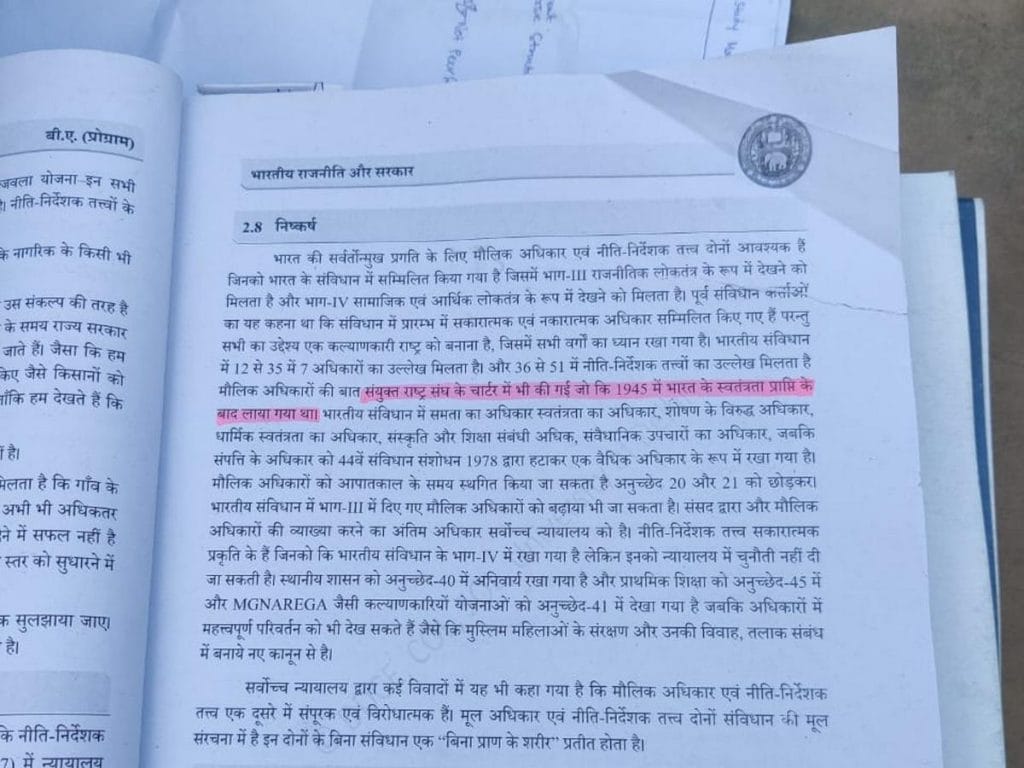

New Delhi: When 20-year-old Mohammad Aquib opened his School of Open Learning textbook and read that India gained independence in 1945, the Constitution was drafted in 1994, and Swami Vivekananda was “unprincipled”, he was stunned.

He and other students at SOL, the distance learning wing of Delhi University, tried to file a complaint at the end of 2023, during his second semester. They were shunted from one office to another, met with empty promises, and Aquib ended up back in his rented Wazirabad flat with the same error-riddled textbook.

“We’ve already fallen behind from students that are enrolled in regular mode. If we want to move ahead, we can’t—even the basics aren’t equal. All we have is education, and even that is full of mistakes. No teachers, no accurate study material, and when we try to complain, no one listens,” said Aquib, a Political Science student.

From a farming family in Balrampur, Uttar Pradesh, he lost his father during the COVID pandemic and is now supported by his uncle as he studies for both his degree and the UPSC exams. To him, it’s a “cruel joke” that the study materials already put him at a disadvantage.

History and other facts are being freely revised at Delhi University’s SOL. Nehru dies in 1967. The defunct Planning Commission is still chaired by the Prime Minister. It’s claimed Article 45 makes free and compulsory education a legal right, even though it’s only a directive principle.

At the Delhi University Academic Council (AC) meeting in May, members raised alarms about plagiarism, factual errors, poor grammar, and inadequate review in study materials. Despite repeated objections in earlier AC and Executive Council meetings, substandard Self Learning Materials (SLMs) were still being circulated and forwarded for approval without sufficient correction.

“A major procedural lapse is evident. Even by the May 2025 AC and EC meetings, SLMs for semesters I to VI were still being tabled—despite exams already being held. This means SOL students from the first to third year were evaluated using SLMs that hadn’t been officially approved, violating the UGC’s ODL (Open and Distance Learning) Regulations, 2020,” Maya John, Academic Council member and an assistant professor at Jesus and Mary College, told ThePrint.

SOL director Payal Mago, however, said that plagiarism and AI checks are in place and that corrective action is being taken.

“If mistakes are found in the SLM, I will blacklist external faculty so they never work with SOL again, and issue memos and inquiries for internal faculty,” she said.

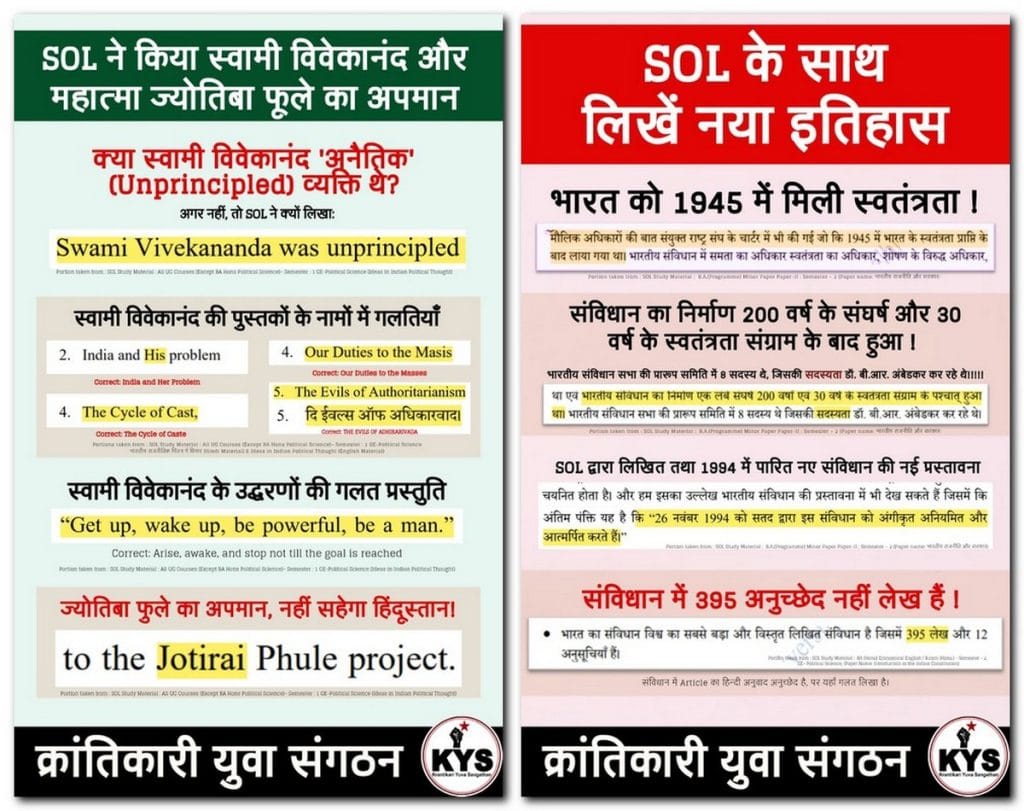

SOL has been under scrutiny since 2023, when DU’s Academic Council flagged glaring factual and typographical errors in its Political Science study materials. Formal dissent notes have subsequently documented the same problems in papers across History, English, Economics, and other subjects. Students and faculty claim the issue has plagued SOL for even longer.

A review committee formed in 2023 offered only basic content guidelines, without evaluating quality. Despite promises of stricter checks, flawed materials continue to circulate, in violation of UGC norms.

Most of the nearly five lakh SOL students come from low-income or marginalised backgrounds. With limited classes and little support, they rely on their printed study material. And their problems don’t end with shoddy textbooks. They are now demanding urgent transparency, accountability, and real quality control in distance education.

On 23 May, SOL students were forced to write their exams in a basement parking lot filled with construction waste, metal pipes, and toxic materials, endangering their safety. Videos shared by students showed ongoing construction at the site. The incident triggered a major protest by Krantikari Yuva Sangathan (KYS)—a student organisation of “working-class” SOL students. The protesters condemned DU and SOL for gross negligence and discrimination against marginalised students. They demanded an FIR under the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita against the responsible officials. Students also reported being uninformed about internal assessments, leading to ‘Absent’ or ‘ER’ (essential repeat) grades.

“A large number of students come to public universities because they can’t afford private ones. Many are working or disadvantaged, and they get to meet teachers in class on a few days—so if we waste those small windows of opportunity, we let them down completely,” said Anita Rampal, an educationist and a former Academic Council member. “DU must take this seriously and form a committee of committed people. Not those forced into it, but those who genuinely care and can motivate through their knowledge of the discipline, to ensure academic support, quality materials, and help where needed, including getting professional proofreaders.”

Also Read: Delhi student politics is changing. New DUSU president’s use of fear and force has many fans

Copy-paste, ‘Mountain Dew Chelmsford Report’

Many of SOL’s Self Learning Materials read like a rushed copy-paste job. A detailed review conducted by John and KYS members, seen by ThePrint, shows entire paragraphs lifted from IGNOU course materials, Wikipedia, news outlets like The Statesman, and websites such as GK Scientist. There are no citations in sight.

Worse, these materials are still prescribed despite having been flagged in previous EC and AC meetings. In the BA (Hons) English DSC-12 paper, Indian Writing in English Translation, a section titled ‘Tagore’s Idea of God’ has been copied verbatim from online sources. This and similar examples were raised in AC meetings both in 2024 and on 10 May this year, with no corrections yet.

In another glaring instance, Chapter 6 of Cultural Transformations in Early Modern Europe – II was plagiarised from a paper authored by B Dahiya, an undergraduate from St. Stephen’s College, batch of 2022. The material falsely presented her as a renowned scholar. This same error was flagged in 2024. Yet, it remained in the paper and was brought up again in the 2025 AC meeting, said Prithviraj, a member of KYS.

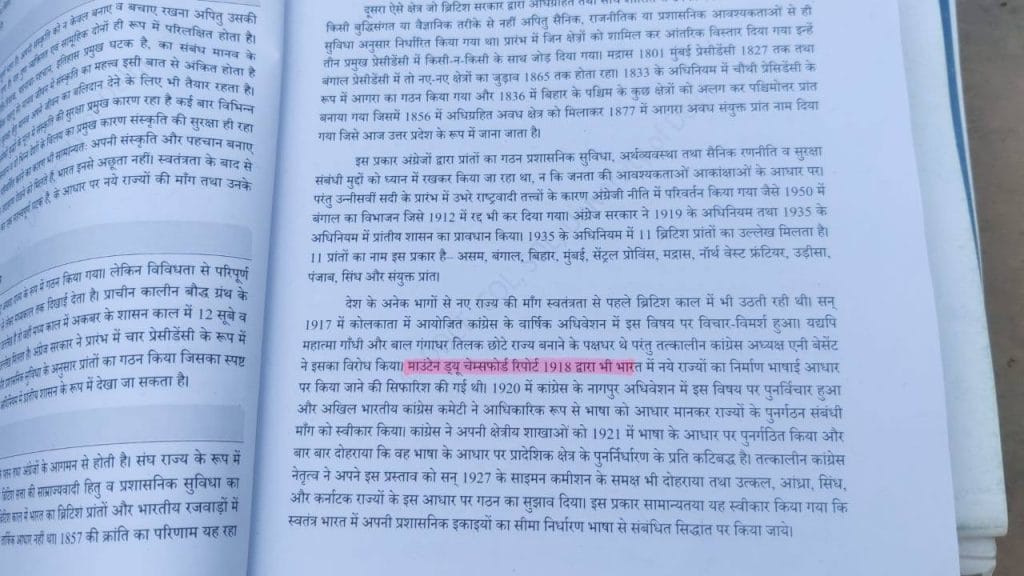

Names and historical facts are repeatedly distorted as well. Former British PM Ramsay MacDonald appears as “Ramsay McDonald”. Subhas Chandra Bose becomes “Subash Chandra Boss”. Historian Bipan Chandra turns into “Vipin Chandra”. The political party Asom Gana Parishad is misspelled as “Assam Gun Parishad,” and “East India Company” bizarrely becomes “Healthy Company.” The “Montague-Chelmsford Report” is rendered as “Mountain Dew Chelmsford Report”.

“Most of these students are first-generation learners who haven’t studied this material in detail. Many encounter these topics for the first time, and the inadequate, error-filled study material only adds to their confusion,” said Prithviraj.

At the 12 July 2024 Academic Council meeting, peer-reviewed texts were also found to contain leftover notes like “not very clear”. Confusing contradictions are left unchecked for students to grapple with—the Constitution, for example, is described as being drafted in both “2 years, 11 months, and 17 days” and “18 days”, depending on which chapter you read.

The errors don’t stop at names or timelines. Experiments are attributed to scientist and philosopher William Gilbert in 1544, his birth year. The Odia poet Brajanath Badajena is said to have died in the year 17,995. Aufklärung, the German term for the Enlightenment, is mistakenly introduced as the name of a philosopher.

“It is being said that there is a Constitutional Monarchy in India in the paper of Western Political Philosophy. Which king’s daughter is Droupadi Murmu?” asked Prithviraj.

There is also a disparity between the English and Hindi versions of the same study materials. While the English versions are plagiarised from multiple sources, the Hindi versions often skip key topics altogether, such as Indian Oceanic Trade.

KYS first formally raised such concerns on 1 November 2023 through a memorandum to the SOL Principal. It cited delays in material distribution and content marred with plagiarism, factual inaccuracies, confusing language, thus going against UGC’s 2017 and 2020 guidelines.

They followed up with a memorandum to then UGC chairperson M Jagadesh Kumar on 11 December 2023, accusing SOL of mismanagement, corruption, and using unreviewed NEP-UGCF content as official study material. A year later, on 12 November 2024, they sent another appeal to the principal of SOL, flagging unresolved issues, including missing study material, incomplete Personal Contact Programme (PCP) classes, and poor communication leaving lakhs of disadvantaged students at risk of academic failure.

How SOL fell behind

When SOL was first established in 1962, it worked closely with university departments. Subject experts reviewed and approved every course. But this coordination eroded over time, especially after 1997, when SOL stopped receiving central funding.

The rollout of the National Education Policy (NEP) and the Undergraduate Curriculum Framework (UGCF) only widened the gap between SOL and university departments. Academic units were excluded from the process of designing course materials, and SOL faculty began producing content without input from subject experts.

Unqualified staff were tasked with writing content outside their areas of expertise and that too within unrealistic deadlines.

“Someone [with expertise in] Medieval India, for instance, was developing material for Modern India,” said a DU professor previously involved in SOL’s peer-review process, asking not to be named. “And the timeline was equally alarming: entire booklets of 400–500 pages were expected to be completed in just 15 days. It is humanly and pedagogically not possible.”

Rigorous peer review fell away and feedback was often ignored. Some suspect that AI tools or Google Translate were used in place of scholarly research, said a DU professor, asking not to be named.

The situation worsened in 2019, when the university abruptly introduced semester-based instead of annual exams at SOL without adequate preparation or updated materials.

While DU’s regular courses switched to semesters in 2011 and revised syllabi under the Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) in 2015, SOL stuck to the outdated pre-2011 syllabus until 2019, said Academic Council member John.

“SOL lagged far behind with no meaningful updates,” she added.

The sudden shift triggered protests, with students holding a mock funeral for the Vice-Chancellor and sending shaved hair to officials. After a student petition, the Delhi High Court directed SOL to improve its infrastructure but did not stay CBCS. Instead, it ordered both semester exams under CBCS to be held one after the other, effectively making it an annual mode of examination.

“When students from SOL study, they often do so without teachers, classrooms, or reliable guidance. Relying solely on flawed study material, with no time or resources to verify it, creates a distorted education filter that disorients these vulnerable groups,” said the DU professor quoted earlier.

Repeated red flags and ‘rubber stamps’

When SOL students like Mohammad Aquib spotted glaring mistakes in their textbooks, they flagged them to the Krantikari Yuva Sangathan, which passed them to Academic Council member Maya John. She raised the issue at the 11 August 2023 AC meeting.

There, members questioned how SOL’s study materials were being written, who was picking the writers, and whether anyone was actually reviewing the content.

“There is a huge lack of transparency, with much of the work being outsourced or poorly overseen,” said John. This is despite UGC’s Open and Distance Learning Regulations requiring that up to 60 per cent of the material be produced by the institution’s own faculty.

Nearly two years since that August 2023 meeting, not much has changed. At the 23 May 2025 Executive Council meeting, member Aman Kumar slammed the university for tabling subpar SLMs for approval after the UGCF rollout—when they should have been finalised before students even began.

“As per section II (A) of Annexure VII in the University Grants Commission (Open and Distance Learning Programs and Online Programs) Regulation, 2020, in the case of Under Graduate Programmes (3 years duration), SLM should be ready in all respect for the first two years and its approval by the statutory authorities of the Higher Educational Institution. However, SLM is being tabled for approval after the commencement of the UGCF in SOL, and that too of poor quality which reflects severe lack of preparedness,” read his dissent note.

Kumar pointed out in his note that despite a review committee being set up in November 2023, no report was submitted and flagged materials continued to circulate unrevised, including some Semester I to VI papers being re-tabled despite earlier concerns.

“You provided the study material, conducted the exams, completed the semester, and only afterward did you bring the material for approval. It’s like a rubber stamp—essentially just passing everything without proper scrutiny,” said John.

She expressed deep frustration over the lack of transparency in content creation and review. “There is no process where somebody goes through all the material of that paper. There is no actual review process. The people who are writing the book, they cannot be the peer reviewers. In most cases, they give each other their papers for review.”

The AC recommended an immediate impartial audit of SOL, withdrawal of the current SLM from approval, and a thorough review of all SLM submitted since 2022. It also directed SLMs should not be shared with students until all issues are fixed.

Payal Mago, director of SOL, told ThePrint that the issue was being handled rigorously.

“Blacklisting and reviews have already been implemented, and promotions of several people have been stopped until they apologise and withdraw the incorrect material,” she said.

Mago recalled a case where a faculty member mistakenly wrote that India got independence in 1945, and his promotion was halted for a year until he apologised.

“SOL responded to both the PMO and LG. What more can we do?” she said.

Also Read: Over 60 actors rejected the lead role in this film. It’s about the ‘lies’ in school textbooks

Few resources, ‘no respect’

What should have been a straightforward exam turned into a nightmare for Aditya, a 20-year-old Political Science student at SOL.

Last December, when the Ghaziabad resident arrived at his exam centre to write his third-semester Political Analysis paper, the security guard asked him to re-download his admit card. Inexplicably, the subject had been changed to English. With no other option, he sat for the wrong exam— only to later discover he’d been marked absent for the right one. He’s since submitted multiple applications and paid Rs 420 to retake the paper, but the error still hasn’t been corrected.

Aditya says his overall experience at SOL has been far from edifying. When he informed a teacher that one book wrongly stated Gandhi returned to India in 1916, he essentially got a shrug as response.

“The teacher said, ‘This is SOL’s fault. If you know the correct facts, study accordingly. We just follow the syllabus’,” he recalled. Teachers, he added, often seem unmotivated: “They don’t even know the material. They write SOL content half-asleep.”

The very infrastructure and resources available to SOL students also fall woefully short. For nearly two lakh undergraduate students, only 30,000 copies of the political science General Elective study paper are printed, leaving many floundering.

Open and Distance Learning regulations mandate delivery of materials within 15 days of admission, but the rule is not always followed.

For the ongoing fourth semester, Aditya has seven subjects but received materials for only five. Others got none.

“Though the semester began in February, my books arrived only on 21 March. I have a Financial Literacy exam on 10 June but still haven’t received the study material,” he said.

The physical facilities are equally bleak. The PCP programme, intended to support students through 10-15 in-person classes at study centres, barely functions.

“They are not even sending the SMS to many students for these classes,” John said, adding that some colleges barely held a handful of classes.

According to Prithviraj, there are only about 100-150 classrooms available for all SOL students. And many are struggling academically.

“There was no basic knowledge—no understanding of the world map, no sense of timelines. Students didn’t know the difference between AD and BC, or CE and BCE. I asked a third-year student how far back 500 BC is, and he said 1500 years. He didn’t know that 500 BC meant 2500 years ago. For him, BC and AD were the same,” said a PhD scholar, who taught SOL students as a guest faculty.

These academic issues are made worse by the daily hardships SOL students face on campus. They claim they are subjected to discrimination and barred from sitting on the grounds. Disabled students face even harsher conditions. Lifts frequently break down, washrooms are inaccessible and unclean, and wheelchairs are often denied.

“We are left to fend for ourselves with no support, no space, no materials, and no respect,” said Prithviraj. “We want a comprehensive, impartial academic and administrative audit of SOL.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)