract.”

He recounted how he and other morgue workers risked their lives during the pandemic, handling bodies every day, ever got the respect of ‘Covid warriors’. For now, he’d settle for a permanent job, and with it, a little more dignity.

But permanent jobs are few and far between.

In Chhattisgarh’s Kanker, Rakesh Rajak has been working in the postmortem room at Komal Dev District Hospital since 2010, without a single weekly off. He earns just Rs 10,000 a month.

Now 47, Rajak is above the age at which his job can be regularised. The maximum age is 45 in Chhattisgarh.

“Even if I’m over the age limit, what does it matter? I’ve been doing this work for 15 years,” he said, exasperated.

Some 50 kilometres away, Durga’s home is completely empty. There are no fans, no furniture bar a stool. Just a few pans and plates in an otherwise bare kitchen. It’s a five-minute walk from the hospital, where her contract entitles her to just Rs 8,000 a month.

She wants a better life for her two daughters. Her husband is a daily wage labourer.

“My children will never do what I do, I want to educate them. All I want is a permanent job to be able to do so,” she said.

She doesn’t have the luxury to question the systemic discrimination that pushed her into this work. But better amenities to do her work would help. The mortuary got a freezer recently, but it’s still locked up at the Community Health Centre.

Also Read: Dalit women reclaiming Punjab’s farmlands. ‘We are born on this land, have a right to it’

Question of qualification

Through years of practice, sanitation workers learn to conduct postmortems with skill. But experience alone cannot rival a degree in medicine.

Indian courts have time and again flagged how botched autopsies threaten the very foundation of the criminal justice system. They blame doctors for oversight.

In 2020, the Madras High Court warned that autopsies, which are key to medico-legal cases, were being conducted in a “shabby and unscientific manner,” risking a “complete collapse of the criminal justice delivery system.”

“Doctors are not going near the bodies and dictating the injuries to their assistants and noting of the injuries and findings are also not as per the format,” the court had observed.

A senior police officer in Ahmedabad said most autopsies, in his experience, were “unreliable.”

“In complicated cases, sometimes labs or doctors write ‘suspicious’ malignancy on the report which really doesn’t mean anything. When the body has decayed, if it is 4-5 days old, then it becomes really difficult to ascertain the cause of death,” he said.

Even MBBS doctors are not necessarily up to the task due to the lack of specialist training, according to Dr Dere of the Indian Academy of Forensic Medicine.

“There is a huge dearth of specialised forensic doctors in India. About 90-95 per cent of all postmortems in India are conducted by MBBS doctors. They’re not specialised in this, though they are eligible to conduct [autopsies],” he said.

It’s like comparing an MS surgeon examining an acute abdomen to an MBBS doctor doing the same, he pointed out—”there’s a hell of a difference.”

He added there are multiple cases in which the high courts have rapped medical officers for not conducting proper medical autopsies.

In 2024, for instance, the Punjab and Haryana High Court, while hearing a revision petition, expressed shock at the quality of autopsies. Justice NS Shekhawat had noted that the postmortem failed to identify a cause of death, and that unscientific dissection led to the confusion. The postmortem was done in a “casual manner”, the court contended.

“This court is conscious of the importance of medical evidence in the disposal of criminal trials,” the ruling said. “However, sadly nowadays, it has been noticed and it is a matter of common knowledge that the dissection is being done by persons other than the doctors/ forensic experts… Due to this the postmortem reports do not accurately reflect the findings as found on the body.”

The court also directed the state and UT health departments to submit memorandums on how postmortem procedures are conducted.

Botched autopsies can also result in missing organs, and criminal intent can’t always be ruled out. Last year, two doctors in Uttar Pradesh were suspended after it was alleged that her eyes were removed during her autopsy. It was later determined that the damage may have occurred during the procedure and the eyes had not been removed for “illegal sale”.

What might make autopsies more reliable is formal training for those who’ve already learned on the job. According to Wilson, the jobs must be immediately regularised and the post of a postmortem worker created.

“Promote these people who are already experts. Give them proper gear so that they don’t contract diseases,” he said. While AIIMS Delhi has separate openings for post mortem attendants as Group C workers, this is not generally the norm. ThePrint tried to contact the AIIMS forensics department through the hospital’s media line but received no response.

But in Chhattisgarh, Durga is still reckoning with one of the crueller ironies of contract work. She’s considered skilled enough to do the job of a doctor at the murda ghar, but not qualified enough to be made permanent.

“I have asked for a permanent job at the hospital a number of times, but they tell me I need a distinction in class 10th and 12th to qualify. Now, I am 42 and time is running out,” she said.

This article is part of a ThePrint series documenting new forms of occupation-based caste exploitation. Read the other articles here.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

What a marvellous, brilliantly written news story. A classic case study of what a good press reporter can do: educate, inform, show a mirror to society and the authorities and above all, trigger reflection about why things are as they are? No value judgements, no sermons. Just the facts as they are. Kudos and huge respect to Shubangi Misra.