Ballari/Koppal/Bagalkot: When Huligemma went to school for the first time, the teacher asked her father’s name. She did not have any idea. Whispers followed her down the corridor — “sule maklu”, prostitute’s child.

“I never looked for a father. Although I always knew a father figure in life would have security, which my mother did. I heard people saying my mother is a devadasi. It took me time to understand,” said the 21-year-old, who lives with her mother Kenchamma and three siblings in Sandur village, Ballari district.

Now a new state law in Karnataka is going beyond a 1982 ban on the devadasi system. It promises housing, healthcare, inheritance rights, and protection from stigma for both devadasis and their children. The practice, which consecrates mostly Dalit women to temples but brands them as prostitutes, continues to haunt tens of thousands of lives across the state.

But who benefits also depends on who gets counted.

The State Human Rights Commission has asked the Siddaramaiah-led Congress government to finish a survey of Devadasis and submit recommendations by 23 October. The last survey in 2007-08 counted 46,660 women across Karnataka. The reach of the new law’s benefits will depend on how this survey is done. If, as before, it includes only women dedicated before the 1982 ban, younger Devadasis like Kenchamma — and by extension her daughter — will be left out again.

Earlier this month, Siddaramaiah announced that the Devadasi survey will be carried out starting from the first week of September.

“If the Devadasi system is still alive today, it is a matter of shame for all of us,” he said.

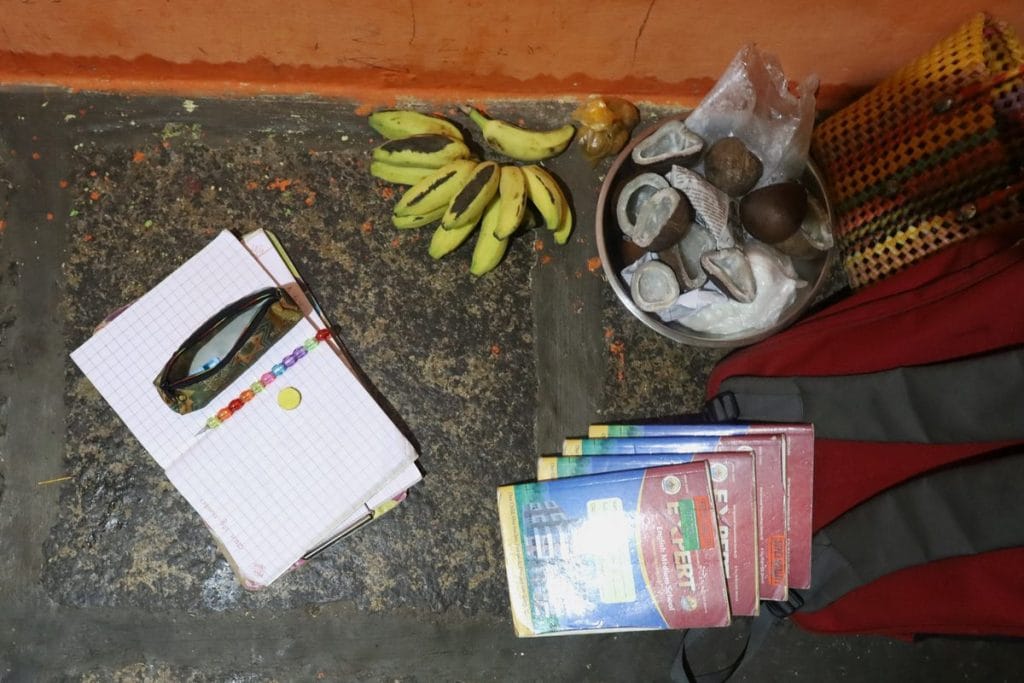

Devadasis are poised at the thorny intersection of caste, religion, and sex work. Huligemma first heard about the Karnataka Devadasi (Prevention, Prohibition, Relief and Rehabilitation) Act, 2025, passed in the state assembly on 18 August, through a community newsletter. She narrated it to her mother, who struggles to read.

“My mother is hopeful we four children will now be able to live a life free of poverty and discrimination,” said Huligemma. In their single-room home, she prepares sugary milk tea for Kenchamma.

“I know the horrors. I will never let my daughter go through this,” said Kenchamma, a frail 45-year-old who was only ten when her parents dedicated her as a devadasi because she was “beautiful” and they needed the money. She pulls out two necklaces hidden under her blouse: a white-red beaded muthu and a mangalsutra tied at the temple. They were meant to mark her as a handmaiden of the goddess; in practice, they marked her out to men as a sex worker.

When I was applying for a passport, it was so difficult to get away with the column for my father’s name. It was the worst experience. With this law, devadasi children will no longer be subjected to such atrocity

-Nari Kamakshi, daughter of a devadasi

“It is the worst practice, people only see you as a sex worker,” said Kenchamma, who now works as a farm labourer.

More than her three sons, she dotes on Huligemma, who is doing her BA (general course) at a local college. But it’s a struggle. She has not been able to pay fees for this term.

“I do not want to leave studying, it is the only way my family and I can move out of this hell,” Huligemma said.

Centuries ago, no one knows exactly when, girls from poor families were dedicated to goddesses to serve in temples. What began as ritual worship turned into systematic sexual exploitation of Dalit women, particularly from Madiga, Madar, and Holeya communities. In Karnataka, about 95 percent of devadasis are Dalit. In 1982, the state banned the practice through the Devadasis (Prohibition of Dedication) Act. Yet the system stayed entrenched across northern districts like Belagavi, Vijayapura, Bagalkot, Koppal, Ballari, Raichur and Kalaburagi.

To wrest themselves free, women have relied on educating children and asserting dignity through caste pride. The state’s role has been minimal, though those counted in the last survey received devadasi certificates through which they accessed some benefits. Some received land, pensions of around Rs 2,500, and financial incentives for marriage—Rs 3 lakh for men marrying a devadasi, Rs 5 lakh for women.

This time, devadasis had a bigger say in shaping the law. It was drafted after seven months of research by a National Law School of India University (NLSIU) team working with NGOs, activists, and more than 15,000 devadasis. Children of 15 devadasis documented problems and suggestions across districts in northern Karnataka. Consultations followed, with the community itself proposing changes to improve their lives.

RV Chandrashekar, coordinator of the drafting committee, said the survey would spell out caste details and show how the practice is bound up with casteist oppression.

“Among Dalit women, devadasis are lowest on the social ladder, and the caste census in the survey will prove that,” he said. “It will give them and their children a better life.”

Also Read: Why calls for fresh survey of devadasis have ignited both hope & despair in Karnataka

Dual stigma

In the Harijan colony of Bagalkot’s Rabkavi town, 33-year-old Lakshmi drapes a red-and-white chiffon saree, puts on lipstick and kajal, and sends her two children to the back room. It is sundown, the time when she starts getting customers at her doorstep, though she’s worried the incessant rain might keep them away.

Lakshmi is a second-generation devadasi. She was 12 when her mother encouraged her into the profession. Unlike her four sisters, who were good at studies, her only skill was singing and dancing. For her desperately poor Dalit household, dedicating her was a way out.

“Ma told me not to make noise, cooperate with the man, just do the deed,” said Lakshmi. “I did not cry, I was numb. It was just for 20 minutes.” She laughed as she spoke, as if the memory belonged to someone else.

Fifteen years later, Lakshmi sits in the same room. Nothing has changed apart from her two children, both born of accidental pregnancies.

“Those men did not wear condoms,” she said.

Her neighbour Lucky, 38, wearing a floral black saree, is also waiting for customers. She gets continuous video and voicecalls.

“He is my lover, he calls me 15-20 times a day,” she giggled, showing off the dark green bangles he bought her and his name “Sindhu” tattooed on her arm. “He has a wife and kids, but he loves me. He takes care of me and my children.”

At the age of ten, Lucky was hired as a domestic worker at a Devadasi house, where she learnt about the system. What rang the bell for her was money.

“I used to give water to guests, clean the floor, and while doing this I came to know about the dedication,” she said.

She willingly went to the temple and tied the thread, convinced it would bring her money and comfort. She had no idea what it really entailed.

“I think a year later, when people came to know I was a Devadasi, a man knocked on my door. I did not understand how this system was a curse till the time the man forcibly penetrated,” Lucky said. She has not heard of the new law and sees no way out. When a customer appears, she disappears inside with him.

I did not know who Ambedkar is, but while protesting for my rights I realised his value. He is our god

-Vijaylakshmi, devadasi from Koppel

Despite the Devadasi system being ‘abolished’ on paper, it flourishes in Northern Karnataka. This region has one of the highest Dalit populations in the state, with many households living in abject poverty. For such families, activists working in the region say, dedication seemed like a way to secure blessings and support. Threads were once tied openly in the temples of Yellamma (Renuka), Huligemma, Durgamma, and Kenchamma. Instead, it only added another layer of systemic oppression. If Dalits were at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, the devadasi system placed women at the very base of that pyramid.

Religion lends only a tenuous veneer of ‘respectability’. Throughout the northern districts, women remain strong votaries of the goddess Huligemma and prepare rigorously for worship days on Tuesdays and Fridays, when they gather at the Huligemma Devi Temple in Hospet. Mondays and Thursdays are spent cleaning their homes, making sure everything is “pak” (pure). On temple days, they dress in green, the goddess’s colour, and add lipstick, flowers, and green or silver bangles with goddess motifs.

But caste rears its ugly head even then. In Hospet, they carry red and yellow colours in bamboo bowls, called bhiksha patra, through the village, asking for donations. It is framed as ritual, not begging, but rests on caste-based discrimination.

The temple throngs with devadasis on these days, but for the rest of the week they are not allowed to worship or touch the goddess, even at home. They comply with these rules, fearing divine anger.

Among Dalit women, devadasis are lowest on the social ladder, and the caste census in the survey will prove that. It will give them and their children a better life

-RV Chandrashekar, coordinator of the NLSIU law drafting committee

Lakshmi keeps her gods in a corner of her house, in a room where men are not allowed. She will not touch them if she has been touched by a customer.

“We do not want more problems in our lives, we are living with a curse already,” she said.

Even Devadasis who leave the system are not fully able to gain acceptance in society.

Land, dignity, Ambedkar

Over 100 km from Bagalkot, Vijaylakshmi returns home soaked in rain from a cotton field in Bannigola, Koppal. She was allotted this land four years ago, after a long struggle by activists associated with Vimuktha Devadasi Mahila Mathu Makkala Vedike, a community-based organisation of affected devadasi families. The efforts of Prof YJ Rajendra, activist Chandalinga Kalabandi, and others, through interaction with devadasi women to learn about their issues, proved instrumental in the formation of a social movement.

For the former Devadasi, this work was supposed to be freedom. But some upper caste villagers still refuse to speak to her.

“Sometimes they refuse to buy our cotton because it is grown by untouchables,” she said.

Her entry into the devadasi system was bound up with family obligation. Vijaylakshmi’s parents dedicated her so she would not marry and could stay home to care for her disabled brother. She nursed him until his death at 18, when she was 28. Now 42, she says her parents “sacrificed” her.

“I curse my parents every day,” she said, covering her face as tears spilled down. “They left me to live like this.”

Her life began to change when land rights were won for devadasis in Koppal. That movement started more than two decades ago, led by Vimuktha Medike. Chandalinga Kalabandi, the grandson of a devadasi and a member of Vimuktha, along with others organised protests and pressured local authorities to speed up allotments of public land.

What once took years could be done in months and he is now revered by local devadasis. Unlike elsewhere in northern Karnataka, Koppal saw a genuine grassroots revolution.

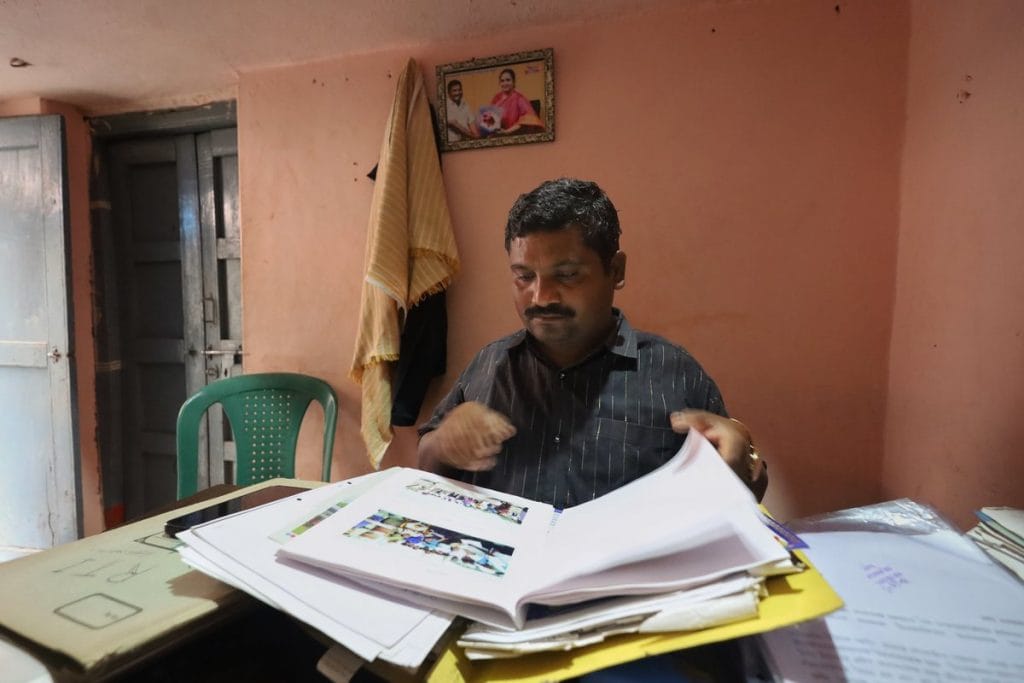

“What we have done for devadasi women in this district, this law will bring the same changes across Karnataka,” said Kalabandi in a tiny room of the Vimuktha Devadasi Mahila Mathu Makkala Vedike.

Vijaylakshmi is one of 150 women now farming on their own plots in Koppal. Her sons, Parshuram and Suraj, help her tend the cotton. The money is meagre, and she says she cannot save much, but there is more dignity.

“I have my own land now, at least something to call mine. I am no more a devadasi, at least financially,” she said.

Another change in her life is caste pride. In the front room of her house, which she shares with her mother and sons, hangs a portrait of BR Ambedkar, with a red tilak and tripundra on the forehead. Every day the family lights agarbatti to their gods, departed relatives, and to Ambedkar.

“I did not know who Ambedkar is, but while protesting for my rights I realised his value. He is our god. He gave us the Constitution,” she said.

In villages where the devadasi tradition runs deep, Ambedkar’s image is on many walls. For these women, it offsets a cruel tradition with the hope of change. In many of their homes, Ambedkar’s words echo: “Educate, Agitate, Organise.”

The upcoming devadasi survey will, for the first time, include a caste column, offering a clearer picture of Dalit women’s oppression. NLSIU’s Chandrashekar said this “orientation” goes beyond the national caste census, as it captures how the devadasi system specifically intersects with caste.

For devadasis, the state survey is critical. In the last one, women were given a survey number that helped the government identify them for benefits but an age limit left many younger women. That rule has not been scrapped.

Shamla Iqbal, secretary of Women and Child Development in Karnataka, confirmed that only women dedicated before the 1982 ban will be officially recognised.

“Forty-five years age is still intact,” she said, adding that if women were made devadasis after the law, “proper investigation will be done at the taluka level and then they will be given certificates.”

However, Chandrashekar said the drafting committee is preparing fresh requests to remove the cap altogether, so younger women and their children are not excluded from entitlements.

Overall, the process of getting devadasi and caste certificates is expected to be simplified.

“My mother had to go through pillar to post to get the devadasi caste certificate in around 2016-2017. We hope this law makes the procedure a little easier for the women,” said 27-year-old Nari Kamakshi, who was involved in doing the survey of devadasis for the law draft.

Also read: Dancing women of UP and Bihar

Law that fights stigma, holds fathers accountable

When Vijaylakshmi talks about the father of her children, her lips curl slightly. She says she once loved him dearly but no longer. Her voice softens as a man in a white lungi and crisp shirt enters the room. It is 65-year-old Allappa Valmiki, the former village president who calls himself an advocate of devadasis’ rights.

“The system was started by our ancestors and we just followed them. Now, we know it has oppressed a lot of women,” he said, adding that he does what he can for their social acceptance.

Vijaylakshmi goes into another room. She murmurs that Valmiki’s brother, who already has a family, is the father of her two sons. It is an open secret. Nobody says it explicitly, but taunts fall on her all the same.

In these villages, men are spoken of as providers. But for devadasi families, it is the women who raise children and keep households afloat. Fathers are rarely acknowledged while mothers and even children are ostracised.

This stigma is one of the things that Karnataka’s new Devadasi law attempts to address. It allows the child of a devadasi to name their father, with provision for DNA tests if required, and to demand maintenance if paternity is proven. It also mandates administrative reforms so that no child of a devadasi is discriminated against for lacking a father’s name in government documents — from passports and PAN cards to ration cards and school forms.

“When I was applying for a passport, it was so difficult to get away with the column for my father’s name. It was the worst experience. With this law, devadasi children will no longer be subjected to such atrocity,” said Nari Kamakshi. “Nobody will think my documents are fake just because I don’t have a father’s name.”

The law requires taluk-level committees to identify devadasis and issue identity cards within six months of the Act taking effect, making families eligible for land, housing, and healthcare schemes. It also provides for shelter houses—many devadasis have no place to stay, with some living in temples and others on the streets.

It raises penalties for dedication rituals too, with jail terms of two to seven years (the upper limit earlier was five years) and fines starting at Rs 1 lakh, compared to Rs 2,000 previously.

“It is the first time that such a comprehensive law has been introduced in Karnataka. No other state has taken such a holistic approach,” said RV Chandrashekar.

Tamil Nadu (then the Madras Presidency) passed its Devadasis (Prevention of Dedication) Act in 1947, allowing Devadasis to marry and barring new dedications, but offered no support beyond that. Andhra Pradesh followed with a law in 1988, and Maharashtra (then Bombay Presidency) had a Devadasi Protection Act as early as 1934, which was replaced in 2005. All largely stopped at prohibition, without creating explicit mechanisms for reintegration.

Activist Chandralinga Kalabandi now plans to seek national-level data on devadasis through the Right to Information Act, pointing out that while other states have laws, the future of women and their children is uncertain.

What is giving many families hope in Karnataka is that the new law also pledges “priority admission” for devadasis’ children in government schools and colleges, along with special scholarships. It also provides for sensitising teachers so students are not harassed over missing paternal details.

Most devadasis cannot read or write, but they want their children to have education and a clean slate. Kenchamma’s daughter Huligemma is the first in her family to attend college. Vitthal, son of a former devadasi, has completed his master’s in Bangalore and is applying for a PhD.

Vijaylakshmi said she no longer has contact with her children’s father and has made peace with the past. What matters now is whether her sons can build lives free of the label she cannot escape.

Also Read: Dalit women reclaiming Punjab’s farmlands. ‘We are born on this land, have a right to it’

‘Why should I hide?’

Many devadasis place almost as much faith in Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah as they do in the goddess Huligemma.

In Kyadiguppa village of Koppal, 65-year-old Peddamma boldly holds up her palm to represent the Congress hand symbol.

“Congress is our only hope. They saved us earlier and they will again,” she said.

Many devadasis view Congress as a party for the poor. Kamakshi’s mother, Huligemma, recalled “Indira Ma” as a leader who once visited their village and met poor families. “Congress values humans and farmers,” she said.

Regardless of who was in power, though, devadasis have continued to suffer here.

Peddamma cannot remember the exact moment she was dedicated, only the pain and anger. She lost her parents young, and her grandmother thought dedication was the only way to protect her. Soon after, villagers began to treat her differently.

“They called me a prostitute,” she said, sitting in the patch of lawn outside her small home. Her old rage still flares, such as when she spoke of a tailor who raped her repeatedly in her youth.

“I will kill him,” she burst out, hands clenched, nostrils flared. She fell in love with another man a few years later, who took care of her and her children until his death, but they never married. The big bindi on her forehead is just sringar (decoration).

Like Vijaylakshmi, Peddamma was allotted land and grows cotton. But she is still considered an outsider. Her most trustworthy companion is a furry white neighbourhood dog who follows her everywhere.

“If not for this camaraderie it would not have been possible to stay alive,” she said.

Back in Kenchamma’s house in Sandur, women in orange, blue, and red saris crowd into the single room. They are headed to the temple together on a Tuesday morning. Ankamma and Anmakka, Kenchamma’s childhood friends and neighbours, are among them.

Being treated as outcasts has brought the Devadasis together. They talk about the men who pay to sleep with them, their daily struggles, the TV soaps they follow. When they go door to door to ask for bhiksa (alms), some families give rations. But the rounds also become gossip sessions, spaces to vent about the indignity of having to ask. Their expressions, however, are defiant, not imploring.

Even as the new law aims to address social stigma, many of these women have for long refused to internalise shame. They are not living in the shadows or masking their identity.

“I have not done anything wrong, why should I hide?” said Kenchamma.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)