New Delhi: To the unacquainted, Central Delhi’s Mandi House might look like any one of the city’s arteries—part of a larger maze of traffic that keeps the city moving. But look closely, and it opens up, becoming as much a beating heart as it is an artery.

‘The Fifth Circle: Institution, Memory, Resistance’ initiative facilitates exactly that. Part of DAG’s ‘The City as a Museum’ festival, the audio walk and lecture reshaped Mandi House and rendered seemingly forgotten histories alive—be it aesthetic, architectural or cultural. The circle occupies a special place in Delhi’s cultural landscape. It’s carved from institutional memory but has been equally instrumental to building personal histories.

The DAG programme propels viewers to seek out their cities. For a couple of hours, Delhi stood transformed into a mosaic of memory far greater than the litany of problems today.

At the audio walk, a group of about 20 people were instructed to imagine the Mandi House of yore and recreate it through the eyes of theatre maker Amitesh Grover, who curated the Fifth Circle.

“My classroom, my mohalla, my stage, my refuge” is how Grover described Mandi House, which boasts of Delhi’s major cultural institutions, including the National School of Drama and the Triveni Kala Sangam.

But it was its public memory that was brought to the fore. While Mandi House was being dug up to build the metro station, traces of a colonial-era drainage system were found. For Grover, it served as another testament to the many secrets that it houses.

“Each strike of the machine was knocking at history’s closed doors,” he said, adding that it was not metro trains but processions that moved through these streets. “Is mobility the same as movement? Processions moved like a caravan of theatre and defiance. The artists’ unions and students still use Mandi House as a starting point. It stands at a threshold of unfinished marches and voices that refuse to leave.”

Walkers, listeners and movers were invited to peel off Mandi House’s layers and uncover its second skin. At the National School of Drama, Grover told them about the doyens of theatre who walked the very lawns on which they stood. They pictured Naseeruddin Shah performing ‘Waiting for Godot’, and Ebrahim Alkazi taking auditions in his peculiar way. But in reality, the lawn stood empty. Beside photographs of historic plays is a hoarding advertising Har Ghar Tiranga.

Also read: The many lives of Indian sadhus—rebels to arts to politics

Centre of politics, history & culture

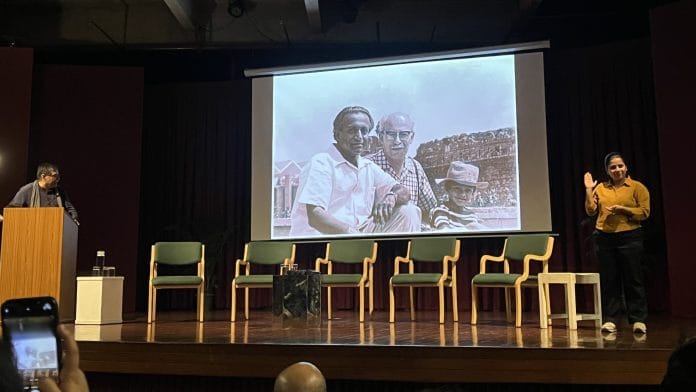

Mandi House was also situated in the city’s politics, history and culture through a seminar. Ram Rahman, Shukla Sawant, Zuleikha Chaudhuri and Sarovar Zaidi have had varying degrees of interaction with Mandi House. For Rahman, it’s inextricable from the personal—his father, Habib Rahman, was tasked with designing Rabindra Bhavan in the image of Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan by Jawaharlal Nehru himself. Meanwhile, Zaidi, a professor of architecture at OP Jindal University, brings her students to Triveni to interact with a different kind of cityscape.

“My father told Nehru that I’ve never done an institutional building with that kind of language. So Nehru had a direct input into what became Rabindra Bhavan. He ended up loving what happened with the building,” said Rahman, a photographer and a curator.

Housed between Rabindra Bhavan was a ruin; hence, the buildings are separate.

“As a child, I remember a remnant of mehrabs, sort of broken and plastered. There were remnants of a mosque in this kind of grove. And that grove was left untouched, separated with a sort of walkway,” Rahman added.

Meanwhile, Zaidi located Mandi House in the context of nation-building—a newly independent country which was searching for an identity. Mumbai had been cemented as the city of Bollywood. And so, Delhi became the city of theatre.

“Theatre and architecture get into a very interesting conversation. Different kinds of art and theatre spaces are commissioned,” said Zaidi. “In a sense, Central Delhi becomes the amphitheatre of performing the nation state that Nehru is projecting for the future.”

Moving from past to present, Zaidi also referred to one of her students, who is always sending her Mandi House tidbits—the samosawala at the roundabout, the swings which used to be at the back, and random spaces at Himachal Bhavan.

Vignettes like this make her wonder whether he is searching for places or for a time that has been lost?

The discussion eventually tapered into the contours of a seemingly changed Delhi—where Central Delhi is no longer seen as a cultural hub, in part due to the city’s rapid expansion. The tenor of the city has also been altered. Theatre and the arts are now mediated by privilege. Tickets are expensive, and trends have changed.

“There is a tone of lament in curating a programme around Mandi House. The lament comes from the acknowledgement of what has disappeared, what should have remained,” said Grover.

However, at the same time, the theatres are more packed than ever. Plays are being performed at Kamani, Shri Ram Centre, and LTG regularly.

“What’s interesting for me is to think about what is actually going on in Mandi House. One imagines that nothing happens at LTG, but there’s a huge amount of theatre,” said Zuleikha Chaudhuri, director of the Alkazi Theatre Archive. “It isn’t that this is a dead place. The whole circle is alive.”

DAG’s ‘City as a Museum’ festival ends on 21 September.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)