Of all the things that are unique to Hindi cinema, Manmohan Desai’s trademark confections are one. In his 33-year-long career, he made 21 films and most ended up as remarkable successes. Desai’s 25th death anniversary was observed this week.

In the 1970s, heroes had a certain set trajectory in every film, rising from the depths of poverty to make something of their life — what came to be understood as ‘formula’. No one perfected that commercial film formula better than Desai.

Roti‘s protagonist is Mangal. Born in abject poverty, the young boy loses his mother when he is unable to bring his mother ek roti — yes, literally one ‘roti’ could’ve saved her. She dies, leaving behind a son who turns to crime.

But Mangal is a criminal with a difference — unlike other bad guys, he is addicted not to alcohol or other intoxications, but ‘roti’. His relationship with ‘roti’ is complicated though. It doesn’t reach him easily. He always has to fight for it.

If you think all this doesn’t make sense, the rest of it won’t either.

Also read: Do Bigha Zamin, the Bimal Roy classic that Bollywood should look at now more than ever

Due to circumstances that are too convoluted to describe, including a midnight street duel over, well, ‘roti’, Mangal is sent to jail on murder charge. The opening credits roll and we hear (not see) a detailed argument in court over the importance of, again, ‘roti’ to a poor man.

Just before he is to be hanged, Mangal is rescued by his criminal benefactor in a helicopter action sequence that is to be seen to be believed.

In the next 10 minutes, he ends up committing another murder — that of a young man named Shravan — inside a train compartment.

Mangal escapes to a village in the mountains. There, on his hunt for, what else but roti, he reaches a house that later turns out to be Shravan’s. His parents turn out to be blind, waiting for their son to turn up.

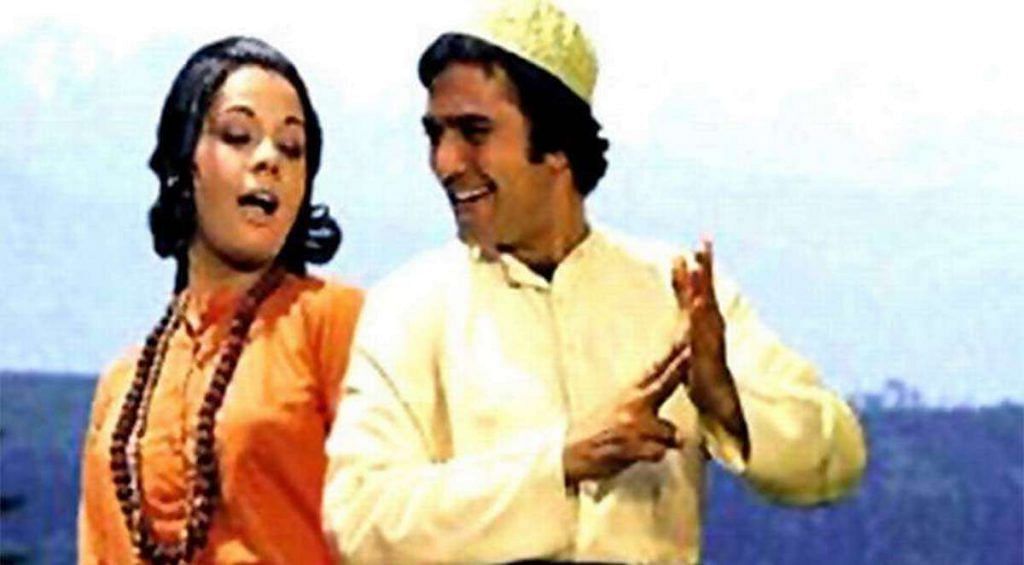

From here on, Mangal has a long way to trudge before earning redemption. On this path, he finds the romantic companionship of an orphan village girl, Bijli (Mumtaz), who is also self-made and street smart. He also ends up in a school teaching kids. And all this while escaping a police officer (Khanna’s ‘lucky mascot’ Sujit Kumar).

Also read: Namak Haraam, the film in which Amitabh Bachchan trumped then superstar Rajesh Khanna

Produced under Khanna’s own banner Aashirwad Pictures, the film had chartbusting music by Laxmikant Pyarelal and Anand Bakshi, including the popular ‘Gore Rang Pe Itna’ and ‘Ye Public Hai’.

Its story is a reworking of the legend of Shravan Kumar from ‘Ramayana’. Kumar was killed by King Dashratha and in repentance, he brings water to the killed man’s blind parents who curse him. It was that curse, as legend goes, that resulted in the exile for Lord Ram.

Hindi films have an unceasing connection to mythological stories. But in the hands of someone like Manmohan Desai, they turn out to be great entertainment.

Roti, like all Desai films, doesn’t have great pretensions about what it is — it is content in its space of being a popcorn entertainer with ‘masala’ and fun music. There isn’t the kind of craft to be admired that modern cinema lovers appreciate, but there is certainly a kind of craft that has completely evaporated from the Hindi film idiom — a desire for absurdities like a midnight duel over ‘roti’.

Also read: ‘Hindustan Ki Kasam’ reminds us not to caricature Pakistan

The climactic sequence of the film, on the road to redemption, leads to Badrinath where Mangal finds out that Shravan is alive. On seeing how Mangal took care of his parents, Shravan feels obliged to tell him that ‘sarhad’ is nearby. There is no explanation for why Mangal would seek asylum in China but these are not the questions for this film. Rotihits its melodramatic crescendo as Mangal and Bijli embark on a trip to China — there’s ‘maang’, there’s ‘sindoor’ and there’s a gunshot-induced avalanche. Desai even gets to make a point about giving people ‘do waqt ki roti’. But all this happens on screen in an almost auteuristic style.

Desai took this form to its pinnacle in his next release, Amar Akbar Anthony (1977). In that year, he had four different releases, all premised on the idea of lost-and-found.

Roti, however, exists in its space. And it’s quite certain that once you have seen it, you will never look at a ‘roti’ the same way again.