In India, every time a woman swipes right on a dating app, the excitement and hope is tinged with fear. That fear is now exacerbated in the wake of Shraddha Walker’s murder. Her live-in partner Aftab Amin Poonawalla, whom she met on Bumble, has been arrested for murder and, according to the police, chopping her body into 35 pieces which they claim he stored in the fridge at their Mehrauli house.

But what has made app dating suddenly scarier is the police claim that Aftab invited a woman to his house on a date while Shraddha’s body parts lay in the refrigerator. This puts in focus the mechanisms available to women for reporting their dating partners and their experiences with them.

The horror stories

When dating apps first burst into the scene—starting with Tinder in 2012—they promised to demystify and democratise the dating game. But today, people are treading these digital playgrounds carefully.

In a 2019 report by ProPublica and Columbia Journalism Investigations released in the United States, “more than a third of the 1,200 women surveyed said they had been sexually assaulted by someone they had met through a dating app. “Of these women, more than half said they were raped.”

Many women on Hinge, Tinder, Bumble, and Aisle spoke to ThePrint about their experiences of harassment, stalking, assault, and even rape.

“I was seeing an ad maker for about three months in 2019, and it fizzled out by July. I forgot all about him and started dating someone else,” recalls the Mumbai-based filmmaker. “During Christmas, the man showed up at my doorstep and insisted on coming upstairs. It was 11:30 in the night and I requested him to leave soon, but he started drinking alcohol,” she said, adding that he “kept yelling” about how he had told his mother about them.

A Kolkata-based professional recalls meeting a womaniser on Aisle and reporting him to the company authorities. “This happened in 2018, and Aisle was fairly new. A representative named Sneha was in touch with me and asked me to share my ‘love story’ with them. I approached the same representative with information about the man. But no action was taken against him. He was an army officer,” she claims.

That said, not all complaints go unheard.

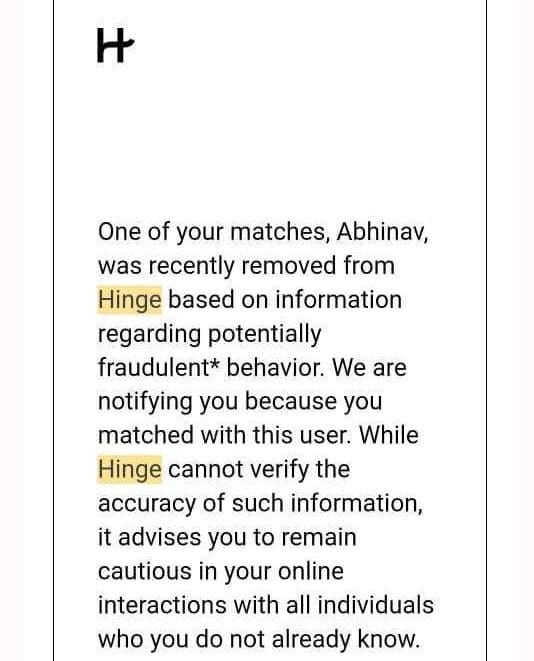

“I was raped by a man I met on Hinge. I had written an application, and, to my surprise, they instantly responded to me. Told me they had blocked the profile and offered legal assistance. That was a very reassuring experience,” a writer in New Delhi said. Hinge responded to the rape complaint within minutes on 6 June 2022, according to screenshots of the email seen by ThePrint. “If you report this incident to law enforcement, we will be glad to assist with any investigation,” a spokesperson of Hinge, who signed his name as Alfonso, wrote.

But there’s nothing stopping perpetrators from moving on to the next dating platform. ThePrint reached out to Tinder, Hinge, and Bumble to find out how many incidents of sexual assault and offence have been reported in 2022 and what action, if any, they took.

Tinder claims it has a “dedicated team” to deal with such reports and “works closely with the law enforcement”. Bumble too says that it was “devastated” to hear about Walker’s death and listed the mechanisms it has in place for the safety of its users. But neither Tinder nor Bumble shared data on the number of complaints they have received this year or the accounts they have blacklisted. Hinge is yet to respond.

Delhi Police has registered 284 cases of financial fraud committed via dating apps and has registered 5 cases of rape/assault/attempt to rape since 2020.

Also read: Indians transfixed on gory details of Shraddha Walker murder case are losing sight of facts

Safety and security on apps

Dating apps didn’t give birth to online love. People have been chasing their ‘Bollywood’ love stories ever since they could instantly message each other on the internet. But what online dating platforms have introduced is the possibility to take conversations offline and meet for dates.

This makes women, non-binary people, and homosexuals vulnerable to abuse. And often, the apps don’t play an active role in ensuring safety once you’re out of the chatbox, even though major dating sites have elaborately laid out security features for users.

Bumble markets itself as a feminist app where the power to initiate the conversation lies in the hands of the woman. It verifies photos to confirm user profiles and gives a ‘blue tick’ to verified ones. The app has banned photos of guns and weapons in profile pictures and has a private detector feature that automatically blurs lewd images.

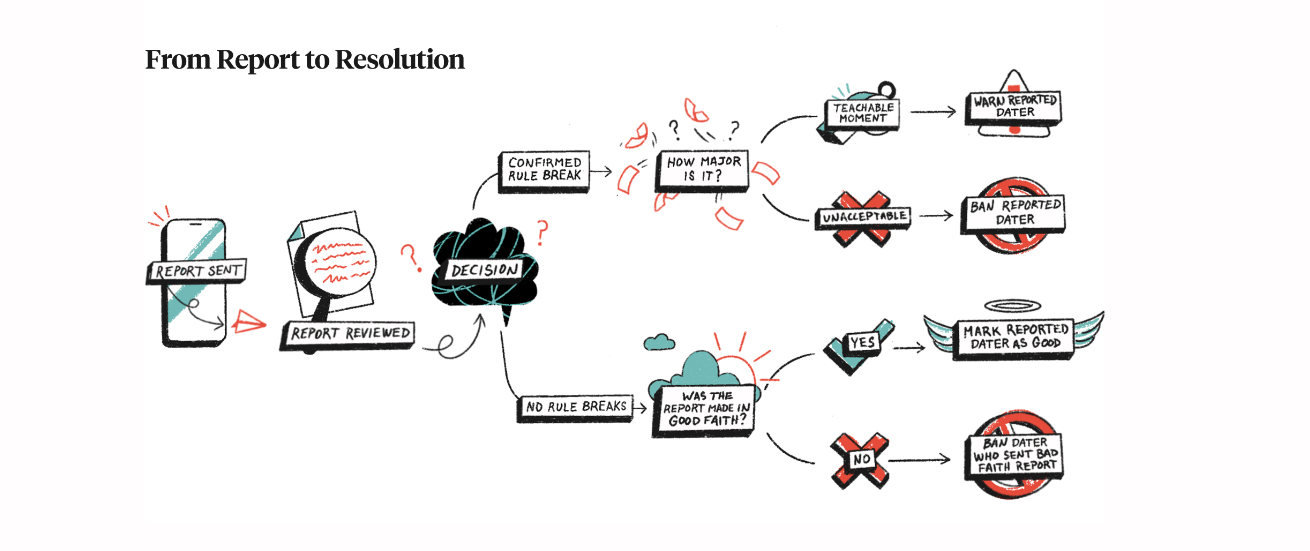

Hinge promises swift action on a report. “The moment someone is reported, we make sure you never see each other’s profile again. Reporting is anonymous to protect your safety,” says its safety guidelines.

The app has also taken active efforts to provide information to its members if the match has been found fraudulent.

Niche apps such as Truly Madly, with 11 million registered users in India, give the option of verifying profiles using government IDs. “Everyone has to provide photo verification, but if the user provides a government ID, their profile is considered more trustworthy and is more visible to other users,” said Snehil Khanor, founder and CEO of the dating app.

Khanor added that making a profile on the platform isn’t easy and that the app has an acceptance rate of just 42 per cent as a result of strenuous filtering mechanisms, which reduces the chances of impersonation.

Sometimes, resolution processes can be perceived as opaque, and emails by dating sites often land in the spam folder. To make the process more transparent, Tinder has introduced a progress bar for reports in the app where users can track resolution. The new feature gives users more confidence in coming out with experiences.

Match Group, Tinder’s parent company, also claims to have invested $125 million to make online dating a safer experience and employs 450 people who are exclusively focussed on building Tinder’s trust and safety portfolio.

Also read: Many Indian men are okay with their partners’ sexual history as long as they don’t know details

Not the first time

Despite all the safety features in place, online dating can turn horribly wrong very quickly — even for men. In 2018, Priya Seth was accused of murdering Dushyant Sharma, a man masquerading as a millionaire on Tinder. But such cases are far and few. More often than not, it’s the vulnerable groups who end up as victims.

Sextortion, too, has become all too common on dating apps—one of the emerging cons used by cyber thieves sitting in Jharkhand’s Jamtara and Haryana’s Mewat.

India has 31 million dating app users. A report by Brigham Young University in the US found that “violent sexual predators are using such apps to target women with vulnerabilities such as mental illnesses”.

The recent Netflix docuseries Tinder Swindler also highlighted the perils of meeting the perfect Prince Charming on the app — in reality, he might be a frog after your money. Stories of India’s own version of swindlers are also a cause for alarm. Members of the LGBTQIA+ community have been subjected to targeted abuse through dating apps such as Grindr.

Walker’s murder has just reenergised all these fears users have about dating apps. “I am reckless sometimes and invite people over to my house even on the first or second date because going out is so expensive,” said a 25-year-old ad professional who didn’t wish to be named. “Now, I’d rather have a decade-long dry spell than hop on Hinge, Bumble or any other dating app again,” she said.

With inputs from Bismee Taskin.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)