New Delhi: The opening scene of Real Kashmir Football Club has a young man cycling to a protest site outside a wine shop. Cries of “sharab haraam hai” fill the air. The young man then throws a grenade, triggering panic. But it is a fake grenade. The tension eases into laughter. The scene evokes conflict but swiftly shifts to mundane.

OTT is revisiting Kashmir, with makers focusing beyond the binaries of conflict and tourism. They are now adding layers to their stories without negating the trauma of an average Kashmiri — from Amazon Prime Video’s Songs of Paradise to SonyLIV’s Real Kashmir Football Club. Netflix’s Baramulla and Dibakar Banerjee’s shelved film Tees have pushed boundaries, mixing genres and putting ear to the ground to bring out a world and its stories that have been buried deep under mounds of stereotypes.

“What you see, be it in Songs of Paradise or Real Kashmir Football Club, is that it’s not just conflict. Even within conflict, people have dreams and aspirations, and while life gets affected by curfews, bandhs and other things, they dare to dream,” said filmmaker Danish Renzu, who directed Songs of Paradise and is one of the writers of Real Kashmir Football Club.

OTT is now telling tales that often do not travel beyond the valley, resisting the urge to fall into the stereotype. Real Kashmir Football Club is inspired by businessman Sandeep Chattoo and journalist Shamim Meraj, the founders of the actual club. And Songs of Paradise tells us about Kashmir’s first female playback singer, Raj Begum.

The forgotten sport of the Valley

In Real Kashmir Football Club, the valley’s love for the game is juxtaposed with the people’s lingering pain. Characters navigate their personal struggles to show up for the community.

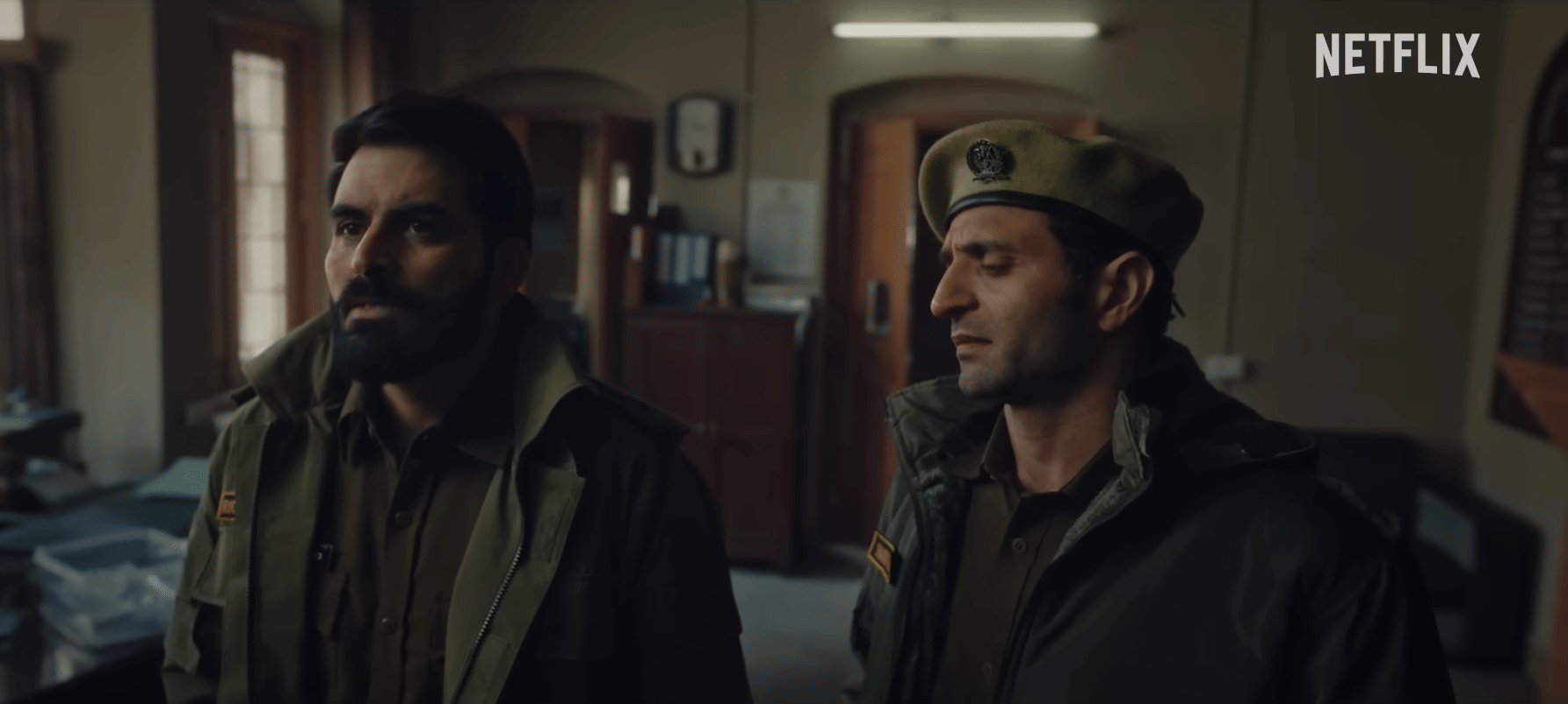

For Sohail (Mohammad Zeeshan Ayyub), a journalist disillusioned with his profession, football symbolises the good old days and the promise of a better future. He teams up with entrepreneur Shirish (Manav Kaul), a liquor supplier who returns to Kashmir after fleeing the Valley due to attacks on the Pandit community.

Back in the day, when the maharajas ruled Kashmir, football was a source of entertainment for the common people. After a hard day at work, they would gather, either to play or watch a match. But with the rise of militancy in the 1980s, football disappeared from public life.

Chattoo and Meraj brought it back.

Chattoo, a hotelier, and Meraj, editor of The Kashmir Monitor, started out with a community outreach programme, organising football matches after the devastating floods of 2014. It then turned into a professional club, as the matches became popular among both footballers and residents.

The club eventually became champions of the I-League 2nd Division, the third tier of the men’s football league, just two years after it was formed.

“It is incredible that I got to watch the two of them build this team. Chattoo used to say, this is my legacy,” said Arshad Shawl, director and owner of Real Kashmir FC. He joined the club in 2020, after Meraj decided to quit. A prominent advertising professional, Shawl took up the initiative to shine more spotlight on the club, along with bringing funds, sponsorships for securing the future of Real Kashmir FC.

“Kashmir has had a legacy of football. At one point, we had 19 international players from the state,” said Shawl.

The biggest achievement of the show has been in not letting slow motion, close-up shots of the players overshadow the storyline. Instead, it shows their everyday struggles to get to the field and play. Wearing bibs with motifs of chinar leaves and paisley pattern, the youngsters play in a ground next to a scrapyard, refusing to let local politics, militarisation, and even strict parents mar their dreams.

Also read: Anupama Chopra to Sucharita Tyagi—Dhurandhar critics face abuse. FCG is calling it out

Trauma and politics

The Kashmir Files (2022) dealt with the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. But Vivek Agnihotri’s storytelling was accused of carrying heavy biases, twisting facts. The controversy overpowered the subject itself. Even Aditya Dhar’s Article 370 (2024) chose to show that the abrogation of Article 370 was a win-win situation, at the cost of blurring facts and adding a figment of imagination. Vishal Bhardwaj’s 2014 film Haider, too, looked at the peak of militancy in Kashmir, but without using histrionics to attract cinema goers.

“I think the most interesting part for me is that a Kashmiri Muslim and a Pandit came together to create a team, which is a huge highlight especially because what we usually see is divisiveness. Our generation has only seen terror, and now we are also talking of peace, prosperity, community building,” said Renzu.

This does not mean that the show only focuses on sunshine and rainbows.

When Shirish visits the house in Pampore that his parents had to abandon in the 90s, he gets a panic attack. However, he doesn’t speak ill of or direct his hatred toward Kashmiri Muslims. All he wants to do is use this pain to build a future for future generations so that they do not suffer.

“The doors to the new stories are rusty, but they are finding their way,” said Manav Kaul, who played a Kashmiri Muslim cop in Baramulla.

“I have vivid memories of my father spending hours on the phone, discussing football with his friends. If anyone heard him, no one would imagine atrocities might have happened to Kashmiri Pandits,” added Kaul.

In Baramulla, a Kashmiri Pandit family murdered by militants gets justice through a Kashmiri Muslim family. In tone, however, it aligns with the previous depictions of the exodus, showing Muslims of the Valley in a bad light.

What Baramulla manages to achieve, and what Real Kashmir Football Club does better, is addressing the trauma of being a Kashmiri Pandit, which lingers across generations.

In Real Kashmir Football Club, the politics is not in your face but delivered in a nuanced, ingenious manner. A Scottish coach, Douglas (Mark Bennington), becomes the outside lens witnessing both the heavy military presence and the warmth of Kashmir’s people. When a match is to be played in the cantonment area, the players’ dilemma is a reference to the decades of atrocities that common Kashmiris have been subjected to at the hands of security forces.

Simaab Hashmi, who took multiple trips to Kashmir over a period of six years to write the script, had hundreds of conversations with local traders and footballers, listening to their stories.

But when he pitched his story, he found himself facing the familiar stereotypes. “Someone even said there isn’t masala, that is usually there in a story from Kashmir. I had to tell him–that is exactly what I am not trying to do,” said Hashmi.

The women of Kashmir

The newer OTT stories are also acknowledging the independence of the women. Another departure from the mould of the past.

Tees touches upon the friendship between Kashmiri Pandit Usha (Divya Dutta) and a Kashmiri Muslim, Ayesha (Manisha Koirala). Ayesha reaches out to her childhood friend Usha to solicit help from her husband — a government official — for her own husband, Ghulam Muhammad (Neeraj Kabi), who faces bankruptcy and ruin amid rising unrest in the city.

Ayesha is a state radio newsreader in the 80s. Her character exposes the audiences to the reality that women of Kashmir have actively participated in the public space.

Raj Begum, the focus of Songs of Paradise, was the first woman singer to perform on Radio Kashmir. Born in a poor, conservative family, she was married very early to a businessman. Begum never went to school, could not read or write, and had no training in music. But she would often sing at weddings across communities to help her family.

Eventually, she became the voice who would sing Gulrez (Scattered Flowers), a love story translated from Persian by eminent Kashmiri poet Maqbool Shah Kralawari, and Mashravthas Janan (My love, you’ve forgotten me), a poem by Kashmiri poet Rasa Javidani.

As political unrest escalated in the 70s and 80s, Raj Begum’s regular radio broadcast was the only routine that survived.

In Real Kashmir Football Club, too, women are employed in a variety of jobs — Dilshad’s sister Sameena works at a school, Sohail’s wife Ghazal (Priya Chauhan) has her own boutique, where Roohi (Sarah Gesawat), the young college girlfriend of Farooq, is also employed, and Nikhat is a journalist in Sohail’s previous office and reports on the club and its impact on the local community. There is also Shirish’s wife Kaveri (Vishakha Singh), a psychologist who runs a collective where women work together, sharing their stories, undertaking therapy, and even encouraging the men in their lives to try it. It is the women who hold the fort, literally, as the men find their place in the world, but without giving up their own pursuits.

“The most important revelation was getting to know of the women in Kashmiri, running business, driving cars with modified wheels for better movement in snow, just being a huge part of socio-cultural and economic spaces,” said Hashmi.

Sameena even decides to not marry, because her fiance does not stand up to his father who is against her working after marriage. She challenges his authority to decide her career for her, dismantling the idea that husbands have the right to give ‘permission’ to their wives to work.

Also read: Prada is making Kolhapuris cool. Limited-edition $930 sandals will roll out in February 2026

A revival

The stories from Kashmir and their screen adaptations have had real-life impact too.

Raj Begum’s journey paved the way for a slew of female singers who came after her, including Naseem Akhtar, Shamima Dev Azad, Asha Kaul, and Neerja Pandit. Songs of paradise opened doors for the lead singer Masrat Un Nisa, who became an overnight sensation.

“This is the revival of Kashmiri culture, and music is an important part of it. We are trying to tell stories of Kashmir through music and giving a platform to artists from the state,” said Renzu, whose music label, Renzu Music, was launched in 2024.

This movement of showcasing Kashmir through a motley of narratives is also happening through social media. Young Kashmiri Pandits living across the country are reviving customs, rituals, and food where even dehjoors — earrings worn by married women from the community — finds mention.

For Renzu, there are other areas of Kashmir that filmmakers can focus on.

“Kashmiri poetry needs to be celebrated, with works of Habba Khatoon and Lal Ded. The image of Kashmir in movies needs to change, and even the media should focus on how the people can be empowered, and given better opportunities,” said Renzu.

“I feel like this new wave of stories celebrates not just the struggles but also the success stories. Kashmiri culture and tradition has been lost in years of conflict,” he added.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)