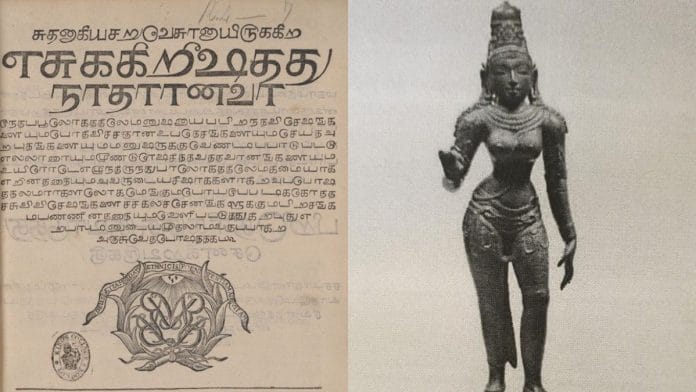

Inspector Indira cried when she saw the image of the 300-year-old Bible. It was the first Tamil translation of the holy book that had gone missing from Thanjavur’s Saraswathi Mahal Library Museum over 17 years ago.

“Everyone had written it off,” she said. “They said it was long gone, no way to retrieve it.” Others told her not to touch the case of the missing Bible since technically “it was not an idol”.

But Inspector Indira didn’t give up. “It is still an antique,” she had said back then. Though it disappeared nearly two decades ago, Indira was assigned the case only last year.

It was a hard case and took a year to crack. Her team circled the Saraswathi Mahal Museum for six months, left no angle, no space, no person uncovered, examined nearly 45 witnesses, and combed through dozens of art brochures of international museums and auction houses. The Bible was finally traced to King’s College, London. On the website, the title page looked frayed, but still well-preserved for its age.

Inspector Indira is part of a team of officials that make up the Tamil Nadu Idol Wing CID, an ongoing and ambitious drive to investigate the well-oiled, multi-million-dollar global smuggling racket of antiquities thefts from India. Tamil Nadu is the only state with an active Idol Wing set up in 1983. Others, including Kerala and Karnataka, showed interest in having one of their own. Since 2012, it has recovered more than 1,463 artefacts including 878 stolen idols.

Stolen antiquities from Tamil Nadu have been routinely funnelled into dodgy networks ending up in upmarket galleries and museums in the West. The most famous and recent suspect, Subhash Kapoor, is currently in Trichy Central Jail after being charged by Manhattan prosecutors for dealing in rare stolen artefacts with American museums.

In recent months, the Idol Wing has been in the news for recovering numerous idols from international auction houses and local art smugglers. In the last year alone, officials say they have brought back 10 idols: Six from the US, and four from Australia.

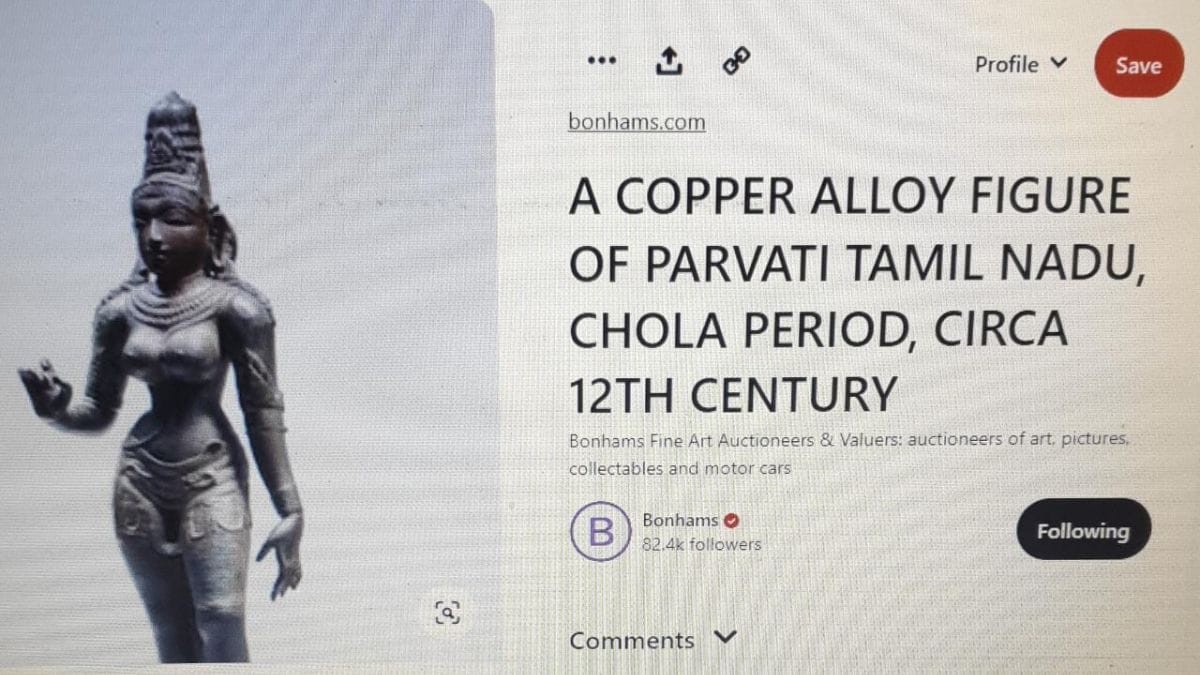

A Chola-period Parvati idol, stolen over 51 years ago, was traced to an auction house in London. A 19th-century painting of Tanjore Maharaja Serfoji II was found in a museum in the US. Inspector Indira is at the heart of all this activity. She heads the Kumbakonam unit under the state’s central zone, which is densely packed with temples commissioned by ancient Tamil kings and serves as a fertile ground for smugglers.

Also Read: ‘Indians never invaded’ is a myth. Guptas, Cholas, Lalitaditya Muktapida were conquerors

Search for the Bible

The Bible case was lying in a file that could have had an invisible mark on it saying, ‘difficult case’. This pushed Indira even more. In 2017, the Idol Wing dusted off the cobwebs and filed an FIR based on a complaint by activist Elephant Rajendran. But it was only recently under the new DGP K. Jayanth Murali—and Inspector Indira leading the team—that they started making headway in the case.

Word on the street was that in 2005 or even earlier, people from abroad, perhaps Germans or Danes, visited the Saraswathi Mahal museum after which the Bible went missing. “We had a lead,” Indira said.

Indira and her team travelled to Tharangambadi, or the Danish trading port of Tranquebar, where the original translation of the New Testament into Tamil was done by the Danish Christian Missionary Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg in 1715. “It was at his house that we found a photocopy of the Bible with Thanjavur Raja Serfoji’s signature. A copy made in Denmark,” she said.

The team started scouring the internet pouring over museum catalogues in Europe. “We started searching in Denmark’s surroundings….and landed up at King’s College, London.”

When the signatures matched with the photocopy, tears flowed, she said. “The museum staff were elated since they had been facing a lot of issues, such as stalled promotions and disciplinary actions since the Bible went missing,” she added.

When the Bible was traced, Saraswathi Mahal Museum staffers were ecstatic. They called Indira up to tell her they would throw her a party.

Also Read: Why is a dragon carved on Jain temple in Mangalore? Medieval Africa-China trade holds answer

Tracing down idols through old FIRs

At the Idol Wing’s Chennai headquarters, DGP K. Jayanth Murali said that ever since he took over in September 2021, the squad has been pulling out old FIRs that have been gathering dust for years. “We pulled out all such FIRs, deciding to take action on them.”

There was a time when the Idol Wing had been bogged down by court cases, he said. Now, the Wing solves a case a week, sometimes up to three.

Murali said there is a need for more sensitisation amongst all agencies to stop idol thefts. He describes the modus operandi for Chola bronzes, which involves the age-old trick of hiding in plain sight. The smuggler will buy nine fake idols from emporiums but makes one mould for the antique he is attempting to smuggle. He gets a certificate of export for the whole batch, and at the last minute, he removes the mould and replaces it with the original. “The Customs will pass it since there is a certificate,” said Murali, underscoring the need for experts to examine artefacts before they are shipped out of India.

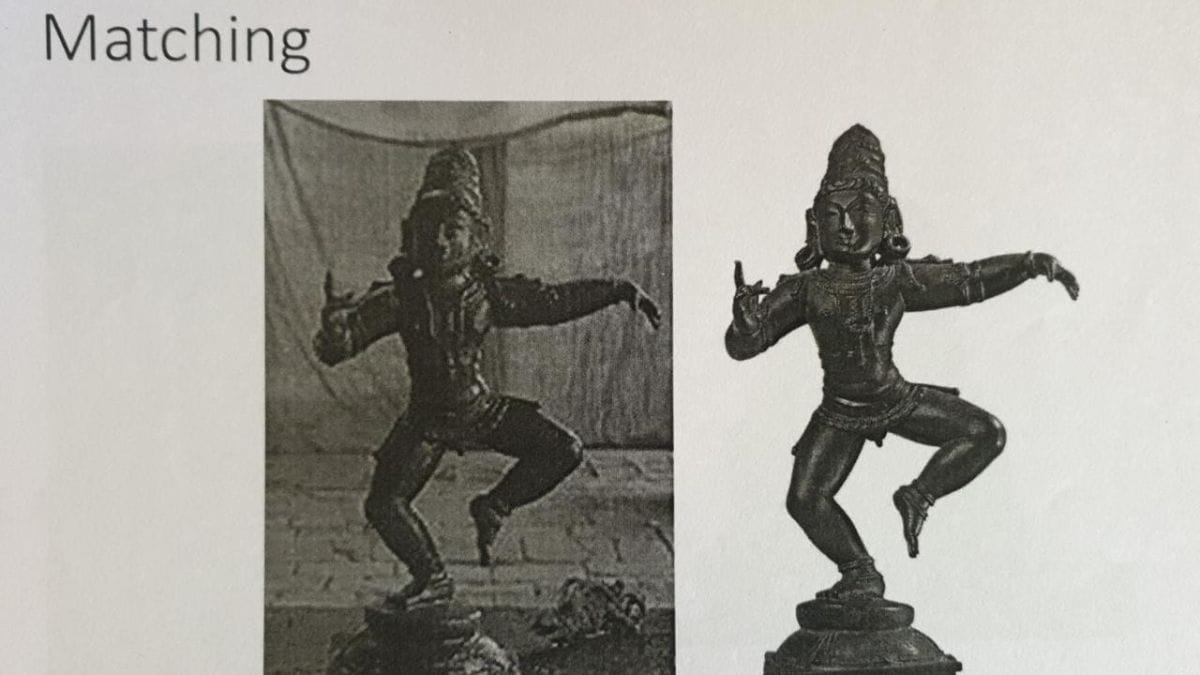

In the case of the Parvati Idol, the temple and the complainant did not have a photograph of the idol, Murali said. That is where the French Institute in Puducherry played a role. In 1959, they had taken a photograph of the Parvati Idol indicating the name of the temple. The team took that picture and started systematically going over museum catalogues online: Smithsonian, Asian Museum of Art, Victoria & Albert.

When they failed to make any headway with the museums, they turned to auction houses. “Lo and behold, we found it listed in Bonhams in London,” he said. The team sent the image from the auction company and the image from the French Institute to an expert who said it was a match. “We did this in a short span of the last one month,” said Murali. He opens his iPad to show ThePrint the idol at Bonhams, the image from the French Institute and the expert’s certificate on 3 August 2022.

But bringing an idol back to India involves a mountain of paperwork in accordance with a complex Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) and several missives sent across to different domestic and international government agencies. Once back, they are handed over to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which deals with antiques.

“Normally they [ASI] inform us, we go fetch the idol, it is remanded back to the court, the court gives the idol back and we give it to the temple,” said Murali.

Of the idols ‘retrieved’ in the past year, two cases are still in court, but eight idols have been handed over to the respective temples. The temple authority also conducts ceremonies before accepting the idol.

Murali said that at times it is not possible to trace the exact temple from which the idol was stolen. In such cases, the idol goes into an ‘icon centre’ – a temperature-controlled space in Kumbakonam where it joins other lost idols. The keys are with the district magistrate.

Also Read: Chola period wasn’t golden age of Tamils. Modern obsession with their glory is misplaced

The Antiquities Act of India

Vijay Kumar and his team at the India Pride Project, a team of volunteers who banded together in 2006 to trace stolen artefacts and works closely with the Idol Wing, said that Chola Bronzes are considered the highest watermark of Indian art.

This systematic looting of priceless artefacts can be traced to the colonial era, with not just the British, but the French, and Dutch shipping pieces of India’s history to Europe. “These are colonial loot but we also came to a phase in the 1920s, when because of what was being taken back during the colonial loot, Indian art was getting visibility abroad,” said Kumar.

Today, in India, he says the situation is dire. No central agency is tasked with bringing back idols. For a few years now, Kumar has been writing opinion articles calling out the “collecting lobby cabal’s” attempts to dilute the Antiquities Act of 1972.

Originally, the Antiquities Act, 1972, required registration of any artefact that is 100 or more years old. Once registered, it becomes unexportable but remains available to trade within India. After an artefact is registered, the registering officer from the ASI is supposed to conduct an enquiry – the how and where are recorded. But if the government recognises it to be of national importance, it can acquire the artefact at the market rate.

In 2019, amendments were proposed to the 1972 Act. The draft bill allows anyone to import an antiquity by uploading details of it on a web portal. Further, it proposes setting up of a domestic trade network and doing away with any licence which is now required for sale of antiquities.

In a 2019 article, Kumar argued that this would make India a source country as well as a destination for smuggled art. Unlike other source countries like Egypt or Italy, India does not have dedicated law enforcement agencies that can deal with art theft, he wrote.

“The ASI considers itself only a custodian and not an enforcer of the act. The only dedicated agency in the country is the idol wing in Tamil Nadu, which is treated as a punishment posting and is chronically understaffed,” Kumar wrote in a 2019 piece. “In several cases an FIR is not registered, let alone action taken.”

“Though this new amendment has been cleared, it has not come up for discussion in Parliament. Even if the government opens it for a short window, it will be a free for all,” he told ThePrint.

Also Read:

‘God’s work’

Vijay Kumar is a firm believer in the power of proper documentation and incentivising finders to hand over artefacts. It will curb theft of artefacts, he said.

For Indira, however, “a kind approach” goes a long way. “People genuinely don’t know who should hold on to artefacts and who shouldn’t, it is up to us to explain it to them in a kind manner,” she said.

In her last posting in Trichy, she had to maintain law and order in one of Tamil Nadu’s busiest tier-2 cities. A job that required a different set of skills. Now, it is a kinder approach to explaining to people why their heritage is important and how they can personally contribute to preserving it.

Last week, the Idol Wing traced two antique idols of Hindu deities Devi and Ganesha to museums in the US stolen 40 years ago from a temple in Nagapattinam. As work continues—physical raids in Tamil Nadu, scouring the internet on weak networks—the quest for artefacts continues with plans to bring back more Chola Bronzes and Buddha idols.

“In the Idol Wing nobody behaves like cops in the movie,” Indira laughed. It is about creating awareness. “After all we are doing God’s work.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)