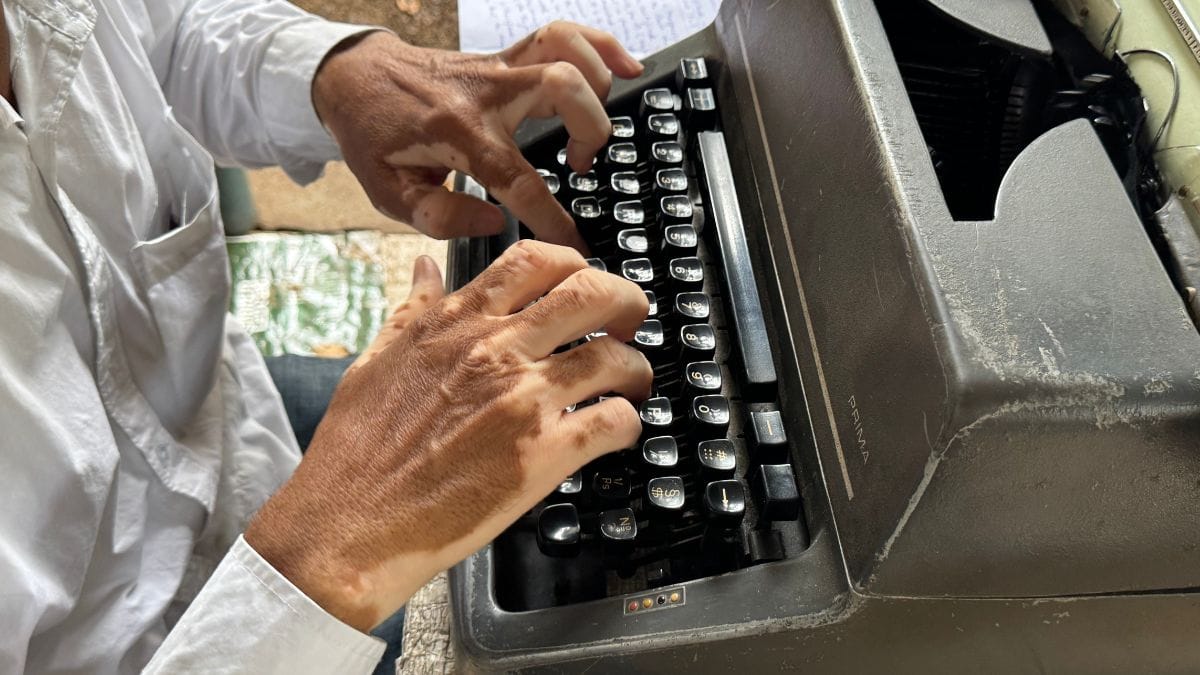

Coastal Andhra Pradesh: In a stuffy Andhra Pradesh courtroom, the stenographer clatters the keyboard furiously, trying to keep pace with the proceedings. “Write submitted, not said,” the judge snaps at her. But everything stalls until the frantic typing stops. The lawyer stares blankly. The witness rubs her hands, annoyed. A few people doze on colonial rickety benches. The system has to wait for the typewriter to stop.

This is how most Indian courtrooms still function—paper-heavy, largely manual and moving at a glacial pace. But a small AI revolution is underway. Not driverless cars, not sapient robots, not human-less surgeries.

AI is taking baby steps in India’s courts and making it count.

A few courtrooms away, Judge Shireen Sultana speaks into the mic. And the proceedings instantly appear on her desktop screen. “Next case, please,” she murmurs. The clerk tosses one file aside and picks up the next. Within minutes, the room begins to empty—case closed, orders passed. Justice moves fast here. An AI tool has made it possible.

In the hallways of the district court in Andhra Pradesh, everyone is talking about Judge Sultana Shireen’s courtroom—and how quickly the crowd empties. She has created a buzz as the only judge and the only woman using AI in the court. Now, everyone wants to follow her.

The backlog of 50 million pending cases across the country’s courts will take over 300 years to clear. And the real cost of this delayed justice is borne by helpless citizens who spend years entangled in court cases, putting their lives on hold.

Over 4,000 courts across nine states have adopted AI—that’s still just a fraction of the vast judicial system. From tools like ChatGPT to Perplexity, stenographers, typists, and lawyers are using AI for research and grammar. But a new entrant—Adalat AI— has gone a step further. Armed with legal vocabulary, this AI tool is changing the dynamics of courtroom proceedings. Stenographers have now taken a backseat as AI is transcribing court proceedings in real time.

The tool is the brainchild of Supreme Court lawyer Utkarsh Saxena and AI engineer Arghya Bhattacharya. With their expertise in law and technology, they built a tool to make justice faster.

“The court systems are broken—delays and backlogs shape everything. The processes and systems are outdated—manual, paper-based and extremely clerical. That’s really where Adalat AI was born. Someone needed to automate these processes, unclog the pipes and get the system flowing again,” said Utkarsh Saxena, a Harvard graduate. It was in 2023 that Saxena met Araghya Bhattacharya, an IIIT-H graduate, and together they founded Adalat AI. Through social impact funding, including CSR foundations and fellowships, the duo’s project was set in motion.

And high courts are slowly opening up to the use of AI in courtrooms. The Kerala High Court has mandated the use of Adalat AI for transcribing witness depositions in district courts, citing the need to tackle “procedural delays” in India’s legal system. Bihar is next in line, with some judges already adopting the tool. The AI tool has now gained such traction that it features in the official circulars of several state judicial academies. Still, some of the older generation of judges remain resistant.

“The primary use of Adalat AI is converting speech to text. Earlier, judges had to depend on stenographers or typists for dictation and transcription, which took a lot of time—especially with multiple rounds of corrections,” said NG Dinesh, a sitting judge and registrar, computers, at the High Court of Karnataka. “With Adalat AI, transcripts are generated in real time as the judge speaks. The tool also saves the audio, so typists can review and make corrections later without returning to the judge’s chamber,” he added.

The court systems are broken. The processes and systems are outdated—manual, paper-based and extremely clerical. That’s really where Adalat AI was born.

– Utkarsh Saxena, co-founder, Adalat AI

Also read: Don’t rely on AI, Google mid-argument—Punjab & Haryana HC warning divides legal practitioners

Handwritten notes to AI

A 34-year-old judge in Patna district court handles the work of three people—a stenographer, deposition writer and the work he has been appointed for. A4 sheets lay scattered across his table, filled with hurried, uneven handwriting—testimonies, depositions, orders.

Years of long hours, hunched over high wooden chairs have taken a toll—robbing him of work-life balance, peace and leaving him battling with spondylitis.

“We don’t have a stenographer. Not even a deposition writer,” he said. “Those are rare. Maybe some senior additional judges get one—but not us.”

This isn’t his first stint as a judge. Earlier, during a posting in Patiala, he had the support of a stenographer.

“There, I only had to correct the drafts,” he recalled. “It was hectic, yes—but it spared me from writing every word by hand.”

The situation in Bihar is a snapshot of how broken the legal system is—where judges are forced to don multiple hats: Scribe, writer, and adjudicator. It affects how cases are handled and the delays in providing justice.

Last year, during his posting at the Hajipur district court in Bihar, the judge witnessed his own ‘tareek pe tareek’ moment. A key witness in a forgery case had taken over a dozen trips to the court—but the judgment never came. One day, fed up, he simply walked away.

“He came to me and said, ‘Sir, I don’t even want my money anymore. Just drop the case’,” the judge recalled, laughing. “And then he left.”

We think of ourselves as the plumbers of the court system—using AI to automate the clerical and manual work, so that judges and court staff can focus on what actually matters.

– Utkarsh Saxena, co-founder, Adalat AI

But even the judges can’t do much but succumb to the pressure. There are days when almost ten witnesses turn up in a single day. These are people who have travelled far, left their work behind, and spent money on buses and autos just to get here. “You just can’t ask them to come back another day. So, we push through. No matter how long it takes. We skip meals and finish,” he said.

The system itself makes legal work even harder, especially in the Hindi-speaking states.

“We’re trained mostly in English, but all depositions are to be written in Hindi. When you’re writing fast, the handwriting slips. And if you’re writing fast in a language you’re less fluent in, it gets worse,” he said.

He recalled, quite embarrassingly, how a judge called him several times a day just to understand the deposition he had written last year. “Sometimes they take photos of the handwritten notes and send them to me on WhatsApp, asking, ‘Bhaiya, what does this say?’”

But now, AI has lifted the weight. A black mic protrudes from his desk, taking in every word and transcribing them onto his rugged old desktop. Now, he skims through the text, makes some corrections, and he’s done.

Earlier, he would dispose of four cases a day, but now, the number has gone up to eight.

Also read: DY Chandrachud is right about using tech in courts. Learn from Germany’s IBM AI assistant

Resistance to tech

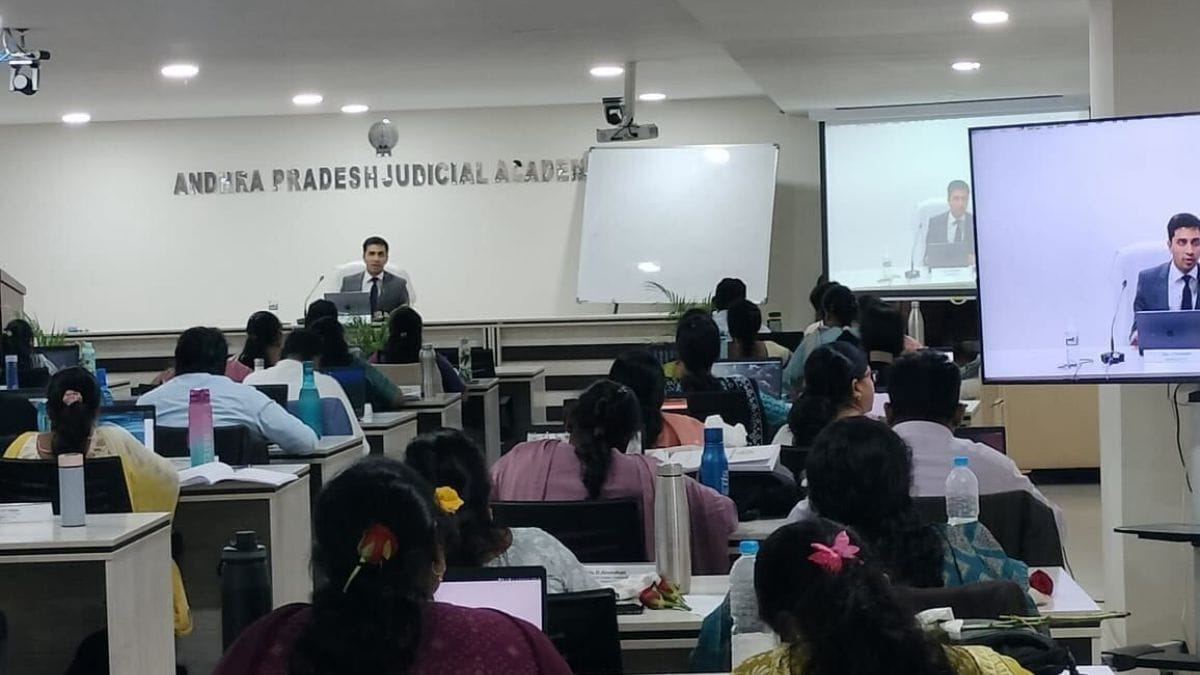

Behind this comfort of AI lies a tough struggle to convince stubborn judges to adopt the technology. During a training session in Karnataka, four judges sat in the corner of the room—arms folded, eyebrows furrowed. Parth Maniktala, the chief legal officer at Adalat AI, was on a mission to convert the judges to AI geeks. But all he met was with quiet resistance.

“They kept shaking their heads,” Maniktala recalled. “‘This won’t work for us,’ they said. ‘Not in real courtrooms.’”

The resistance and doubts took different turns. They started speaking rapidly into the mic, to prove that AI couldn’t keep pace with real courtroom speech.

“They were throwing challenges at me,” Maniktala said, with a loud laugh. “Talking fast, mixing legal terms, trying to confuse the system. But it was 95 per cent accurate all the time.”

But after the session ended, he didn’t give up. Instead, he sat with each of them separately. He guided them through every feature again—and allowed them to test the platform themselves.

“We are here talking about judges who didn’t even know how to update Google Chrome. In one case, a judge was speaking into the mic without knowing that his system was not connected to the internet,” said a trainer who did not wish to be named.

A preliminary training session in Kerala—meant to assess whether AI could be used in courtrooms—ended up paving the way for a sweeping nod to the platform. And that was after Adalat AI rolled out an updated version of Malayalam—the language used to write witness deposition and other proceedings in Kerala.

During the initial trials, the AI didn’t understand the language fully and produced transcripts riddled with errors.

“It was seen as a way forward to have a digital ecosystem, and everyone was on board for it,” said a senior judge from Kerala.

Soon, all the district courts across India that were using AI had their dedicated WhatsApp groups. All the judges and court staff from the district were members. These groups served as customer care channels where judges post their queries.

“The sub-groups are for interactive support. Judges post real-time questions, share feedback, or raise issues there, and the Adalat AI team proactively provides support and clarifies any doubts/queries,” said Maniktala.

The idea was to reduce clerical burdens and make judicial work more productive and efficient. To achieve that, the platform brought on native language experts in several states where transcription accuracy depended heavily on regional dialects.

The journey to build the platform was a personal experience for Utkarsh Saxena, who sought out Arghya Bhattacharya, an IIIT-H graduate.

Also read: Using AI tools in judicial process can improve justice delivery, but amplify biases: Report

Unclogging the drain

Like many fresh law graduates, Saxena stepped into criminal law. He wanted to stay close to ordinary people and their everyday struggles. His journey began as a law clerk at the Supreme Court of India, and he has practised in courts across the country. He has taken on landmark cases, including petitioning the Supreme Court to legalise marriage equality.

From Harvard to Oxford, Saxena immersed himself in rigorous academic research. But his idealism soon met the harsh realities of the courtroom.

“I got a rude shock,” he said. “The process itself has become the punishment. I realised you don’t count your time in court in years—you count it in decades.”

And that led to several sleepless nights and brainstorming on how to use technology to streamline these issues. Saxena’s experience across the legal system helped him identify one of the most persistent issues plaguing Indian courts: The severe shortage of stenographers and the urgent need for accurate transcription. Every courtroom requires detailed records of proceedings, yet less than 10 per cent have skilled stenographers.

“Someone needed to automate these processes, to unclog the pipes and get the system flowing again,” said Saxena. “We think of ourselves as the plumbers of the court system—using AI to automate the clerical and manual work, so that judges and court staff can focus on what actually matters.”

The challenge of the courtrooms was not limited to only transcription but also lingual diversity.

That was when Saxena met 27-year-old Bhattacharya in a ‘Gen AI’ WhatsApp group—a community of reputed AI engineers. It was there that Saxena posted about looking for a co-founder proficient in AI, technology, and linguistics. A tech enthusiast with a love for languages, Bhattacharya knew this was his dream job. He had previously worked with for-profit organisations but had always left abruptly and unsatisfied—feeling they prioritised profit over impact. Adalat AI was different.

“As they say, you date before you marry. So I worked with Saxena for a while, and soon we became co-founders,” recalled Bhattacharya.

But it wasn’t that easy. When Saxena first told Bhattacharya about the stenography problem in courts, he didn’t take it seriously. However, once he visited the courts himself, his perception changed.

“I saw piles of papers and chits scattered all over the desks outside the courtrooms. A dedicated staff member was surfing through these pages, pulling out one file after another, going through them rigorously. I thought, what they’re doing could have been done with a simple Google search. That’s when it finally made sense to me what Utkarsh was saying,” Bhattacharya said.

The platform was initially designed to transcribe spoken English to text. It gradually expanded to support other languages commonly used in Indian courts. And with errors and trials, the linguistic transcription was finally achieved.

For stenographers, Adalat AI came with apprehension. Many feared losing their jobs. A few even tried convincing judges not to use the platform, arguing that AI couldn’t compete with human skill. But as soon as they saw how the AI worked, they couldn’t resist the comfort.

“Now, we’re able to focus on other tasks—like uploading on the live court system and handling documentation,” said a stenographer working with a senior judge in Andhra Pradesh.

Then, with a nervous laugh, he added, “But you do know, even that work will be taken over by AI. I guess they’ll shift us to some other department.”

Just a few metres away, another stenographer chuckled and said, “I’m safe. My judge doesn’t use AI yet. He doesn’t even know how to use his smartphone properly.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)