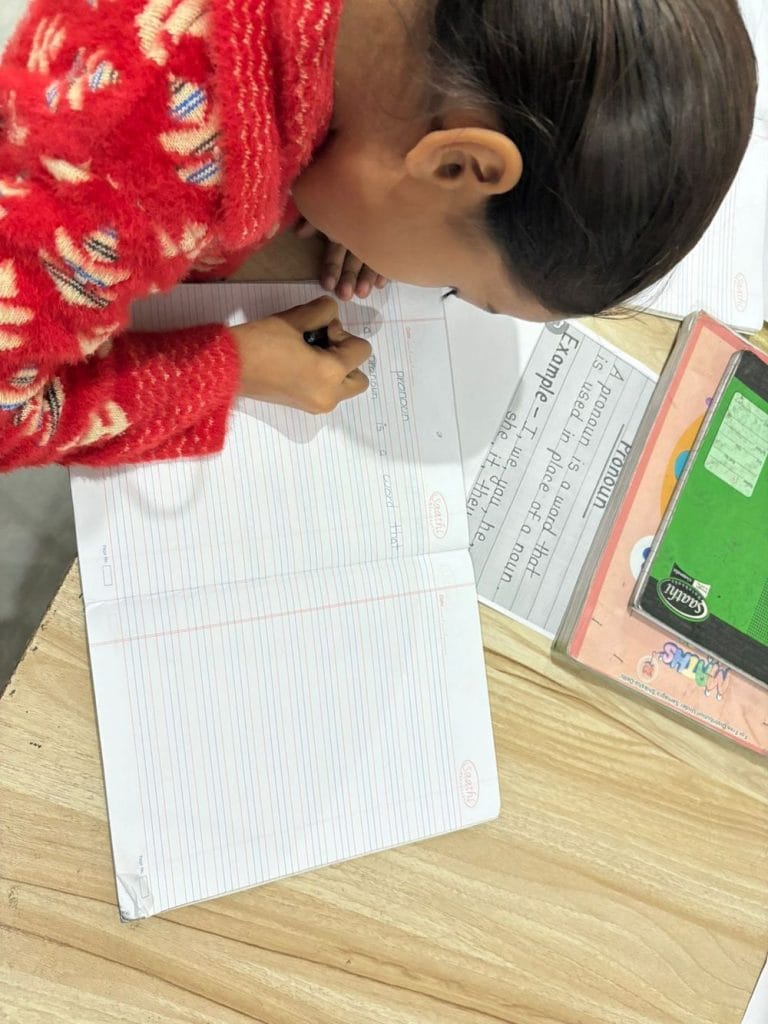

New Delhi: A Class 5 student at a Delhi Public School squinted at the notebook in front of him, trying to write the days of the week in English. For Tuesday, he wrote an ‘f’ instead of a ‘d’, then rubbed it out and tried again. He is still struggling with words his classmates mastered years ago. His parents never learned to read or write, but he is catching up. Much of that work happens after school hours in a Vasant Kunj basement.

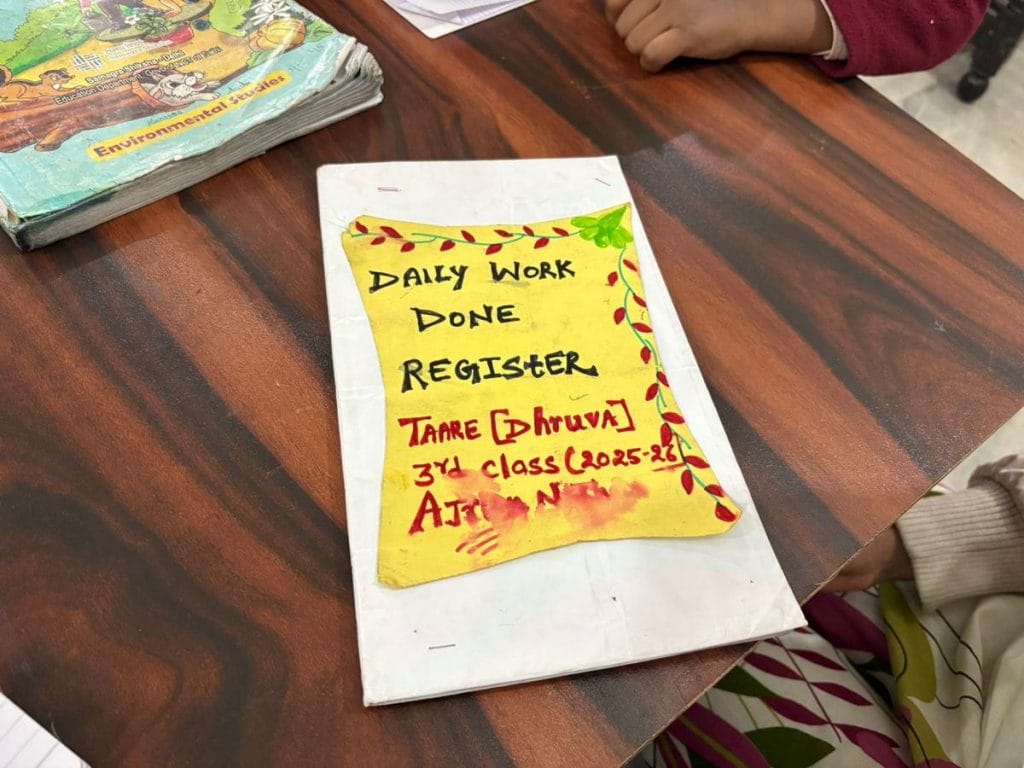

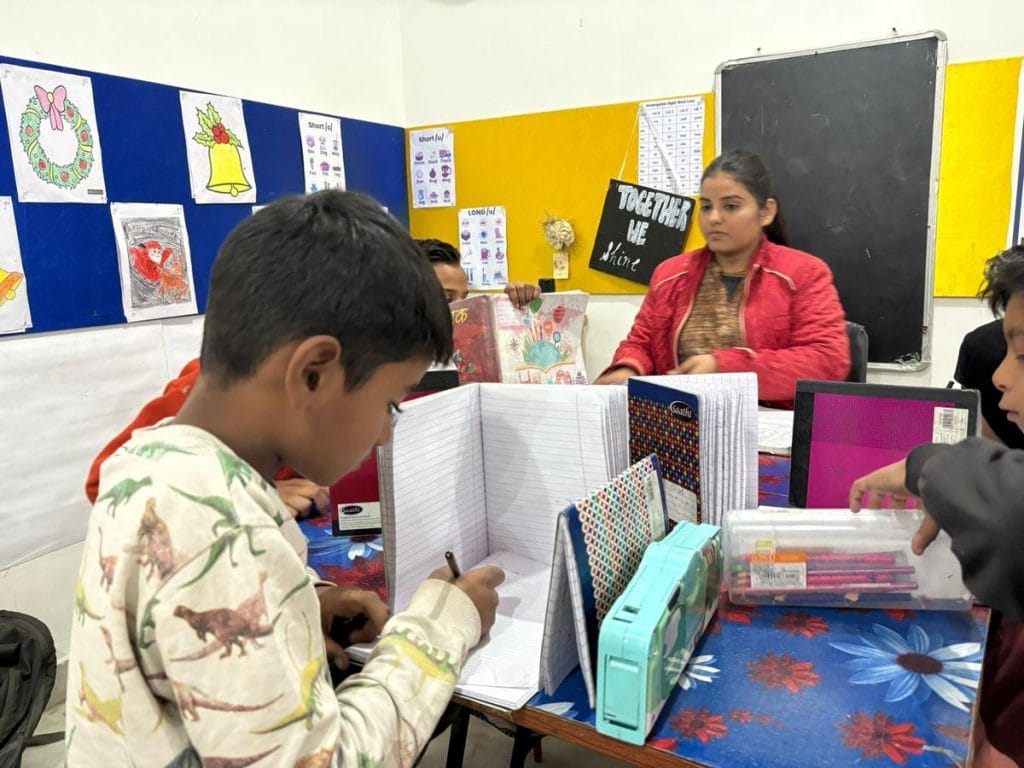

“Apple, ball, cat,” he chanted along with other children at Taare Education Foundation, a second school for EWS children studying in private institutions. Most of the children around him were in Class 2, though two others were in Classes 6 and 7, all working through the same lessons.

An ambitious move to integrate children from low-wage families into Delhi’s elite private schools hasn’t broken down classroom and class divides as intended. Fifteen years later, forming basic English sentences remains a struggle, classroom seating is loaded, and a parallel, separate-but-equal system has taken form.

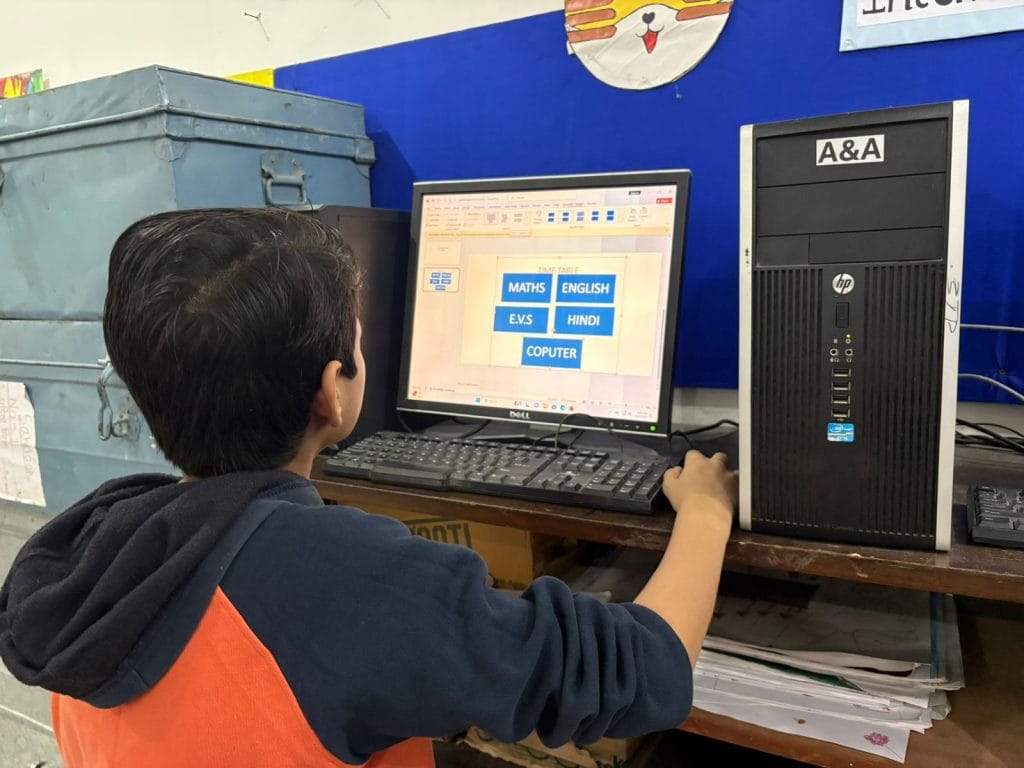

To bridge the gap between the lofty goals of the Right to Education Act’s 25 per cent EWS quota and its patchy learning outcomes, a small number of after-school ventures have sprung up across the city in recent years. These include NGOs such as Samagraa and Taare Education Foundation, where children undertake remedial lessons without stigma and shame.

“Many children arrive in higher grades without even the basics, and schools often overlook this. We rebuild their foundation so they can stand shoulder to shoulder with their peers. We need special educators for these students in every school, but schools don’t hire them,” said Preeti Devasar, 52, director and co-founder of Taare along with Puja Sharma. It was established as an NGO in 2023 to help EWS students already enrolled in private schools keep pace academically, navigate social barriers, and claim the dignity the policy promised them.

The policy’s shortfalls start at the admission stage. According to the Delhi government’s 2022-23 outcome budget, 35 per cent of the roughly 40,000 EWS seats reserved under the RTE Act in private schools remained vacant until September 2022. The picture was little better in earlier years, with fill rates of 67 per cent in 2021-22 and 62 per cent in 2020-21. Furthermore, the RTE Act mandates free education only until the age of 14, unless the school is on government land, which means that parents are often handed a fee bill they are unable to pay.

Inside classrooms, exclusion often takes subtler forms, with students claiming they are singled out by teachers with remarks such as, “tum to EWS se ho”.

In the city’s profit-driven schools, money becomes an impediment for EWS students even when their education is technically supposed to be free. In August 2025, the Delhi High Court sought responses from government on a PIL alleging the “systematic exclusion” of EWS students by forcing them to buy expensive books and uniforms. The Supreme Court in November also criticised government inaction on a PIL seeking internet access for poor children left offline during school closures triggered by pollution.

The introduction of the EWS category has disrupted a status quo, where the system was neatly divided into two worlds: children who could afford private school fees and those confined to government schools.

When I was in Class 2 or 3, I could talk to general category children. But as I grew older, I didn’t have a single friend from that group

-Navya, Class 11 student in DPS Vasant Kunj

Private schools, however, argue that government reimbursements fall well short of actual costs. The resentment this breeds often trickles into classrooms, some teachers acknowledged, though they declined to say so on record.

The goal of true assimilation has not received the priority it requires, according to Shailaja Chandra, a retired Union secretary and former chief secretary who was part of the 2011 review committee for the Delhi School Education Act and Rules 1973.

“In Delhi, the scheme has not failed, no, but neither is it a major success story,” she said. “The admissions of EWS children have increased, yet without monitoring and outcome-based rating of individual schools, the law’s purpose remains unfulfilled. A major gap is the absence of longitudinal tracking which is essential to measure assimilation. To date, no detailed study has assessed the benefits gained since the law’s enactment. If the School Education Secretary were to evaluate state-level implementation, states would likely begin tracking outcomes, and private schools would become more accountable.”

ThePrint tried to contact the Directorate of Education via email and through an in-person visit, but received no response.

However, Yogesh Pratap, former deputy director of Education (Private Schools Branch) argued that Delhi had implemented the EWS scheme more effectively than other states.

“In Delhi, both small and large schools have adhered to the guidelines with great diligence. If a school fails to follow the rules, it is initially issued a notice, and continued non-compliance has led to the withdrawal of recognition in several cases. As a result, most schools are now well aware that compliance is mandatory,” he said.

Also Read: Inside Oscar-nominated Homebound boys’ village in UP—a heavy burden of memory

Doing what schools won’t

Just two days into Navya’s first year at DPS Vasant Kunj under the then newly minted EWS quota, a note came home from her teacher: “What is this drawing? Teach your child how to draw.”

Navya is the daughter of a domestic worker employed by Preeti Devasar, but the activist has always treated her as her own granddaughter. The note made her furious.

“The child had just started reading. And for her creativity, you write this? Do you even know she comes from an EWS background? Who did they write the note for? Her parents don’t understand English,” said Devasar.

The incident, over a decade ago, stoked a fire in her to intervene in a system that assumed parental capacity that didn’t exist, and punished children for it. Notes from school rarely translated into support. More often, they became scolding at home. If these children were to keep pace with peers who had grown up with privilege, Devasar realised, the basics had to come first—English and maths.

And so, in 2012, long before Taare had a name, Devasar left behind a successful career as a merchandiser and began teaching 15 children of society guards and other workers inside her own home. From a handful of students, it has grown into an NGO and learning centre that supports over 110 children, mostly at the primary level, though some older students attend as well.

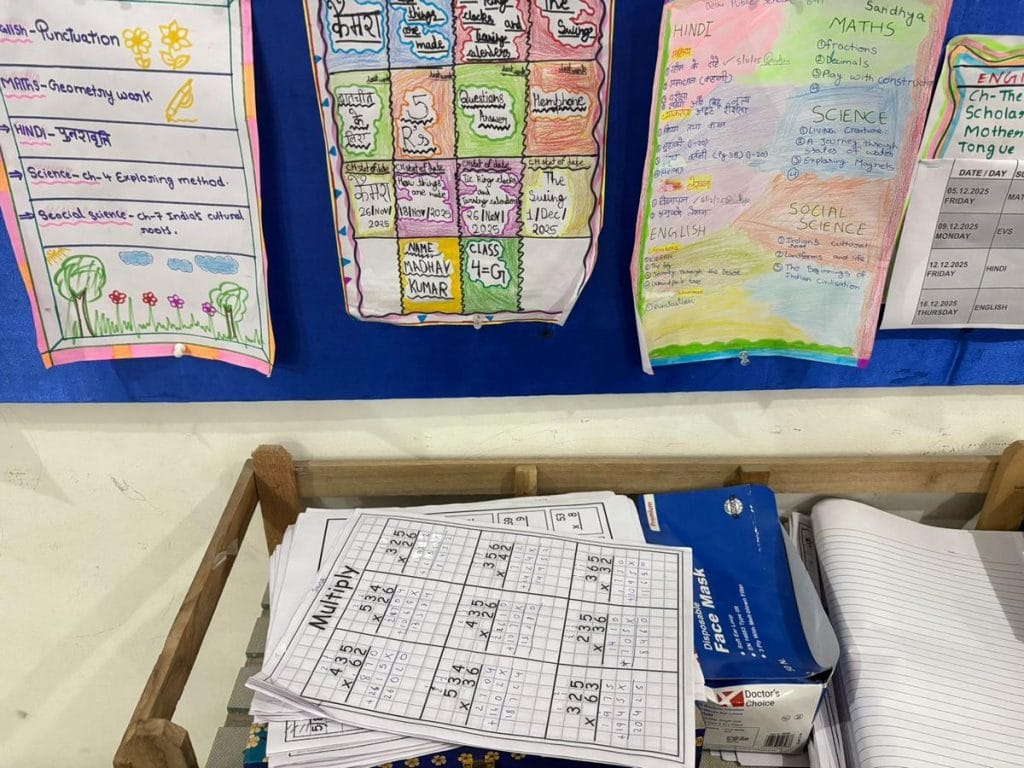

From 3-5.30 pm on weekdays, the cavernous basement school comes alive with children clustered around different work tables. Fourteen permanent teachers, as well as six volunteers, guide them as they trace letters in notebooks and sound out words aloud until they stick. When there are ‘tests’, they hold up notebooks like shields to stop each other from cheating.

The children call Devasar their Badi Maa, a role she inhabits with quiet devotion. She sometimes attends PTMs on their parents’ behalf, and never misses a chance to gently remind them that they are loved.

Many children arrive in higher grades without even the basics, and schools often overlook this. We rebuild their foundation so they can stand shoulder to shoulder with their peers. We need special educators for these students in every school, but schools don’t hire them

-Preeti Devasar, co-founder of Taare Education Foundation

Whenever schools send threatening notes to parents, warning of suspension or accusing a child of misconduct, Devasar acts as their representative. It’s she who storms into these meetings, defending the children at the top of her voice. But the social segregation built into private school classrooms has only hardened over time.

“When I was in Class 2 or 3, I could talk to general category children. But as I grew older, I didn’t have a single friend from that group,” said Navya, who is now in Class 11.

ThePrint emailed the principal and counsellor of DPS Vasant Kunj, but received no response.

It’s tougher for children who were older when they entered private schools. Without psycho-educational assessments or academic bridging, many fall behind or drop out. A 2017 study by the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) found that in 2011, the dropout rate was around 26 per cent, falling to 10 per cent in 2014, but showing “no major progress after that”. The study cited a school where 15 of 19 students identified as “slow learners” were from the EWS category, attributing this to weak English skills and limited parental support.

Organisations such as Taare are now stepping in where schools generally do not by counselling parents, assessing children realistically, and addressing behavioural issues. Devasar cited the case of Chinu, an EWS student at Chinmaya Vidyalaya in Vasant Vihar. Brought up in an abusive home, he had developed a habit of taking things without asking, leading classmates to label him a “chor” (thief). With regular counselling at Taare, she said, his behaviour has improved.

To build confidence and a sense of belonging, Taare has also turned to sport. When football and cricket coaching began, parents called in large numbers to enrol their children. On Instagram, Devasar runs a series called Taare Times, showcasing children playing and doing sports—with her joining in too.

“At school, we play other games, but I had never played football before. This was my first time. At first, I was a little scared, but everyone plays together here—even the teachers join in and the coach teaches us,” said a Class 4 student.

Invisible and visible lines

Rooh grew up straddling two very different worlds. While her classmates unwrapped fancy pencil boxes, glittering pens, and lavish gifts, she watched from the sidelines, acutely aware of what she lacked. In her single-room home in Nizamuddin, Delhi, she saw her parents working tirelessly, sacrificing sleep and comfort to ensure she had an education.

Her father worked seasonally, selling fruits from a cart, especially during winters and Ramzan. Her mother, meanwhile, worked as a dispenser at an NGO called Hope Project.

From KG onwards, Rooh, now 19, attended Mater Dei School, a convent school in south Delhi. Money was a constant worry.

“One book cost Rs 300. Some are even Rs 500. Not exactly affordable,” she said.

Her mother Ishrat enrolled her at the school on the advice of her own teacher.

“She told me, ‘Yahan ka kachra bhi kamyab hota hai (Even the waste from that school becomes successful),’” Ishrat recalled. “That line stayed with me.”

I didn’t remove my daughter from the school because I kept believing what my teacher had told me—that even the worst-off students from that school succeed

Ishrat, parent of former EWS student Rooh

Even as other EWS students dropped out because families could not afford uniforms or expensive books year after year, Ishrat persisted. When Rooh reached Class 8 and the school informed them that the EWS quota no longer applied, they scraped together fees to keep her enrolled.

Ishrat recalled one particularly humiliating incident. The principal once told them that if a family owned a washing machine, a TV, and a fridge, then they could not be poor.

“Who doesn’t have these things today? Sometimes you have to buy them out of necessity,” she said. “It hurt a lot. But I didn’t remove my daughter from the school because I kept believing what my teacher had told me—that even the worst-off students from that school succeed.”

But Rooh struggled academically. She scored zero in Maths in Class 3, and her grades stayed low for years. Her performance improved in high school, but at a cost. For Classes 11 and 12, her parents enrolled her in commerce tuition classes, paying over Rs 2,000 a month with help from relatives. Ishrat borrowed money and took loans from her job. At the time, her salary was only Rs 5,000 a month.

Now, Rooh is pursuing a BA Political Science at Shyama Prasad Mukherjee College in Punjabi Bagh. She gives home tuitions, earning around Rs 8,000 a month, of which Rs 5,000 goes to her family.

“Right now, my dream is to secure a scholarship and study at an international university,” she said.

For some students, the EWS divide was enforced physically. A 15-year-old student at DPS Vasant Kunj said that the school created a separate section for EWS students last year.

“Now I’m in 9th, section B. My classmates are all like me, EWS,” said the student, who repeated Class 8. Teachers paid less attention to students in this section, he claimed; even if a student slept during class, no one reprimanded them, unlike in other sections. Interactions with non-EWS students were limited but one conversation stuck with him. When he casually asked a batchmate where he lived, the reply was, “Mai vahan se hun jahan tu kabhi phunch bhi nhi paayega (I’m from a place you could never even reach).”

The following year, he unexpectedly ran into the same student outside the tuition centre he attended. Surprised, he asked him what he was doing there. “My house is nearby,” the batchmate replied.

“That day, I realised I had eventually reached the very place I was once told I could never reach,” he said. “And it wasn’t as far away as it had once seemed.”

Some teachers, however, say they do pay attention to the emotional and social challenges EWS students face. Susha P Roy, a teacher at Evergreen Public School, said EWS students often suffer from a sense of inferiority, reinforced by visible differences in their stationery or tiffins.

“To address this, the school consciously focused on empathy and sensitisation. The discussion began with the idea of uniformity—why uniforms exist and why equality is essential in a school environment. Students were made to understand inclusiveness and the importance of seeing everyone as equal, regardless of financial background,” said Roy.

Land and lofty goals

In the first flush of Independence, the Government of India set out to encourage a proliferation of “charitable” schools and hospitals. One way to do this was cheap land. At a meeting chaired by the finance secretary on 10 June 1949, it was decided to allocate public land to educational and health institutions for rates of Rs 2,000 to Rs 5,000 per acre, a fraction of the market rate even then.

“The test should be that the institution should be run for the good of the public without any profit motive,” said the policy.

Subsequently, allotment letters and lease deeds for schools set basic conditions for schools to run as secular, non-profit institutions serving the public, later reflected in the Delhi Development Authority’s Nazul Rules. One such condition for allotment of land at concessional rates was that the school would reserve up to 25 per cent of seats for low-income students.

“Initially, enforcement was weak and unclear,” said Ashok Aggarwal, advocate and founder of Social Jurist, a Delhi NGO advocating children’s education rights since 1997. “In 2002, we obtained a list of 265 societies that had received land. Sample allotment letters fell into three categories: one specifying 25 per cent reservation, one leaving the percentage to be decided by the government, and one with no mention of reservation at all.”

Between the 1950s and 80s, hundreds of schools benefited enormously from the land allotments, but the “charitable” part of the equation often fell by the wayside.

The scale of non-compliance came into public view with a 2004-05 Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report, which found that “133 out of the 381 societies which had been allotted land at concessional rates failed to provide the stipulated 25 per cent reservation for children from the weaker sections as of March 2004”.

In its audit of 24 schools, CAG found that 19 schools extended no reservations at all, while the remaining five did so well below the mandated percentage. This, said the report, not only defeated the social purpose of the policy but also caused the DDA a revenue loss of about Rs 125 crore due to the concessional rate.

The admissions of EWS children have increased, yet without monitoring and outcome-based rating of individual schools, the law’s purpose remains unfulfilled. A major gap is the absence of longitudinal tracking which is essential to measure assimilation. To date, no detailed study has assessed the benefits gained since the law’s enactment

-Shailaja Chandra, former chief secretary of Delhi

Following sustained legal pressure and public mobilisation, the first formal directive mandating 20 per cent EWS reservation in private schools was issued in April 2004.

“We mobilised people in resettlement colonies like Hastasal. Within ten days, 1,750 applications were filed in the High Court, demanding that the government publish the list of schools,” recounted Aggarwal, who was at the forefront of the fight. “It succeeded because there was genuine public engagement and commitment.”

Income ceilings for eligibility were set and revised over the years. After multiple changes, the EWS income limit for private school admissions in Delhi now stands at Rs 5 lakh.

When RTE hit the ground

When Shailja Chandra was appointed by the Delhi government to head a review committee to align the Delhi School Education Act and Rules with the RTE mandate in 2011, a number of questions nagged at her. What would “integration” look like in practice? How could EWS children compete with affluent peers and find their place in society?

As she consulted a wide range of stakeholders—principals, NGOs, educators—resistance bubbled to the surface. Many school heads doubted the policy could work at all.

We give them access to air-conditioned classrooms, sports teachers, books, and uniforms. The funding shortfall is absorbed by the school and, indirectly, by other fee-paying students. Schools face financial strain

-Priyanka Gulati, principal of Evergreen Public School

“RTE became a major topic of discussion across Delhi—seminars, workshops, talk shops—with a shared focus on providing disadvantaged children the opportunity for early integration and support. I was deeply involved in guiding the system, explaining how to apply and how admissions would work. At that early stage, no one had moved beyond Class 3 for the quota,” she said.

Compliance did not come easily. Schools initially resisted, even trying to turn fee-paying parents against EWS admissions by branding these children as “bad”. Even the NCPCR report noted that some principals held the belief that EWS students were “more prone” to starting fights, using abusive language, and “stealing stationery items such as pencil box or pen.”

But the momentum was already there. Chandra recalled that in 2013-14, even though she held no government position, drivers and guards in her neighbourhood often approached her for help filling forms, obtaining income certificates, and securing admissions for their children under the EWS quota.

She recounted that some families told her, “When both parents are working, who has the time to deal with the jhanjhat (hassle) of getting an income certificate?”

Over a decade on, the system is still riddled with holes.

Shikha Sharma Bagga, a Supreme Court advocate, said the system lacks checks to ensure that only genuine EWS families benefit. Fake affidavits and Aadhaar misuse allow well-off families to exploit quotas, while “honest parents navigate a confusing portal where nearby schools often appear far away.”

Quality education remains a distant dream for many EWS students, she added, because of the cost of uniforms, private publishers’ books, and digital devices. These expenses, she said, far exceed families’ annual incomes, making “the scheme a mockery for poor and destitute children.”

Also Read: New British boarding schools are here. The latest accessory for India’s rich

Adding value

In Delhi’s private schools, several principals argue that EWS inclusion is an expensive business.

“We give them access to air-conditioned classrooms, sports teachers, books, and uniforms. The funding shortfall is absorbed by the school and, indirectly, by other fee-paying students. Schools face financial strain, especially since regular fee hikes are tightly regulated in Delhi,” said Priyanka Gulati, principal of Evergreen Public School, Vasundhara Enclave, which has 450 EWS students.

Government reimbursements, nonexistent before 2012, were gradually introduced and calculated on the basis of per-child expenditure in government schools. The reimbursement stands at around Rs 2,242 per child each month.

The central government does not provide a separate budget for the RTE’s EWS quota; funds flow indirectly through Samagra Shiksha, an integrated central sector scheme launched by the Ministry of Education in 2018. States reimburse private schools from these grants.

A sore spot among many schools is the reimbursement cap for institutions on government land. Such schools receive EWS reimbursements for only 5 per cent of intake, compared with 25 per cent in schools on private land.

“We keep requesting repeatedly to increase the reimbursement; 5 per cent is far too little,” said Jyoti Arora, principal of Mount Abu Public School in Rohini. For non-government land schools, reimbursements stop after the 8th grade, leaving higher classes unfunded.

Another common complaint is delayed payments.

“Reimbursement delays of up to a year are common, creating a two-year dependency cycle,” said Bharat Arora, president of the Action Committee of Unaided Private Recognised Schools, which represents private schools on EWS-related issues in Delhi. He added that the provision for uniforms and textbooks—Rs 1,100 and Rs 1,490 respectively—falls well short of actual costs.

Despite these woes, however, Jyoti Arora said EWS students are performing exceptionally well in her school, with two even part of the national archery team.

“I am planning to create a list of students from EWS backgrounds who studied at our school and are now doing well in their careers. Their success will serve as examples and help us assess the effectiveness of the policy,” she said.

That such a list doesn’t exist and success stories haven’t been celebrated is telling.

Back at Taare, one of the teachers is Neha, 22, who herself grew up in an EWS household. A friend told her about the opportunity to teach there.

“I don’t want these kids to face the same struggles I did—being made fun of, struggling with English,” she said, surrounded by second- and third-graders diligently working through an assignment of new English words she had just handed out. “Today I’m capable, but I want them to reach that level earlier.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)