Chandigarh: Two years ago, Aruna Chauhan and her family packed up their belongings, closed the doors of the house they had lived in for over three decades, and left Chandigarh. The decision was not easy, but it wasn’t sudden either. Chandigarh was, after all, a different kind of Indian city, offering quality of life, wide roads, sidewalks, and planned, well laid out neighbourhoods. But all that is now changing.

The Chauhans are tired of the street vendors, the waste, and the growing number of cars. They wanted a better life for their kids and for themselves, as they grow older. They are not the only ones who have either left or sold their apartment in Sector 41. Around 50 per cent of the apartments in the once-coveted locality are now either up for sale or being rented out.

“Chandigarh was different once. It gave us a better quality of life. Now it feels like any other Indian city, chaotic,” said 53-year-old Chauhan.

As Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru struggle with congestion, chaos, and commuter woes, there was always something of a Chandigarh exceptionalism to India’s urban story. Its walkable streets were the stuff of envy in the rest of India. Now it appears Chandigarh has become a victim of its own early immaculate success. The edge that Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier gave to the city is blurring.

The first planned Indian city, an ambitious Jawaharlal Nehru urban project, Chandigarh offers wide footpaths with trees on both sides, often broader than the primary roads of many Indian cities. But after 75 years, these hallmarks are being overtaken. Overpopulation, migration, traffic congestion, and a failing waste management system are forcing “Chandigarians” to rethink the city as their retirement haven. Chandigarh is now becoming just another Indian city.

“Chandigarh is at a critical stage. It is almost at a precipice,” said Deepika Gandhi, who was director of the Le Corbusier Centre from 2015-2022, and a former associate professor at the Chandigarh College of Architecture. “One misstep and we could go down a rabbit hole. The years between 2020 and 2030 are actually going to define the city. The pressure is increasing.”

Also Read: India is obsessed with VIP number plates. Chandigarh govt earned Rs 1,200 cr in 5 yrs

Anatomy of chaos

Le Corbusier and Nehru had a dream. It was to design a city that was firmly planted in the emerging modernity of the 1950s. It was audacious because in the post-Independence decade, the temptation to celebrate India’s traditional architectural style was strong. Indian cities were steeped in their organic ancient-ness. Anything modern risked being viewed as sterile.

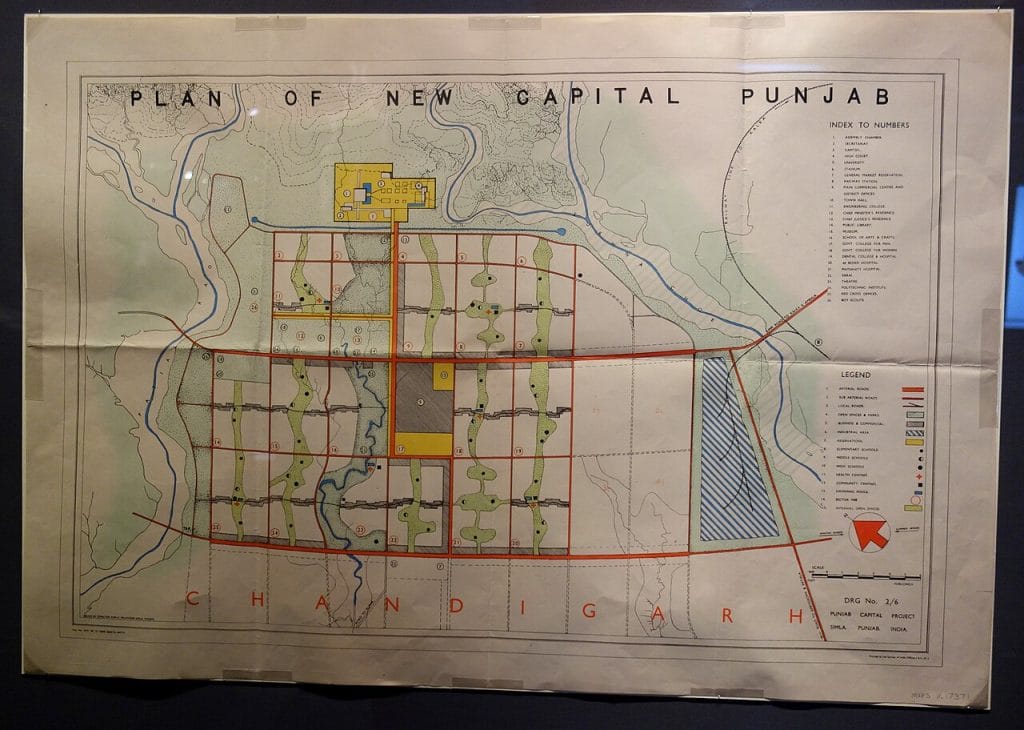

Le Corbusier saw the city as a human body, with separate sites for different functions. Chandigarh’s layout followed a grid pattern of self-contained sectors, each with neighbourhood markets, booths, and green belts. Shops were designed in a traditional mixed-use format with shops below and housing above.

Unlike Delhi neighbourhoods such as Lajpat Nagar or Greater Kailash, which were layered and improvised over decades, Corbusier planned Chandigarh in phases, with the government sector at the core and the city spreading outward, the density thinning toward the Shivaliks. Each sector was supposed to be orderly, walkable, and expandable.

“The city was intended as a symbol of democracy and modernity, designed without constraints from historical traditions,” said Kapil Setia, the former chief architect of Chandigarh.

But in this meticulously planned anatomy, there was a major oversight. The design did not account for the informal growth of the future. As more people arrived and commerce grew, pavements became bazaars and unplanned settlements started cropping up.

Slowly, Nehru’s Chandigarh faced the wrath of India’s frenzied urbanisation. Chandigarh residents have been fretting and fuming over street vendors’ takeover of sidewalks—something every other Indian city has—as well as slums. A class war has broken out.

In October 2025, the ‘City Beautiful’ declared itself ‘slum-free’ after years of demolition drives in which it reclaimed more than 500 acres of land valued at over Rs 20,000 crore. On 30 September last year, the UT administration demolished Shahpur, the last of the city’s 19 slum colonies.

Local news outlets streamed images of bulldozers at work, accompanied by breathless headlines such as ‘Chandigarh becomes SLUM FREE! Bulldozers run over migrant homes, LIVE visuals from Sec-38’ and ‘Chandigarh creates history by becoming India’s first slum-free city’. Others, however, were more sceptical. A Punjab Kesari report noted that “claims of making the city slum-free are nothing but hot air”, pointing out that an illegal colony had already come up next to Gwala Colony.

Chandigarh is a planned city, with no extra space yet vendors are being pushed onto footpaths and roads. This is starting to look like Delhi. There is no space left to walk. If this continues, Chandigarh will lose what made it different.

-Malkit Singh, president of the Manimajra Vyapar Mandal

Deputy commissioner Nishant Yadav told ThePrint that the administration had cleared the last five slum clusters over the past year, vacating around 60-70 acres, and shifted eligible families to Housing Board flats.

“We keep clearing those slums time and again because it is a continuous process. We have deputed 63 sectors in Chandigarh and 25 villages. We have dedicated staff officers in every sector and village who submit a fortnightly report that there is no new development of any slum in their area,” he said.

On 19 January this year, the DC said the administration was now targeting smaller encroachments, “whether they are in vending zones, on the sides of roads, or in green belts”.

One of the flashpoints is Manimajra, a neighbourhood on the northeastern edge of the city, about a 30-minute drive from the city centre. After demands from residents, it was designated as Sector 13 in 2020 and thus officially part of the grid. Unlike the postcard sectors, though, it is still frayed at the edges with unkempt roads and the haze of construction dust. It is still a neighbourhood that does not intimidate ‘outsiders’ with its affluence.

Now its vendors are the target of petitions, court cases, challans, hurried evictions. A not-so-perfect Chandigarh has been laid bare.

Chandigarh’s sidewalk war

It is 7 in the morning, and Manimajra market is already awake. Shopkeeper Malkit Singh has opened for the day, with loud Paytm alerts of “Rs 200 received, Rs 400 received” as customers pay for his famous tea, chhole, and parathas. But he keeps one annoyed eye on the vendors selling their wares on the footpath. Many have gone since an eviction drive in December, but some have already returned. The storefronts with glass doors and tiled floors still share space with makeshift stalls under tarpaulins covering crates of fruit, tea kettles, cheap winter wear, and stacks of boxes.

“I am not against the vendors, but they should be at the place where they have been allotted places,” grumbled Singh, who shifted from Patiala to Manimajra around 30 years ago.

He has seen the growth of Chandigarh from a city of dreams to a city of chaos.

“Chandigarh is a planned city, with no extra space yet vendors are being pushed onto footpaths and roads,” he added. “This is starting to look like Delhi. There is no space left to walk. If this continues, Chandigarh will lose what made it different.”

Chandigarh’s street vendor dispute is not new. It began years ago, a slow-burning conflict that residents blame on administrative oversight and alleged corruption. After the Street Vendors Act 2014 was passed, a survey two years later found there were around 22,000 vendors in the city. The administration designated around 40 vending zones for roughly 10,000 eligible vendors, including at the busy Shastri Market in Sector 22, but shopkeepers said the problem was only getting worse. This set off a round of protests from shopkeepers in 2017 who argued that vendors continued to operate in no-vending zones and blocked access to brick-and-mortar shops.

For years, Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) and shopkeepers appealed to the local administration to clear the pavements, but a turning point came in 2022. Malkit Singh, now the president of the Manimajra Vyapar Mandal, filed a case claiming the Street Vending Act was not being implemented in Manimajra and that a “mafia” had taken over.

Street vending is just one issue. It reflects deeper problems of capacity, planning delays, and changing urban realities

-Sanjay Tandon, former Chandigarh BJP president

Last May, the Punjab and Haryana High Court dismissed the plea, observing that the elite class still looked down upon their own countrymen doing small businesses as mafias and encroachers.

“Development of any city is on account of… the movement of the people from the villages to the towns and towns to cities,” the court said.

However, in December, the judgment was reversed by the Supreme Court, which gave the municipal corporation 48 hours to clear encroachments.

On 16 December, the Municipal Corporation carried out a city-wide drive to remove unauthorised vendors, focusing especially on Manimajra. By dusk, as many as 310 challans had been issued. Many street vendors were removed from the location and allotted space nearly three kilometres away, at the new vending zone near Chandigarh’s IT Park.

But, as was seen in other eviction drives, the vendors have not conveniently disappeared.

Back in Shastri Market, Mukesh Goyal, who has run a clothing shop for three decades and long campaigned against the vendors, acts as something of a local enforcer. It’s he who alerts the administration about unauthorised vendors. As he walks through the market with his hands clasped behind his back, vendors start to dodge out of sight. Everyone greets him. Several vendors bow with a respectful “Namaste, sir.”

Underneath the civility is simmering mutual resentment.

One of the vendors here is Khan Mohammed, who, along with his two brothers, was allotted space after the 2016 survey. Originally from Uttar Pradesh, the brothers have fresh winter wear from Ludhiana’s factories, selling lookalike versions of brands from H&M to Zara. Half-puffer jackets that cost thousands in brand stores go for Rs 600 here, without bargaining.

“Three jackets for 1000 rupees, one sweater for 200 rupees,” Khan shouted at the top of his voice, doing brisk business even though it was a Tuesday.

The brothers have emerged as major competitors for the shops that have been there for years.

“Jo hum meeti lagakar bech rahe hai, woh ye log cream lagakar bhi nahi bech pa rahe hai (What we sell in the rough, they can’t sell even after putting cream),” Khan said.

For Goyal, none of this is fair.

“We pay GST, income tax, garbage charges, every tax the government has asked for. The vendors sitting in front of us pay nothing, yet their sales are higher than ours,” he said bitterly.

The migrant question

The sentiment against vendors is also a manifestation of deeper anxieties about migrants taking over what was once envisioned as post-Partition Punjab’s promised land.

Both Singh and Goyal allege that most vendors come from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, or Nepal, and that a political-administrative nexus allows them to stay.

“Ye UP, Bihar walo ne sara kaam kharab kar dia hai,” Singh said, accusing migrants from UP and Bihar of “ruining most of the things.”

Now, doing business has become harder by the month for migrant vendors caught in the drive against ‘encroachments’.

After the Supreme Court’s order in December, the Verma family, originally from Uttar Pradesh, moved their paratha stall, Verma Bhojanalaya, out of Manimajra and into the new vending zone near Chandigarh’s IT Park. A decade of building a loyal clientele went down the drain.

“After we shifted to this location, our income has gone down from Rs 10,000 a day to Rs 2,000,” said Neeraj Verma, clanking his ladle on the hot tawa. His younger brother Dasrath also came to Chandigarh four years ago to join the burgeoning business. They have no plans to return to Manimajra, fearing detention and confrontations.

Chandigarh’s population stood at 10.55 lakh in the 2011 Census, and more than half, 6.86 lakh, were migrants. The largest numbers came from Uttar Pradesh, followed by Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, and Bihar.

“What has happened is not the elimination of slums, but their transformation into rehabilitation colonies and service-notified settlements. Calling the city slum-free erases this history and the continuing deprivation in these areas. Officially, there may be electricity and water connections, but on the ground, conditions are still slum-like

-KBS Sidhu, retired IAS officer

Many of these migrants, who’ve helped build the city, have always lived in informal dwellings but over the past two decades, the administration has bulldozed settlement after settlement, pushing many to villages such as Jagatpura on the outskirts of Chandigarh and Mohali, well outside the reaches of the city’s grid.

DC Yadav said the slum clusters came up on government land acquired during Chandigarh’s phased expansion in the 1950s. Large tracts were taken over as the city grew sector by sector, but some of this land remained undeveloped for years before it was plotted and converted into formal sectors. He linked the administration’s recent scorched-earth demolition drive to law-and-order concerns.

“Wherever there are slums, in the areas around it, cases of theft increase. Crime increases. Many of them are migrants,” he said, echoing the anti-migrant rhetoric that many politicians across India have repeated for years.

In recent months, the Punjabi-versus-pravasi sentiment has escalated across the state. After the murder of a five-year-old boy in Hoshiarpur, allegedly by a migrant shop helper, several village councils passed resolutions seeking to restrict migrants from buying land or working as vendors. Migrant groups such as the Bihar Foundation and the Purvanchal Association have issued statements warning of an “atmosphere of fear” and people being forced to leave the state.

Sanjay Tandon, a BJP leader from Punjab and the party’s former Chandigarh president, said that blaming migrants was misguided.

“Street vending is just one issue. It reflects deeper problems of capacity, planning delays, and changing urban realities,” he told ThePrint. “Migrants are part and parcel of the city.”

‘Conditions are still slum-like’

The Vermas live in Indira Colony, a low-income housing complex near the IT Park. Buildings are squeezed together, with little space between them, and there’s a small park shared by 40 buildings. They pay Rs 9,000 for a two-room apartment.

Another resident of Indira Colony, Om Pal, has built a matchbox-sized two-storey house for his family of five. He and his son, Praveen, came here from Haridwar and own a small fruit cart. They once sold their produce in the city, but after the vending zone disputes, he shifted to Indira Colony.

Pal has a licence — a simple white paper with little more than an issuing date — which he keeps tucked under a few rugs on the cart.

“I have to keep it with me, the administration can ask for it anytime,” Pal said. “We are hardly managing a living. Earlier, it was an advantage for us to be in Chandigarh. Now it is the same whether in Haridwar, Lucknow, or this city.”

Chandigarh’s ‘slum-free’ victory lap doesn’t hold up to scrutiny, according to KBS Sidhu, a Chandigarh-based former IAS officer who retired as Special Chief Secretary, Punjab.

“What has happened is not the elimination of slums, but their transformation into rehabilitation colonies and service-notified settlements. Calling the city slum-free erases this history and the continuing deprivation in these areas,” he said. “Officially, there may be electricity and water connections, but on the ground, conditions are still slum-like.”

From a planning perspective, he said, it is important to acknowledge that slums were first allowed, then serviced, and only later rebranded.

“Without recognising that trajectory, policy discussions remain dishonest,” he added.

The perils of success

Born as a template for setting up modern India’s urban future, Chandigarh was sold to everyone as an urban utopia of fresh air, greenery, and aesthetic design. Except it was never meant to be this crowded. It was planned for a population of around five lakh and is now home to more than double this number.

What was imagined as a compact, orderly capital steadily turned into a magnet for education, healthcare, jobs, retirement.

“Chandigarh’s tragedy is its own success,” said Rajnish Wattas, former principal of the Chandigarh School of Architecture.

The growth brought prosperity, but it also strained infrastructure. Housing costs have doubled over the last five years, even as liveability is no longer what it used to be. Residents place much of the blame on ‘outsiders’

In the near future Chandigarh will face traffic problems. There are cars coming from outside, and the city has itself so many moving cars. The city already faces parking problems

-Amit Kumar, Chandigarh municipal commissioner

For a weekend visitor from Delhi, Chandigarh is a gateway to cleaner air, fresh beer at breweries, and shopping at the famous Sector 17 market. It also “bears the weight of education and health from all neighbouring areas”, said Kapil Setia of the Chandigarh Citizens Foundation, a platform that focuses on finding solutions for the city’s inclusive development.

But for those who live here, this spirit of welcome is a mounting burden.

“In the near future Chandigarh will face traffic problems. There are cars coming from outside, and the city has itself so many moving cars,” said Amit Kumar, Chandigarh municipal commissioner. “The city already faces parking problems.”

It was once rare to get stuck at a signal but now it’s common to have to “cross in the second go”, said Vinayak, a resident of Sector 35A.

With over 15 lakh registered vehicles, and two lakh added in just the last five years, the much-vaunted grid is beginning to buckle especially without a robust intra-city public transport system.

“We often say the metro should have been planned 20 years ago. That delay is exactly why these problems feel unmanageable today,” said BJP’s Tandon.

Divides in the grid city

Not all sectors are created equal in Chandigarh. There’s a social hierarchy.

Aruna Chauhan argues that residents in the northern parts of the city still inhabit a well-preserved sanctuary, while those in the south have to constantly side-step street vendors and scrounge for parking space. This is a common perception.

“In the northern sectors, plot sizes run into six to eight kanals. Even sectors with relatively smaller plots still reflect elite planning. This immediately creates a hierarchy that is spatial as well as social,” Sidhu said.

Further out, in Greater Chandigarh, the contrast is even greater. The residents of Daddu Majra Colony complain about a rising heap of waste.

This neighbourhood is the Ghazipur landfill of Chandigarh, though much smaller in size. All the city’s garbage is dumped here, hidden behind a 25-foot wall built four years ago after residents protested.

Mahendra Pal, who grew up in Daddu Majra Colony, has watched the mountain of waste swell over the years.

“In the last 10 years, several people have moved to the villages of Mohali. It smells so bad, how can we stay here?” he said.

The mountain has stigmatised the colony, according to him: “Nobody wants to marry off their daughters to the village; people find it disgusting.”

Till a few years ago, rainwater mixed with toxic runoff would flow into the residential area.

“It used to be so bad that if you stepped into that water, there would be blisters on the body,” said another resident, Brajesh Kumar.

In Sector 41, the urban pressure has taken the form of class friction. With a careful balance of housing, markets, and gardens, it was meant to be the height of orderly living for the families who won their flats through the Chandigarh Housing Board’s lottery system decades ago. Now vendors in the market nearby have come to symbolise the end of that promise.

Every evening, RWA president Dharam Pal and 80-year-old resident TS Bhandari witness a familiar ritual: a municipal van shooing away illegal street vendors. The conflict dates back to 2017, when the administration allotted a temporary vending plot— opposite houses 2015 to 2032—in an area residents previously used for parking. It’s been a sore spot ever since.

“We were promised that these vendors would be moved to their designated areas, but till now nothing has happened,” said Pal. “When municipal vehicles come round, these vendors are moved, but a few hours later we see them back to the same spot.”

For Bhandari, whose house directly faces the vending zone, the memories of a tranquil neighbourhood are being drowned out by the chaos of the market. He brandishes a thick sheaf of papers—copies of every letter he has written to the administration to remove the vendors.

“Our neighbourhood used to be really peaceful,” he rued. “They drink alcohol, abuse each other and create chaos, this place is not safe for our children. Only a handful of us are left here. If this continues, we will be forced to move out.”

Bhandari doesn’t have the heart to leave his two-bedroom house yet, but the exodus has already begun. His own son has joined the wave of residents seeking the space, peace, and affordability in the satellite towns of Mohali, Panchkula, and Zirakpur.

Tri-City stopgap

While Bhandari’s son has moved to Zirakpur, Aruna Chauhan chose Mohali. Chandigarh’s flats were cramped, and soaring property prices had put a bungalow out of reach. In Mohali, she has the house and garden that would never have been within her budget in Chandigarh. In her new posh sector, where a 251-square-metre plot costs more than Rs 5 crore, she is finally happy. Her son can cycle safely without “miscreants” nearby.

Yet Chauhan, who settled in Chandigarh in 1995, still thinks deeply about the city she left behind. To her, the shift of middle-class families to the “Tri-Cities” is a symptom of a massive policy failure.

The reality is that Chandigarh, Mohali, Panchkula, and Zirakpur have become a single, codependent organism.

“The Union territory should be viewed as a city complex like Central London or Manhattan,” said Wattas.

However, these satellite cities have not just absorbed those who are priced out and fed up, but are also slowly inheriting the same stresses. Because the “Tri-City” functions as one unit, the problems of the core inevitably bleed into the periphery.

“The tri cities relieve some of the residential pressure out of Chandigarh, but create pressures in infrastructure and public services”, said Setia, sitting in the Chandigarh Citizens Foundation office inside a heritage building. He gestured toward the organisation’s symbol — an open hand — a nod to the vision of Chandigarh as an inclusive city.

But Setia himself has moved to Panchkula and commutes to Chandigarh for work.

“It was impossible to afford a comfortable living in Chandigarh,” he laughed.

Also Read: ‘Crowning glory of Punjab’: Why Chandigarh is a deeply emotive issue for Punjabis

A new masterplan

A new plan is on its way. The city is investing in a future that is consistent with Le Corbusier, even if the present is tense.

A new roadmap, the Chandigarh Master Plan 2031, is an attempt to double down on the architect’s vision while also tying up the loose ends left behind over the last seven decades.

The plan is ambitious, designed to accommodate a population of 16 lakh while focusing on the three biggest pain points: infrastructure, population management, and waste.

“For the first time, the city was clearly mapped into heritage zones, precincts, and buildings,” said Sumit Kaur, former chief architect of the Chandigarh Department of Urban Planning. “This gave legal backing to what must be preserved.”

Implementation, however, has been painfully slow. Though the process of drafting a comprehensive master plan began as far back as 2008, it took over six years of bureaucratic hurdles before the Ministry of Home Affairs finally notified the Plan in 2015.

Chandigarh’s tragedy is its own success

-Rajnish Wattas, former principal of the Chandigarh School of Architecture

Projects such as transforming Vikas Marg into a major commercial corridor and building 13 underpasses to ease traffic have finally stirred to life. However, there’s already been friction as well.

In August 2025, the city’s first “green corridor” project—an 8-km non-motorised transport route to connect the Capitol Complex to Sector 56—was abruptly scrapped. Despite being a flagship project of the 2031 Plan and seeing 200 trees felled for its construction, the Heritage Committee ultimately sided with Sector 10 residents who argued that the corridor was unnecessary. The committee concluded that introducing cycle tracks into green belts would undermine the “serene environment”.

While the plan takes into account the city’s natural and architectural heritage, it does little to address chinks in the “Tri-City” system. Architects argue that the city’s design is one of the world’s best, but that it needs better coordination with Mohali and Panchkula on infrastructure planning.

One thing they all agree on. Policy is letting down Le Corbusier’s dream.

“The character of the city is not to be blamed, there are no right policies to manage a city like Chandigarh,” Gandhi said.

For Kaur, the bigger tragedy is that the Chandigarh model was never replicated.

“We should be building more Chandigarhs,” she said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Every good thing in India becomes worse over a period of time and Chandigarh is no exception. This is the speciality of our socialist country famous for corruption and incompetence.