Gurugram: Stationed at the Tughlaq Road roundabout, Delhi Police ASI Man Singh Patel oversees the security route during Parliament’s winter session. It is the same post where he was on duty 24 years ago on 13 December 2001, when a colleague sped up to him on a motorbike with shattering news. His father, head constable Ghanshyam Patel, had been shot dead on duty.

The building, standing tall before him every day, never lets him forget where it happened. And new terror attacks such as the Red Fort blast on 10 November force him to relive the visceral grief.

“I still remember that day and time, 1 pm. Look at me, I am still standing here. To the world, I may seem the same, but I know how my world changed after my father left me,” said Patel.

He was 34 when his father died as part of the Vice President’s security detail in the attack perpetrated by five terrorists of Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM). Like other families of the victims, gallantry awards, tribute statues, government jobs, and petrol pumps haven’t been enough to fend off the haunting memories every time there’s a new attack.

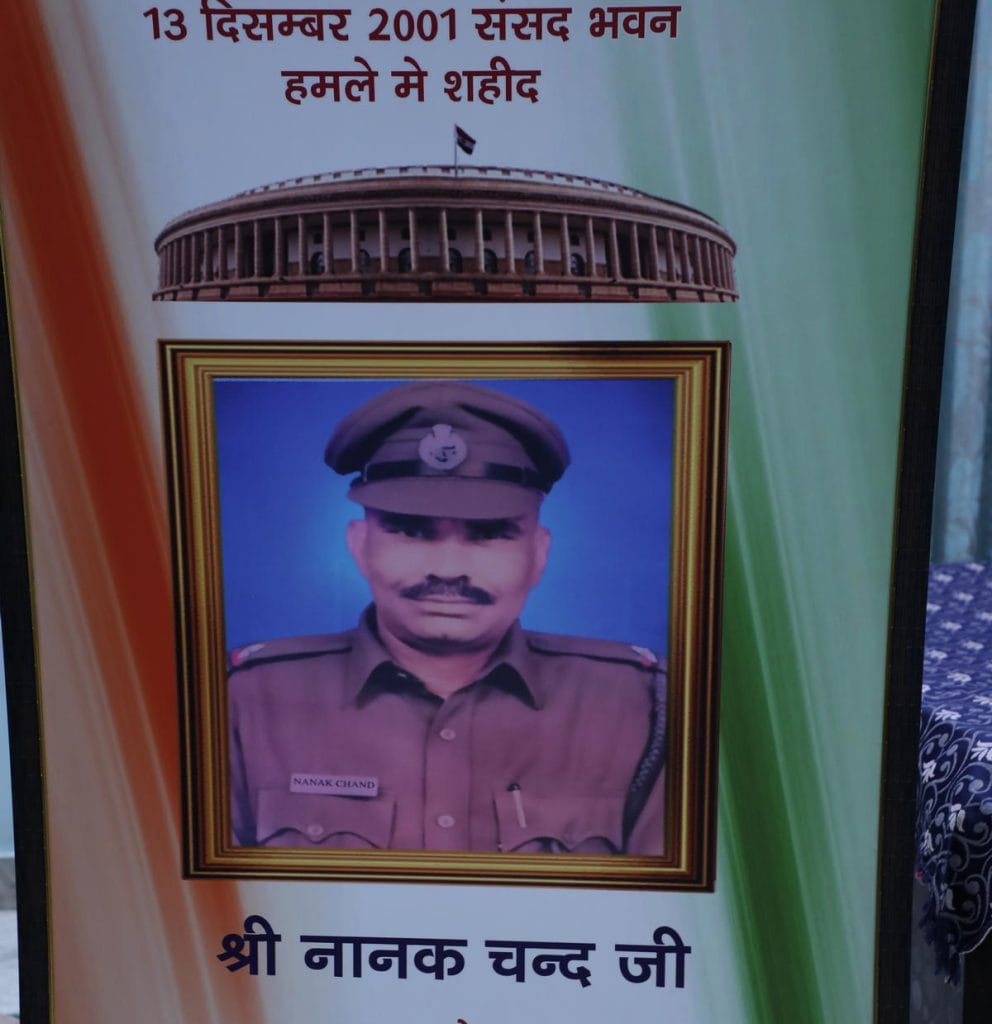

For Indrajit Chand, too, the Red Fort blast reopened the wound. It took him back to his 15-year-old self and to the day his father, ASI Nanak Chand, was killed at the age of 45. “Which child has lost their father today?” was one of his first thoughts, he said.

“I think of the children who lost their parents in that attack and the ordeal they’ll go through. I see myself in them. I relive my childhood in a blur,” Indrajit said, wiping his tears.

The 2001 attack could have been even more devastating had it not been for the bravery of the police and security personnel. The Pakistani terrorists broke through the security ring at Parliament complex but their attempt to storm the building was thwarted by personnel assigned to protect the vice president, as well as Parliament’s Watch and Ward staff.

Five policemen were killed: Ghanshyam Patel, Nanak Chand, head constable Rampal Singh, ASI Om Prakash, and constable Bijender Singh. The assailants also shot dead Rajya Sabha Secretariat security assistants Jagdish Prasad Yadav and Matbar Singh Negi, CRPF constable Kamlesh Kumari Yadav, and Deshraj, a gardener with the Central Public Works Department.

Then Union home minister, LK Advani, called it “the most audacious” and “most alarming” act of terrorism in the nearly two-decade-long history of Pakistan-sponsored terrorism in India. The probe traced the plot to JeM and identified Afzal Guru as the key coordinator in India. He was convicted and hanged in 2013, while others arrested during the investigation were later acquitted for lack of evidence.

Nearly a quarter of a century later, the families of those killed still visit Parliament every December to pay tribute to their loved ones. At the entrance to their villages, statues of the martyrs greet every visitor. But they would give up this glory in a heartbeat.

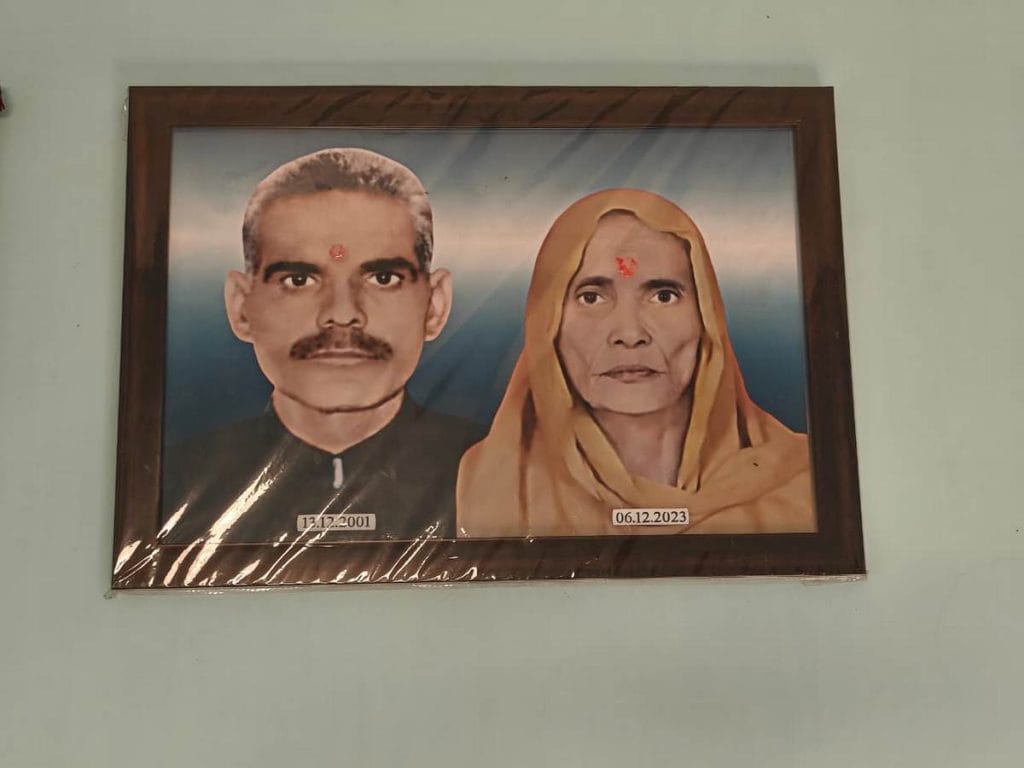

“My husband became a martyr, but I wish he was here with me—retired from the job, soaking in the December sun, watching our grandchildren grow,” said Ganga Devi, wife of Nanak Chand, at the Gurugram home she shares with her elder son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren.

Also Read: How a Hindu murderer on parole became ‘namazi Rahim’ and evaded arrest for 36 years

Solace in bravery

A collage of newspaper cuttings is neatly stacked in a file labelled ‘Martyr Bijender Singh’ in his wife Jaywati’s home in Delhi’s Badarpur. One shows the constable on the scene, his hand pressed to his chest where he’d been shot; he died hours later.

“He was telling his brother that he would be fine. It’s just a bullet in the chest. He was that brave,” said Jaywati, now 61.

One of the old clippings shows her wiping her eyes with a dupatta. The black hair in the picture has turned white and her skin is now lined with wrinkles.

When Bijender died, Jaywati was left alone with five children—two young sons and three daughters. Over the next 24 years, she dropped them at school, fed them, and constantly searched for a small corner in her house where she could cry in private.

Every time I felt low, I used to wonder how he must have felt when he was shot in the chest and yet continued to help others. Like a Bollywood hero in the movies

“I never really had time to grieve. Whenever I felt like crying or thinking about what my life had become, one of my children would appear in front of me. Raising them took up all my time,” she said.

To make ends meet, she relied on Bijender’s pension and a petrol pump allotted to the families of the victims. Her sons still run the pump, and another has taken his father’s job. But they grew up with almost no memory of him.

“I was just nine years old. I don’t remember much about him,” said Vipin, 33, looking at a portrait of his father on the opposite wall.

It’s still painful for Jaywati to recall the chain of events that led to Bijender’s death. He left his Army job in 1975 to stay with her and later joined the Delhi Police.

“He just couldn’t stay away from me,” she laughed.

The day of the attack he was not supposed to be on duty.

“He was on holiday when a friend called and asked him to cover his shift. He would do his next one later. It was his fate.”

In the Red Fort blast, it was a Hyundai i20 loaded with explosives. In 2001, it was a white Ambassador, complete with a VIP beacon, carrying armed terrorists. The car got past the first gate at Parliament, but the moment it struck the vice president’s parked cavalcade, the plan began to unravel. Security and police personnel acted quickly and the attackers were killed before they could enter the building. But not before they fatally wounded some of those who tried to stop them, including constable Bijender Singh.

Jaywati says she still finds some solace in thinking about how her husband fought back the terrorists and tried to save others.

“Every time I felt low, I used to wonder how he must have felt when he was shot in the chest and yet continued to help others. Like a Bollywood hero in the movies.”

Every year, the families meet at Parliament, checking in on each other’s lives—what has changed, what hasn’t.

“It feels like a community,” she said. “Someone who can understand us, because they have gone through the same.”

After the frantic years of raising children alone, her days are now calmer. She enjoys playing with her young grandchildren and their dog, Jo Jo.

“I can’t put my lonely journey into words. It was really difficult to do it all by myself. Five children? Can you imagine? He must have seen it all from above,” she said.

Petrol pumps and government jobs

A long portrait of ASI Om Prakash Dabas hangs in the small corner office of the petrol pump allotted by the government in Delhi’s Rohini area, a reminder to everyone who stops there why the place is known as the ‘martyr pump’.

“The family has been doing well, and we are not short on anything,” said his son Manoj Kumar, 47. “But can any petrol pump or job erase the trauma of five brothers who lost their father?”

The year 2001 dealt him two blows. Manoj lost his left hand in an accident and was still in hospital when his father died.

“I returned home from hospital on the day of rituals. My younger brother, who was very young at the time, suffered it all alone. My mother told me that he was not letting go of babuji’s hand before he was taken away for cremation,” Manoj recalled, tears welling up.

That younger brother, Deepak, is now an assistant sub-inspector with the Delhi Police. He was the first person Manoj called when the Red Fort news alert popped up on his phone.

“Our lives have been shaped in such a way,” he said.

The family has been doing well, and we are not short on anything. But can any petrol pump or job erase the trauma of five brothers who lost their father?

-Manoj Kumar, son of Om Prakash Dabas

For this family, policing was a generational vocation. Their grandfather, Chaudhary Sardar Singh, retired as a sub-inspector in 1992. All his sons followed him into the Delhi Police, and one joined the Army.

At the time of the attack, Om Prakash was about to leave VIP security and begin ASI training at the police academy in Jharoda Kalan.

“He had got a long overdue promotion as ASI. He was scheduled to go for training on 15 December but destiny had other plans,” Manoj Kumar added.

After Om Prakash’s death, their grandfather took charge of the household and toiled hard to get the petrol pump of the Indian Oil Corporation Limited operational. Deepak later joined the Delhi Police on compassionate grounds, and the extended family continues to live as a joint household.

For others, life after the attack took a different course, away from Delhi.

A father’s quest

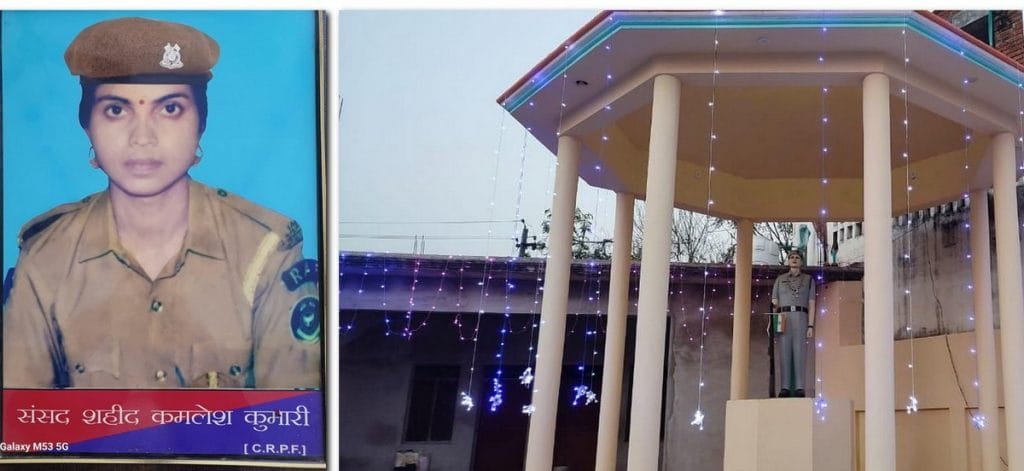

When his wife Kamlesh Kumari, a CRPF constable, was killed, Awdesh Kumar was left alone with two young daughters. The government offered him a job and a petrol pump, but he wanted a fresh start away from Delhi and moved to their hometown Kannauj.

“Delhi didn’t bring us any luck,” he said over the phone.

His first and foremost mission was to educate his daughters in a way that would have made Kamlesh proud.

Today, both daughters, Shweta and Jyoti, are doctors who completed their MBBS from government colleges.

“It has been a long and treacherous journey over two decades,” Awdesh recalled. “My in-laws stepped in to help raise the girls. They stayed with us for the first three to four years and supported us in rebuilding our lives.”

Kabhi kabhi majbuti jawab de jata hai (I lose my strength at times)

-Awdesh, husband of Kamlesh Kumari

Kamlesh was the only woman to die in the 2001 attack. She was the one who bravely followed the attackers starting at gate 11 where she was deployed and raised an alarm, alerting security forces and parliamentarians. Her warning ensured the doors were closed in time. She was posthumously awarded the Ashoka Chakra, the country’s highest peacetime gallantry award

शहीदों को श्रद्धांजलि!

दिल्ली में 13 दिसंबर, 2001 को संसद भवन पर हुए आतंकवादी हमले के दौरान असाधारण वीरता, असीम दृढ़ता एवं कर्तव्य परायणता का प्रदर्शन करते हुए हमले को नाकाम करने में महत्वपूर्ण भूमिका निभाने वाली 88 बटा. #सीआरपीएफ की शूरवीर CT(Mahila) कमलेश कुमारी ने मातृभूमि की… pic.twitter.com/5vpl1jNXfw

— 🇮🇳CRPF🇮🇳 (@crpfindia) December 13, 2024

Kamlesh and her family had moved to Delhi only six months earlier. Awdesh had just returned to their rented Uttam Nagar apartment after picking up their elder daughter from school when he got the news from a CRPF constable waiting outside.

“He told me that my wife got injured in the terrorist attack. I rushed to Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital with my daughter where she was declared dead,” said Awdesh, breaking down. “Kabhi kabhi majbuti jawab de jata hai (I lose my strength at times).”

Although his relatives urged him to remarry, he didn’t. Honouring his wife through his daughters is his priority.

“Their mother was an independent and confident woman. I wanted the same for my daughters, but a better life too,” he said.

The elder daughter, Jyoti Gautam, is now a doctor at Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in Farrukhabad, Uttar Pradesh. Shweta, who was 18 months old when Kamlesh was killed, has completed her MBBS and is preparing for the NEET PG exam.

“Had Kamlesh been alive, she would have been a proud mother seeing her two daughters becoming doctors,” Awdesh said.

The daughter of another victim JP Yadav, who was employed as a security assistant at the Parliament, also became a doctor and joined a government hospital in Jaipur as a medical officer. Her elder brother Gaurav Yadav is working in the Rajya Sabha.

“We feel proud. My mother takes pride in the fact that my father sacrificed his life on the biggest platform of our country,” said Gaurav Yadav.

Also Read: Malegaon & its many rewrites. Riots, bombs, Superman & now Reels

Living with 13 December

The past occupies an outsize space of those left behind. But for Man Singh Patel, every winter brings an unsettling sense of déjà vu.

“Twenty-four years have passed, but when duty is assigned during the winter session, everything comes back to memory,” he said at his post on the roundabout.

Little has changed since that day—except Delhi’s air, now more toxic, and its winters, warmer than what he remembers.

“However old you are, till your father is alive, you take life a little easier. That day, I grew older,” he said.

In her younger days, Ganga Devi saw the unfolding of the India-China war and the creation of Bangladesh, but it all seemed far removed until terror knocked on her door.

Her husband Nanak Chand’s death has made her an avid news hound. She watches TV debates, reads the newspaper every morning. She follows up on every terror attack, be it Pulwama or Red Fort.

“Ask me anything. I will tell you,” she said with authority. The letter from Parliament, inviting her to the annual memorial ceremony, rests neatly on the table. As always, she is going with her children and grandchildren.

“But will I forget him? Never. I will meet him there now and tell him everything—my life without him,” she said, looking up at the sky.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)