New Delhi: Before Independence, Indian journalists were all too familiar with sedition cases. But 18 years after the British left India, a journalist was arrested in Bihar for criticising then chief minister KB Sahay. The journalist, Thayil Jacob Sony George, became the first editor to be charged with sedition in an independent India.

George spent three weeks in Hazaribagh Central Jail, and former defence minister VK Krishna Menon rushed to Patna to defend him. The arrest was a mark of his courage and lifelong commitment to speaking truth to power.

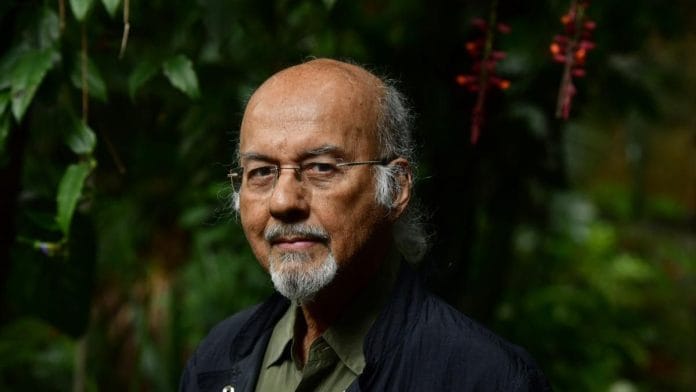

In his seven-decade-long career in journalism, George was a staunch advocate of press freedom, especially during the Emergency. He passed away at the age of 97 in Bengaluru on Friday.

On his demise, journalists, politicians, and public intellectuals remembered him for his courage and conviction.

“With his sharp pen and uncompromising voice, he enriched Indian journalism for over six decades. He was a true public intellectual who made readers think, question and engage,” wrote Siddaramaiah, chief minister of Karnataka on X.

“TJS George, an iconic figure in journalism whose pen was truly his sword,” wrote Rajdeep Sardesai, a senior journalist.

A man of dissent

Born in Kerala, he arrived in Mumbai in October 1947 with a degree in English literature. He applied to several newspapers, but only The Free Press Journal replied.

George went on to work with Searchlight, the International Press Institute, and the Far Eastern Economic Review before becoming the founding editor of Asiaweek. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 2011 for his contributions to literature and education.

“The saying goes that one has ink in their blood, for George, it was printing ink that coursed through his veins. He was not merely an editor, he was an institution—a beacon of intellectual courage, clarity of thought and unyielding conviction,” wrote AJ Philip, who worked under George.

During his association with The New Indian Express, George contributed 1,300 columns over 25 years before laying down his pen in 2022. His final column, titled Now is the time to say goodbye, reveals the core of his principles.

“Some of us feel that we should not criticise our own country. Some feel exactly the other way — that a big country like ours needs to be cautioned all the way about pitfalls. All arguments have their own supporters and their own critics, their own validities and their own drawbacks. But there is something not right if a country and its rulers start feeling that they should not be criticised at all — and especially by newspaperwallahs,” he wrote.

When praising governments and the leaders became a norm, George remained a man of dissent.

“TJS George was a legendary journalist and author who nurtured generations of journalists. Presenting truth based on facts mattered to him,” Anand Pradhan, author and professor at Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC), told ThePrint.

Pradhan said that his journalism philosophy was satta se sawal (questioning the powers that be). “He never hesitated to ask questions to the power. He came from the old-fashioned journalism school where facts mattered,” he said.

George authored several biographies, including Krishna Menon, M.S. Subbulakshmi: A Life in Music, and The Life and Times of Nargis.

Institutions mattered to him. The Asian College of Journalism was his vision, which started in The New Indian Express Bengaluru buildings.

He was a chronicler of independent India.

“TJS had a wide field of view and a narrow margin of error. He could admire a policy one week and expose its hollow core the next. He could be wry without being cruel,” wrote KM Seethi, director at Inter University Centre for Social Science Research and Extension, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kerala.

No one spared

According to BRP Bhaskar, few media persons have experienced the romance of journalism in as great a measure as TJS George has.

“He is a man who doesn’t mince his words to please others and who does not believe in withholding the truth however unpleasant it may be,” said K Javeed Nayeem.

In an article published a month before the 2019 election results, George criticised the Election Commission.

“The BJP uses India’s state machinery for party propaganda in ways that have never happened before and ignoring the fact that necessary evils, too, are evil. All that EC does is to go through the motions of action. Those who are asked to explain know that the EC is under the same compulsions as they are. This is an unfamiliar India becoming all too familiar,” wrote George in his article titled Necessary evils, too are evil.

When the Supreme Court freed all 32 accused in the Babri Masjid demolition case, George responded with stinging sarcasm. The only possibility, he wrote, is that the big Masjid fell down on its own. “Maybe the contractors used poor quality cement even in those days,” he added.

George went on to criticise the judiciary for its partisanship and endorsement of the Hindutva lobby’s stance that the Mughal period of history must be erased.

Even Prime Minister Narendra Modi is not spared by his pen. “There is something phenomenal about the way literature is building up on Narendra Modi. There is only one viewpoint that is presented in all these books: The greatness of Modiji as prime minister and as leader of people,” he wrote, adding that institutions like Parliament, the CBI, and Lokpal have become less meaningful in the Modi years.

George is gone, but he has left behind his words and his tools: courage, conviction, and unflinching, unsparing criticism.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

He ended up as a ten-a-penny, anti-Modi whining journalist since Modi came to power at the centre. I don’t remember him writing anything other than against Modi or the BJP.

First journalist to be charged for sedition in independent India by Bihar chief minister. Rest in peace