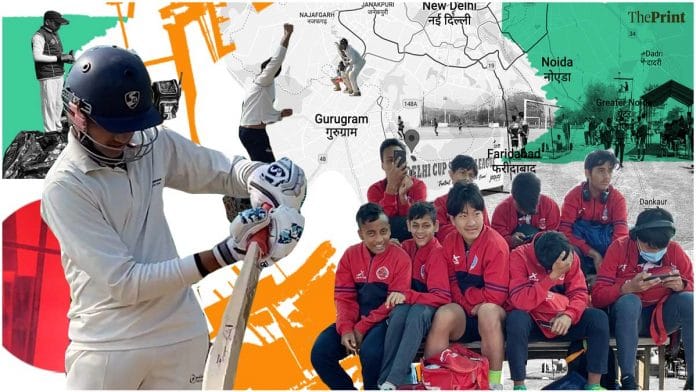

Sameer, 15, from Mewat travelled 40 km to reach the cricket coaching academy in Baliawas, near Gurugram, where he was practising for a trial with about two dozen boys his age. When we meet him on a Sunday morning at 11, Sameer had been bowling at the nets for three hours, working towards fulfilling his and his farmer father’s dream — of playing for the Indian national team.

Baliawas village is home to nearly 100 cricket grounds, used by both professionals and amateurs for friendly matches. But it wasn’t always like this.

Fifteen years ago, Baliawas was like any other village near Gurugram, next to the oasis of development, but carrying on with agriculture to sustain itself. From organic farming that focussed on growing strawberries and roses, the village has shifted to renting grounds for various sports. It’s lucrative and everyone is cashing in on it.

“In the next four or five years, Baliawas could become the sporting hub of Gurugram. If the roads improve a little bit and connectivity becomes easier, there is great sporting potential,” says Vishal Uppal, who won the men’s doubles bronze with Mustafa Ghouse at the 2002 Davis Cup. He now runs ‘The Tennis Project’ academy.

Also read: Golf is the new LinkedIn of NCR—networking, jobs and upward mobility

Land of both excellence and amateurs

It is not just teenagers like Sameer who turn up at Baliawas’ many sporting grounds. Corporate executives past their age of making it big professionally land up in the village to play their favourite sport.

Some have been doing it for more than 12 years, and it is now a part of their weekend routine. “I have been coming here for about five years. We have a WhatsApp group where we announce the match and book a slot accordingly,” says Tarun Bansal, a marketing consultant based in Gurugram.

Many have changed jobs and houses, but their passion for cricket, or any other sport they play, brings them to the village every weekend.

One can book a slot for a day-long cricket match for Rs 10,000. Some places add tea and snacks in the package. At the Skyline Golf driving range, one session costs Rs 700.

Also read: Noida vs Gurugram race is heating up. All eyes on Chautala’s job quota and Yogi’s Jewar

Strawberries and roses to school and sport

Baliawas’ development is synonymous with the establishment of the premier educational institute, Pathways School, in 2010. The school got the road built for the entire village stretch and also helped with the drainage system, street lights and even CCTV cameras, according to Capt. Rohit Sen Bajaj, the director of the school. “The residents of the village have been employed as part of support functions including security, housekeeping, nannies, drivers, conductors and catering service staff,” he said.

The school authorities also adopted three government schools in Baliawas and neighbouring villages. While students of Pathways do not necessarily play in the grounds outside, the school’s existence has turned out to be a boon for the village that now hosts football and tennis tournaments at district and national levels.

“Since villagers realised that they can earn more by renting out grounds, and agriculture or farming was not giving that, they also shifted their occupation,” says Geet Wadhwa, co-founder of Skyline Golf.

Along with Pathways, TERI, too, with its own cricket ground, has played an important role in Baliawas’ journey of transformation.

Also read: Gurugram is finally getting what it lacked. A culture Renaissance of sorts

Lack of facilities, incentives

Haryana is known for producing some of the best athletes in the country — from track and field athlete Neeraj Chopra who won gold at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics to freestyle wrestlers Ravi Kumar Dahiya and Bajrang Punia, the silver and bronze medallists at the event. And yet, apart from Tau Devi Lal Stadium and Nehru Stadium, there are not many sports facilities in the state. The infrastructure still needs massive development and overhaul.

“After kids reach a certain age, most parents say they have studies as a backup plan for life. That way the main plan remains unfulfilled,” says Neeraj Jain, father of 12-year-old Naman. In India, Neeraj says, sports facilities are still available to a select few. “There is endless talent in smaller places, but they lack facilities.” He says that sports cannot develop unless all talents from all corners of India do not have access to facilities.

The Haryana government has not yet extended any form of financial help or incentive for the development of Baliawas village. A villager who rents out a sporting ground said that they are instead being harassed over converting the area into a commercial space, which would mean higher taxes.

It remains to be seen if we finally get to watch Sameer or Naman play for India. But sports enthusiasts and parents alike hope that the government would take initiatives to develop the village so that children coming here would not have to give up their dreams of being sportspersons and choose ‘backup plans’ to study and get a 9-5 job instead.

(Edited by Prashant)