Vadnagar: A few kilometres from the fortified city of Vadnagar, batches of ancient pottery shards dry in the sun after being washed. A team of experts from Deccan College and archaeologists hunch over their laptops, studying photos of artefacts unearthed from ‘Site 33’ of the Vadnagar Project.

The question looming over them—where did the first settlers of Vadnagar come from?

Famous for being Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s birthplace, this town in Gujarat’s Mehsana district now stands poised for national recognition because of the historical enigmas it could resolve.

The story traces back to 1952, when eminent archaeologist SR Rao, who was instrumental in the discovery of the Harappan city of Lothal, reported finding red polished pottery in Vadnagar. This ignited a quest to find the origins of these ceramics, but as the layers of earth were chipped away over the years, a far more expansive story unfolded.

There is now scientific data to prove the existence of an ancient town where people lived continuously for nearly 3,000 years, through the rise and fall of empires and the ebb and flow of invaders. Not just this, the findings suggest a continuous cultural evolution in the broader region for over 5,500 years, potentially disproving theories of a ‘Dark Age’ or period of stagnancy in the aftermath of the Harappa Civilisation.

“The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has been excavating since 2014. But still, there is a lot to discover. If you see the fortification, only a small portion of it is visible. If you want to make a site of World Heritage status, there is a lot of potential in it,” said Abhijit Ambekar, superintendent archeologist with the Vadodara ASI. He has been leading the project since 2016 and co-authored a paper published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Quaternary Science Reviews last month that consolidated scattered findings about the site and put Vadnagar in the media spotlight again.

Ambekar noted that the site holds potential not just for further archaeological studies, but as a major tourist attraction.

“Where else can you get to see such fortifications in India?” he pointed out. Whatever fortifications you see are from the Mughal era. Here you will find structures from the 2nd century BCE.”

Taken together, the disparate findings about Vadnagar reveal a unifying thread through the ages—the remarkable resilience of its inhabitants.

Also Read: Surat’s Swachh sweep—how diamond city went from plague to podium in 30 years

‘A holistic picture of India’

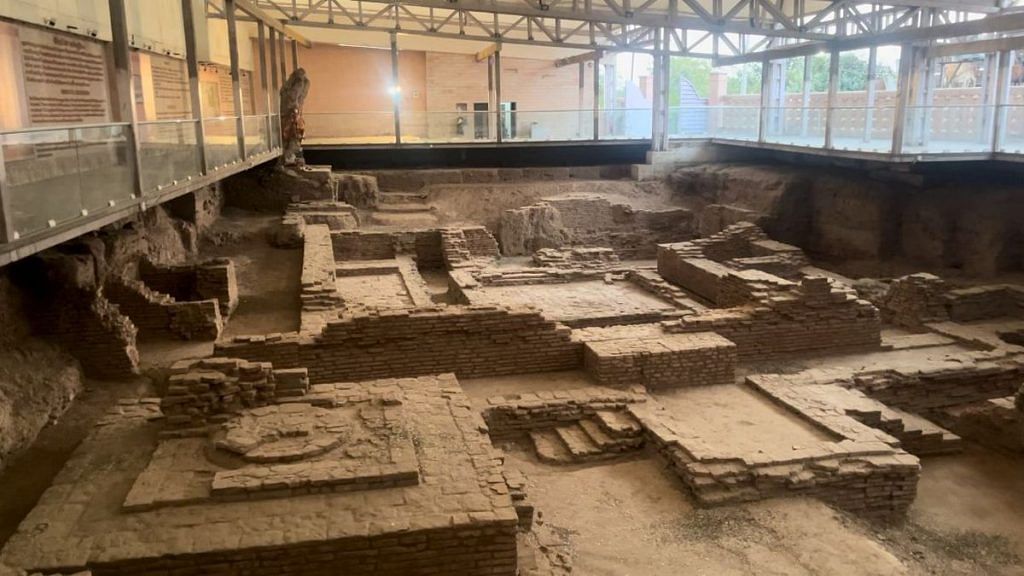

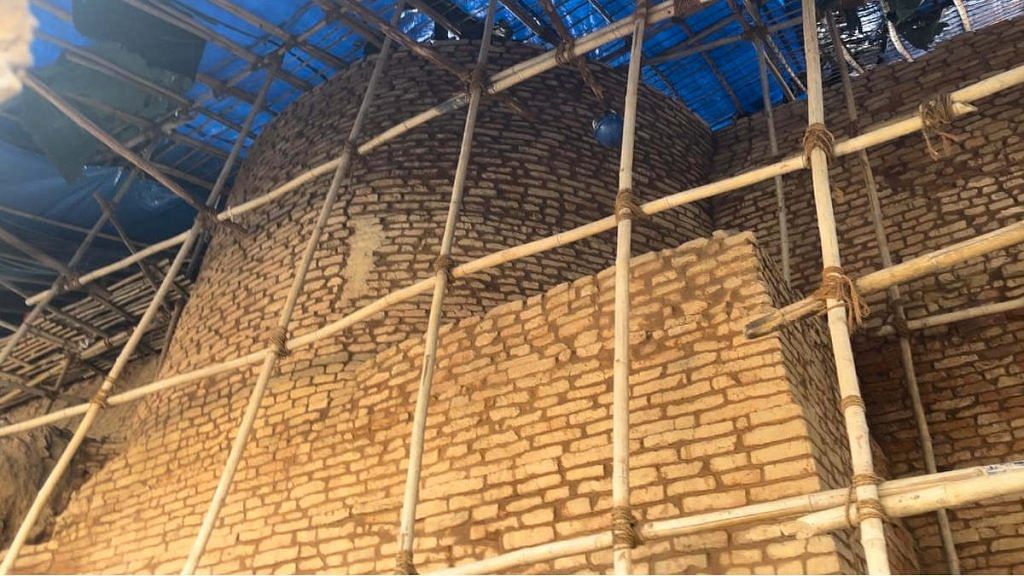

A nearly 4,000 sq ft expanse of blue tarp held up by bamboo scaffolding stretches out near the entrance to the fortified city of Vadnagar. This is Amba Ghat, a dig site, and there is far more to it than meets the eye. Underneath the covering, meant to block out the sun, only a maze of brick walls and shadowy trenches can be discerned, but many of these ancient structures reach as far down as 20 metres deep.

When India’s first archaeological experiential museum opens beside these ruins, the site will swap its temporary cover for a permanent pavilion, allowing visitors to brush shoulders with millennia of history.

Prime Minister Modi’s ancestral home is about a 10-minute drive from the under-construction museum. Both stand within the historic ramparts of Vadnagar, perched on a mound rising 20 to 24 metres high. After nearly a decade of rigorous excavation and analysis, a team of scientists and historians have concluded that this mound harbours India’s oldest continuously inhabited city within a single fortification.

Modern-day Vadnagar is built upon layers of history that stretch back to 800 BCE, encompassing remnants of the Iron Age, late Vedic, and Pre-Buddhist Mahajanapada periods, and beyond.

Since 2014, the year Modi became PM, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) took over excavations from the state archaeological department to establish the chronology of different settlement phases and help create the experiential museum. It was during the later phase of their work, from 2019 to 2022, that they made bigger strides.

After scrutinising 30 sites across the town, the ASI, along with six other research institutions, including IIT-Kharagpur and Jawaharlal Nehru University, undertook the task of putting together different ends of the scattered discoveries.

Some of our recent radiocarbon dates are suggesting that the settlement could be as old as 1400 BCE, contemporary to the very late phase of the post-urban Harappan period. If true, then… the so-called Dark Age, may be a myth

-Anindya Sarkar, lead author of the 2024 paper

Last month, the publication of their research paper, titled ‘Climate, human settlement, and migration in South Asia from early historic to medieval period: Evidence from new archaeological excavation at Vadnagar, Western India’ in Quaternary Science Reviews, sparked a reassessment of the widely accepted notion of a “dark age” following the Indus Valley Civilisation’s demise and the emergence of the Mahajanapadas, or 16 kingdoms of ancient India.

“These kinds of studies were lacking earlier. We have already taken up DNA studies from 2017 onward. But now, we want to see what kind of population lived here,” Ambekar said, adding that further genetic studies are planned along with an investigation of earthquakes in the region by the Institute of Seismological Research.

Collaboration between different institutions has been key in the Vadnagar excavations, enabling the team to accurately date various historical periods.

“This kind of data that is coming out from this site could help other excavation projects,” Ambekar said. “It can show the studies that can be taken up so that a holistic picture of India can come up.”

The recent collaboration between seven research institutions broke new ground by studying Vadnagar’s climate and its impact on successive settlements.

The seven eras

The archaeological buzz surrounding Vadnagar hasn’t touched the modest residential neighbourhood within the fortified area. Houses stand shoulder-to-shoulder, and narrow lanes, barely wide enough for a single car, weave through the locality. In the afternoon, the area looks almost deserted, but the past is always a palpable presence.

An imposing 12th-century gateway, the Arjunbari Darwaja, marks the entrance—a legacy of the Solanki king Kumarpal. The Solanki period is among the seven distinct cultural eras that Vadnagar has witnessed until the 19th century.

As Vadnagar continues to reveal its historical significance, the establishment of a dedicated archaeological museum will play a crucial role in preserving and showcasing its rich heritage.

From what is known so far, the first to settle here were the Indo-Greeks, who held sway until 100 CE, according to the researchers. They were followed by the Indo-Scythians or Shakas (also known as the Kshatrapa kings) who ruled until 400 CE. Next came the Maitrakas of the Gupta kingdom, and then the Rashtrakuta-Pratihara-Chawada kings who reigned until 930 CE. The Solanki kings, representing Chalukya rule, held power until 1300 CE, giving way to the Sultanate-Mughals who ruled until 1680 CE. Finally, the Gaekwad-British era marked the last historical period.

We have already taken up DNA studies from 2017 onward. But now, we want to see what kind of population lived here

-Abhijit Ambekar, ASI archaeologist

However, some chapters of Vadnagar’s history have received more attention than others. At one point around the 7th century, Vadnagar became an important centre of Buddhist learning, and was even documented by Chinese explorer and monk Hiuen Tsang in his 641 CE travelogue Travels in India. Excavations by the state Archaeology Department between 2005 and 2012 unearthed remains of an ancient monastery, now under a well-maintained enclosure under the Gujarat Tourism Department’s care.

But in stark contrast to the Amba Ghat ruins, which will be complemented by a dedicated museum, these Buddhist ruins are located in a neighbourhood permeated by the odour of cow dung and hardly see any visitors.

Researchers are investigating whether Patan, the Chavada dynasty’s capital from 690-942 AD and later the Solanki seat of power, could serve as the missing link between Vadnagar and the earlier Harappa settlements (3300-1300 BCE)

Studying climate, discovering resilience

Even before this year’s research paper, Vadnagar was recognised as an archaeological gem, with the discovery of pottery from various cultural eras suggesting flourishing local and international trade.

However, the recent collaboration between seven research institutions broke new ground by studying Vadnagar’s climate and its impact on successive settlements. Apart from ASI, JNU, and IIT-Kharagpur, the endeavour involved researchers from Ahmedabad’s Physical Research Laboratory, Pune’s Deccan College, Taipei’s Institute of Earth Sciences (Academia Sinica), and Kolkata’s Indian Institute of Science Education and Research.

“We studied molluscan shells found during excavation. Their growth depends on temperature and humidity. So, it gives us a snapshot of the monsoon in India. Based on the oxygen isotope study, we have the climatic data up to the millennium,” Ambekar said.

This data proved invaluable in understanding how Vadnagar was impacted by both favourable and unfavourable climate conditions. The researchers concluded that each of the seven cultural periods thrived during periods of robust monsoons. However, from the 13th century CE onwards, severe aridity impacted western India, including Vadnagar. But the communities did not wilt—they adapted by changing their agricultural patterns.

“Earlier, they cultivated rice, but then they completely changed their agricultural practice to a drought-resistant crop—millet,” the archaeologist said.

The paper also attempted to draw links between climatic conditions and invasions. “We suggest that the seven major phases of invasions/migration to India over the past 2200 years occurred during periods when… Central Asia was hyper-arid and uninhabitable, but the agrarian subcontinent was prosperous with relatively stronger Indian summer monsoons,” the paper says.

Taken together, the disparate findings about Vadnagar reveal a unifying thread through the ages, according to Ambekar—the remarkable resilience of its inhabitants. Faced with natural disasters and changing climates, they adapted their agricultural methods, dug wells and connected waterbodies to cope with drought, and even rebuilt their town after earthquakes.

“People usually leave sites after an earthquake, but they rebuilt the town. Solanki king Kumarpal rebuilt the fortification. They kept adapting to the changes around them,” he said.

Also Read: Gujarat’s true crime drama—flying gold coins, fleeing labourers, police chase, & an alert ASI

Throwing light on the dark age

At the ASI base in Vadnagar, two workers wash and rinse a batch of salvaged fragments brought in from another site in Patan, Gujarat. Another pair of workers diligently wash and strain soil to separate charred grains, which will be subjected to scientific analysis.

Sejal Gotad, who joined the ASI fresh out of college two years ago, observed the drying pottery pieces thoughtfully. These artefacts, unearthed from the Sarval site in the Patan district, where previously Harappan sites have been reported, might hold clues to the origins of Vadnagar’s first settlers, she said. Researchers are investigating if this could be the missing link between the Early Historic and late Harappan periods.

“We find both coarse and fine pottery from the Harappan context. Some of the shapes reported previously in the early Harappan context also have been identified at the Sarval excavations,” said Gotad, who has been stationed at Vadnagar since joining the ASI.

The paper underlines a historical blank spot: a “long hiatus” between the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation around 4,000 years “BP” (before present, which in this time scale means 1950) and the Late Iron Age/Early Historic Period, around 2,500 years BP.

Professor Anindya Sarkar, the lead author of the paper, said the Vadnagar settlement can shed some light on what really happened in these ‘dark’ times.

“Some of our recent radiocarbon dates are suggesting that the settlement could be as old as 1400 BCE, contemporary to the very late phase of the post-urban Harappan period. If true, then it suggests a cultural continuity in India for the last 5,500 years… the so-called Dark Age, may be a myth,” Sarkar said in a press statement before the paper was published.

At the excavation site in Amba Ghat, work is in full swing to not just build the museum but also beautify the area adjacent to a nearby waterbody, the Sharmistha lake.

Ambekar has stationed a draftsman, Mukesh Thakur, to tackle the influx of mediapersons at the site. Thakur, a Vadnagar resident, has been assisting the ASI since 2007. Equipped with laminated charts depicting the settlement design, fortification walls, and waterbodies, Thakur delivers a succinct recap, covering everything from the first excavations by SR Rao in the 1950s to the ongoing collaboration between seven institutions. Since the paper was published, he has given interviews to over 30 media outlets.

“What we are seeing here is an inverted book. The last page is what we can see,” he said. “We are trying to turn the leaves over and search for the starting page.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)