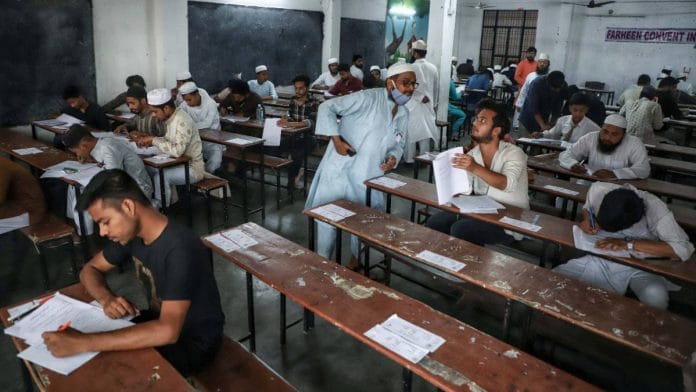

New Delhi: The Supreme Court’s ruling on madrasa education in Uttar Pradesh has split two siblings in Hapur. For 18-year-old Mohammad Yasir, a maulvi student at Madrasa Iqra Public School, it’s come as a relief—his 10th and 12th-grade studies are now considered valid. But for his older brother Siddiq, who is pursuing a college-level Kamil degree in the same madrasa, it’s a bitter setback.

This week, the Supreme Court upheld most of the Uttar Pradesh Madrasa Education Act 2004, but declared that higher Kamil and Fazil degrees are non-compliant with University Grants Commission standards. Now, Siddiq is considering dropping out, worried his degree won’t be recognised.

Eight months after Allahabad High Court ruled that the Madrasa Act was unconstitutional, the Supreme Court overturned it. While it brought relief, there is now a new challenge. Young job-hunting Muslims with undergraduate and graduate-level degrees from madrasas are now left in confusion and despair.

“When the court has said that this degree holds no value, there’s no point in continuing my studies,” said Siddiq, a second-year Kamil student who is studying Urdu with the hopes of becoming a teacher. “I’ve already wasted a year on this, but I won’t waste more. “Why should I pay fees for a course that has no value?”

The Supreme Court’s decision has left over 35,000 students in Kamil and Fazil programmes at madrasas across Uttar Pradesh anxious about their future. Teachers and madrasa organisations warn it could drive up dropout rates, further destabilising education in these beleaguered institutions. They’re now urging the Uttar Pradesh government to recognise these programmes and reform course structures, while the UP Madarsa Board awaits an official response from the state.

Political reactions to the verdict have been mixed, with BJP leaders calling it an impetus for reform and their Congress and Samajwadi Party counterparts questioning the effects on minority rights.

According to the UP Madarsa Board, this year, a total of 114,723 madrasa students in the state appeared for the Maulvi, Munshi, Kamil, Alim, and Fazil exams in May. In the madrasa system, Munshi/Maulvi programmes equate to secondary education, Alim to senior secondary, Kamil to graduation, and Fazil to post-graduation. These higher degrees include various specialisations, including Arabic literature, Islamic jurisprudence, and comparative religion.

UP Madarsa Board chairman Dr Iftikhar Ahmed Javed told ThePrint that over 26,000 students are enrolled in the Kamil programme and more than 9,000 in Fazil courses.

“Those who have already passed out from these programmes will not be affected, but those currently enrolled will be impacted,” Javed said.

The ruling has also unsettled madrasa teachers.

“This will have a deep impact on the students. Many are still unaware of it, but a sense of unease has spread among madrasa teachers. The government should take action on this soon,” said Mehtab Alam, a teacher at Madrasa Iqra Public School.

Also Read: Right to run madrasa not ‘right to maladminister’. What SC said while upholding UP law

‘Hard work has gone to waste’

For 24-year-old Siddiq, a higher madrasa degree was his last shot at a stable job. He’d once dreamed of getting into medicine, but claimed “circumstances” forced him to take the arts as his stream. Confident in his Urdu skills, he then set his sights on a madrasa degree and teaching—until the court’s decision tore that plan apart.

“All my hard work has gone to waste. This is like taking away my right to education. I will have to look for other options now,” he said.

Still, Siddiq advocates for the idea that madrasas should offer modern education alongside religious studies. But he also argues that government universities should include Islamic studies.

“Many in the Muslim community value religious education, which is why they send their children to madrasas. The government should introduce programmes related to Islam or religious education in universities to increase Muslim enrollment,” he said.

A push for reform?

The ruling has stirred up different reactions within the Muslim community, with some viewing it as a long-overdue push to bring madrasa education into the 21st century.

“We need to improve the level of the Kamil and Fazil programmes,” said Azeemullah Faridi, chairman of the Modern Madrasa Teacher Association. According to him, Kamil and Fazil degrees cannot be considered equivalent to graduation and post-graduation qualifications as they heavily lean on religious studies rather than modern subjects like science, math, and social science.

He added that although these degrees weren’t recognised even before the ruling, the verdict opens the door for much-needed reforms.

In contrast, traditional madrasa organisations are calling for the Yogi government to step in and validate these programmes immediately. They also demand a separate university specifically for madrasas.

In August, UP Minority Welfare Minister Om Prakash Rajbhar announced plans for two universities to affiliate all state madrasas. Other possible options are in play too.

According to Israr Ahmed, joint secretary of the Madarsa Adhunikikaran Shikshak Ekta Samiti, if the government cannot establish these universities, it could affiliate the Kamil and Fazil programmes with Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti Language University, which would make it easier to grant validity to these courses.

“The government should affiliate these programmes soon or shut them down, which is not possible as many students are already enrolled,” Ahmed said.

He added that various organisations associated with madrasas are deliberating on the court’s decision and will soon meet with the state minority affairs minister to discuss the issue, as well as the “effective implementation” of the central government’s Scheme for Providing Quality Education in Madrasas (SPQEM).

Political reactions have also been polarised. Congress leader Rashid Alvi criticised the verdict, arguing that the Constitution grants minorities the right to establish and manage madrasas as they see fit. “If some court or government gives such a verdict, it is unfortunate,” he said. BJP leader Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi, however, described the ruling as an opportunity for “reform”, emphasising the importance of integrating madrasas with formal education to improve students’ job prospects. While Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav refrained from commenting on the details of the ruling, took aim at the UP government, accusing it of repeated constitutional violations.

All in all, though, Muslim organisations have largely welcomed the Supreme Court’s verdict, viewing it as a long-awaited win for the legitimacy of school-level madrasa education.

“This decision is like a slap in the face for those who were trying to abolish the Madarsa Act,” said UP Madarsa Board chairman Javed.

The net result, according to him, will be positive, as the verdict will counter negative campaigns against madrasas, reduce dropout rates, and improve their public image.

The other side of the coin is those who think that madrasas impinge on the constitutional rights of their students.

Reacting sharply to the verdict, Priyank Kanoongo, chairperson of the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR), said that it was “disheartening” that the Supreme Court had stayed silent on this issue. He, however, praised the court for recognising its concern that Hindu students should not receive Islamic education in government-funded madrasas.

Also Read: Masjids, migrants, mobility. Himachal is becoming a new anti-mosque hotspot

Students in limbo

Despite his support for the ruling, Javed expressed concern for Kamil and Fazil students. For years, these degrees have held limited value outside madrasa circles, offering little advantage in admissions or employment. While the Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti Language University was established specifically to affiliate these programmes, no progress has been made on this.

Javed claimed he has written “dozens of letters” to push for official recognition of these programmes, but his requests have been left gathering dust in files.

“I wrote the last letter to the state’s education department last year, but have yet to receive any response. It is clear that these programs cannot continue in this manner,” he said.

Efforts to grant these programmes formal validity have been ongoing for years, he added, only to reach a standstill in the final stages. However, Javed is still optimistic that with the right attention from authorities, official recognition could be achieved swiftly.

“Many things have already been done,” Javed said, adding that he will soon meet officials to discuss the matter.

Meanwhile, Siddiq and his family are frantically reassessing their options. His younger brother Yasir had hoped that a Kamil or Fazil degree would pave the way to a career in unani medicine, but now they are thinking of switching to a different educational board.

“Now we will have to knock on the door of another board,” Siddiq said. “We won’t let our future be ruined like this.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)