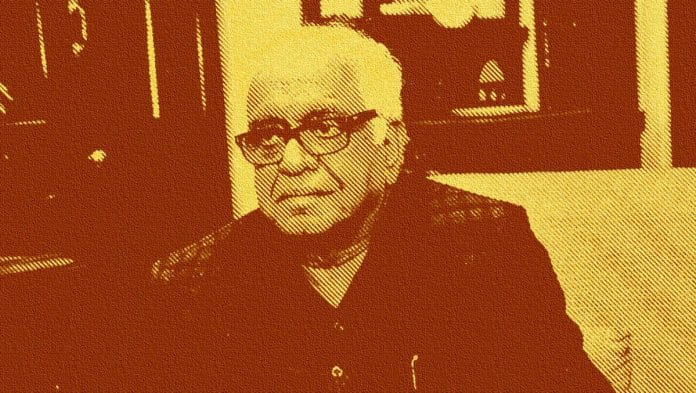

Mukul Mudgal has been accused by a family friend of forcing himself on her in the 1990s. Former judge vehemently denies it.

New Delhi: On a winter night in the early 1990s, Mukul Mudgal, who would go on to become chief justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, allegedly waited in the parking lot of a house in A Block in Delhi’s upscale Nizamuddin East for a woman he knew through her cousin.

She said she emerged some time later from a Maruti 800 — having just driven back from a friend’s house — and was politely asked for a cup of coffee by Mudgal. It was around 11 pm, an unusual hour to be asking for coffee, but choosing not to dwell upon it, she let Mudgal in.

“I wasn’t pleased about it, and that must have been some kind of basic instinct that I didn’t know how to read,” the woman, 59, told ThePrint, insisting that only Mudgal be named.

Mudgal and she had apparently been well-acquainted with one another since her cousin married a relative of his. She worked in a design firm and lived alone. But their relationship was certainly not one that warranted spontaneous visits late at night, she recalled.

“We weren’t ever taught that when a man asks to come into your home at 11 at night, and you don’t want him there, you say no.”

Like countless other Indian women, lines of consent were never discussed in her home growing up, let alone a sense of discomfort arising from situations like the one she found herself in that night. So, it was swept aside, and feeling the weight of familial obligation, she said she proceeded up the stairs with him in tow.

She opened the door to the small barsati of the house, and made two cups of coffee. But before she could finish, she alleged he grabbed the cup from her, put it down on a surface nearby, and slammed her onto the bed in the room.

“I was down on the bed, and he was on top of me with full force. And I mean full force,” she alleged, grimacing.

As she narrated what she said happened that night, her body recoiled, and she pulled a hand over her face. “He slobbered all over me…It was disgusting.”

Before that night, she said she never would have imagined that Mukul Mudgal, a man with whom she had shared strictly familial relations, would come into her home on the pretence of wanting coffee and assault her.

“You know, when you’re pressed down by a man who is stronger than you and you’re trying to push him off with everything you’ve got, all you can manage is a grunt. You can’t even scream.”

With her arms flailing and legs kicking, he finally relented and left the house, she said.

“He didn’t go all the way. He didn’t rape me. But he did attack me.”

Reached for comment, Mudgal, 69, denied the allegation as “utterly false and baseless”.

“The alleged incident is said to have taken place more than 25 years ago. While I did have a few meals with her around that period, our friendship did not continue as I felt that we did not have much in common,” Mudgal told ThePrint.

“However, the allegations that I went to her house or that I had assaulted her and caused bruises are utterly false and baseless.

“I have lived a life without moral blemish. I have worked and moved with women of different ages and different spheres of life without giving a cause for complaint to anyone,” he said.

Also read: India’s #MeToo accused are back in action – with wedding bells & celebratory cake

‘I was covered in bruises’

By 1990, Mudgal was a lawyer well on his way to eminence. He was already an Advocate on Record in the Supreme Court and a member secretary/treasurer of the Supreme Court’s Legal Aid Committee, positions he kept until 1998 and 1995 respectively.

In 1989, he rose to prominence working alongside one of India’s most powerful jurists and attorney generals, Soli J. Sorabjee, representing six cricketers who had been banned by the BCCI. It was a case that shook the world of cricket, and Sorabjee and Mudgal emerged from the case as heroes.

It didn’t occur to her, she alleged, that a man of such competence would turn up uninvited, blatantly disregard her palpable resistance, and continue to “violently” hold her down as she struggled to push him off.

“When I saw myself the next day, I was covered in bruises. Even the exposed parts of my neck and shoulders were totally black and blue,” she said.

A friend of the woman from the time told ThePrint that she knew about the alleged assault and saw the bruises on her body.

“She had come to my house, and she told me that Mr Mudgal had tried to force himself upon her. She showed me the bruises. They were over her neck and shoulders,” the friend told ThePrint.

“I felt so ashamed, I remember thinking I had to cover the bruises that were exposed, and I wrapped myself up in a shawl,” said the woman.

But unavoidable circumstances led to uncomfortable run-ins with Mudgal, she claimed.

“When I met him at my cousin’s house soon after, I ignored him and tried to go about my day. But I must have been acting strangely, because when we had a moment alone, my cousin asked me ‘Why are you behaving so badly?’ So, I unwrapped the shawl and showed him what Mudgal did.”

Her cousin stayed quiet and did nothing about the allegation at the time: Mudgal was apparently an indispensable part of their closely-knit group of friends and family. Until then, Mudgal’s visits to her cousin’s house with tea-time snacks had become an evening ritual.

Mudgal came from a family rich in taste of food, music and culture, having produced some of India’s finest artists who now head Delhi’s Gandharva Mahavidyalaya. She was well-acquainted with his family, and sharing meals with them was a regular occurrence.

Before the alleged attack, she said she and Mudgal had only spent one other occasion alone, eating out at Yashwant Place in the diplomatic neighbourhood of Chanakyapuri. She recalled nothing having gone amiss.

“I had no reason to feel threatened by him. The time we spent together wasn’t suggestive or romantic in any way. It was just two people sharing some food.”

A few days after the alleged assault, she said Mudgal came knocking on her door for forgiveness.

“He said he was sorry for what had happened, but that he was sad and lonely because his wife had just left him,” she claimed.

“He didn’t say he had committed a violent crime. No. He said he was upset because his wife was gone, and that was his explanation.”

She showed him her bruises and turned him away, she said.

The trajectory of Mudgal’s career, meanwhile, was on a steady incline: He continued to take up cases in civil law, constitutional law and labour law, and working on prison reforms.

In 1998, Mudgal was elevated to the position of judge in the Delhi High Court.

Also read: #MeToo clean chit to BCCI’s Rahul Johri: Divided CoA can’t serve Indian cricket well

Why she’s speaking up now

During his tenure as a judge, Mudgal was said to have been liberal-minded and sensitive in his judgments. In Gaurav Sondhi vs Diya Sondhi, a well-known case adjudicated by him, he ruled that after divorce, women should be given maintenance within the first 10 days of the month.

It was among judgments seen as progressive and in favour of gender equality. In 2009, Mudgal was made chief justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court.

As he grew in stature as a judge, he and the woman he allegedly assaulted crossed paths on and off, even after she moved out of Nizamuddin East and went on to marry. At social gatherings and other occasions, she was unfailingly subject to obsequious greetings from him, she said. He would approach her almost fearfully, so as to placate her hostility, she claimed.

“For years I couldn’t say anything because of how close our families were. I felt too many people would be hurt if I spoke up against him,” the woman said.

It took years, she said, to understand the gravity and effect of their collective silence — her’s, her cousin’s and Mudgal’s — on her sense of justice.

At the time of the alleged assault, and the years after it, she considered the shame of the incident to be solely hers, she said. But that changed in 2016, when a next-door neighbour allegedly sexually harassed and impersonated her daughter online. An FIR was filed but the only action taken by the police, the woman claimed, was that the neighbour was questioned.

Her daughter’s experience, compounded by her own, has shaken her faith in the judiciary and courts to an irreconcilable degree, she said.

“Everything magnified for me when my daughter was targeted,” she said, adding that one thought kept bothering her: “If you are representing the judiciary and are a perpetrator yourself, what right do you have to take that chair?”

Two months back, the #MeToo campaign that was making headlines encouraged her to confront Mudgal, she said. She sent him a message on WhatsApp on 18 October, she said. He apparently asked if he could call her, she said no. Mudgal’s next move was to get in touch with her cousin.

The cousin later called the woman and said Mudgal had made a “mistake”, she claimed.

Infuriated and upset that Mudgal’s action could be viewed as a “mistake”, she said she decided to come out with her story.

“All these years later, what Mudgal did is still considered a mistake,” she told ThePrint. “He continues to justify his actions by saying he was sad and lonely.”

It was no mistake, she said. “It was a crime. With intent.”

But, according to Mudgal, he “didn’t understand what had upset her”.

“I spoke to her cousin to find out what was troubling her,” Mudgal told ThePrint in an email.

“I told him that I was willing to say sorry about anything which had hurt her feelings.”

When asked to comment on the cousin using the word “mistake”, Mudgal denied using the word.

“I did not say to him that I had made a mistake. However, it is possible her cousin may have used those words or even added something else in order to resolve the matter.”

ThePrint is privy to the text messages exchanged between the woman and Mudgal, as well as the telephone calls between her and her cousin.

Mudgal no longer adjudicates, having retired as chief justice in 2011. He headed the Mudgal Committee, formed by the Supreme Court in 2013 to conduct independent inquiries into allegations of corruption in the Indian cricket board.

He is also a member of the FIFA Governance Committee and Review Committee, and he continues to be invited for panel discussions for events and news debates.

But for the woman, telling her story is neither about exacting revenge nor about getting even for an injustice done to her decades ago, she said.

“I want to tell this story because my child has suffered the same fate — even if in a different way,” she said. “If the keepers of the law are themselves the perpetrators, can any woman hope to have any justice?”

Also read: Smita Patil’s Mirch Masala is the movie a post-#MeToo India must watch